Agustina Gastaldi Ferrario

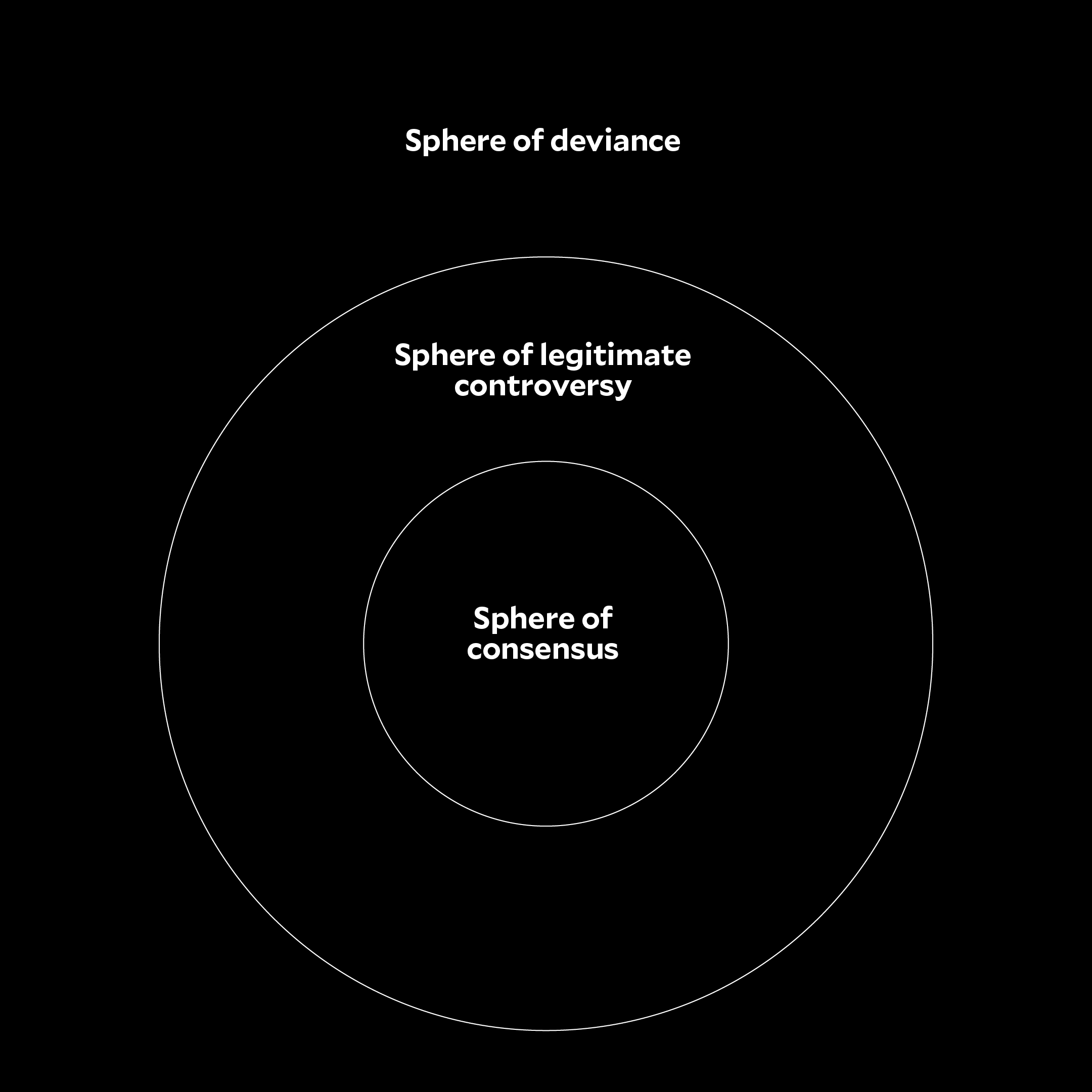

In 1986, Oxford University Press published The Uncensored War. An analysis by Daniel C. Hallin of media consumed in the United States during fighting in Vietnam, the monograph remains an important account of America’s first televised war. But a small diagram on page 117 would become the work’s greatest legacy: an illustration now referred to as “Hallin’s spheres.”

To visualize the model, imagine a target made of two concentric circles, surrounded by a vast hinterland of empty space. The smaller circle at the center represents the sphere of consensus, the region of “motherhood and apple pie,” Hallin writes. There, you can find all that is beyond question in US thought: democracy, American exceptionalism, American honor. The larger circle, the sphere of legitimate controversy, is where debates tend to take place: immigration, the economy, taxes. In the outermost region, the sphere of deviance, you find “actors and views which journalists and the political mainstream of the society reject as unworthy of being heard.”

The spheres helped Hallin explain why some ideas about Vietnam were naturalized, others were vigorously discussed, and many were dismissed as fringe. During the entire coverage of the war—thousands of TV hours—Hallin never found a single talking head utter the word “imperialism.” The idea lived only in the diagram’s outer layer, unallowable in discussions.

Today, most people know Hallin’s work through an heir: the Overton Window.

In recent years, the Window has become, as Politico argued, a “shorthand for the state of American politics”—a way to address the loss of a common middle ground during the Trump era. But its roots in conservative thought cannot help poking through.

In the 1990s, Joseph Overton, an executive at the free market think tank the Mackinac Center for Public Policy, built a cardboard-cutout window. In a popular version of the model, ideas were placed on a linear axis that ranged from the “unthinkable” on the far left, to the “popular” (and “actual policy”) on the right. Overton’s cutout could slide between these. This visualized how ideas had to move through several steps (“radical,” “acceptable,” “sensible”) before they reached their embodiment as laws. Ideas achieved political viability only when they fit inside the window frame.

Hallin’s spheres

In this way, the Window assumes a sequential public discourse, where the status quo is always at risk from the radical. Hallin’s spheres, by contrast, offer an X-ray of how discourse takes place. Hallin’s model does not ask how a new idea becomes normalized. Instead, it ponders why so many topics are considered outside allowable discussion.

The two frameworks have distinct visions. Hallin’s is descriptive. It reveals how radical ideas are pushed outside of public discourse. Overton’s is prescriptive. It serves as a model for changing the country’s laws.

As the more prominent, Overton’s model has saddled our views of what’s desirable with the weight of what’s politically viable. Using it, we begin to all think a bit like politicians. This limits our imaginations and directs our political creativity toward “sensible” objectives.

Within Hallin’s model, discussions do not become blandly about whether or not a once-radical notion was normalized, as they do within Overton’s.

“With Black Lives Matter we were moving toward a consensus on anti-racism” in certain parts of the country, especially following George Floyd’s murder, Hallin, now a professor emeritus at the University of California, San Diego, explained to me. “Then, the right started a big campaign to re-politicize race and focus on critical race theory.” Suddenly, calls for racial equality—a radical discussion worth having—drifted back out toward the realm of unacceptable in common discourse.

Hallin cites the January 6 attack on Congress as an example of the opposite. At first, the insurrection was considered deviant. “Then,” he said, “the Republicans made a big effort to push it back into the sphere of legitimate controversy.”

Fitting public discourse along a line that stretches between the unthinkable and the reasonable affects our perception differently than imagining public conversations as shifting across zones of consensus, controversy, and deviance, and wondering why that is. After 30 years of use and abuse, it may be time to set the Overton frame aside and give the spheres another spin.