Mother Jones; Marc Studer

More than 100 million Americans have medical debt, with half owing more than $2,000; disabled people are twice as likely to have it than those without disabilities. Annually, around half a million Americans are pushed into bankruptcy by health care costs. That’s understandably made medical fundraising through websites like GoFundMe appealing, with Americans seeking a combined $10 billion from 2010 to 2018 for health expenses. But publicly asking for financial support can also be a hindrance, affecting how crowdfunders are seen and treated by the wider public—even in a country where most are acutely aware of how health insurance is tied to jobs, and how insurers can fight not to cover many procedures and medications.

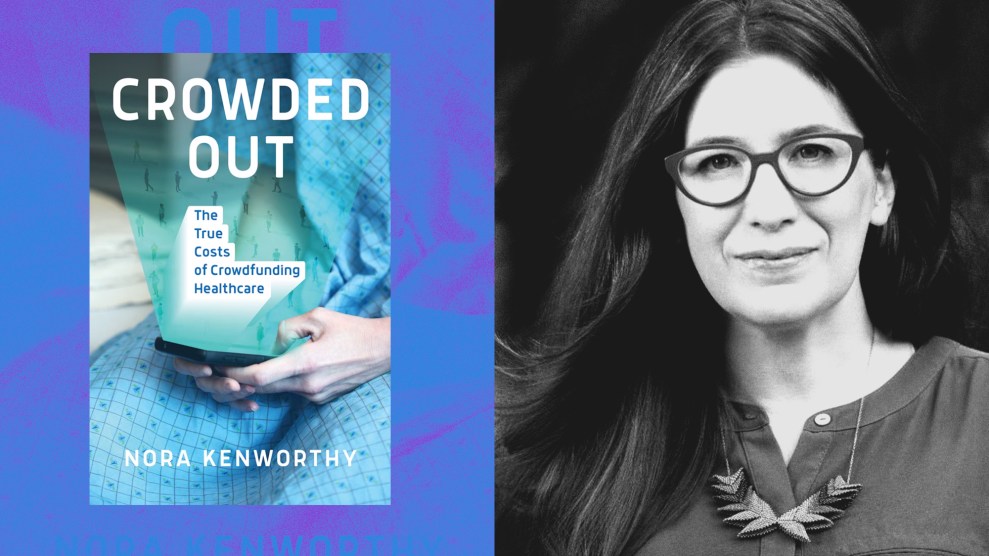

Between 2016 and 2020, only 12 percent of United States–based GoFundMe medical fundraising campaigns met their goals, according to a 2022 study. More than that, 16 percent of campaigns received no donations at all. One of the study’s authors, University of Washington professor Nora Kenworthy, has taken a dive into the landscape of US medical fundraising in a new book, Crowded Out: The True Costs of Crowdfunding Healthcare.

Kenworthy talked to Mother Jones about how the US private health insurance model fuels medical debt, biases that shape who people consider worthy of donations, and what medical fundraising could look like in the future—even if Congress did listen to its constituents and pass legislation enacting a more socialized healthcare system.

How has the American private insurance model contributed to the rise of medical fundraising sites like GoFundMe?

Crowdfunding for healthcare expenses exists in lots of parts of the world—there are places like the UK and Canada, that have better health systems than we do, where people still rely on crowdfunding for a lot of uncovered healthcare and expenses associated with [it], like child care, that are still hard to pay for. But in the United States, we have a tremendous amount of crowdfunding. That seems to really arise from either things that are not covered by insurance, are covered inadequately, out-of-pocket costs that are incredibly high, or from people who are not insured, or underinsured, when they experience illness or accidents.

We live in a very capitalistic country. How does that shape people’s feelings about their own medical debt, asking for help with it, and contributing to other people’s medical expenses? Is it a source of shame, or has it been normalized?

Some of the kinds of social norms that really are deeply rooted in the United States both push people towards crowdfunding and also make it a really difficult thing for people who most need it to use successfully. We have a very extreme idea of individualism, like, “If you can’t fix it, you’re kind of on your own.” Or that the person with the most merit should win out, even when a lot of the ways that we measure merit are very much linked to privilege and racial identity and class identity and things like that. I write about the way that all these play out in the marketplace of crowdfunding, and get projected onto people’s crowdfunding campaigns.

Feelings of shame, particularly about having to start a campaign for yourself, are exceedingly common. In interviews, I’ve also talked with people about the very acute shame that they felt in terms of having to ask for help. On the other hand, starting campaigns for other people is seen as less shameful. If someone starts a campaign for you, then that taps more into this idea of wanting to help each other, and we are also a very charitable society. That is also a result of our very capitalist and neoliberal systems: we rely a lot on each other in order to meet basic needs because so many of us are made vulnerable by these economic systems.

As you note in your book, white people’s medical campaigns tend to go viral more often than people of color’s. Can you speak to that?

It’s important to say that the top level of racism that’s operating here is really structural racism, and the racial wealth gap, which is enormous in the United States. The way that that comes into play is that campaigns started by or on behalf of people of color, but particularly Black people, tend to do less well than campaigns for other people. There’s also an interpersonal racism and racial bias element that is playing out here, particularly with campaigns that go viral or get lots of exposure. That’s the kind of internalized biases and overt racism that we might bring to the way that we regard and read and look at campaigns that can translate as people viewing campaigns with more suspicion, more tendency to think about them as fraudulent, or more likely to blame the person who’s in need.

We see that especially with viral campaigns. I did a research project with some amazing researchers, Aaron Davis and Shauna Elbers Carlisle. What we looked at the top most viral medical campaigns in GoFundMe’s history, and so that was about 900 campaigns that had raised over $100,000. In that group of 900, we found only five were on behalf of Black women, and of those five, two had been started by white people. That, to us, speaks to these incredibly huge disparities that are happening at that more viral level of campaigns, and how people’s campaigns are being treated very differently by the crowd.

Genetics, environmental exposure, and poverty can all contribute to the development of chronic health conditions. Yet, it can be harder to fundraise for conditions where some people blame the patient, like those who have Type II Diabetes. How does that shape crowdfunding efforts?

The really large structural factors—the neighborhood you live in, or how much money you have, or the air around you—shape the the likelihood of your becoming ill over your lifetime. Particularly when it comes to chronic health conditions, whether that’s diabetes, or congestive heart disease, or cancer; these chronic conditions are very much shaped by big factors that are out of our control. When we’re crowdfunding, we’re often looking for the solvable problem, right? For an individual, [that means] “If I can just give you this one thing, then you’ll be okay.” That’s really hard to deal with in chronic conditions.

I talked to a lot of people with diabetes, both Type I and Type II, who are reliant on insulin to survive. It’s really hard to crowdfund for insulin every month. Even when we know that the cost of insulin is absurdly high, and we understand that people need it, and if they don’t get it, they’re truly not going to survive. It’s really hard for people to find ways to use crowdfunding to solve those kinds of ongoing chronic issues. People talk to me about exactly what you’re describing: feeling blamed for their conditions, and feeling like they’re being judged by the crowd for what has happened to them. We see crowdfunding reinforcing and amplifying, and almost kind of fueling, these individual-level judgments of who’s deserving and who’s not.

Legislation like Medicare for All could reduce further medical debt—but would it get rid of the need for medical fundraising? Where could we still see it?

What we think of as a universal health coverage system not only reduces future medical debt, but could also reduce the amount that people have to pay for certain things like insulin. A more universal system can protect people better in those periods of vulnerability. But we know that illness, particularly acute or severe illness episodes, requires lots of different kinds of social support. There are things that even very well-funded universal health systems do not cover, whether that’s experimental treatments, childcare, or perhaps specialized foods that you might be forced to take. I don’t think we should think of all crowdfunding as bad. It has the potential to meet some important needs that fall outside of formal systems.

At the same time, I think we need to remain aware of the ways that crowdfunding in its current form in the US is actually undermining the efforts that are being made to move towards more universal healthcare systems, because it’s reinforcing these ideas that not everyone deserves the same thing. That we’re all individuals, and we’re on our own when we get sick, or the idea that a marketplace mentality can be the best option for fixing these kinds of societal challenges.

All of those ideas really run completely counter to the moral ideas that undergird a more universal medical coverage system. Medicare for All is based on the idea that when people are sick, they deserve help, regardless of how good a person they are, what the color of their skin is, or how much they make. It’s the idea that we have a safety net that actually catches everyone. And that idea is just not there in crowdfunding. Crowdfunding is really kind of undermining our commitment to some of these more universal ways of supporting each other.

This interview has been lightly edited for length and clarity.