Jacopo Landi/NurPhoto/AP

Minnesota teenager Ava T. lives with seizures that predominate in the morning, preventing her from attending school safely before noon. When her suburban Minneapolis school district refused to update her individualized education plan—a disability accommodation guaranteed by federal law—to allow at-home evening instruction to compensate, Ava and her parents sued in 2021.

A district court sided with Ava and her family—her last name is withheld—ruling in 2022 that the school district had violated her rights under the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act. But separate complaints say that the district had breached Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and the Americans with Disabilities Act, which include extensive disability rights provisions. In five of the 13 federal circuit courts, including the Eighth Circuit, which covers Minnesota, families suing schools under Section 504 and the ADA have to prove “bad faith or gross misjudgment,” a standard the Eighth Circuit said Ava’s case did not meet—despite acknowledging that the family “may have established a genuine dispute about whether the district was negligent or even deliberately indifferent.”

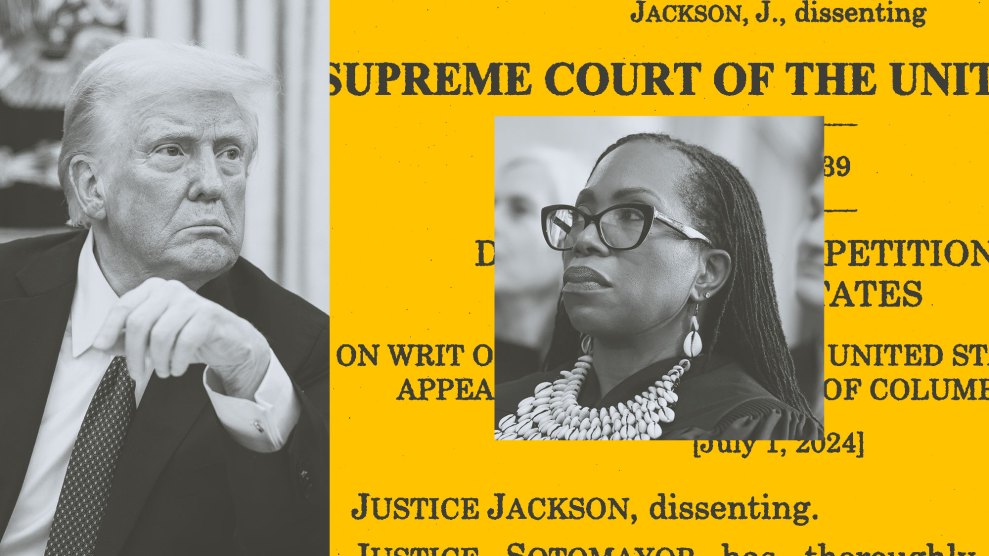

The Supreme Court agreed to hear Ava’s case, A.J.T. v. Osseo Area Schools, in January. Its ruling will decide whether that tougher standard—bad faith is notoriously hard to prove—applies nationwide under Section 504 and the ADA when suing schools. A ruling against Ava and her family could be a major setback for student disability rights enforcement and an equally major boon for the Trump administration’s plan to gut the Department of Education at the expense of disabled kids.

“All that [Ava] was seeking was the same kind of access to an education that she would have had if she didn’t have this disability.”

“Bad faith and gross misjudgment are kind of a made-up standard that’s not in the text of the statute at all,” says Stanford Law School professor William Koski, who directs the school’s Youth and Education Law Project. If the majority of justices were—as they claim—”textualists,” Koski says, they’d overturn the Eighth Circuit’s ruling.

The Osseo case has drawn less public response from disability organizations than other suits to reach the Supreme Court—like 2023’s Acheson Hotels, LLC v. Laufer, ruled moot before it was heard—perhaps because of more drastic, faster-moving concerns, like executive branch assaults on the Department of Education and vital medical research. Unlike some of those attacks, this case wouldn’t risk a wholesale dismantling of disability rights, but rather continue to expand an anti–civil rights practice not rooted in law.

Koski sees it as positive “that the court’s going to weigh in” on the contested topic, but “as a lawyer who represents children and families,” he says, “I hope they clear it up on the side of the less stringent standard.”

The Council of Parent Attorneys and Advocates, an association of disability advocates, parents, and lawyers—submitted a statement in support of Ava T.’s case. “All that [Ava] was seeking was the same kind of access to an education that she would have had if she didn’t have this disability,” COPAA legal director Selene Almazan told Mother Jones. Almazan says the bad-faith test is at odds with the Handicapped Children’s Protection Act of 1986 that was codified into law by Congress, calling the test “a very outdated standard”—one that the Supreme Court might even overturn.

The school district in the case, meanwhile, has repeatedly argued that a ruling in its favor would have little impact on kids with disabilities. Koski, who has a long history of litigation in support of disabled children and their families, disagrees.

“If you have a more stringent standard like bad faith or gross misjudgment,” Koski says, “It’s going to be much more difficult for plaintiffs to bring freestanding, independent claims under Section 504.”