Each week, we take a look at our archives for boosts to propel you into the weekend.

In January 1992, Frances Fox Piven and Barbara Ehrenreich sat in on a forum hosted by the Nation to hear Jerry Brown—then running for the Democratic presidential nomination against third-way Democrat Bill Clinton. “Strikingly,” Ehrenreich noted in her essay for us on that campaign, “he was talking about class.” Piven and Ehrenreich nudged each other, raised eyebrows, and watched as “nearly five hundred hard-nosed New York leftists clapped till their hands were calloused.”

It’s a tiny moment. But I spoke to Piven for an article earlier this year, and Ehrenreich is a hero—so it is one of those small, fascinating, and accidental scenes that gives one a jolt. Whoa! They’re friends! I’ve found that happening often in the archives, especially in the 1990s and 2000s. You recognize the names (Gingrich, Clinton, Trump), but they come up in different contexts. I was speaking recently to a friend about how these decades almost feel further away. The fall of the utopian ’60s to the overdrive ’80s consumerism is well-trod territory; I can chat about the 1930s and 1940s with any white man over the age of 60, as it is law they must be obsessed with either World War II or socialism. But chatter about the Iraq War and Clinton’s business-friendly Democratic Party is relegated to broader strokes. (That’s my narrow experience, at least.)

Reading Ehrenreich’s larger analysis of the 1992 campaign, I was surprised by the details; I was surprised to see her framing of Clinton’s rise generally. The press loved his white male fighting spirit, she writes. They enjoyed the gladiatorial nature of his quest. It was, she felt though, almost meaningless. It was a PR stunt and a sideshow. She remembers George H. W. Bush canceling a trip to Brazil on government business because he was too busy running for reelection. And it dawned on her: “Today, being president is really no different from running for president.”

That sounds almost trite. But whereas we may fix that to political jostling or reality TV or 24-hour news, Ehrenreich has, I think, a better explanation.

She notes there is no “tangible product” for many when they look at the government. We are glimpsing, in the constant election cycle, “that emptiness at the center of things.” The business of government has been completely subsumed by the act of electioneering because the business of government is, well, gone: erased by Reagan and then adopted by Democrats.

“It is government-as-spectacle,” she writes, “and much of it has been a sorry spectacle indeed.” Before, “words like ‘policy’ and ‘programs’ meant something even to ordinary people, of the kind who do not reside in think tanks.” Think of “Medicare, Medicaid, Title VII, Title IX, OEO, OSHA…”

If you’re looking for the start of the never-ending campaign, she posits, why not locate it in when the government stopped having anything else to do. Ehrenreich, in those early days, did see hope in the Brown campaign: a smattering of burnout kids, workers, union nurses, and Allen Ginsberg.

She decided to root for him when she saw Brown joust with Clinton in a debate, and upon being prodded on how his health care plan would have the audacity to harm the bottom line of rich doctors, Brown said, with a grin, “I can’t wait.”

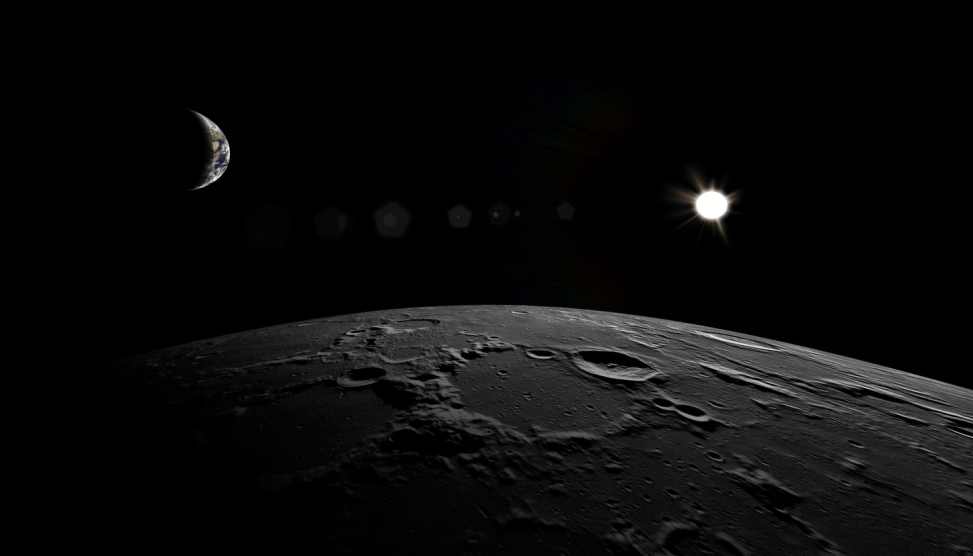

The longtime California politician is an odd figure. The son of a previous governor, prone to late-night working, and a figure associated with the 1960s left despite being in Yale Law School at the time; his penchant for a certain spirituality (he was called Gov. Moonbeam, famously), and also for strict Catholic rules, caught many off guard. Gary Wills in a 1976 essay for the New York Review of Books compared him to Thoreau (unfavorably!).

In vying for Brown, Ehrenreich predicted the new leftist turn a bit too early. She thought Brown’s ideas were simmering into a Democratic party less interested in cutting and gutting and more invested in a class-based approach. It didn’t happen in the 1990s. But it might be happening now. (Might, I stress.) For all the vapidity of the constant electioneering, policies and programs do matter to people again: Medicaid, the Affordable Care Act, Social Security.

I could be falling into the same hopeful trap here too.

Ehrenreich ends on the right beat. We just don’t know:

But the other great lesson of the last calendar year is: You never know. What began in a frenzy of jingoism ended in bitterness and economic collapse. Today’s defeat may be tomorrow’s opportunity, and opportunities evaporate even as they come into view. There is a wild churning force at work in our media-driven culture, driving us from “crisis” to “crisis,” from one mad, collective mood swing on to the next. Those who would win must learn how to ride along with this force, disdaining defeat, grasping every favorable current and eddy, trying and trying, getting the joke. There will be a next time, and this we know for sure: Next time is bound to be different.