A shale gas well in St. Mary's, Pennsylvania.Keith Srakocic/AP

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Katie Muth knew it would be a long shot. This January, the Pennsylvania state senator reintroduced three pieces of legislation aimed at closing loopholes in the laws governing how the oil and gas industry disposes of its solid and liquid waste.

In Pennsylvania’s Republican-controlled Senate, Muth said any legislation hampering business as usual for oil and gas companies would garner little to no bipartisan support. Still, there is utility in getting “a lot of legislators on the record voting down clean water,” she said.

Together, SB26 and SB28, which have been referred to the chamber’s Environmental Resources and Energy Committee, would add language to Pennsylvania’s Solid Waste Management Act that would classify oil and gas waste as hazardous, and compel companies to more thoroughly test that waste prior to its disposal.

This waste is comprised of solids, called tailings, and liquids, known as “produced water,” or brine, which contains proprietary chemical additives, hydrocarbons, heavy metals and salt concentrations sometimes seven times higher than sea water, and can be radioactive. “The exemptions don’t remove the harm” that waste from the oil and gas industry inflicts on Pennsylvanians, Muth said. “It just saves corporations money where Pennsylvanians have to suffer.”

Residents in Pennsylvania and across the country have expressed concerns about oil and gas waste disposal landfills, holding ponds and storage wells being located in their communities, and researchers and journalists have uncovered instances in which drinking water and freshwater species have been poisoned by produced water—which bubbles back to the surface of a fracked well.

Senate Bill 29, also with the Environmental Resources and Energy Committee, would go beyond closing loopholes by introducing regulations that require landfills to test the toxicity of residual oil and gas waste and any runoff, or leachate, it creates. Once dumped in landfills, oil and gas waste can mix with rainwater to generate highly toxic leachate that can contaminate the surrounding environment as runoff or run through storm sewers to wastewater treatment plants, where it is disposed of in local waterways. SB29 would also prevent landfills from accepting any waste that is radioactive.

“These are loopholes that allow one specific industry to do business in a dirty, horrible way,” said Muth, speaking over the phone ahead of the new legislative assembly in Pennsylvania, which began Aug. 30.

A representative from Marcellus Shale Coalition, which represents drillers in Pennsylvania, pushed back on the characterization of the industry’s waste-disposal standards as benefiting from a loophole.

“Pennsylvania and the federal government have strict regulations regarding the handling, treatment and disposal of waste that are based on the characteristics, not the industry that generates it,” the coalition’s President, David Callahan, said in a statement. “While we abide by the same regulations as all waste generators, the oil and gas industry has some of the most robust tracking and disposal standards of any Pennsylvania industry, as all waste generated must be sampled, analyzed and approved by environmental regulators, and every individual waste truck undergoes screening prior to landfill disposal.

“Our members are committed to safe, responsible operations and continue to drive waste and water management innovations, including developing water recycling practices more than a decade ago that have become standard procedure today.”

For Gillian Graber, executive director and founder of Protect PT, an organization focused on educating Pennsylvanians living in the state’s southwestern counties on the impacts of fossil fuel drilling, this kind of legislation is desperately needed. “Produced water is super problematic,” Graber said, because it is highly toxic and difficult to dispose of safely.

During the first week or two after a well is fracked for natural gas in Pennsylvania’s Marcellus shale, water known as flowback is allowed to drain from the well slowly so that sand, used as a “proppant” to hold the rock apart while the methane escapes, doesn’t come up with it. Gas can’t escape while water fills the well.

This flowback contains the initial chemical additives, or fracking fluids, plus chemicals and minerals it absorbed while coursing through the Marcellus. As the well starts producing gas, the water that comes from deep underground is called produced water. Because it has had more time to dissolve elements of the shale and percolate in the Marcellus, it contains a higher concentration of chemicals, along with numerous hazardous compounds, which can include bromide, arsenic, strontium, mercury, barium, radioactive isotopes such as radium 226 and 228, and organic compounds, particularly benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene and xylenes.

Only about 5 to 10 percent of the millions of gallons of water used to frack a well initially comes back to the surface. The Marcellus is a dry formation that absorbs much of the fracking fluid.

The produced water and gas are collected and separated at the drill pad. Liquid is usually stored in onsite tanks until it’s reused or trucked somewhere else.

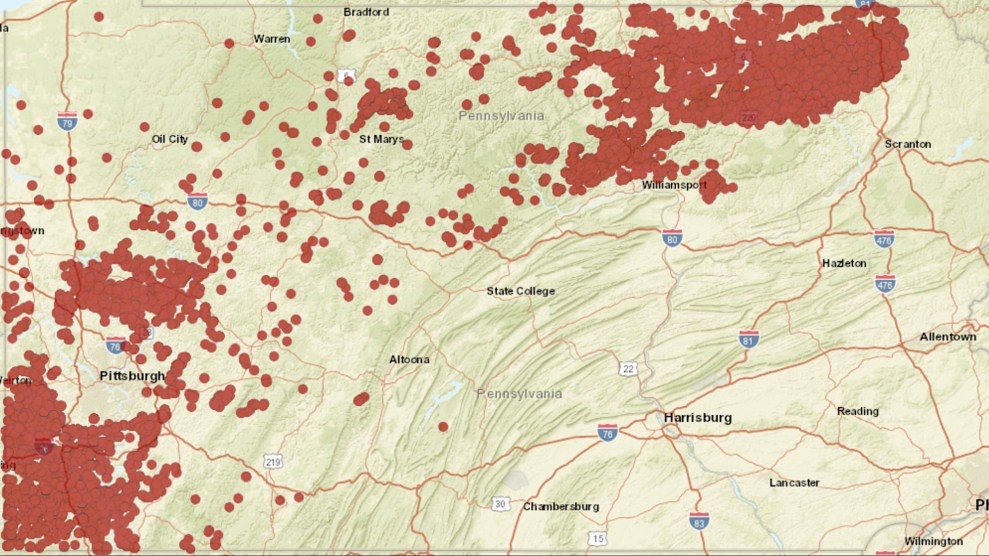

Just trucking produced water across the state from fracking wells to underground “injection” wells for storage, which are located in Pennsylvania and Ohio, can pose serious hazards, even to Pennsylvanians who don’t live near fracking wells, Graber continued. According to data oil and gas companies reported to Pennsylvania’s Department of Environmental Protection the fracking industry generated about 2.6 billion gallons of liquid waste from oil and gas projects in 2022, roughly 44 percent of which was reused for more fracking.

Of the remaining 1.5 billion gallons, only 6 percent was impounded on site and held in large tanks. The overwhelming majority was transferred to an injection well to be pumped deep below ground.

Because natural gas drillers aren’t required by state or federal law to publicly disclose what chemicals they’re using in the fracking process, Graber said that “it is incredibly difficult to know what is being transported on our roads.” The trucks are not required to be labeled as hazardous—an oversight Muth’s bills would correct—even though the produced water they’re carrying often contains radium 226 and 228 and, as a result, truck drivers may not realize they’re hauling “potentially radioactive” materials, said Graber.

Most people, she added, “don’t have any notion of just how bad this problem is.”

Six other Senate Democrats initially joined Muth in co-sponsoring these bills, and Graber said that “it would be great if other people would be as forward thinking as Senator Muth.”

Graber is dismayed that this issue is politicized, but hopes that the polarization is beginning to wane. In July, Rep. Charity Grimm Krupa, a House Republican, announced her intent to introduce legislation that would ban the state from issuing permits for injection wells within Pennsylvania.

But until there’s a robust bipartisan groundswell for legislation that sheds more light on the composition and effects of produced water, Graber said she expects to remain frustrated by an apparent double standard: local governments welcome new fracking wells, but draw the line at disposing the waste that comes from them.

“What I think that they’re neglecting to realize is that the only reason why they’re being targeted as a waste dump is because the waste exists in the first place,” she said. “How can you say you support an industry but not the thing it makes?”

Others who monitor fracking waste in Pennsylvania believe that testing, documenting and regulating what exactly is in produced water is necessary to help hold accountable an industry that’s become far too comfortable maneuvering through legislative loopholes.

Matt Kelso, the manager of data and technology at FracTracker Alliance who supplied Inside Climate News with data about the amount of toxic wastewater in the state, views produced water as “fundamentally risky,” and a problem that the oil and gas industry is not close to solving. “The water is hard to deal with,” he said. “If you dilute it, then you have more of it. And if you concentrate it there, then you have a higher level of contaminants” on site, he said.

“If they treated it honestly” and were forced to handle waste in the same manner as other regulated entities, he said, “I think it would be really [bad] for the industry.”

Asked what impact her bills would have on the oil gas industry in Pennsylvania, Muth agreed with Kelso’s assessment. “It would cost them more money,” said Muth. “That’s why they don’t want to do it.”

If these bills don’t make it to the floor for a vote, Muth is prepared to keep adding amendments to future legislation, in large part to get people on the record. “It shows people that their legislators are voting down the opportunity to protect their constituents from this waste cycle,” she said.