Mother Jones; El Nuevo Herald, Roberto Koltun/AP

This story was reported by Floodlight, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates the powerful interests stalling climate action.

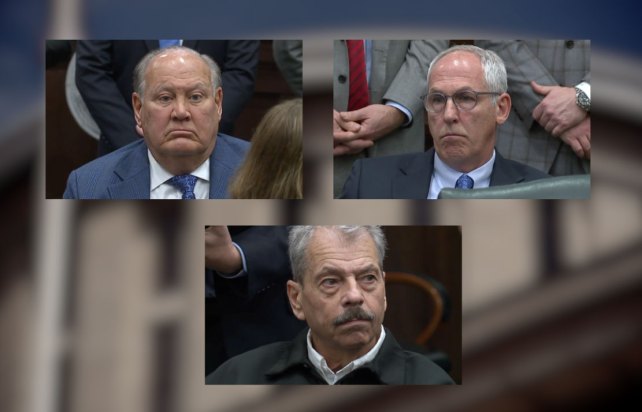

At a press conference last month, flanked by sheriffs and attorneys, Ohio Attorney General David Yost announced the indictments of two utility executives who allegedly tried to “hijack” state electricity policy for their own corrupt ends by paying $4.3 million in bribes to Sam Randazzo, then chair of the state Public Utilities Commission. The two men stand accused of trying to bilk taxpayers out of $1.2 billion on behalf of their former employer, FirstEnergy.

This was just the latest in an ongoing criminal probe of utility corruption that reached deep into the Ohio statehouse. Randazzo had been indicted previously by the Department of Justice, accused of working secretly with executives for more than a decade to secure favorable regulations for FirstEnergy—which pleaded guilty to federal fraud charges in 2021 for its role in the scandal. Last year, three lobbyists, along with former Ohio House Speaker Larry Householder, pleaded guilty to or were convicted of federal racketeering charges. (Faced with the prospect of years in prison, one of the lobbyists took his own life.) Another utility operating in Ohio, American Electric Power, is under investigation by the Securities and Exchange Commission. “Power is inherently seductive and corrosive,” noted a somber Yost, after laying out the latest alleged plot.

The Ohio scandals are no fluke. They are part of a generational resurgence of fraud and corruption in the utility sector, according to a Floodlight analysis of 30 years of corporate prosecutions and federal lawsuits. And they come at a time when trillions of dollars and the health of the planet are at stake as some power companies embrace—while others seek to block—the transition from fossil fuels to wind, solar, and battery storage.

Over the past five years, at least seven power companies have been accused of fraud or corruption. Seven industry executives have pleaded guilty or been federally indicted, along with a handful of appointed and elected officials. And a growing number of industry shareholders have sued the companies, claiming executives lied about their alleged misdeeds.

Utility fraud and corruption—in Florida, Illinois, Mississippi, Ohio, and South Carolina—have cost electricity customers at least $6.6 billion, according to Floodlight’s analysis. Ratepayers have bankrolled nuclear plants that never got built, transmission systems that were over-engineered to beef up profits, and aging coal facilities that couldn’t compete with cheaper plants powered by methane, which the industry calls natural gas.

Like waiters with a guaranteed tip, many power companies operate as state-sanctioned monopolies that collect government-guaranteed returns on their investments. The companies increase returns by building new power plants and transmission lines, and by jealously defending their turf—even if it hurts consumers and the environment.

“I’m actually flummoxed by why the [utility] CEOs and executives would revert to corruption,” said Mark Toney of the nonprofit Utility Reform Network, “when the record is, you can make so much more if you’re focused on just running the scam that it is.”

Most of the experts we interviewed attribute the increased corruption to a mix of lax regulation and a weakening of Depression-era safeguards meant to rein in rapacious monopolies. Electric companies have always aggressively hawked their profit-making agendas to state regulators—“the only real customer for the utility company,” notes Mike Jacobs, a senior energy analyst at the Union of Concerned Scientists. But lately some of those companies have been caught breaking the law in the process.

“The scariest part of this wave of utility scandals is what we don’t know: How many utilities have committed crimes that prosecutors haven’t noticed?” said David Pomerantz, executive director of the Energy and Policy Institute, a utility watchdog.

“What about schemes that didn’t break any obvious laws, but extracted more money from customers every month only to pad utility profits, without improving service?” he added. “The only way we’ll ever know the answers to these questions is if regulators crack open utilities’ books and emails and investigate.”

Former FirstEnergy executives Charles Jones (top left) and Michael Dowling (top right) and former Ohio Public Utilities Commission Chair Sam Randazzo worked together to secure favorable legislation for the utility, prosecutors say. The three are facing a slew of federal corruption charges.

Morgan Trau/WEWS/Floodlight

The last time there was this much turmoil in the electricity sector, you could still rent DVDs at Blockbuster.

Back in the early 2000s, as a wave of deregulation washed over the industry, the unscrupulous actions of gas and electricity traders—most notably Enron—contributed to a massive energy crisis in California. The companies that employed the traders gamed newly created power markets by placing fraudulent trades and, amid rolling blackouts, took power plants offline when electricity demand was highest as a way to drive up prices and enrich themselves.

The tumult reached its peak in 2002, when six industry executives were indicted for a variety of fraudulent schemes, and seven shareholder suits alleging fraud were filed against energy companies.

The issue of fraud and corruption is more critical now as the nation transitions to a cleaner energy future, and power companies project spending billions of dollars on offshore wind and nuclear power projects as they shut down older fossil fuel plants. The International Energy Agency projects that annual capital spending in the energy sector will increase from $2.8 trillion globally last year to more than $4 trillion in 2030.

But behind the scenes, utilities have resorted to a wide range of tactics to block the transition—even, in some cases, criminal behavior. “I think because of the importance of climate change, the stakes are much higher,” said Steve Cicala, an economics professor at Tufts University who studies the energy sector.

Click to see Floodlight’s interactive timeline: “Fraud & Corruption Scandals at U.S. Power Companies.”

Mother Jones; El Nuevo Herald, Roberto Koltun/AP; Wikimedia

Power companies have made some progress. US emissions overall are down roughly 17 percent from their 2007 peak as utilities shuttered coal plants in favor of gas, which burns cleaner, and renewables. But the sector has a long way to go to meet the targets set by international negotiators in the 2015 Paris agreement on climate change.

Fraud and corruption, Wall Street analysts warn, could short-circuit the transition to cleaner energy, prompting mistrust among consumers and major investors, whose support is needed to pay for the shift. “When investors see that executives have misled either consumers or regulators,” said Travis Miller of Morningstar Research Services LLC, “they get nervous about what else executives might be doing to mislead investors.”

In six lawsuits, shareholders have claimed losses of more than $12 billion over the past five years due to alleged utility fraud and corruption. So far, three companies have paid out a total of $500 million in settlements.

Brian Reil, a spokesperson for the Edison Electric Institute, the group that represents investor-owned electric utilities, said he sees no cause for concern: “Our member companies are highly regulated entities at both the federal and state levels, and in the limited instances where there has been real evidence of wrongdoing, we have relied on the proper authorities to do their work.”

Federal prosecutions of white-collar crimes of all kinds are at historic lows, and shareholder lawsuits have returned to historically average levels after peaking in 2019. Yet fraud and corruption loom large in the recent scandals.

In Ohio, officials began investigating FirstEnergy and AEP after lawmakers passed House Bill 6 in 2019. That bill gutted the state’s energy efficiency standards, bailed out FirstEnergy’s struggling nuclear plants with $1.2 billion in public funds, and propped up AEP’s coal plants with a $243 million subsidy.

FBI agents eventually discovered that FirstEnergy had secretly donated more than $60 million to groups controlled by Householder, then Ohio’s House speaker, in exchange for passing the bill. The company pleaded guilty in 2021 and has been cooperating with investigators.

Court records also show that AEP, which has not been charged, donated at least $500,000 to a Householder-related group. Householder was sentenced last year to 20 years in federal prison. He is appealing the ruling, claiming the bribe payments fall within his First Amendment rights.

Former Jacksonville Electric Authority executives Aaron Zahn (left) and Ryan Wannemacher are on trial for conspiracy and wire fraud for their role in the attempted sale of the utility in 2018. They face up to 25 years in federal prison if convicted.

Florida Times-Union via Floodlight

In Illinois, Commonwealth Edison admitted in 2020 to bribing Mike Madigan, Illinois’ longest serving House speaker, with no-show jobs for his political supporters. In exchange, prosecutors say, Madigan helped the utility get at least two favorable bills through the state legislature, and one unfavorable bill killed—benefits the SEC says totaled more than $150 million.

The new laws allow Commonwealth Edison to spend extravagantly—some say unnecessarily. “We’re going to be paying for 10 years of gold plating [transmission lines] that came out of a corruptly passed law for years to come,” said Sarah Moskowitz, executive director of the state’s Citizens Utility Board.

Two Commonwealth Edison executives pleaded guilty last May. Madigan’s federal trial is set for October. The company has paid more than $450 million in fines and settlements arising from the scandal.

In Florida, two executives of the Jacksonville Electric Authority are on trial on charges of wire fraud after the pair were caught crafting a golden parachute that would pay them “exorbitant funds” upon the sale of the municipal utility to a private company.

The likely buyer? Palm Beach County–based NextEra Energy, which shareholders accused in a lawsuit of lying about a job offer its consultants arranged for a Jacksonville city commissioner who was a presumptive “no” vote on the sale.

The suit also claims the same consultants deployed hundreds of thousands of dollars in dark money to support third-party “ghost” candidates in four state Senate elections at the behest of the power company. NextEra disputes the allegations and has filed a motion to dismiss the suit.

A Mississippi whistleblower, meanwhile, filed a lawsuit that accuses Southern Co. of stealing $382 million from the federal government during a failed $7.5 billion attempt to build a coal gasification plant there. The company already paid another whistleblower an undisclosed amount in 2016, and settled a related shareholder suit for $87.5 million in 2020.

And in South Carolina, the former CEO of SCANA Corp. was sentenced in 2021 to two years in federal prison for defrauding ratepayers during the failed construction of a nuclear reactor. The debacle cost the ratepayers $3.8 billion.

More than a century ago, privately owned utilities helped create today’s regulatory system, in which appointed or elected commissions review utility expenditures and proposed rate increases in exchange for granting the companies monopoly status. The utilities pushed for state-level regulation as they sought ways around irregular local rules.

By the 1920s, according to Virginia Tech technology historian Richard Hirsh, the industry had grown effective at capturing and manipulating its regulators, leading to decisions that put the utilities’ bottom lines ahead of the public interest. And the majority of the industry’s assets were concentrated in the hands of a few highly leveraged holding companies. “So the Federal Trade Commission in 1928, through about 1933 or so, pursued these investigations of utility companies and uncovered some of these abuses and made them public,” Hirsch said.

The FTC investigations culminated in the 1935 passage of the Public Utility Holding Company Act, a core plank of Roosevelt’s New Deal. The act splintered the holding companies and gave the federal government more control of the industry.

Florida Power & Light’s nuclear reactors at Turkey Point stand on the Biscayne Bay in Miami-Dade County. Shareholders have accused FPL’s parent, NextEra Energy Inc., of hiring consultants to support third-party “ghost” candidates in four state Senate races.

Mario Alejandro Ariza/Floodlight

The establishment of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission in 1977 led to further transparency. The agency required utilities to file yearly expenditure reports in which they disclosed political giving and lobbying and contractor relationships. That line-by-line reporting stopped in 2002, as FERC switched from paper to digital records.

In 2005, Congress undid other core provisions of the public utilities law, allowing holding companies to re-consolidate their markets and their political power. The Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United, which helped pave the way for unrestricted, untraceable spending in the political arena, only made it easier for utilities to thwart clean-energy efforts.

“The repeal of PUHCA is definitely a major contributing factor to some of the problems we’re seeing today,” said Tyson Slocum, director of Public Citizen’s Energy Program. “It turns out that the lessons that Congress learned during the Great Depression and the collapse of the market, the collapse of many of our economic systems, were proven right.”