Louisiana is one of the few where there are no restrictions on when, where, and how often commissioners can communicate with the utilities they regulate. Louisiana Public Service Commission YouTube channel

This story was reported by Floodlight, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.

This past April, days before a Louisiana Public Service Commission (PSC) meeting at a remote lakefront resort, the state’s largest power company dropped a bombshell. Entergy asked the five commissioners to vote—four months ahead of a schedule—on an ambitious resilience plan slated to cost nearly $2 billion.

A Louisiana consumer watchdog group and the state’s refineries and chemical plants formally objected, saying the process was “unnecessarily fast-tracked” and that Entergy had provided “insufficient information” to evaluate the plan, which included replacing and strengthening utility poles and power lines and protecting substations from flooding.

Despite these objections, Entergy’s plan was added to the agenda. “This is [a] wholly undemocratic process,” James Hiatt, an environmental activist, protested to the panel. “Why does it need to be rushed through today?”

Shortly before the meeting, Entergy’s big industrial customers, including Chevron and ExxonMobil, dropped their opposition to the plan after the PSC shifted millions of dollars of the cost onto Entergy’s residential and commercial ratepayers.

Commissioners Davante Lewis and Foster Campbell, blindsided by the change, pushed their colleagues for a postponement. They were overruled, and the plan was approved.

Entergy Louisiana

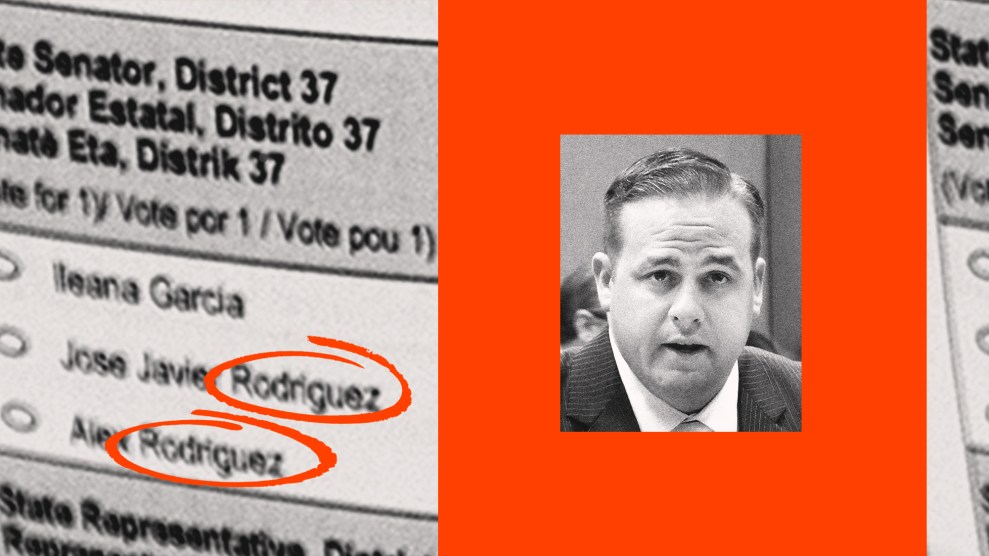

This last-minute decision to saddle ratepayers with a greater share of the utility’s costs, exemplifies the imbalance of power in Louisiana and what’s at stake in the upcoming election for an open PSC seat. Whoever wins will replace Republican Craig Greene, a critical swing vote on the commission.

“Most residents in Louisiana have no idea who’s making the decisions about how much their utility bills cost,” said Logan Atkinson Burke, executive director of the Louisiana-based consumer group Alliance for Affordable Energy. “You can’t possibly say residents have the same voice the fossil industry and utilities do.”

“I don’t know of another public service commission that has the level of authority and the breadth and depth of jurisdiction without…any other controls.”

One possible reason for the power imbalance: Over the past decade, nearly 43 percent, or about $3.5 million, of all $250-plus campaign donations to Louisiana’s commissioners came from utilities, energy-related businesses, and their attorneys and lobbyists, according to a new Floodlight analysis of elected utility commissioners in multiple states. “It’s probably as close to bribery as you could possibly get and call it legal,” said Simon Mahan, executive director of the Southern Renewable Energy Association.

The PSC, in turn, has resisted measures that could curb utility profits, such as requiring them to encourage energy efficiency or add renewable energy to the power mix—actions that could not only save ratepayers money, but also help reduce greenhouse gas emissions in one of the states most affected by climate change.

Beyond the campaign donations, Louisiana law lets its commissioners engage in unreported private chats with representatives of the utilities they regulate—”ex parte” communications that are banned or subject to strict reporting requirements in many other states. This can work both ways, said commissioner Lewis, who described such conversations as “very frequent and very deliberate.” He can reach out to the utilities to say he disagrees with their stance on certain issues, for example. But absent any restrictions, “I do think it is a little bit harmful to the people of Louisiana.”

According to David Cruthirds, a regulatory attorney who spent 11 years observing and writing about utility commissions, including Louisiana’s, giving companies such unfettered access is “basically as if a criminal defendant can talk with a jury and judge behind the scenes without anyone knowing about it.”

“I don’t know of another public service commission that has the level of authority and the breadth and depth of jurisdiction without any—I don’t want to use the word ‘oversight’—but any other controls,” Burke said.

Louisiana is one of only 10 states with elected utility commissioners. According to data Floodlight analyzed in its months-long investigation, its commissioners receive more campaign cash from utility and oil and gas interests than their counterparts in any other of those states except Alabama.

Since 2014, the investigation found, power companies and fossil fuel interests have given a total of $13.5 million to elected utility regulators in nine of those 10 states—about 35 percent of all direct campaign contributions of $250 or more. (The remaining state, Nebraska, was excluded from the analysis because it has no private electric utilities.) That total does not count the millions of dollars funneled through political nonprofits that are not required to report their donors—hence the expression “dark money.”

Over the past decade, Floodlight found, Entergy Louisiana, its executives, and their family members, gave about $350,000 to PSC commissioners. For Cleco, the state’s second largest electric utility, the total was $206,000. (Neither company responded to requests for comment.)

Commissioners who responded to Floodlight’s inquiries insisted that such contributions don’t influence their decisions. “Hell no, I do what I want,” said Campbell, who has been on Louisiana’s PSC for 21 years. Over the last decade, he’s received more than one-third of his financial support from utilities and fossil fuel sources.

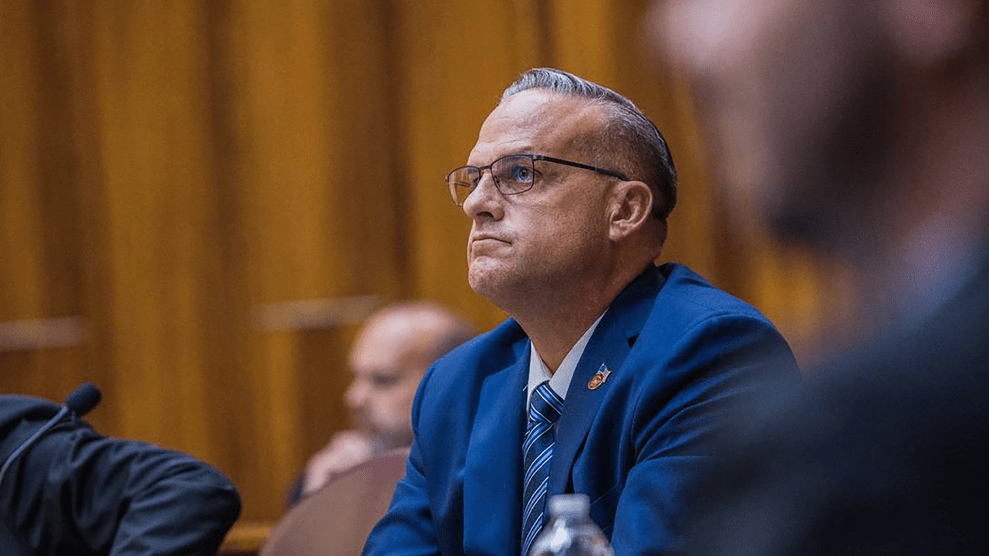

Commissioner Mike Francis, who has received half of his contributions from the same sources, says utilities support him because he’s making sound, business-centered decisions.

Louisiana’s utility commission is not overseen or directed by the legislature or the governor and is therefore uniquely situated to cut greenhouse gas emissions in the oil-friendly state by reducing its reliance on fossil fuels to produce electricity. But it rarely does.

In fact, based on figures from the US Energy Information Administration, Louisiana is tied for last among the 50 states for renewable energy use, with just 3 percent of its electricity coming from renewable resources.

In recent years, however, some commissioners have begun advocating for renewables and greater sustainability—namely Lewis, fellow Democrat Campbell, and swing Republican member Greene, whose seat is up for grabs.

In January, these three commissioners outvoted their colleagues to pass an energy efficiency program operated by an independent third party. Of the five commissioners, they are the ones who got the smallest share of their financial support from fossil fuel companies and utilities—Lewis has received just 11 percent, while Campbell and Greene each received 34 percent.

Opposing them on the energy efficiency issue were Mike Francis and Eric Skrmetta, who each got at least half of their support from those vested interests. Skrmetta even filibustered for nearly two hours while members of the audience at the meeting where the issue was decided chanted, “Vote! Vote! Vote!”

The candidates running to replace Greene include Jean-Paul Coussan, who has received 27 percent of his funding from utility and fossil fuel interests as of October 31, and Julie Quinn, with 26 percent. A third candidate, Nick Laborde, says he’s refusing all such donations and has received none to date.