Eric Gay/AP

The foundation behind the National Book Awards, one of the most prestigious literary prizes in the United States, announced on Thursday that it will no longer restrict prizes to authors who are US citizens, expanding eligibility to non-citizens and other longtime residents.

The change will affect prizes for fiction, nonfiction, poetry, and young people’s literature to begin including authors “who maintain their primary, long-term home in the United States, US territories, or Tribal lands” regardless of their citizenship status. The updated eligibility criteria officially sunsets the petition process that was introduced in 2018 to include non-citizen authors but was ultimately criticized as onerous.

“We believe in the value of all stories, and it is our hope that by further opening our existing submissions process, the National Book Awards will be more reflective of the US literary landscape and better able to recognize the immense literary contributions of authors that consider the United States their home,” said David Steinberger, Chair of the Board of Directors of the National Book Foundation, in a public statement.

The new policy, which will go into effect next month when the 2024 awards cycle begins, is part of a broader sea change led largely by undocumented authors that seeks to reassert the importance of the immigrant story in the American literary canon. Javier Zamora, author of the New York Times bestseller Solito, is one of those authors. I spoke to Zamora last September after the Pulitzer Prize board announced its decision to drop citizenship requirements for its books, drama, and music awards.

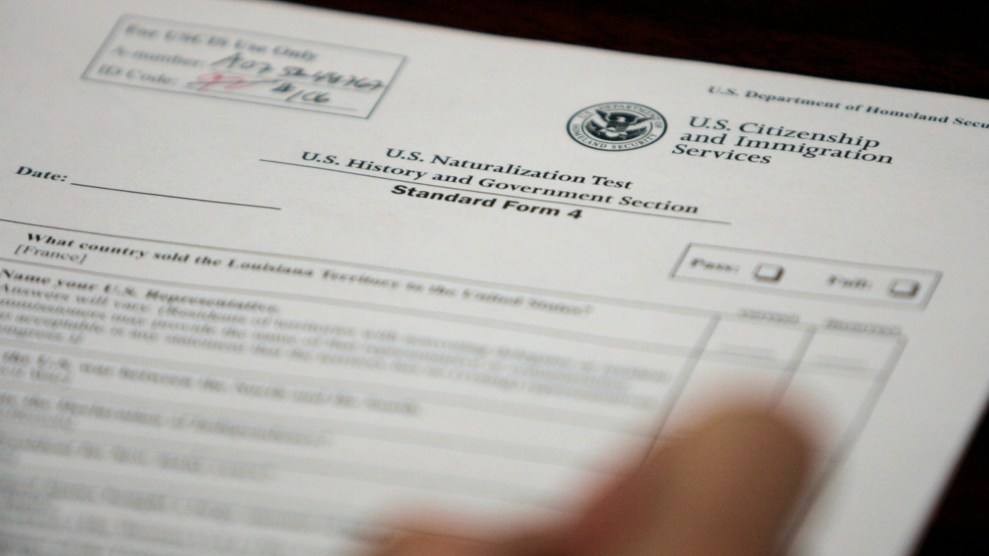

Though Zamora emphasized that the Pulitzer Prizes and the National Book Awards are not the worst offenders in the US’s immigration policies—”We have Homeland Security and Congress for that,” he told me—the awards’ embrace of the idea that citizenship is a prerequisite to making great American art limited both our imaginations and understanding of the American story.

“What [these groups] lack is the understanding that ‘American’ means everybody,” Zamora said. “It means everybody who wants and believes in a safe world, freedom, liberty, and justice—for all. If I am fleeing a country because of my sexual identity, gender, identity, or because I don’t feel safe, I have the right to obtain liberty and justice. That’s what the United States is all about.”

The National Book Foundation’s decision comes against the backdrop of seemingly relentless headlines declaring a crisis at the border and US immigration policies that are hostile to migrants and asylum seekers. “Artist organizations have an opportunity to show the rest of the country how to imagine a world where everybody is included,” Zamora told me in September. If our political climate on immigration is any indication, we need those stories and that world now more than ever.