Vito Ansaldi

It’s been a hell of a year for science scandals. In July, Stanford University president Marc Tessier-Lavigne, a prominent neuroscientist, announced he would step down after an investigation, prompted by reporting by the Stanford Daily, found that members of his lab had manipulated data or engaged in “deficient scientific practices” in five academic papers on which he’d been the principal author. A month beforehand, internet sleuths publicly accused Harvard professor Francesca Gino—a behavioral scientist studying, among other things, dishonesty—of fraudulently altering data in several papers. (Gino has denied allegations of misconduct.) And the month before, Nobel Prize–winner Gregg Semenza, a professor at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, had his seventh paper retracted for “multiple image irregularities.”

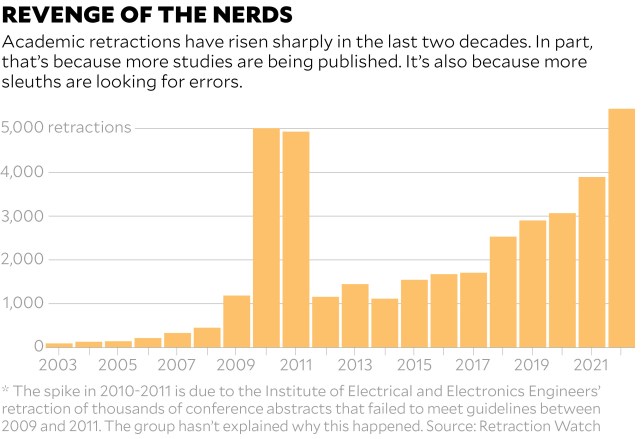

Those are just the high-profile examples. Last year, more than 5,000 papers were retracted, with just as many projected for 2023, according to Ivan Oransky, a co-founder of Retraction Watch, a website that hosts a database for academic retractions. In 2002, that number was less than 150. Over the last two decades, even as the overall number of studies published has risen dramatically, the rate of retraction has actually eclipsed the rate of publication.

Retractions, which can happen for a variety of reasons, including falsification of data, plagiarism, bad methodology, or other errors, aren’t necessarily a modern phenomenon: As Oransky wrote for Nature last year, the oldest retraction in their database is from 1756, a critique of Benjamin Franklin’s research on electricity. But in the digital age, whistleblowers have better technology to investigate and expose misconduct. “We have better tools and greater awareness,” says Daniel Kulp, chair of the UK-based Committee on Publication Ethics. “There are in some sense more people looking with that critical mindset.” (It’s a bit like how in the United States, the rise of cancer diagnoses in the last two decades may in part be attributable to better, earlier cancer screenings.)

In fact, experts say there should probably be more retractions: A 2009 meta-analysis of 18 surveys of scientists, for instance, found that about 2 percent of respondents admitted to having “fabricated, falsified, or modified data or results at least once,” the authors write, with slightly more than 33 percent admitting to “other questionable research practices.” Surveys like these have led the Retraction Watch team to estimate that 1 out of 50 papers ought to be retracted on ethical grounds or for error. Currently, less than 1 out of 1,000 get removed. (And if it seems like behavioral research and neuroscience are particularly retraction-prone fields, that’s likely because journalists tend to focus on those cases, Oransky says; “Every field has problematic research,” he adds.)

The trouble is, authors, universities, and academic journals have little incentive to identify their own errors. So retractions, if they do happen, can take years. “Publishers typically respond to fraud allegations like molasses,” says Eugenie Reich, a Boston-based lawyer who specializes in representing academic whistleblowers. In part, that’s because of legal liability. If a journal publishes a correction or a retraction, Reich notes, academics whose work is called into question may sue (or threaten to do so) over the hit to their reputation, whereas whistleblowers who flag an error are unlikely to sue journals for taking no action. Harvard’s Gino, for instance, sued the university and her accusers in August for at least $25 million for defamation.

Still, with thousands of retractions per year, it’s clear the scientific record could use some scouring. One potential solution, Oransky suggests in Nature, is to reward and incentivize sleuths for identifying misconduct, much like how tech companies (and the Pentagon, apparently) pay “bug bounties” to people who find errors in their code. Boris Barbour, a neuroscientist and co-organizer with PubPeer, a popular website for discussing academic papers, also notes that it’d help if authors or journals published the raw data supporting a paper’s findings—something funders of the research could mandate—to allow for more transparency and accountability. (The National Science Foundation, a major federal funder of research in the United States, plans to start requiring public access to datasets sometime in 2025, a spokesperson told me, in response to a White House memo last year.) “It will be harder to cheat, easier to detect. Science would just be higher quality,” Barbour says.

Oransky suggests going even deeper, and addressing why people are moved to cheat in the first place. In science, it’s too often “publish or perish,” he says, employing a phrase that dates back to the 1930s. “The problem is just how much of academic prestige, career advancement, funding, all of those things are wrapped up in publications, particularly in certain journals. That’s at the core of all of it.” Or, as Reich put it, “When you incentivize people to publish, but you have essentially no consequences for fraudulent publication—that’s a problem.” To incentivize honest research, Kulp suggests encouraging journals to accept and publish studies that show a lack of results—failures, essentially. In biomedical research, for instance, an estimated half of clinical trial results never get printed, according to the Center for Biomedical Research Transparency, a not-for-profit organization that is working to encourage the publication of “null” results—when a treatment is not effective—in journals like Neurology, Circulation, and Stroke.

And that’s the irony of all this. In science, we’re taught mistakes are essential. Without failure, there’s no progress. If journals, universities, and scholars—beginning with those in our most prestigious labs—stopped hiding from error and embraced it, we’d all be better for it.