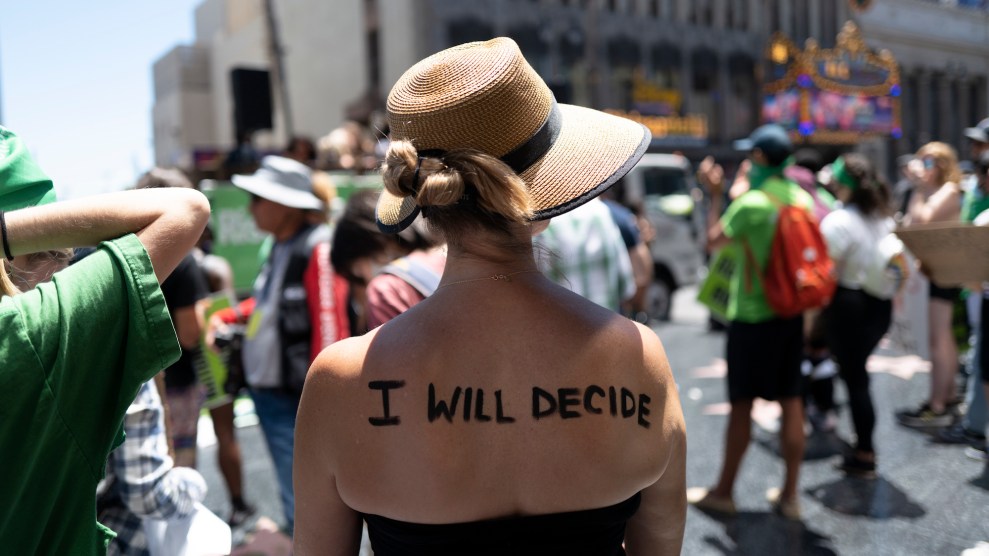

Richard Vogel/AP

Abortion-rights opponents have long said their goal is to end abortion nationwide. So when they succeeded in overturning Roe v. Wade in June 2022, it seemed to be the closest they’d ever come.

Yet new data is making it increasingly clear that in the 12 months after the court ended the national right to abortion, licensed clinicians provided slightly more abortions nationwide, not fewer. According to numbers released Tuesday by the Society of Family Planning, a professional association for healthcare providers who specialize in abortion and contraception, even as 14 states enacted near-total bans on abortion, the number of abortions performed in states bordering the new abortion deserts surged, making up the difference. In particular, California, Florida, Illinois, North Carolina, and New Mexico saw their monthly abortion numbers skyrocket.

The report, the fourth installment in the Society of Family Planning’s #WeCount project, tallies a year’s worth of medication and other abortions reported by licensed providers working in brick-and-mortar abortion clinics, private medical offices, telehealth clinics, and hospitals. The researchers did not attempt to count self-managed abortions. Their findings are in line with research released last month by the Guttmacher Institute, which used a statistical model, historical data, and surveys to estimate that 46,000 more abortions took place in the first six months of 2023 compared to the first six months of 2020. “We’re using two different methodologies and finding more or less the same patterns,” says Rachel Jones, principal research scientist at Guttmacher.

The new data underscores the argument from abortion-rights advocates that abortion bans don’t stop abortions. But the overall slight rise in abortion numbers nationwide “is not evidence that the bans are not working,” warns Ushma Upadhyay, #WeCount co-chair and a professor at the University of California, San Francisco. “What actually happened during these 12 months is that abortion access plummeted to zero in some states, while increasing to meet the acute need in others.”

Meeting that need has required a monumental effort across the abortion care infrastructure. Providers relocated or opened new clinics while advocates switched into overdrive, operating networks of organizations that provide funding, support, and information to scared and confused patients. Since Dobbs, at least 114 facilities have raised limits on how late in pregnancy they will perform abortions, expanding options for patients seeking an abortion after the first trimester, according to recent UCSF research. State and municipal governments set aside nearly $208 million to pay for abortion, contraception, and support service—including a $20 million budget line item in California paying for out-of-state patients to travel there for abortions. Donations to abortion funds soared, too—at least temporarily. Meanwhile, virtual clinics that provide abortion pills by mail have grown steadily since 2020, when a federal court (later followed by the FDA) halted an old rule requiring patients to pick up the medication from a clinic in person. Since Dobbs, the average monthly number of abortions provided by virtual-only clinics increased by 72 percent, according to the data released Tuesday.

All of these changes add up to expanded access in states that protect abortion—benefitting both in- and out-of-state patients. Yet this new normal is fragile. The Supreme Court is currently considering whether to take up a case that could eliminate access to the common abortion medication mifepristone. The state supreme court in Florida, another surge state, is currently considering whether to affirm a 15-week ban on abortion; if it does, a 6-week ban will take effect shortly afterward. Amber Gavin, vice president of advocacy and operations at A Woman’s Choice, an independent clinic with locations in North Carolina and Florida, is awaiting that decision nervously. “I’m truly not sure where the thousands of people across the Southeast who need abortion care after six weeks will turn to, as many of our abortion clinics are at capacity and it could take weeks for folks to get an appointment,” Gavin says.

As always, the curse is time: Every week it takes make a decision, find an appointment, and pull together the money—then arrange time off work, childcare, and travel—pushes a patient further into pregnancy. Take too long, and you could pass gestational limits in surrounding states, or require a more expensive and time-consuming procedure. Megan Jeyifo, the executive director of the Chicago Abortion Fund, says she hears stories about “the difficulty of parsing through disinformation and fake abortion clinics, confusion regarding legality, worry about costs and travel barriers, lack of available appointments in surge states, and delays due to securing time off from work or childcare.” Before Dobbs, the average caller to the Chicago Abortion Fund’s hotline was 9.9 weeks into pregnancy; after, that figure rose to 15.6 weeks.

Could Dobbs not only have led to overall increases in abortion, but also caused more people to get abortions later in pregnancy? “It’s exactly the question that everyone is asking,” Upadhyay says. “It’s important to know all of the effects of these bans.”