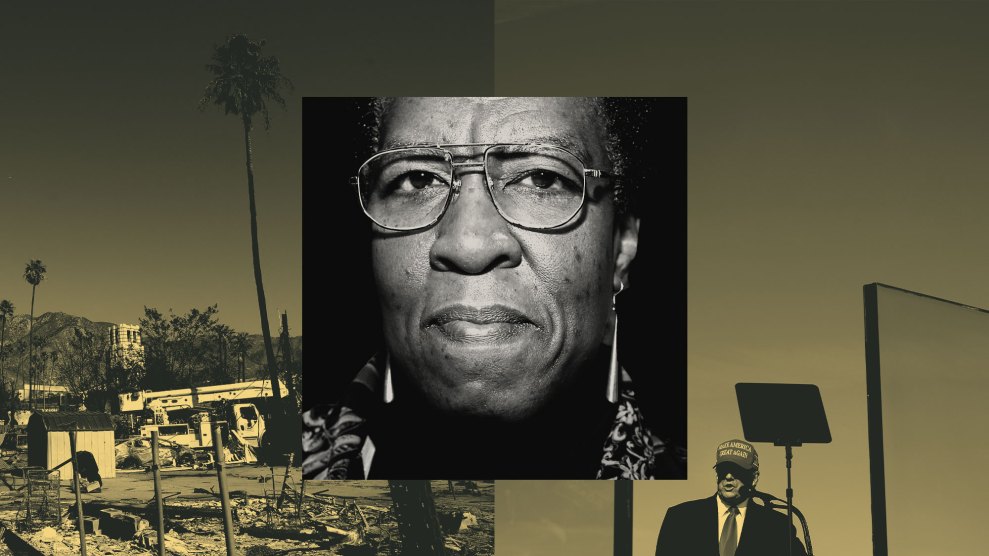

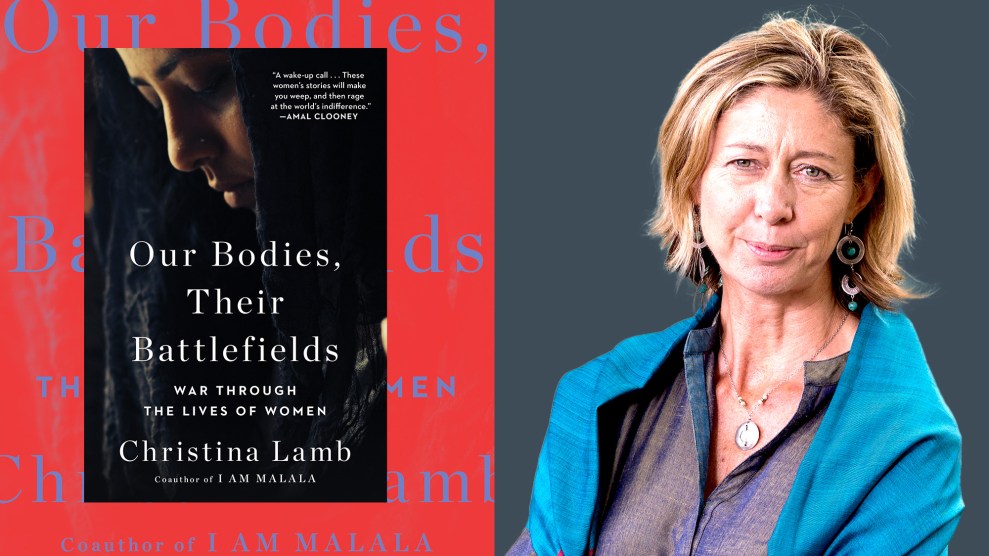

Mother Jones; Roberto Ricciuti/Getty

Despite being “the cheapest weapon known to man,” sexual violence in war is “almost always ignored in the history books,” writes journalist Christina Lamb in her 2020 book, Our Bodies, Their Battlefields: War Through the Lives of Women.

In the book, Lamb, the chief foreign correspondent for the Sunday Times in Britian, tried to change that. She investigated the history, and human impact, of rape as a weapon of war—documenting its use by Pakistani soldiers against Bangladeshis in the 1971 war for independence; by Serbian paramilitary soldiers against Bosnian Muslims in 1992; and by ISIS against the Yazidis during and after the 2014 genocide, among many other conflicts throughout history.

After the October 7 attack on Israel by Hamas, Lamb went to Israel to investigate allegations of sexual violence. She published a report in early December, highlighting Israeli activists’ frustrations with the initial silence on the allegations of widespread rape from the United Nations and other international bodies.

Earlier this month, the office of UN Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict, led by Pramila Patten, released a report that found “reasonable grounds” to believe sexual violence—including rape and gang rape—occurred during the Oct. 7 attack. It did not establish the prevalence of sexual assault or attribute it to Hamas or other specific individual actors. The report also said there is “clear and convincing information” that sexual violence occurred against Israeli hostages—and likely remains ongoing for those still held in captivity; last week, the New York Times published the account of the first former Israeli hostage to say she was sexually abused while held by Hamas.

But the release of the report hasn’t quelled critiques—including from Lamb, who told me she thought it was “inexcusable” that the UN didn’t respond sooner to Israeli women’s groups who allegedly requested months ago for the body to look into the allegations of sexual violence on and after Oct. 7. American officials also said the UN erred, alleging in December that they were ignoring reports of sexual violence against Israelis in the conflict, the New York Times reported. (Patten’s report recommends a full investigation.)

Still, the investigation and discussions of rape during the war have been fraught. Historically, the abuse of women has been used to justify conflict—including the US’s role in Afghanistan, as my colleague Madison Pauly reported back in 2021. Since the beginning of the war, critics have questioned how reports of sexual violence on Oct. 7 are being used by Israel and its allies to legitimize its campaign in Gaza.

On International Women’s Day earlier this month, Israel released an ad showing women around the world saying that they are “unite[d] in soldiarity with their Israeli sisters, who were kidnapped, raped, and brutally murdered on Oct. 7th. No woman should endure such horrors at the hands of terrorists.”

Last month, protesters confronted former Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and US Ambassador to the UN Linda Thomas-Greenfield at an event on sexual violence in conflict at Columbia University, alleging the panelists were “exploiting” the allegations to justify Israel’s actions, which have killed more than 32,000 people.

There has also been heavy criticism of a December investigation in the New York Times, based on more than 150 interviews, which alleged “Hamas weaponized sexual violence on Oct. 7.” The story drew criticism from within the Times, according to The Intercept, and from readers who pointed to discrepancies in some of the accounts. The reporters subsequently addressed some of the critiques. But last week, separate journalists from the Times uncovered video evidence that undercuts an allegation from an Israeli source featured in the December investigation, who alleged two teenagers killed on Oct. 7 were subjected to sexual violence.

Critics have also alleged the focus on sexual violence in the war has ignored how abuse and harassment also affects Palestinian women. The UN report included claims that in the occupied West Bank sexual violence has been perpetrated by Israeli officials and settlers against Palestinians in detention, in their homes, and at checkpoints. And on Thursday, Reuters published a story alleging that dozens of social media posts show Israeli troops in Gaza playing with women’s underwear. (The IDF said in a statement to Reuters it investigates incidents of inappropriate behavior but did not clarify whether it was referring to any of the incidents reported by the news agency or whether it had taken action against any of the soldiers featured in the posts.)

Lamb, for her part, resents how allegations of sexual violence have become political pawns in discussions of the war. On a Zoom call and over email this past month, I spoke with Lamb about the difficulties of reporting on sexual violence in conflict, why it’s so seldom prosecuted as a war crime, and what she makes of the recent discourse around sexual violence in the conflict between Israel and Hamas.

This interview has been lightly condensed and edited.

What have you made of the discussions of sexual violence in the context of Israel’s war on Gaza since Oct. 7?

This is a very particular situation, I would say, because it’s a very polarizing conflict. Not that that isn’t the case, I suppose, with Russia and Ukraine, but people outside of the main countries involved seem to have taken positions in a way that isn’t always the case [with other wars]. A lot of people seem to think it’s not possible to think—as I do—that what happened on October 7 is absolutely horrific, but also what Israel is doing in Gaza is horrific.

After I covered the UN report earlier this month, the main critiques I heard from people critical of Israel were that the UN team didn’t speak to the survivors of sexual violence [the report says the ones who are still alive are “undergoing specialized treatment” for severe trauma]; that the UN team had the full cooperation of the Israeli government in producing this report, and could therefore have been presented with pro-Israeli propaganda; and that the UN team couldn’t establish the prevalence of sexual violence on or after Oct. 7, which would require further investigation. How should critics balance their skepticism of the UN’s findings, given Israel’s history of propaganda, with an understanding of some of the difficulties of actually gathering evidence of this kind of crime?

I’m the last person to be an apologist for the Israeli government and what they’re doing. I was also a bit concerned when I wrote my piece, you know, the last thing you want is for it to be used in any way as a sort of justification for what they are doing and terrible things that they’re doing in Gaza.

But I don’t think we should say, “Well, we’re not going to report this because we’re worried that it could be used as justification.” That would be wrong—people have said, “Why are we not reporting what Israel is doing to the Palestinian women?” I think we should report that too.

But in terms of the critiques of the [UN] evidence—often, women don’t come forward for years. I mean, I’ve written about women who’ve taken 60 years to come forward and talk about this. This is a really difficult thing to talk about. It’s very personal. We all know that rape is sadly the one crime where the victim is often made to feel that they’ve done something wrong, so they don’t want people to know. I think it’s possible that the majority of the victims in this case were killed or taken hostage. My understanding is that there are some survivors but they’re deeply traumatized and in psychiatric care. I’d also say that you don’t always have to have the body. You can write about and report on a murder without having the body.

I can see why the women in Israel were angry at the beginning because they wrote to all these bodies, like hers, which is supposed to look into these things. There was no response.

[Editor’s note: Lamb is referring to the office of Pramila Patten, the UN’s Special Representative of the Secretary-General on Sexual Violence in Conflict. Reporting from the New York Times said that Israeli women reached out to the office of UN Women—which is technically separate from Patten’s office—and got no response. UN Women directed our questions to Patten’s office, which did not respond to a request for comment to verify if Israeli women had contacted the UN about investigating sexual assault and if there had been a response.]

I think that that is actually inexcusable. I think, when these different women’s organizations contacted [the UN], they should’ve responded, they shouldn’t have just been completely silent. As these Israeli women’s groups said, [the UN] supported women in Iraq, Ukraine, Afghanistan, and all these other places.

Can you help parse the distinction between individual acts of sexual violence that the UN says it has “reasonable grounds” to believe occurred on October 7, versus the systemic use of it, which they’ve said they can’t yet establish because that would require further investigation?

Both cases are horrific. But there is a difference between rape happening because of the breakdown of society and people actually being ordered to go and rape. It seems to me, unfortunately, in recent years, we’re seeing this happening more and more, so [in my book] I specifically looked at cases where people had been ordered to rape.

The IDF claims that they’ve got intercepts and they’ve interrogated people who said that they were sent to do it. Now, some people have said to me, “Hamas says they respect women, they would never do this.” I’m sorry, but I have many cases in other countries where it’s been Islamic groups that carried out [rape]—for example, the Yazidis, that was [ISIS]. You can’t say, “This religion honors women and therefore wouldn’t do it,” which is an argument I’ve had a surprising number of people make. Unfortunately, every religion is doing it, every conflict, every kind of ethnicity, pretty much—it’s just a very effective and cheap weapon. The real problem, the real question we should be asking, is: Why isn’t anything being done, really, to bring perpetrators to justice so that this [rape] isn’t used?

You’ve written about how rape wasn’t prosecuted as a war crime until 1998, when the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda handed down the conviction for rapes during the Rwandan genocide. And there’s still been no prosecution of Boko Haram’s sexual violence against Nigerian girls and women, and only one prosecution of an ISIS fighter for sexual violence against Yazidis. Why is sexual violence in conflict so rarely prosecuted as a war crime?

I think that one of the main reasons is because it’s something that happens to women. Doctor [Denis] Mukwege, who is one of my heroes, who got the Nobel Peace Prize [in 2018] for his work in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, treating rape victims and raising this issue—and his hopsital has treated thousands of women and girls who’ve been raped—he says if this was happening to men on a wide scale and men were being, you know, sexually mutilated and traumatized by women, do we really think that the world would have stayed silent?

Also, people don’t see any upside, really, in reporting [their experience of sexual violence to authorities] because they fear that they will be castigated and seen in a bad light, but also they don’t believe that it will achieve anything, because they don’t think anyone will be brought to justice.

You wrote about how there has been barely any media coverage of sexual violence as part of the war in the Democratic Republic of Congo; the UN says there were more than 31,000 cases in the first three months of last year alone. Sexual violence perpetrated by Russians against Ukrainians, on the other hand, has been widely covered in the media, as you’ve said. Why are some instances of sexual violence in conflict more widely acknowledged than others?

To be fair, with the DRC, the whole kind of war there was very little covered anyway. Around five million people died, and there was very little coverage. [Editor’s note: The Times notes some estimates even put the death toll in the Congo at over six million.]

I think it’s complicated to cover, it’s difficult to get there—there was a lot of discussion of, why have we covered so much of what’s happening to Ukraine? Is it because they’re people that look like “us”?

But I feel very strongly that we should cover all of these things, and it worries me a lot that, because there’s so much focus on Ukraine and Israel, that we start neglecting [other places].

How do we know if sexual violence is not happening in certain conflicts, or if it’s just not being adequately covered or researched?

I’ve been a war correspondent for 36 years, yet until I started looking into this, I had no idea how widespread it was. And once I started looking into it, I realized there’s pretty much no conflict where it doesn’t happen, and that lots of wars widely reported in the past actually had a lot of rape happening, yet it wasn’t reported. Look at the Spanish Civil War, where a lot of female reporters went for the first time—such as Martha Gellhorn, Virginia Cowles, and Lee Miller (who I grew up idolizing) yet they didn’t report on this, and that intrigues me. Did they not see? Because, actually, many, many women were raped. Now I look at their reporting and I think, you must have seen that this was happening to women, because it was happening so much, and yet you never wrote about it—why?

Do you have a sense of how these questions apply to sexual violence experienced by Palestinians? The UN report seems to suggest there are structural barriers to Palestinian victims coming forward that lead to a perception of little sexual violence inflicted upon them by Israelis.

Well that’s true, in many societies and it’s always difficult for women to talk about these things—rape is the one crime where the victim is often made to feel they did something wrong. That’s why I feel so angry when they do come forward and we don’t do anything.

But also, I think we’re talking about two different things—sexual violence in conflict as a weapon of war and people being raped or sexually abused in detention, which we’ve seen happening to protesters in detention in Iran and Belarus. I think there has been coverage, though I must admit, when I reached out to Palestinian groups on this in December, they did not put me in touch with any women who would speak about it.

Ironically, in my book I wrote—quoting academic research—that the Israel-Palestinian conflict was one conflict where [sexual violence] seemed to happen less, and I speculated that this was because there were a lot more women involved on both sides. It’s clear to me, the more women you have in the military or as peacekeepers, then you have a less macho culture, and it seems to make a difference. But you know, unfortunately, everywhere that I looked, it seems to happen.

Update, April 1: This story has been updated with a response from UN Women.