40 Acres and a Lie tells the history of an often-misunderstood government program that gave formerly enslaved people land titles, only to take the land back. Read more revelatory stories here and listen to Reveal’s groundbreaking audio investigation here. This project is a collaboration between the Center for Public Integrity and the Center for Investigative Reporting.

Four days after Easter Sunday, a group of about 10 Confederate spies bedded down for the night at a South Carolina cotton plantation. For days the spies, who had grown up along these waterfronts, had tracked the Union’s naval movements along the rivers and beaches of the South Carolina Sea Islands.

But now, as they slept on the night of April 9, 1863, an enslaved man tipped off the enemy. The spies were captured by Union forces by the following morning.

“A Negro, James Hutchinson, betrayed us,” Townsend Mikell, one of the spies, recalled in his memoir. “Jim Hutchinson must have felt he had struck a mighty blow against the slaveholding plantation aristocracy, and procured his own freedom at the same time,” Edisto Island historian Charles Spencer would later write.

Hutchinson, the runaway slave, was Mikell’s half-brother. Their father, Isaac Jenkins Mikell, was among the most prominent plantation owners in the area. He lost hundreds of acres of land as the Confederacy fell and Union General William T. Sherman issued the battlefield directive known as Special Field Orders, No. 15, which granted plots of the seized plantation land in South Carolina, Georgia, and Florida to emancipated Black men and women.

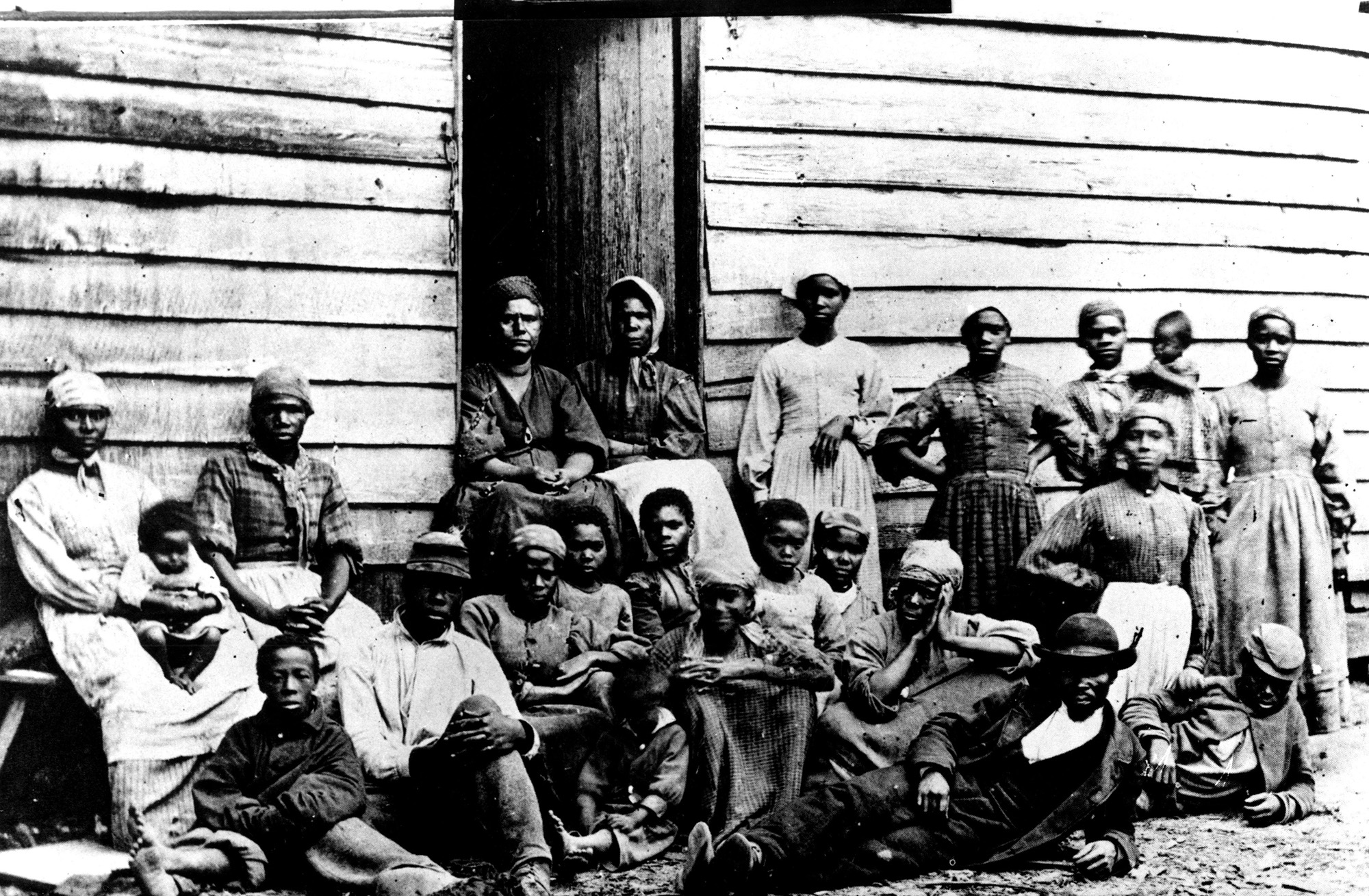

Runaway slaves who crossed into Union territory and military service members were given priority in the program. We found James Hutchinson’s name at the top of a list of Edisto-area freedmen who received 40-acre plots, one of more than 1,200 formerly enslaved people who received such land grants, identified by the Center for Public Integrity using recently digitized Freedmen’s Bureau documents.

However, in coastal South Carolina, the northernmost part of the country covered by the 40-acre orders, retaining that land came down to a legal fight over two words: “abandoned” and “evacuated.”

Federal law allowed the Union government to redistribute any land designated “captured and abandoned” during the war. But Isaac Jenkins Mikell and other Confederate land owners argued that they had merely “evacuated” the land, and thus were entitled to return to it. Ultimately, President Andrew Johnson sided with former plantation owners, stripping the land from the formerly enslaved.

Generations later, the Mikells and the Hutchinsons are two legendary families tied together by blood. They have been separated in life and law by the color line, once more by the Civil War and then again by the promise of a better life implied in the waning days of war, but abandoned in peace.

Today, their perspectives on the government’s decision that the plantation land belonged to the slaveholders and not the enslaved are still at odds.

“It was evacuated. We didn’t abandon it. We never intended to abandon it,” insists Pinkney Mikell—one of Isaac Jenkins Mikell’s great-great-grandsons—as he sits at the kitchen table of his home at Peter’s Point Plantation, a 180-acre waterfront plot on Edisto Island. Once planted in rows and rows of fine Sea Island cotton, this land was worked by hundreds of enslaved people. Like much of the island, it’s peppered with enormous live oaks bedecked in Spanish moss, and sustained by waterways, speckled with salt marshes.

“Thousands of enslaved people worked that land free of charge. Never got a dime for it. Barely got food to eat, got clothing once a year,” counters Theresa Jenkins Hilliard, Jim Hutchinson’s great-great-granddaughter, as if she’s sitting across the table from Pinkney.

“For someone to say that ‘I didn’t abandon my land, so I shouldn’t give it up,’ well, you were given the land,” she continued. Hilliard sits under a giant oak tree in a public park, 40 miles up the coast in Charleston. Her soft voice rises over the buzz of cicadas. “So you couldn’t give the people that worked that land for you for nothing, they don’t deserve any of it?”

We spoke with 10 descendants from each family about the modern-day relevance of Special Field Orders, No. 15, a battlefield directive that’s fundamental to the contemporary debate over slavery, reparations, and racial disparities in generational wealth.

Together, they personify the racial dimensions of the field orders and the national debate around the wealth gap and reparations.

According to a written family history, the Mikells first arrived in South Carolina from Scotland in the late 17th century. Five generations later, in 1838, a descendant named Ephraim Mikell bequeathed a “plantation called Peter’s Point” to his “son Isaac Jenkins and his heirs.”

Isaac Jenkins Mikell fathered more than a dozen children. Hutchinson family lore suggests that in addition to Jim Hutchinson he fathered at least two others with an enslaved Black woman named Maria, the Mikell family’s house servant. Mikell was so wealthy that, when he died, he left behind separate plantations to several of his white sons. Meanwhile, his Black sons, including Jim Hutchinson, were left nothing.

According to family oral history, Jim Hutchinson was a light-skinned Black man who never worked in the fields. He was fascinated by boats, navigating the local waterways, and assumed tasks like ferrying the Mikell family to church on Sundays.

When Special Field Orders, No. 15, came down, Hutchinson chose his 40 acres on Bayview, a waterfront plantation on Edisto Island, just across from the beach where the wealthy planter families summered. At least seven other freedmen also received possessory titles to land on Bayview.

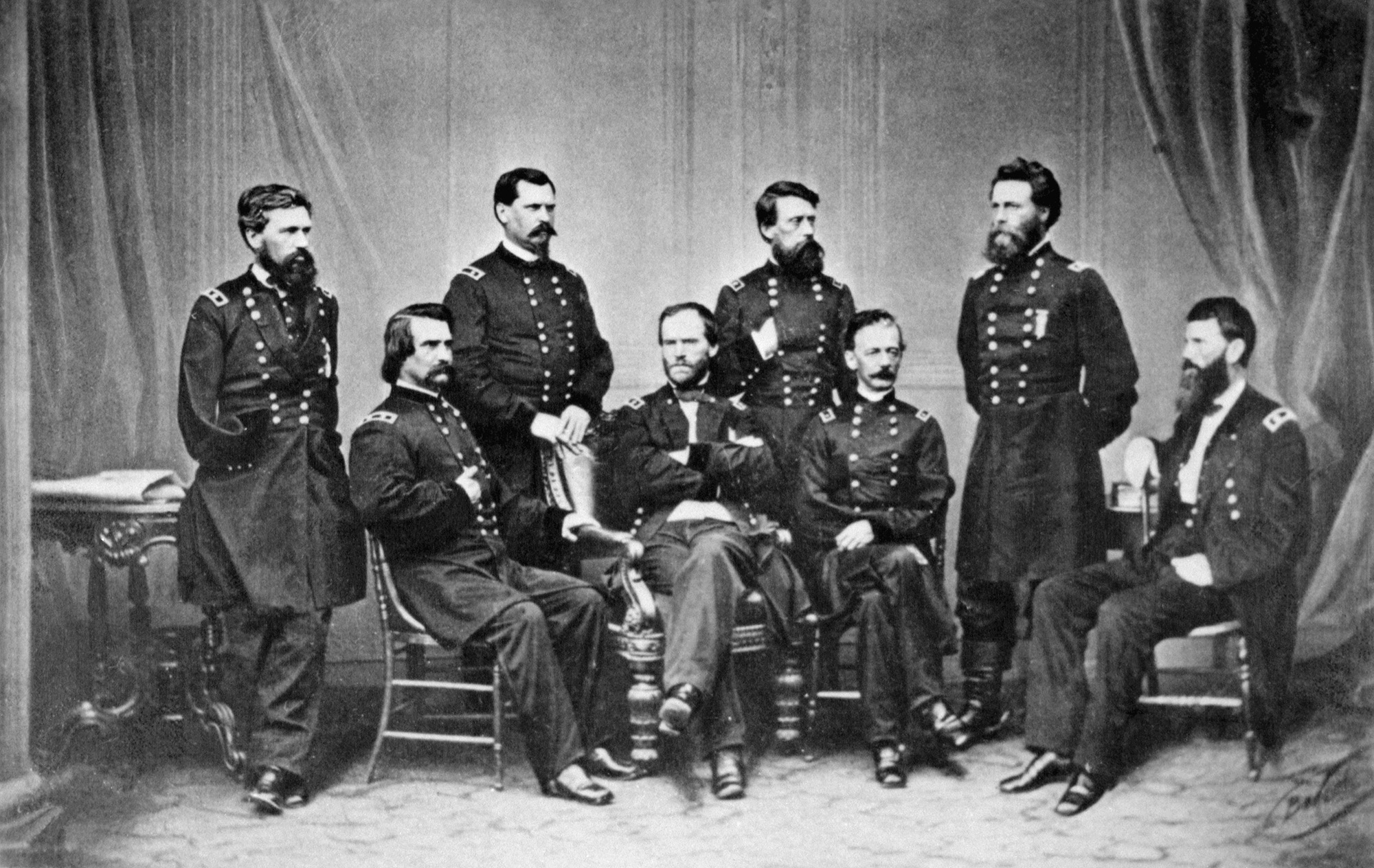

But just seven months later, Major Gen. Otis Howard, who ran the Freedmen’s Bureau, traveled to Edisto to deliver bad news. “A cavalcade of twenty negroes, mounted on horses and mules of all kinds and sizes, rushed down to the landing” to greet him, Mary Ames, a local teacher, would write in her diary.

Freedmen crowded into Trinity Episcopal Church, where Howard told them that President Johnson had pardoned former Confederate slave owners and returned land ownership to them. If the freedmen and women wanted to continue working the land they’d been given, they’d have to be hired back by their former slaveholders. “At first the people could not understand, but as the meaning struck them, that they must give up their little homes and gardens, and work again for others, there was a general murmur of dissatisfaction,” Ames wrote. “General Howard’s task grew more painful. He begged them to lay aside their bitter feelings, and to become reconciled to their old masters. We heard murmurs of ‘No, never.’ ‘Can’t do it.’”

The Mikell family had fled to the mainland during the Civil War, according to Rumbling of the Chariot Wheels, a 1923 book written by I. Jenkins Mikell, a son of the aforementioned Isaac Jenkins Mikell, who was a boy during the war. “We found that our houses, family dwelling house, and negro cottages had all escaped the ravages of war. But they were all in the possession of former slaves,” he wrote. “Our venerable church, whose charter of corporation was near two hundred years old, was firmly held by colored members of the ante-bellum congregation, who refused to vacate.”

It was only after official documents came from Washington, proclaiming the Mikells as the rightful owners of the land, that they were able to reoccupy Peter’s Point Plantation. Ultimately, the Mikells signed labor contracts with dozens of freedmen and women who had been formerly enslaved in Edisto and who agreed to work the plantation.

Hutchinson was not among them. He and several other freedmen pooled funds, purchased acreage on other former plantations, and divided the parcels among themselves. Hutchinson’s share was 230 acres, nearly six times the 40-acre allotment.

“After the war, Jim was known as one of the ‘Black Kings of Edisto,’ a group of men who had risen out of slavery and become successful farmers, businessmen, and leaders of the community,” according to “The House That Hutchinson Built: Preserving a Touchstone to Edisto Island’s Black History.” The article, published by the National Trust for Historic Preservation, details how he went on to partner in a successful Black-owned ferry company and serve as a local Republican precinct chairman. “He was an outspoken advocate for African American voting rights and property ownership.”

But on July 4, 1885, during an Independence Day party at the home of Lewis Hutchinson, one of Jim’s sons, a brawl broke out between the Hutchinsons and a white store owner named Frederick J. Barth. During the melee, Jim Hutchinson was shot in the groin and killed. Barth would later claim he’d fired accidentally, but both he and a companion named E. Julian Bailey were charged with murder.

“The death of Hutchinson, whose courtesy, industry and general good behavior had gained for him the respect and confidence not only of his own race but of the entire community, is sincerely regretted,” the Charleston News and Courier reported at the time. “It is the earnest desire of all that the perpetrators of this crime shall suffer for it, be whom they may.”

According to the newspaper’s coverage of the trial, the courtroom was packed given “the fact that the accused are white men and that the deceased was a prominent Edisto Island negro owning considerable property and occupying a conspicuous position in politics.” It added that Major John Jenkins and Mr. John F. Townsend, two prominent residents of Edisto Island,” showed up to testify that Jim Hutchinson was a “physically powerful man…known to be inimical to the white race.”

Ultimately, Bailey was cleared of the charges. Barth was initially convicted of manslaughter, but later appealed and was acquitted.

HR 40 is a US House bill, named for 40 Acres and a Mule, to study reparations. It’s been introduced in every Congress since 1989, but it only passed out of the judiciary committee once, in 2021, and wasn’t brought up for a floor vote.

Among the issues of national reparations linked to slavery is the difficulty of determining which individuals today should receive redress for injustices that took place a century and a half ago, and who should pay for them.

Many family lines are not as clear as that of the Mikells and Hutchinsons, and multigenerational family trees often are entangled in discrepancies in legally acceptable documents like wills and land ownership records necessary to resolve disputes over inheritance.

In addition, many Black Americans whose financial fortunes have been hampered by racism are not descendants of formerly enslaved people in the United States.

Today, many of Isaac Jenkins Mikell’s descendents—both Black and white—still live on Edisto Island, where some chitchat at the grocery store or open their homes to each other to socialize, even as they remain at odds over what should have become of the land he and other wealthy planters left behind.

“Jenks” Mikell, 82, lives in the same home on Peter’s Point Plantation as did his forefathers. He feels protective of the family legacy and bristles at the suggestion that the descendants of the formerly enslaved are entitled to any form of redress.

“If we keep giving away stuff, that’s all we’re gonna be able to do is give away,” said Jenks, a former life insurance salesman. “Nobody ever gave me anything other than this,” he said in reference to the plantation land. “But I now had to sweat bullets to keep it.”

His younger brother, Pinkney Mikell, 73, is less definitive. He’s okay with reparations for more recent forms of racial discrimination. “I’m clearly a white guy who’s benefited tremendously by privilege and the Civil War and everything else,” he notes.

Pinkney believes those reparations ought to be societal; otherwise, the wealth gap will never narrow. But he isn’t willing to give up his own land as a form of reparations. “I’ve been looking at reparations ideas since I was 20 years old and I always come back to, how do you fix this?…I’m not St. Francis. I mean, I’m not gonna give it away or sell it,” Pinkney said. “But I don’t know how you manage that. It’s a conundrum. It just leaves me baffled.”

Hutchinson’s descendants see things differently. While many of them have found success—one of them, Emily Meggett, was a well-known Gullah Geechee cook who died last year at age 90—they say their trajectories could have been different had their family not had Edisto Island land taken back from them. (Gullah Geechee are descendants of enslaved people brought to the Sea Islands, known for their distinct dialect and traditions that retain elements of West and Central African culture.)

Greg Estevez, another descendant of Jim Hutchinson, mostly grew up on Edisto Island, before leaving for two decades of Naval service and eventually settling in Jacksonville, Florida. He regularly drives up to Edisto, and has written books about Black life there. On a sticky Saturday in July, he gives me and a Reveal producer a tour of the island. “These houses, you can tell that people are not as wealthy,” Estevez says, “but these people have been here for years.”

Estevez parks his car outside Hutchinson House, a small two-story, forest-green house with a red tin roof that dates to about 1885. The house is named for Jim Hutchinson’s son, Henry, who built the home on land that his father had purchased 10 years out of slavery.

“You know, when people say wealthy, what really does that mean?” Estevez, 59, asks. “Does that equate to money? No, it doesn’t. Wealthy means the accumulation of knowledge, the accumulation of [tangible] things that could be passed down from generation to generation…And that’s the missing link to a lot of African American families even today.”

There are many more families just like the Mikells and the Hutchinsons. Families that mix but hardly blend. One side Black, the other white, both still reckoning with Special Field Orders, No. 15, and its aftermath.

The land that Jim Hutchinson got as part of his 40 acres is beautiful, and valuable, real estate today, but his family missed out on that part of their inheritance.

“To me, it just goes without saying,” says Hilliard, a retired government worker. “We worked for 400 years for absolutely nothing. And then you have the others who are still enjoying the benefits of that wealth that their forefathers earned on the back of the enslaved people for the past 400 years.”

This project is a collaboration between the Center for Public Integrity, the Center for Investigative Reporting, and the Investigative Reporting Workshop. Read more here.

Top illustration: Michael Johnson: Source images: Photo12/Universal Images Group/Getty; Rosana Lucia; Nadia Hamdan; National Archives (2)