The Campbell County Public Library is a handsome, low-slung building in the center of the small city of Gillette, Wyoming. Steps lead up to two sturdy stone columns that support an overhang, where patrons can sit on benches protected from the summer’s baking sun or the winter’s driving prairie snow. A tidy garden of wildflowers blooms to the side of the building, punctuated with life-size statues of old-timey cowboys and their horses. Out front is another statue: a pigtailed little girl with a joyful expression, sitting atop a globe perched on a stack of books. According to a plaque in front of it, the sculpture, created by an artist named Gregory Johnson and purchased in 2015 by the Mayor’s Art Council, is called “Cabin Fever.”

On the hot August afternoon when I visited, it was hard to imagine that anyone, even a girl statue, could feel a hint of cabin fever in a place like Gillette. The big sky was a bracing blue, with a few slow-moving piles of downy clouds. Parents greeted each other like old friends while their young children hopped around on the steps. In addition to housing two sprawling floors of books, the library serves as a gathering place: There are playtimes and story hours for kids, clubs and a makerspace for teens, and book groups and author talks, and musical performances for adults.

Inside, a graying crowd of about 50 people filed into a roomy event space for the monthly library board meeting. Together we set up folding chairs in rows with an aisle down the middle. Once the Pledge of Allegiance had been recited and God’s grace had been requested, the five board members seated at a curved table in the front of the room called the meeting to order. A woman with a gray-blond bob and a no-nonsense demeanor, whom I later learned was library board chair Sage Bear, addressed the room.

“I propose that since there are some discrepancies on what a sex act is, we add some of this verbiage,” Bear said. She began reading from a paper in front of her. “It says the term ‘sex act’ or ‘sexual activity’ means any sexual contact between two or more persons, by any of the following: penetration of the penis into the vagina or anus, contact between the genitals or mouth and anus, contact of the genitalia of one and the genitalia or anus of another…” She went on for another minute or so, listing other potential scenarios one might encounter while reading books, until she got to “the touching of a person’s own genitalia or anus with finger hand or artificial sexual organ or similar device at the direction of another person.” Bear paused and looked up. “I think we should add that to our definition.”

The other four members of the board nodded and took notes studiously as if Bear were talking about the mundane library meeting agenda items—the budget for computers, say, or a new coat of paint for the restroom—instead of the variety of specific sex acts that she considered too lewd for the young adult section.

Part of the children’s room at the Campbell County Public Library

Kiera Butler

The monthly library board meetings haven’t always been so X-rated. Until two years ago, they were so tedious that hardly anyone besides the appointed board members bothered to show up, easily fitting in one of the library’s cozy study rooms. But all that changed in June 2021 when a fight over one of the library’s Facebook posts about its gay pride display led to a real-life shouting match during meetings, which, in turn, led to more shouting matches over a transgender magician who was scheduled to perform in the children’s room. Some residents were concerned that such library events were a covert effort to corrupt the youth. They’d heard about drag queen story hours in other parts of the country.

Within a matter of months, so many people crammed into the study room, the board had to move the meetings into the library’s main event space. As attendance swelled, certain conventions emerged. The aisle separating the chairs turned out to be both practical and symbolic—the crowd divided itself along political lines. Those who accused the library of corrupting the youth sat to the right of the center aisle, and those who defended the collection were on the left.

In April 2022, the battle in Gillette collided with a conservative uproar over the American Library Association, the professional organization that offers grants, support, and training to its 50,000 members, mostly librarians. That month, the group’s newly elected director, Emily Drabinski, tweeted, “I just cannot believe that a Marxist lesbian who believes that collective power is possible to build and can be wielded for a better world is the president-elect.” For conservative outlets her tweet provided proof of the organization’s political agenda. Breitbart called it a “Dewey decimal disaster.”

The State Freedom Caucus Network, an arch-conservative alliance of state legislators, called for their state library organizations to break from the ALA. Texas, Missouri, and Montana have done so, though the move has been largely performative since individual libraries can still keep their affiliation. Montana lawmakers justified the move by claiming their state constitution “forbids association with an organization led by a Marxist.” But even as other states may have asserted displeasure with the organization, in October 2022, the Campbell County Public Library became the first in the nation to officially break ties with the American Library Association, accusing the organization of Marxist indoctrination of their children.

Nine months later, the library board fired the long-time executive director, Terri Lesley, who had held the position for 11 of the 27 years she worked there. Her offense? She refused to comply with the board’s orders to move certain books about sex-ed and LGBTQ identity from the children’s collection to the adult section, without putting the books through the official review process. Those directives were in part guided by the teachings of a Florida-based Christian group.

I had heard about the tensions in Gillette and wanted to see how the contents of a public library’s children’s collection managed to galvanize conflict in an entire town. What I discovered was a place that has always been obsessed with its children—but in recent years, what had been a wholesome project of creating a happy and caring community for families has taken a much darker turn. The idea of protecting children animates much of American life. What does that mean when that same impulse drives the culture war?

After the library board meeting—where nothing was settled—I flagged down Ben Decker, a slight 43-year-old bachelor with a bushy red beard. “Why,” I ventured, “is this issue so important to you?”

“Well, I guess looking into it further, it’s really an issue of, do we want our entire society to collapse?” he said slowly. “That’s basically what it comes down to.”

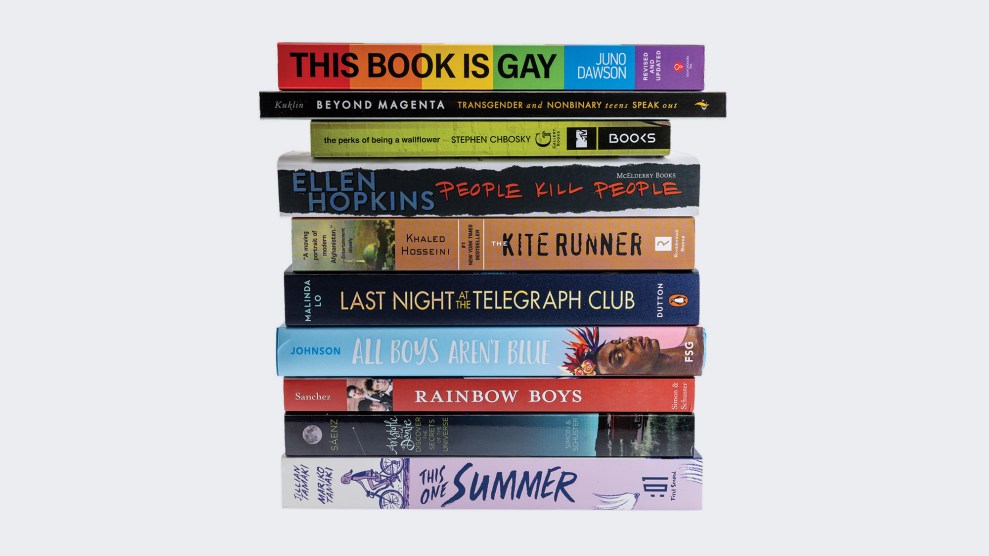

A bookshelf in the young adult room at the Campbell County Public Library.

Kiera Butler

For anyone outside Wyoming, there’s no easy way to get to Gillette, a city of 33,000 in the state’s northeast corner. From the airport in Rapid City, South Dakota, I drove my rental car two hours across the plains, past ranches, oil derricks, bobbing hydraulic fracturing pumps, and clusters of cottonwoods and box elders. I arrived in Gillette’s downtown strip of mom-and-pop stores just after school had let out for the day, and groups of kids wandered into the bakery and the ice cream store. Banners affixed to the streetlamps boasted that the town had hosted the 75th annual National High School Finals Rodeo competition. The track team from the junior high school ran past, lanky tweens in shorts and sneakers.

On its surface, the fight in Gillette may appear to be over a few books at a small-town library, but really it’s about an issue with much higher stakes, and it’s preoccupying communities from Florida to Washington State: how best to protect kids in an increasingly volatile and rancorous world. Out of the tumult of the pandemic, America’s conservative parent groups like Florida-based Moms for Liberty emerged to accuse schools of “indoctrinating” children with curriculum about systemic racism and queer identity. With the help of powerful conservative organizations, and substantial political influence, the “parents’ rights” movement remade school boards nationwide to align with their values. Moms for Liberty claims that more than half of the candidates they endorsed won their races. Part of the movement’s agenda is a crusade against books that they consider inappropriate—and in this, too, they’ve been successful. In a report last year, the reading advocacy group PEN America documented a record 2,500 book bans in the 2021–2022 school year.

Gillette doesn’t have a chapter of Moms for Liberty, but their influence is nonetheless evident. The library protesters carry signs to demonstrations saying “Stop Indoctrinating Our Kids” and “Campbell County Public Library Knowingly Encourages Sex for Minors.” Last year, Ben Decker, the activist I spoke with after the meeting, wrote in a blog post, “Libraries have changed drastically in recent decades. The worst possible people are running them. It’s time to put normal people back in charge and stop the assault on children.”

To understand Gillette, I was told, I had to talk to Charlie Anderson, a current library board member, former city attorney, and all-around man about town. I met Anderson and his wife, Teri, at the Railyard, a bar and grill where the downtown strip dead ends at the railroad tracks, and freight trains weighed down by coal rumble by. Dressed in a yellow polo shirt and a straw fedora, Anderson was as garrulous as his wife was reserved, and both of them projected grandparently warmth. Originally from Chicago, the couple moved to Gillette after Charlie’s law school graduation from the University of Wyoming in 1975. When his classmates learned he had taken a job in Gillette, he recalled, chuckling, “They said, ‘We’re gonna throw a wake for you, Charlie, this is just terrible. Maybe someday, you could be a real lawyer someplace.’” At the time, Gillette was little more than a blip on an endless stretch of I-90 with harsh weather and long-neglected infrastructure, a town-sized bachelor pad. Its main claim to fame was its water, known for coming out of the tap an unsettling shade of red.

But Gillette turned out to be an excellent place for a young lawyer. The same year that the Andersons moved there, an old Sierra Club injunction against coal mining expired, and the energy money began pouring in. With the help of a visionary mayor, Anderson and a small group of civic-minded upstarts set about channeling the influx of cash for town improvements. Within a decade, the streets were all paved, the sewer system was fully functional, the water finally ran clear, and the schools were upgraded. And money kept rolling in.

By this point, the Andersons had three kids, and they wanted to make Gillette the kind of place that attracted young families. The county commissioners built an Olympic-sized swimming pool, and a mall that housed a branch of the Campbell County Public Library and a medical clinic. The main library that I visited was built in 1983, and then the town leaders set about renovating the two high schools and the community college. In 2004, the Arts Council began commissioning local artists to make Western-themed statues. Today, around town, you might see a bronze cowboy or a family of cast iron bears by a busy intersection. You could picture a child going on a scavenger hunt to find all of them.

A sculpture in downtown Gillette, Wyoming

Kiera Butler

A sculpture outside the Campbell County Public Library

Kiera Butler

When Anderson recommended I check out the rec center, I nodded politely but privately planned to skip it, unconvinced that a few treadmills and a basketball court were worth my time. But after a few more people mentioned it, I went and instantly understood what all the fuss was about. Inside the sprawling $52 million cement building built in 2010 is a column-shaped climbing feature, a miniature version of the nearby Devils Tower National Monument is surrounded by two floors of tracks, basketball courts for the kids’ league, and gathering places. The pool area includes a small water park, with three-story slides and a lazy river, and an adjoining party room for birthdays. There are squash and racquetball courts, steam rooms, saunas, two tanning beds, and a kids’ zone with babysitting services.

Gillette youths who feel that they have exhausted all of those activities can make their way over to the 1,000-acre Cam-Plex, which houses a regulation ice rink, tennis courts, rodeo grounds, a concert venue, a campground, an RV park, and a stadium for the town’s very own professional indoor football team, the Mustangs. After local kids graduate from high school, they can attend the community college, which offers 31 degree programs. Most of its campus was renovated within the last decade—with a new student housing complex, a dining hall, and a state-of-the-art nursing simulation center.

All this is possible because nearly a third of US coal comes from Campbell County. This year, the county’s value was assessed at $5.7 billion, an especially hefty sum considering that it is home to less than 50,000 people. The worldwide push toward renewable energy may soon turn off the cash spigot, but it hasn’t yet. “We’ve had good schools, we’ve had good amenities,” Anderson told me. “It’s been good for people.”

Not that everyone in Gillette always agreed on the finer points of the budget, but the town’s leaders were united in their goal: using the wealth to enrich the lives of citizens. Jonathan Gallardo, a reporter and editor with the Gillette News Record, recalled that after the 2016 presidential election, when the rest of the country began to cleave into factions, the people of Gillette remained a beacon of small-town neighborliness where nearly everyone seemed to be on the same political page: 87 percent of residents voted for Trump.

This might explain why no one seemed to remember exactly when political acrimony began. Some people told me it was during the tumultuous early days of the pandemic when local businesses and schools closed for six weeks. Charlie Anderson suspected it was July 2020, when local young people organized a Black Lives Matter rally after the murder of George Floyd, and counterprotesters showed up in trucks, some of them flying Confederate flags.

But most everyone agreed that the library drama started with a single July 2021 Facebook post, in which a county commissioner expressed disapproval of the gay pride month display the library had put up. Soon a dozen or so people signed up to speak at the Board of Commissioners meeting, in a radical departure where the five elected commissioners usually skipped the public comment sessions because of lack of interest. This time comments lasted for more than an hour. “Parents should be informed of the queer agenda the library is implementing,” said one attendee. Another railed against the idea of a pride display in the library. “If we’re not encouraging heterosexuality among teenagers for a month in the public library,” he said, “we definitely should not be doing that with sexual identities that are known to cause things like suicide and HIV.” A stern-looking woman thundered against the young adult room. “I know about their dark basement for the teens, and enough is enough,” she said. Later that month, a local pastor posted on Facebook that he had discovered that the magician who was scheduled to perform at the library was transgender. The magician canceled her show after reportedly receiving threats.

All that fall and winter, the same crowd from the commissioners’ meeting began packing the library board meetings. In October, a local couple named Hugh and Susan Bennett filed a complaint with the sheriff’s office, requesting that the Campbell County librarians face criminal charges for stocking the shelves with books about sex education and LGBTQ identity. When a local prosecutor declined to do so, Hugh Bennett told the Associated Press, “We had thought that they would see a problem with recruiting children for sexual activity when they’re not mature enough for that to be an issue in their lives.”

The conservative activists who spoke at meetings claimed that their views were representative of Campbell County as a whole and that a small group of strident progressives had silenced them. “That [liberal] vocal minority has carried weight for years now,” one activist told Gallardo, “and they’re surprised when the silent majority actually gets a voice.”

Some Gillette residents began to wonder if the new movement was even local at all. There were rumors that the library’s antagonists had joined forces with a national group called MassResistance, which describes itself as a “leading pro-family activist organization,” but was designated a hate group by the Southern Poverty Law Center in 2010. Founded in Massachusetts in 1995, MassResistance is known for its no-holds-barred approach to anti-gay activism. The group’s founder, Brian Camenker, has compared LGBTQ advocates in schools to Nazis and celebrated Nigeria’s outlawing of homosexuality. In 2017, MassResistance published a book called The Health Hazards of Homosexuality. In 2018, the group was part of a successful effort to convince a California assemblyman to withdraw a bill he had sponsored that would have outlawed gay-to-straight conversion therapy.

According to MassResistance, the driving force behind that victory was its California director, Arthur Schaper, whose anti-immigrant activism is so extreme—he regularly thunders against “illegal aliens” at public meetings, once referred to supporters of sanctuary cities as “brown Nazis,” and welcomed a well-known white nationalist into his MassResistance chapter—that the Los Angeles County Republican Party has disavowed him.

In October 2021, Kevin Bennett, whose parents, Hugh and Susan, had advocated for the criminal prosecution of the local librarians, announced on conspiracy theorist Alex Jones’ show Infowars that he and likeminded Gillette citizens had indeed formed a local chapter of MassResistance. In November 2021, Arthur Schaper tweeted an article from the Gillette News Record about the protests at the library board meeting. “Wyoming MassResistance is making the difference,” he wrote, “and our national organization received great press and support at this time.”

When I asked Ben Decker about MassResistance, he brushed it off. “We don’t really have members,” he said, although he acknowledged that he had started the Wyoming MassResistance Facebook page, which has a few hundred followers. “It wasn’t really anything formal,” he explained. “It was like a place where we can get our ideas together.” Maybe, he allowed, the group had held a few meetings, with Arthur Schaper Zooming in from California.

Not everyone who spoke at the library board meetings supported MassResistance. When Jenny Sorenson, an English teacher at a local junior high school, heard that librarians were being accused of sexualizing children, it sounded like the rantings of a few extremists. She was confident that more moderate voices in the community would eventually prevail. “Well, fast forward a year,” she told me. “It hadn’t died down.” When she finally found the time to attend a board meeting, she was floored. “I heard the public comments, and how hateful they were to our LGBTQ community and our librarians; calling the librarians, pedophiles, and groomers, saying that if you read a book you’ll get an STD,” she recalled. “And after that, I was like, I’m all in. It needed to stop.”

With a handful of other people who also were dismayed by the vitriol at the meetings, Sorenson started a group to defend the library. At a board meeting, she spoke about MassResistance’s long history of anti-gay activism across the country. She thought it was important that people in Gillette understand that the library’s antagonists weren’t the grassroots group they appeared to be.

Shortly after Sorenson took up her defense of the library, she learned that someone had written to the local school board and demanded to see the lesson plans for a unit she was planning to teach on the Holocaust. A separate message sent to her school’s human resources department accused her of teaching students that Black people should have more rights than white people. Sorenson explained the situation and wasn’t disciplined, but the two complaints took time and effort to resolve. When Sorenson looked into it, she found out that both had come from Arthur Schaper.

Over the course of the next year, four of the five library board members left their positions—two hit their term limits, and two resigned early, maybe because the job had become too stressful. In their places, the elected county commissioners appointed a slate of conservative new members, including Sage Bear. (Her husband, John, is a Wyoming state representative and leader of the state’s Freedom Caucus.) By August 2022, Charlie Anderson was the lone member who didn’t believe that books that referenced sex needed to be moved to the adult section.

The newly remade board moved swiftly. In September, five months after the “Marxist lesbian” tweet from Drabinksi, Bear proposed reconsideration of the library’s affiliation with the ALA. During the public comment session of the next meeting, most speakers supported the Association. A retired children’s librarian recalled that she had attended four of the group’s conferences during her 27-year career “to get tools to put in my toolbox so I was a better storyteller, a better story-time librarian.” A local dad thanked the librarians for the puppet show he had taken his children to every Thursday night for eight years. “If that was a result of ALA,” he said, “by golly we really should keep them around.”

Still, the board voted 4 to 1 to become the first public library system in the nation to cut ties with the ALA. The decision meant that Campbell County librarians would no longer be allowed to attend annual conferences—where librarians build community and share knowledge—or apply for crucial grants from the organization. It also meant that they would not be able to train new employees or fulfill their continuing education requirements through programs affiliated with the group—which almost all library trainings are. The magnitude of the move became apparent almost immediately when the staff discovered that they couldn’t train an entry-level employee to catalog books, because every single cataloging course available was affiliated with the ALA.

The board wasn’t finished. At a March 2023 meeting, Bear proposed a set of revisions to the collection development policy, including a clause that expanded the prohibition of sexually explicit books from the children’s section to the entire library. The revisions, Bear said, had been drafted by Hugh Phillips, an attorney with Liberty Counsel, a Florida-based Christian group dedicated to “advancing religious freedom, the sanctity of human life and the family through strategic litigation.” Its other recent projects have included providing legal guidance for people seeking Covid vaccine exemptions, suing the SPLC over its list of hate groups (on which Liberty Counsel appears), and successfully overturning gay conversion therapy bans in several US cities. Bear claimed she had found Liberty Counsel on her own, but records obtained by the Gillette News-Record revealed that Schaper had suggested she reach out to them.

Over the next few months, the board members, led by Bear, pressed forward on their campaign to protect the youth of Gillette, at least as they saw it. They repeatedly ordered the library’s executive director, Terri Lesley, to relocate books from the children’s section to the adult section, but Lesley refused to move any books that hadn’t gone through the library’s official book complaint protocol, which can take several months. In July, the board gave Lesley an ultimatum: Either comply with its orders or be fired. Lesley chose the latter, but she demanded that they do it at an open meeting. Hundreds of people of people showed up, most of them to support Lesley. Charlie Anderson wore his Fahrenheit 451 T-shirt in honor of the occasion. As Lesley left, newly unemployed, the crowd gave her a standing ovation.

The library board meeting at the Campbell County Public Library on August 28, 2023.

Kiera Butler

These are uneasy times—in Gillette and everywhere else. The pandemic is not yet so far in the rearview mirror that it’s been forgotten, and on the horizon is the turbulence of the 2024 presidential election. During periods of uncertainty and political upheaval, collective anxiety tends to coalesce around children. Think of the civil rights movement, when crusading white parents claimed that desegregation would lead to Black boys raping white girls, or of the “satanic panic” of the 1980s, when, as more women began to work outside the home, day cares were accused of ritualistic child molestation.

There is an economic component to these trends. Melinda Cooper, an Australian sociologist who studies the financial forces that determine the role of families in American society, reminded me that conflicts over the use of taxpayer money often center on the moral lives of children. Teachers have long been the obsession of conservative groups, who see them as immoral usurpers of parental authority. Cooper has written about this dynamic during the ’60s and ’70s, and then again during the tea party movement in the 2010s—and she sees the attack on librarians as the latest chapter. As she put it in an email to me explaining the fears of parents’ rights proponents: “The recurrent theme seems to be local government using the wealth of the private family home to attack the private family, channeling money to teachers, librarians, etc. who want to undermine the authority of parents.”

The morning after Ben Decker had told me that he was worried about societal collapse, we met up at a cheerful Mexican restaurant festooned with garlands of colored paper cut-outs. I asked him to elaborate on his views. Leaving aside for the moment the question of whether the ALA actually had a Marxist agenda—the group says it does not—I asked, “Let’s pretend the ALA accomplishes all of their goals. What do you imagine might happen?”

“It’s tied to a whole lot of other things outside the library situation,” he replied. With no children of his own, Decker works alongside recent high school graduates at a job he didn’t want me to name because his boss doesn’t like him mentioning his workplace in his activism. He told me his young co-workers seemed depressed. He fears that schools are demoralizing children by teaching them about climate change, which he doesn’t believe in, and that children are confused by the idea that gender is a spectrum rather than a binary. Schools’ lessons on gender inclusiveness, he thinks, have made trans identity a status symbol among teenagers. (This theory has been widely discredited.) “Say you’re a weird kid who just doesn’t fit in,” he said. “And then if you say now, I’m gay, or I’m trans or whatever, everyone’s like, you get accepted.” When I suggested that some queer kids still get bullied, he told me he had been bullied because he was short, and that bullying was part of growing up. “Not everybody’s always going to be treating you nice.”

Though Ben was calm and friendly when we spoke, when he started talking about children and the future I detected a certain sense of dread. I saw that same anxiety in Sage Bear, when I met her at the dry-cleaning business she runs with her husband, the Wyoming Freedom Caucus leader. Sitting across from me in the alterations room, Bear, who is middle-aged and has lived in Gillette on and off for her whole life, was guarded and terse, a dramatically toned-down version of the public firebrand. She told me that she had first expressed interest in being on the library board early in 2021, when she had heard in the news—which she mostly gets from YouTube and Tucker Carlson—that libraries were considering getting rid of some Dr. Seuss books because of their racist illustrations. I asked her if this had happened at the Campbell County Public Library. “No,” she said. “I just wanted to get involved if this was coming down the pike.”

Bear worries a lot about Gillette teenagers, some of whom work at her dry-cleaning business. Since the pandemic, she said, she has noticed them retreating more into the worlds of their phones, noting that, unlike the kids of her generation, “the teens who work for me, they don’t even want to drive, because, they’re more interested in being here,” she said, miming a phone in her hand. Once appointed to the board, she became concerned about the presence of sexually explicit materials in the library. “Studies have shown that kids just don’t make good decisions—males, not until they’re 26 or something,” she said. “They are risk takers. And when they start showing them this stuff, they they’re going to take those risks.”

Bear has probably thought more than most about the inner lives of teenagers. I learned from an old newspaper article that she had lost her 18-year-old son, the younger of her two children, to suicide in 2011. I wasn’t planning on bringing it up, but then she did. “You wrestle with, what did I do wrong? I think it just comes down to boys make rash decisions,” she said. “He just got behind in his schoolwork and didn’t want to do it and thought he’d get out of it!” She gave a sudden, very loud, and rueful laugh.

The community showered Bear with kindness in the days and weeks after her son’s death. Yet, she couldn’t stop wondering if deep down her neighbors believed that she had failed as a parent—likely putting a distance between her and the town she’d lived in for decades. “In a weird way it prepared me for the library board,” she said. “A lot of people are judging me, and it’s rolling off my back, and it just doesn’t bother me, because I’m standing up for what I believe in.”

As it turned out, tragic loss is something that Sage Bear and Jenny Sorenson—the 44-year-old English teacher who had organized the group to stand up for the library— have in common. Sorenson, with shoulder-length blond hair, bright blue eyes, and a warm yet direct way of speaking, brought her daughter, a 17-year-old high school senior named Avery, when we met at the library. We sat at an out-of-the-way table behind the fiction section during the library’s weekly visit from a pianist. The soundtrack to our conversation included two versions of Bette Midler’s “The Rose,” Pachelbel’s “Canon,” and Billy Joel’s “Piano Man.”

When Sorensen and her husband moved to Gillette as a young couple 20 years ago, they struggled to make friends and find things to do. So, like the Andersons, “we kind of rolled up our sleeves and got involved.” Serving on various boards and committees, they saw the city transform into the kind of place “that we wanted to have our roots in.” Once her kids were born, Sorenson took advantage of the many resources the town offered for young families—swim lessons, art class, sports, and taking her son and Avery to story time and other library programs. She joined the board of the foundation that fundraises for the library, and her husband was appointed to the library board. He served on it until he died in 2017 at age 38 while leading a climbing expedition at Devils Tower National Monument. The library, she said, “is part of his legacy.”

Avery has attended a few library board meetings, but she stopped going because they were too upsetting. “She’s very well put together about them,” she said, gesturing to her mom. “But like when you’re actually there, it’s just constant bombardment.” Avery, who has long, stick-straight blond hair and glasses, spoke softly but with the self-possession that made me occasionally forget she was a teenager. For Avery, the shocking thing wasn’t so much the existence of homophobia, it was having adults express it. “I mean, I go to public high school in Wyoming—you’re gonna hear teenagers being kind of annoying and weird,” she said. “But I’ve never heard this much hate.” I asked her whether she planned to stick around town after graduation. She sighed heavily. “I’ve always liked Wyoming,” she said. “My family’s been here since pioneer times. This is just where we’ve always been.”

Avery was sad, but it wasn’t because she was being taught about climate change, or trans identity, or even because she was on her phone constantly. She was sad because the town where she grew up, where everyone had always seemed so devoted to her happiness and success, had become a foreign country. What was once familiar felt sinister, and the walls were closing in. It was possible that Avery had developed a case of cabin fever.

In July, Bear and another Campbell County Library Board member, Chuck Butler, joined forces with activists in other states to launch the World Library Association, a conservative alternative to the American Library Association. The group’s website links to Campbell County’s new collection development policy as a model. Its page about librarians is strangely hostile. “Gone are the days of librarians being thought of as mousy older ladies with neat gray buns, half-moon glasses, and a finger constantly placed against the lips to shush loud patrons. These days, it’s considered hip in the profession to be a dark-rimmed glasses-wearing, wildly colored hair-dyed, tattooed punk librarian,” says the website. “What’s coming with this paradigm shift of what a librarian should look like is an aggressive increase in librarians feeling they need to do battle with patrons instead of simply serving them.”

I read that bit to Cooper, the sociologist, and she laughed because this dynamic was so familiar. She shared an excerpt from her forthcoming book Counterrevolution: Extravagance and Austerity in Public Finance. During the social upheaval of the 1960s and ‘70s, she wrote, teachers were portrayed by conservative activists as uppity ballbusters. “If the suburban home was the domain of the blue-collar family man and his wife, the public school was reviled as the fiefdom of the overly powerful white-collar woman, whose wages posed a direct threat to the authority of husbands and fathers.” Now librarians were the women who needed to be put in their place.

Deborah Caldwell-Stone, the director of the ALA’s Office for Intellectual Freedom, told me that her staff has documented escalating harassment of librarians over the last year and a half. But beyond that, she said, she sees the movement as an assault on the very idea of libraries as a public good. “The threat here is to diminish the idea of librarianship—as a professional, nonpartisan service that really is a range of services and access to information—to simply [providing] book warehouses, and then only books that are approved by the vocal minority,” she said.

I asked Bear if the World Library Association offered any training opportunities for librarians. Not yet, she said, but she hoped that it would someday. She’s tired of the library drama, though, and would soon “like to get back to the fiscal issues of what the board typically does.” But that won’t happen at the next meeting—the board has to continue the discussion about what kinds of books should be considered explicit. “It doesn’t have to be, let’s say, bestiality, in order to meet that threshold,” Bear explained. “I want it to meet just a normal, could-your-grandmother-read-this-to-your-kindergartener kind of thing.” Over the summer, library skirmishes have erupted in Iron River, Wisconsin, Wells County, Indiana, and Citrus County, Florida. If Avery Sorenson moved somewhere else, it might be different. Also, it might not.

By the time I finished talking to the Sorensons, it was late in the day. The piano player had finished her set, and the afternoon sun streamed through the picture windows. I took the elevator down to the young adult section, the “dark basement for teens” that had been ominously mentioned at meetings. I found the dungeon in question to be both sprawling and cozy. The main room was brightly lit, with a few different areas where kids could congregate. An adjoining smaller room contained a workbench, tools, and building materials—a makerspace. At a central table, two tweens played chess. A few more lounged in a nook with ottomans and comfy chairs. There was a soda vending machine with magnetic poetry on the side. Posters on the walls advertised weekly activities: chess club, anime club, open-play gaming. Above one of the bookshelves was a mural, clearly created by a kid, that showed a vintage camper van bearing a slogan, in big, red capital letters: ALL TOGETHER NOW. Beside a campfire, two teenagers clutched books, reading under the big, bright blue Wyoming sky.