This story is adapted from Ari Berman’s new book, Minority Rule: The Right-Wing Attack on the Will of the People—and the Fight to Resist It, which will be published April 23.

A day ahead of the third anniversary of January 6, President Joe Biden traveled to Valley Forge, Pennsylvania—where George Washington encamped during the Revolutionary War—before delivering what he described as a “deadly serious” speech framing the stakes of the 2024 election. Biden wanted to show how Donald Trump, by inciting the insurrection and trying to overturn the 2020 results, had violated the most basic principles in a democracy: free and fair elections and the peaceful transfer of power.

“Today, we’re here to answer the most important of questions,” Biden said. “Is democracy still America’s sacred cause? This is not rhetorical, academic, or hypothetical. Whether democracy is still America’s sacred cause is the most urgent question of our time, and it’s what the 2024 election is all about.” The alternative, Biden said, was “dictatorship—the rule of one, not the rule of ‘We the People.’” That fundamental tenet of American democracy was gravely imperiled, Biden warned: “We’re living in an era where a determined minority is doing everything in its power to try to destroy our democracy for their own agenda.”

That’s undoubtedly true. But the crisis Biden described—and the choice facing the nation this November—is much older and deeper than Trump. A determined minority has been trying to shape the foundations of American governance for their own benefit since the inception of the republic. For more than two centuries, a fierce struggle has played out between forces seeking to constrict democracy and those seeking to expand it. In 2024, the country is once again immersed in a pivotal battle over whom the political system should serve and represent.

From childhood, we are taught to venerate the Constitution as a civic religion, but the truth is that America’s democratic experiment has been defined since the nation’s founding by a central tension over whom the government should favor. The United States has historically been a laboratory for both oligarchy and genuine democracy. And to grasp the present-day fight, one must understand the long-standing clash between competing notions of majority rule and minority rights.

This story is adapted from Ari Berman’s new book, Minority Rule: The Right-Wing Attack on the Will of the People—and the Fight to Resist It, which will be published April 23.

The founders, despite the lofty ideals in the Declaration of Independence, designed the Constitution in part to check popular majorities and protect the interests of a propertied white upper class. The Senate was created to represent the country’s elite and boost small states while restraining the more democratic House of Representatives. The Electoral College prevented the direct election of the president and enhanced the power of small states and slave states. The makeup of the Supreme Court was a product of these two undemocratic institutions. But as the United States has democratized in the centuries since, extending the vote and many other rights to formerly disenfranchised communities, the antidemocratic features built into the Constitution have become even more pronounced, to the point that they are threatening the survival of representative government in America.

The timing of our modern retreat from democracy is no coincidence. The nation is now roughly 20 years away from a future in which white people will no longer be the majority. New multiracial coalitions are gaining ground in formerly white strongholds like Georgia. To entrench and hold on to power, a shrinking conservative white minority is relentlessly exploiting the undemocratic elements of America’s political institutions while doubling down on tactics such as voter suppression, election subversion, and the censoring of history. This reactionary movement—which is significantly overrepresented because of the structure of the Electoral College, Congress, and gerrymandered legislative districts—has retreated behind a fortress to stop what it views as the coming siege.

To justify a deep hostility to broad-based political participation, conservatives have long pointed to the notion that the United States was never intended to be a true democracy. But those cries have gotten more pointed. “We’re not a democracy,” Sen. Mike Lee (R-Utah) tweeted on October 7, 2020. It was not “the prerogative of government to reflexively carry out the will of the majority of its citizens,” he maintained. Three months later, a mob that explicitly presented themselves as heirs to the American Revolution stormed the US Capitol to overthrow the will of a majority of voters.

And now they want to finish the job. “Welcome to the end of democracy,” far-right activist Jack Posobiec snarked at the Conservative Political Action Conference in February. “We are here to overthrow it completely. We didn’t get all the way there on January 6, but we will endeavor to get rid of it.”

Our government was built upon a series of compromises that were meant to hold the new nation together. These decisions, however, ultimately laid the groundwork for the divisions that are ripping the country apart today, when extreme forces are openly talking about destroying democracy. The founders, in ways they could not have anticipated, placed a ticking time bomb at the heart of American politics. The structural inequalities built into the system have exploded before, most notably leading to the Civil War. But like a law of physics, these problems are accelerating, with one inequity exacerbating another. The country is again at a major inflection point concerning race, political power, and representation. If the framers once feared what James Madison called “the superior force of an interested and overbearing majority,” the central threat now facing American democracy is minority rule.

In the late spring of 1787, 55 of the most illustrious men in America gathered in Philadelphia to draft a new constitution for the United States and, in Madison’s words, “decide forever the fate of Republican Govt.”

Standing at the back of the Pennsylvania legislature’s assembly room, Edmund Randolph, the tall and handsome 34-year-old governor of Virginia, took aim at the governments of the 13 states, which in the minds of nearly all of the delegates had led the country to the brink of collapse by being too solicitous of the common man. “Our chief danger arises from the democratic parts of our constitutions,” Randolph said. “It is a maxim which I hold incontrovertible, that the powers of government exercised by the people swallows up the other branches. None of the constitutions have provided sufficient checks against the democracy.”

The purpose of the convention was for the Articles of Confederation—the country’s original constitution ratified in 1781—to be “corrected and enlarged.” But in order “to restrain, if possible, the fury of democracy,” Randolph laid out a blueprint, conceived by his fellow Virginia delegate Madison, for a new national government to replace the Continental Congress and counter the power of the states.

Under what was dubbed the Virginia Plan, the House of Representatives would be elected by the people, like the state legislatures, but would be accompanied by an upper chamber, the Senate, whose members would be nominated by the state legislatures and chosen by the House. (It wasn’t until 1913 that senators were elected by the voters.) The new national legislature would choose the country’s president and appoint its judiciary. That meant the public would directly elect only one house of one branch of the federal government.

This marked a radical turnaround from the Declaration of Independence that had been signed in that very room 11 years earlier. The declaration held that governments derived “their just powers from the consent of the governed.” It was “the mother principle” of the revolution, said Thomas Jefferson, that “governments are republican only in proportion as they embody the will of their people, and execute it.” The state constitutions subsequently drafted in 1776 placed the bulk of power in popularly elected legislatures that were expected to reflect and encourage democratic participation. Legislators were elected annually, with the slogan “where annual elections end, tyranny begins” so that they would be as accountable as possible to the public. Ordinary citizens clung fervently to the notion of “vox populi, vox dei”: “the voice of the people is the voice of God.”

Of course, many people were still excluded from the political process. Property requirements made more than a quarter of white men ineligible to vote, women could vote only briefly in New Jersey, and free Black men were allowed to cast ballots in just six states. The 700,000 enslaved people had no legal rights, and Native Americans were not even considered US citizens. Still, by the standards of the time, the postwar legislatures were far more reflective of everyday society than the colonial ones, which had been dominated by wealthy merchants and lawyers.

This new democratic egalitarianism might have defined America’s political system for decades if an economic crisis hadn’t hit in the 1780s. To pay off their staggering war debts—and a $3 million requisition in 1785 from the Continental Congress, which could not generate its own revenue—states enacted tax increases that fell most heavily on farmers, who made up 90 percent of the country’s population.

This devastated the economy, leading to a depression not surpassed until the 1930s. Tens of thousands of people had their farms repossessed. Jails filled with debtors. In eight states, impoverished citizens rioted. In Massachusetts, angry farmers tried to overthrow the state government. Citizens petitioned their legislatures for tax and debt relief, and politicians responded by forgoing tax collection and allowing debtors to repay their obligations with paper money instead of gold and silver coins, which were in short supply, causing massive inflation.

To the country’s economic and political elite, it appeared that the state governments were favoring the poor over the rich and debtors over creditors.

When he arrived in Philadelphia in May 1787, Madison said the “evils” of popular democracy in the states “had more perhaps than any thing else, produced this convention.” The erudite Virginian believed that majority rule was inevitable and, indeed, preferable in a democratic society. But he also worried that rash and impulsive majorities could trample minority rights and threaten the viability of self-government.

While most American citizens came from modest means, virtually all of the delegates to the Constitutional Convention owned large amounts of land, many were extremely wealthy, and nearly half were enslavers. Their views unapologetically reflected this class bias. The framers of the Constitution had no conception that white people would one day become the minority, but they were keenly aware that they themselves were a distinct minority who needed to be shielded from the masses. If a majority were to control all branches of the government, John Adams wrote, “debts would be abolished first; taxes laid heavy on the rich, and not at all on the others; and at last a downright equal division of everything be demanded, and voted.”

In 1776, the prevailing view of the founders had been that people were meant to be as close to the government as possible. Now, in order to rescue the new American experiment, Madison strove to create a system that he hoped would result in “the total exclusion of the people in their collective capacity, from any share” in governing the country.

A day after Madison spoke against the excesses of majority rule, the convention considered the Virginia Plan for a new upper house. In every state except Maryland, the upper house was elected by the people, but Randolph and Madison proposed that members of the US Senate be nominated by state legislatures and selected by the House, with no involvement from the public. They suggested that both houses of the legislature be apportioned according to the population of each state, which would insulate the new Congress from popular majorities while striving to maintain the government’s legitimacy by ensuring that it represented the greatest number of people.

But the country was narrowly split between large states and small ones. To protect their power, representatives of the smallest states argued that each state should have an equal number of senators. On June 30, Gunning Bedford Jr., the attorney general of Delaware, confronted the delegates from Massachusetts, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, the three largest states in the union. “I do not, gentlemen, trust you,” he said. “If you possess the power, the abuse of it could not be checked; and what then would prevent you from exercising it to our destruction?” He issued a startling ultimatum: “The large states dare not dissolve the Confederation. If they do, the small ones will find some foreign ally of more honor and good faith, who will take them by the hand and do them justice.”

To prevent a rebellion among the small states, the delegates narrowly agreed to their demand while maintaining proportional representation in the House of Representatives. Equal representation became known as the Great Compromise, but as Daniel and Stephen Wirls write in The Invention of the United States Senate, “The Great Concession is perhaps a more apt moniker.”

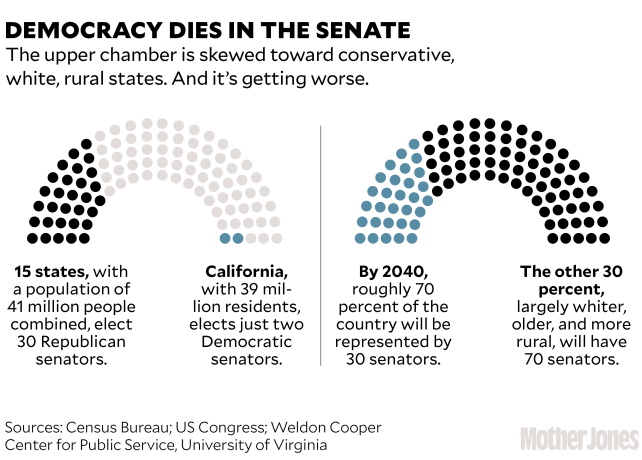

The new Senate made minority rule not just likely, but inevitable. It was another stick of dynamite strapped to the foundation of American democracy. Even those who wanted to curb the power of the masses expressed trepidation. Madison presciently warned that equal representation in the Senate would only worsen inequities over time as sparsely populated Western states joined the union, allowing “a more objectionable minority than ever” to control the federal government. But the level of inequality in the Senate today—by far the worst of any upper chamber in an advanced democracy—would have shocked even him. In 1790, the country’s most populous state, Virginia, had 12 times as many people as its least populous, Delaware. Today, California has 67 times the population of Wyoming. Fifteen small states with 41 million people combined now routinely elect 30 GOP senators; California, with 39 million residents, is represented by only two Democrats.

This imbalance is growing more lopsided: By 2040, roughly 70 percent of Americans will live in 15 states with 30 senators, while the other 30 percent—who are whiter, older, and more rural than the country as a whole—will elect 70 senators.

Adding diverse areas like the District of Columbia and Puerto Rico as new states would make the Senate more representative of the country overall, but congressional Republicans have flatly rejected this. And the underlying structure of the chamber is practically impossible to fix, because doing so would require the assent of those who benefit from its inequity. As one of the last acts of the Constitutional Convention, the framers specified that no amendment could deny a state equal representation in the Senate without that state’s consent. It’s unimaginable that any sparsely populated state would voluntarily give up this massive overrepresentation.

The composition of the Senate also significantly underrepresents voters of color. White people make up 46 percent of the population of the five most populous states but 78 percent of the five least populous states. Overall, white voters are overrepresented in the Senate by 14 percent compared with people of color.

Not surprisingly, the Senate significantly overrepresents Republicans, especially as the GOP’s advantage in smaller, whiter, rural states has become more pronounced. Senate Republicans haven’t won more votes or represented more Americans than Democrats since the 1998 election, but they’ve controlled the Senate for half the time since then.

The math is especially daunting for Democrats in 2024. Republicans can flip control of the Senate by winning Democrat-held seats in two of the nation’s least populous and whitest states—West Virginia and Montana. That would give Republicans a majority despite representing just 42 percent of the country’s population.

Even when Democrats manage to overcome the Senate’s structural bias and win a majority, the rules of the chamber make it difficult for them to govern effectively. During the Biden administration, as few as 41 Republican senators representing just 21 percent of the population have used the filibuster, which is not in the Constitution, to block legislation supported by large majorities of Americans on issues like gun control, abortion, and voting rights.

Trump’s impeachment trials vividly illustrated the skewed nature of the Senate and its implications. In 2020, the 48 senators who voted to convict him on the first article of impeachment represented 18 million more Americans than the 52 senators who voted to acquit him. When Trump was impeached again for inciting the insurrection, the 57 senators who voted to convict him represented 76.7 million more Americans than their colleagues.

But if the Senate has evolved to be an institution that protects conservative white power, the House was designed to be one. After the small states threatened to oppose the Constitution if they were not given excess power in the Senate, the slave states did the same with the House. The minority’s extortionist tactics worked a second time. To broker a deal, Scottish-born lawyer James Wilson proposed that an enslaved person be counted as three-fifths of a person, a figure that derived from how the Southern states were taxed in 1783. The near-complete acquiescence of the Northern majority was again called a compromise.

The three-fifths clause increased the Southern states’ representation in the House by one-third, greatly strengthening their power. Equal representation in the Senate and the three-fifths clause in the House warped the country’s most powerful new institution: the presidency.

When Wilson proposed that the president be directly elected by the people, the small states and the slave states contended that a popularly elected president would threaten their influence. So he floated a complicated alternative where “electors” selected by the states would choose the president.

The number of electors a state received would be equal to their total representation in both houses of Congress. This meant small states received a disproportionate number of electoral votes compared with large ones, and slave states triumphed over free ones. Virginia and Pennsylvania had roughly equal free populations at the time, Jesse Wegman writes in Let the People Pick the President, but Virginia’s 300,000 enslaved people gave the state six more House seats and presidential electors.

The North had double the free population of the South, but due to the combined weight of equal representation in the Senate, the three-fifths clause, and the Electoral College, 10 of the first 12 US presidents were enslavers, as were the speakers of the House for most of the country’s first four decades and 18 of the first 31 Supreme Court justices.

Even though electors now generally follow the will of their state’s voters, the Electoral College remains biased toward the same groups it favored at its inception, much like the US Senate. And it continues to depress voter turnout by depriving millions of citizens of a meaningful vote in presidential elections.

The structural inequities built into the Electoral College have other ripple effects. The tiny handful of battleground states are whiter and more Republican than the rest of the country. Eighty-three percent of voters in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania in the 2020 election were white, according to the New York Times, compared with 69 percent of voters elsewhere. Wisconsin, the tipping-point state in 2020, is also 3.5 points redder than the country as a whole. University of Texas political scientists estimated in 2019 that in a 50–50 popular vote election, the Republican candidate had a 65 percent chance of winning the Electoral College.

And the number of competitive swing states in 2024 is projected to be smaller than ever, comprising just six major battlegrounds (Arizona, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin) with 15 percent of the country’s population. That leaves 85 percent of Americans with little incentive to vote for the nation’s highest office, which affects down-ballot races as well.

Because representation in the Senate helps determine the number of electoral votes, smaller states also have more power than large ones to determine the president. The vote of a Wyoming resident, for instance, counts 3.7 times more than that of a Californian in a presidential election.

Like dry rot on a decaying house, the imbalances built into the electoral system keep getting worse. Things that once seemed to be an aberration, like a candidate losing the popular vote but winning the Electoral College, are now routine. Before the 2000 election, only three times in US history had the loser of the popular vote won the Electoral College. But that’s happened twice in 16 years since then. It almost occurred a third time in 2020, when Biden won the popular vote by 7 million votes but Trump lost the three closest states in the Electoral College by just 44,000 total votes. Trump never could have attempted to overturn the results—and there would have been no insurrection—if the United States had a system in which every vote mattered equally in presidential elections.

If Trump poses an existential threat to the political system, he is also a product of the flawed compromises made by the founders. The Electoral College handed him the presidency in 2016. The Senate protected him and advanced his radical agenda. The GOP’s advantages in these two branches allowed them to entrench minority rule in the third branch of government: the courts. The full conservative takeover of the Supreme Court during Trump’s presidency was the product of a bare-knuckled, decades-long strategy by Republicans. Now they’re relying on their allies on the bench to make their power irreversible.

The courts were designed to protect minority rights from the other branches of government. Alexander Hamilton wrote in the Federalist Papers that an independent judiciary was intended to “guard the Constitution and the rights of individuals” and prevent “serious oppressions of the minor party in the community.” Thurgood Marshall stated that the court’s legitimacy stemmed from its reputation as “a protector of the powerless.”

Yet, for much of our history, the courts have defended powerful minorities instead of vulnerable ones. The Supreme Court infamously upheld the institutions of slavery and Jim Crow in decisions like Dred Scott v. Sandford and Plessy v. Ferguson and sided with wealthy economic interests during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

That changed in the 1950s and ’60s. The court led by Chief Justice Earl Warren embarked on a “minority rights revolution” that embraced a broad conception of equal protection and expanded civil rights and civil liberties, from Brown v. Board of Education to the “one person, one vote” cases that established rights to publicly funded counsel, privacy, and reproductive choice.

In the 1980s, to counteract the power of this Second Reconstruction, key members of the Federalist Society deployed a new legal theory, originalism, arguing that the Constitution must be interpreted as it was understood at the time of its drafting. This aggressively reoriented the judiciary from safeguarding the rights of less powerful minorities to once again protecting the priorities of more powerful ones, such as wealthy GOP donors and partisan political interests that favor white conservatives.

The current supermajority on the Supreme Court has selectively deployed originalism to freeze the Constitution in the country’s undemocratic past, when a majority of Americans were excluded from political participation, in order to take away core rights and freedoms on issues like abortion and voting. A court constructed through a series of antidemocratic maneuvers by Republican senators like Mitch McConnell—who owe their own power to minority rule—has in turn made the country less democratic.

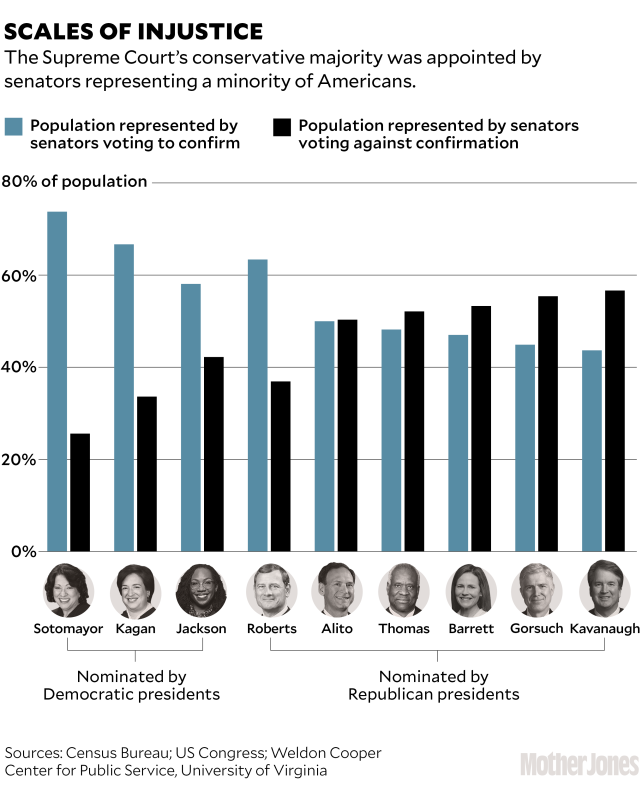

The extreme direction of the court is emblematic of how the countermajoritarian distortions in American politics have worsened. Democrats have won the popular vote in seven of the past eight presidential elections, but for the first time in US history, five of six conservative justices on the Supreme Court were appointed by Republican presidents who initially lost the popular vote and confirmed by senators elected by a minority of Americans.

Under Trump, this “superminoritarian” exception became the norm. Sixty percent of his appellate court picks were confirmed by senators elected by fewer votes or representing fewer people than the senators opposing them.

Much like Republicans in the Senate, the Supreme Court justices nominated by Trump are playing a critical role in boosting his chances of returning to the White House. The court reinstated Trump to the ballot in Colorado, Maine, and Illinois after state officials disqualified him for violating the insurrection clause of the 14th Amendment. The justices also slow-walked the question of whether Trump is immune from criminal prosecution, delaying the federal election subversion case brought by special prosecutor Jack Smith, possibly until after the 2024 election. That means Trump could face no legal accountability for his role in inciting the January 6 insurrection before voters go to the polls. It is the most brazenly political act by the court’s conservative majority since it decided Bush v. Gore, which handed George W. Bush (who also lost the popular vote) the presidency in 2000.

When the delegates adjourned the Constitutional Convention in September 1787, the final document 39 of them signed benefited small states over large ones, slave states over free ones, and the country’s wealthy over the average citizen, collectively protecting elite white power in all three branches of government. It represented a stunning counterrevolution against the principles of the revolutionary era and paved the way for oligarchy to triumph over democracy.

Some of these objections were noted at the time. “The change now proposed,” wrote the pseudonymous Federal Farmer (believed to be New York’s Melancton Smith), “is a transfer of power from the many to the few.” The new Constitution would “swallow up all us little folks,” predicted Amos Singletary, a gristmill owner from Massachusetts, “just as the whale swallowed up Jonah.” Even those who strongly supported the Virginia Plan had grave doubts about some of the concessions they were forced to make.

The Constitution, despite its notable antidemocratic features, was still a remarkable document for its time, creating a strong central government and robust system of checks and balances that became a model for democracies across the globe. It prevented the country from sliding into anarchy, set up durable governing bodies, and restored elites’ faith in democracy. Yet it remains a fundamental contradiction that the nation’s most important democratic document was intended to make the country less democratic, and that a system of government founded on principles of majority rule would create institutions that facilitated minority rule instead.

Even as the political system was slowly democratized in fits and starts following the ratification of the Constitution, the belief that popular majorities needed to be constrained rather than encouraged, and that privileged minorities should be protected over excluded ones, persisted in American politics. So many of the antidemocratic elements from 1787 stubbornly persist, partly because the Constitution is so difficult to revise, with amendments requiring two-thirds of the Congress and three-quarters of states to approve them. This makes the flaws in the Constitution self-perpetuating: The more unfair the country’s governing institutions become, the harder they are to change.

Of course, Trump is not just a creation of America’s undemocratic political foundation; he’s an active accelerant of it. He’s exploited institutions like the Electoral College, US Senate, and Supreme Court that benefit him and his MAGA coalition while pushing harder than any other previous president to dismantle the constitutional roadblocks that stand in the way of autocracy—weaponizing the 2020 census to protect a conservative white minority, trying to undermine the postal system to stop mail voting, threatening to imprison his political opponents, and even calling for the “termination” of the Constitution when his attempt to overturn the 2020 results failed.

Trump’s vow to be “a dictator” on “day one” and his larger project for the second term—mass deportations, purging the federal bureaucracy, voter suppression on steroids—are so alarming precisely because his authoritarianism, combined with the conservative takeover of the other branches of government, could make minority rule impossible to reverse. This could be the year that the compromises the founders made finally cause American democracy to crumble.