Gates that separate the Cuban side from the Guantánamo Bay US Naval BaseRamon Espinosa/AP

In January, President Donald Trump signed an executive order to expand immigration detention space in Guantánamo Bay, Cuba, to “full capacity.” It was another salvo in Trump’s campaign of fear: the infamous American detainment compound thrust forward as punishment for immigrants living in the United States. The administration started flying dozens of Venezuelans with alleged connections to gangs from El Paso, Texas, to the naval base—where a tent camp is under development to detain as many as 30,000 “high-priority” immigrants—last week.

Republican and Democratic presidential administrations have held refugees and asylum seekers intercepted at sea at Guantánamo going back decades. But this is the first time immigrants already on US soil are being kept there. Immigrants are not being detained in the Migrant Operations Center (MOC)—as has historically been the case for migrants—but in military installations reserved for suspected terrorists, according to reports. Department of Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, who visited Guantánamo Bay, didn’t rule out the possibility that immigrants could stay detained indefinitely.

“This is just another attempt by a sitting US president to weaponize the specter of Guantánamo.”

Many lawyers and advocates have been warning of the risk of sending thousands of immigrants to a “legal black hole” such as Guantánamo. “This is going to take a massive infusion of funds and personnel,” says Jessica Vosburgh, a senior staff attorney at the Center for Constitutional Rights, one of the organizations that recently petitioned a federal district court in New Mexico to block the transfer of three immigrants to Guantánamo—and won. “And there are huge concerns about [what] would result from such a scramble to create what would essentially be a giant open-air prison.”

The case was brought by the Center for Constitutional Rights, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) of New Mexico, and Las Americas Immigrant Advocacy Center on behalf of three Venezuelan nationals who the government has accused of having ties with the Tren de Aragua gang and who are currently detained in the Otero County Processing Center in Chaparral, New Mexico. I spoke with Vosburgh and her colleague Ayla Kadah about their legal victory and how the Trump administration is engaging in a “punitive theater”:

What information do you have about the immigrants currently being held at Guantánamo?

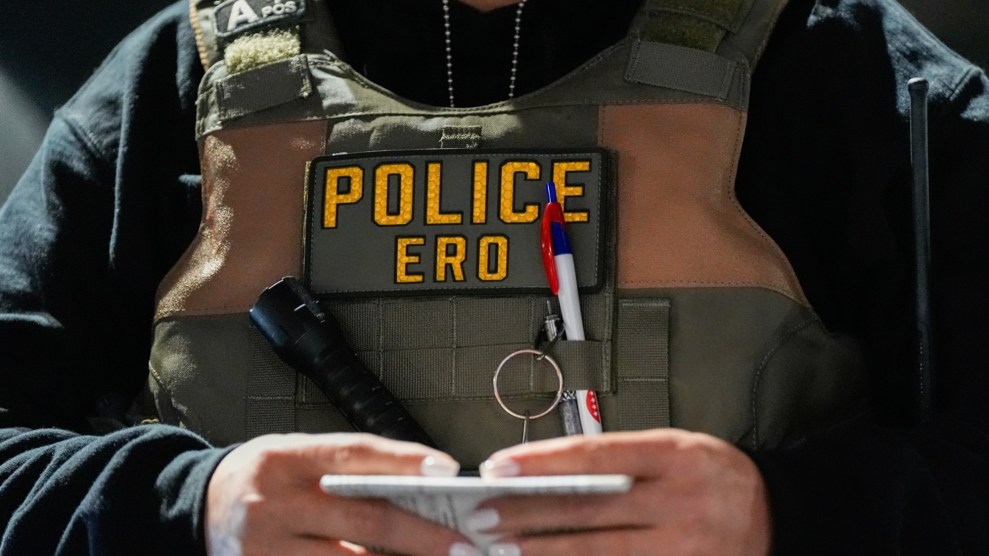

Kadah: We don’t know very much about the men that have been transferred so far. What we do know is that the Trump administration has stated its intention to prioritize the transfer of Venezuelan men with ties to the Tren de Aragua gang and with pending orders of removal. We’ve also been having issues trying to get additional information. ICE appears to be evasive, at best, lying, at worst, about where people are and not really updating their systems.

The lack of information speaks to the fact that there’s no transparency. The government is essentially disappearing people into what has historically served as a legal black hole—this offshore, remote detention facility that is notorious for human rights abuses and diminishing people’s legal rights.

From reports that we’ve heard, the transferees are currently being detained not in the civilian Migrant Operations Center (MOC) at Guantánamo that has historically been used to detain migrants interdicted at high sea. Instead, they’re being detained at Camp 6 in the military detention center, which is the same prison designed to house law-of-war detainees apprehended in post 9/11 operations.

What legal authority, if any, is the president claiming to allow him to transfer immigrants from the interior of the United States to Guantánamo and detain them in military facilities?

Kadah: Military detentions are authorized only under the 2001 Authorization for Use of Military Force (AUMF). So the fact that they’re using these military detention facilities for migrants is illegal, and we have deep concerns about the lack of due process and the risk of indefinite detention for transferred migrants. The AUMF only authorizes the use of “necessary and appropriate force” against specific groups connected to the 9/11 attacks, so the Taliban and Al-Qaeda and associated forces. It doesn’t authorize the military detention of migrants, people convicted of crimes, or anyone that’s just broadly designated as a terrorist or a member of a foreign terrorist organization.

Vosburgh: It is unprecedented what is reportedly occurring to transfer people in immigration custody on US soil to Guantánamo.

Earlier this week, a federal district court temporarily blocked the transfer of three of your clients, who are detained in New Mexico, to Guantánamo. Can you talk about that win and what happens next in the case?

Kadah: Our motion was limited to our three clients and essentially our argument was that there’s a complete lack of certainty about whether the court will be able to retain its jurisdiction over the case and whether our clients will be able to access their lawyers and have their legal rights—including the right to due process, the right to adequate conditions of confinement, and the right against unlawful detention. We were simply asking the court to maintain the status quo, keep our clients where they are, and stop the government from any potential transfer that they’re planning to Guantánamo until at least there is more certainty about what legal rights they would retain. We have been told by the government that our clients are not being presently moved to Guantánamo, but they provided no assurance that they would not be moved there in the near future.

We’re continuing to challenge the lawfulness of our clients’ detention through the pending habeas corpus case. That’s always been the goal of this case, which we filed back in September before any of this Guantánamo news became relevant. Our position remains that if the government is unable to deport our clients to Venezuela or a third country, they should just let them go. It’s been over a year of detention for our clients and, in the meantime, they’ve been languishing in custody, separated from their families, and with their health deteriorating. Our position remains that their continued indefinite detention is not acceptable and it’s not authorized by the law or the Constitution.

Your case is narrow in scope. Do you anticipate broader lawsuits challenging the transfer of migrants to Guantánamo?

Kadah: We expect more legal challenges. The hope is that others will follow suit and challenge those transfers, both on an individual and systemic level.

Do we know what the Trump administration will do with individuals who can’t easily be sent back to their home countries? How long will they remain detained?

Kadah: It’s unclear how their rights will be respected, whether they’ll be respected, and to what extent.

Vosburgh: The administration’s goal was to engage in this punitive theater of transferring them to Guantánamo. This isn’t part of some kind of logistics flight pattern plan. It was highly intentional to make a large media show. Something that legal advocates, migrants in detention, and the Trump administration all agree on is that Guantánamo is known the world around as a symbol of human rights abuses and a legal black hole.

Kadah: This is just another attempt by a sitting US president to weaponize the specter of Guantánamo and what it symbolizes to further demonize and discard a group of people and undermine their legal rights and basic humanity. We see this challenge as an important effort to interrupt that cycle, as many before us have done.