When Ethan Block heard that Andy Kim was running for Senate, he got to work. Over winter break, the Rutgers University senior launched a campus group to spread the word about the low-profile congressman taking on Bob Menendez, the longtime Democratic senator who’d just been indicted for allegedly accepting bribes of gold bars and cash-stuffed envelopes. By February, Block’s new group—RU For Andy—boasted a roster of about 40 students volunteering to take part in canvassing and voter education.

To Block, Kim wasn’t just battling one disgraced incumbent—he was also challenging the iron grip of New Jersey’s political ruling class, which, having finally been forced to abandon Menendez, had now thrown its weight behind a candidate from its own ranks: the governor’s wife. Although Tammy Murphy trailed Kim by double digits in the polls, she was crowned the presumptive frontrunner almost as soon as she entered the race.

But swapping an indicted politician for the first lady, Block argues, just felt like “replacing corruption for nepotism.” And “we’re not looking for either one of those things.”

At first, Kim probably wouldn’t strike most people as the kind of candidate who would energize young voters like Block. The 41-year-old, three-term congressman from South Jersey casts himself as a humble civil servant who believes in “customer service governance.” He famously cleaned up trash in the Rotunda after rioters stormed the Capitol. He speaks about filibuster reform and prescription drug affordability. He’s unafraid of cringey political cliches: “I’m a workhorse, not a show horse,” is a campaign mantra.

Throughout his political career, Kim has been a pretty mainstream Democrat. For years, he served as a national security staffer in the Obama White House. He flipped his pro-Trump House district in 2018 by defending Obamacare, but he stopped short of embracing Medicare for All. He’s in the Congressional Progressive Caucus, but as many of his fellow members were pushing for the Green New Deal, Kim considered the legislation a “pie in the sky.” Recently, amid a growing outcry against the war in Gaza, Kim has called on lawmakers to send more humanitarian aid but hasn’t signed on to resolutions demanding a ceasefire.

Yet Kim has become a rising star among many young voters, who say his campaign does in fact pose a radical vision: that a relative outsider—or at least someone not fully enmeshed in New Jersey’s infamous political machines—could triumph over the system that’s long dominated the state. As their generation stares down existential threats like climate change and gun violence, many argue, the status quo has simply allowed leaders like Menendez to enrich and empower themselves. But if Kim can somehow prevail, then maybe he can help usher in a fairer, more democratic system that will finally put voters first.

“As a New Jerseyan, we’re used to having the party leaders just, like, choose our next senator,” says V Matthew Steinbaum, a 21-year-old student at Northwestern University who hails from New Jersey. But Kim can “break that system,” he believes. “He’s going around showing that it is possible for our state to have someone who is chosen by the people.”

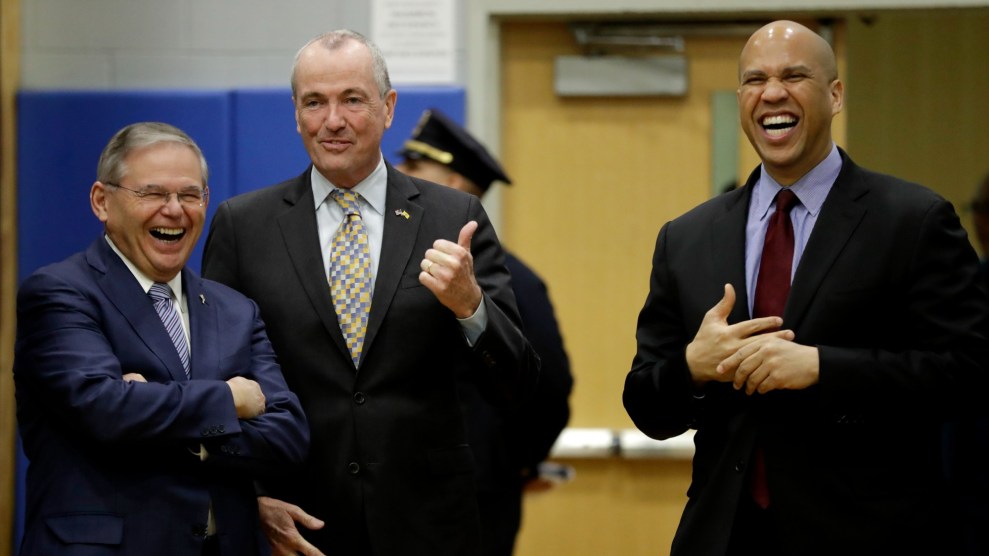

New Jersey’s reputation for corruption and backroom dealing is well deserved. This isn’t even the first set of criminal charges for Menendez, who was indicted for corruption once before, in 2015. But after that case ended in a mistrial, practically every top Democrat in New Jersey fell in line to prop up his 2018 reelection bid, including fellow Sen. Cory Booker and then-governor-elect Phil Murphy, whose wife is now running against Kim for the seat. With their hearty endorsements, Menendez sailed back into the Senate for a third term.

Strong party endorsements offer an outsized electoral advantage in New Jersey’s primaries. Nineteen of the state’s 21 counties design their ballots in an extraordinarily confusing way that tips the scales toward local bigwigs’ favorite candidates. On ballot sheets, party bosses can put their top picks on the county line—a list of candidates endorsed for all seats currently up for election, from county clerk all the way to the presidency. Challengers who lack the bosses’ favor are often kicked to “ballot Siberia,” where they are likely to be ignored by voters.

When Murphy announced her bid in November, it seemed like the machine was churning as usual. Despite never having held elected office—she started out at Goldman Sachs before marrying Phil and taking up board seats at schools and nonprofits—and being a registered Republican until 2014, the first lady quickly locked up dozens of endorsements from state and local Democratic leaders. Come primary day in June, it’s likely that many New Jerseyans will see her name on the coveted county line.

For many young voters, the influence of party bosses has long sucked the oxygen out of elections, making it difficult for them to fight for the changes they desperately want.

Aidan DiMarco, a Rowan University freshman, recalled this frustration when canvassing for a progressive newcomer in his district challenging Rep. Donald Norcross, then a four-term Democratic congressman and brother of one of New Jersey’s biggest power brokers. For DiMarco, this was a chance to elect someone who backed the Green New Deal—or at to least crank up the pressure on other lawmakers. “My generation can’t afford to ignore the climate crisis,” he explains. But he watched in disappointment as top Democrats lined up behind the incumbent as usual.

“We don’t really have an opportunity to elect people who we see more eye-to-eye with,” says Ryan True, a sophomore at Rowan. Many leaders in New Jersey “are not really liberal, they’re just moderate Democrats or even left-leaning Republicans who just won under the name of Democrat, and they get elected despite any of their challengers,” says True. “And it’s impossible to get more progressive candidates into office.”

Kim has made ballot reform a key part of his platform. “We don’t see a fair process when it comes to this Senate race,” he said in a debate against Murphy in February. New Jersey, he argued, should join the ranks of every other state and abolish the county line.

The Murphy team shot back. “Congressman Kim has also happily ran on county lines with party support in every single election he’s ever run in,” a spokesperson told Politico. Kim “seems to be of the opinion that when he receives a county line it’s OK, but when someone else does, it’s not.”

In early February, Kim secured a resounding victory in the state’s first county convention in Monmouth, granting him a spot on the line on Murphy’s home turf. He’s since defeated Murphy in two more conventions. Even so, last week he sued the state’s counties—including the counties whose conventions he’d won—in an effort to get a federal judge to bar the use of county lines.

Aside from the ballot issue, Kim also brings a new vision for cleaning up New Jersey politics in general, argues Nate Howard, a junior at Princeton University.

Howard points to a recent controversy that sparked outrage among many young voters in the state: In January, the New Jersey College Democrats was gearing up to endorse Kim when they received a series of alarming calls from someone connected to the Murphy team, warning them that the move could hurt members’ job prospects. The caller, also a college student, told the New York Times that while she wasn’t asked to pressure the group, some of Murphy’s staff had “wanted to do something to prevent the endorsement.”

It backfired. The College Democrats of America and its New Jersey chapter came out with a ringing endorsement of Kim. A Murphy spokesperson later denied any campaign involvement, telling the Times that the comments “were made by a young person with no connection to our campaign.” The student caller, who worked part-time for the Democratic State Committee, said to the Times she was receiving texts from a Murphy campaign consultant and wanted to alert students to the possible fallout of a Kim endorsement.

But for Howard, who was on one of the calls, the incident exemplified the “kind of dirty machine tactics” that has long throttled the democratic process in New Jersey. “This was exactly why we needed Andy Kim,” he says, so that “there won’t be these types of calls that happen where people are threatened.”

It was “everything that Andy Kim is running against,” says Block. “That we have to play it like it’s House of Cards. That’s not what politics should be.”

Still, other Gen Z voters are skeptical about whether Kim represents a change at all. The congressman’s reluctance to call for a ceasefire in Gaza shows that “he definitely is not as progressive as he advertises himself to be,” argues Gabi Green, a student at Brookdale Community College. “It’s just going to be more of the same crap of just having another blue politician in a blue state.”

On Gaza, Kim has supported a “mutually-agreed upon ceasefire” but has disagreed with calls to halt the fighting while Hamas still holds Israeli hostages captive. For 21-year-old Green, this stance has pushed her towards more left-leaning challengers, like activist Larry Hamm.

Murphy, for her part, has remained vague about her position on Gaza, even raising a questionable theory about the war’s origins: “‘In my opinion,'” she told New York magazine, “‘there’s about four really bad actors in the world’—Iran, Russia, China, and North Korea—‘and this whole thing was instigated as a proxy war in order to distract the West, in order to make sure we weren’t able to focus on Ukraine.’”

With the outcome of Kim’s ballot lawsuit unclear, Murphy’s roster of powerful supporters could still prove pivotal in the race. But at least it’s closer to a real competition, says True. And if that forces candidates to work harder for the youth vote, it’ll be a first step towards “seeing candidates who better represent our ideologies, who better represent the future.”