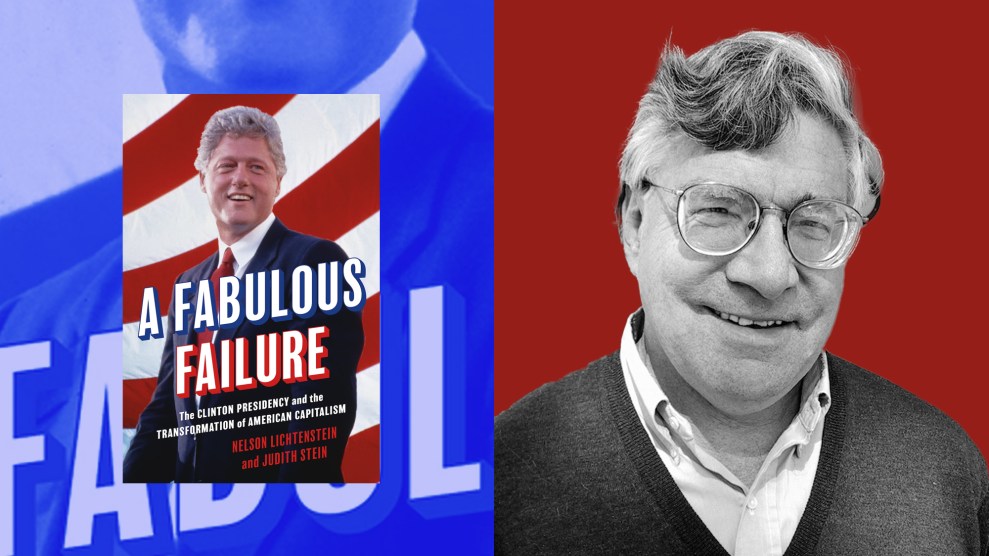

This piece is adapted from A Fabulous Failure: The Clinton Presidency and the Transformation of American Capitalism by Nelson Lichtenstein and Judith Stein. The book will be available from Princeton University Press on September 12. This excerpt is accompanied by an interview with one of the book’s authors.

On December 14 and 15, 1992, the transition team for the newly elected President Bill Clinton assembled more than three hundred of the nation’s leading economists, executives, politicians, and policy entrepreneurs in Little Rock for an “economic summit.” Almost all agreed with strategist James Carville’s now-famous catchphrase, “The Economy, Stupid,” first posted on a wall of the Clinton campaign’s “war room.” It was time for the government to offer a forceful set of initiatives to increase the productivity of capital and labor, transform key industry sectors, and enhance the quality of American life. “We must revitalize and rebuild our economy,” said the president-elect.

During the summit, Bill Clinton was an engaged and expert ringmaster. For nearly ten hours each day, he sat in a swivel chair at the head of a large oval arrangement of tables: taking notes, asking questions, offering his views. As the New York Times observed, Clinton was “teacher, student, preacher.” Even Republicans were impressed. “After four years of watching the Bush team amateurs,” said Martin Anderson, one of President Reagan’s domestic policy advisers, “it’s fun to watch the pros play again.”

Although no one compared the 1992 Clinton victory to FDR’s election sixty years before, there seemed to be an ideological and generational coherence to the Clinton cadre that evoked a fresh set of hopes. Democrats once again controlled the White House and the Congress after nearly two decades of frustration, defeat, and economic dislocation under every president since Richard Nixon. Robert Kuttner of The American Prospect (who would soon become disenchanted with the Clinton White House) told the same assemblage: “Words fail me in describing what an extraordinary event this is…. This is a magical moment.”

The reforms explored at the Little Rock economic summit were tangible and within an ambitious grasp. It did not seem impossible for Clinton and his allies to make health insurance nearly universal, to stimulate not just economic growth in general but specific industries and occupations that were socially and ecologically important, to manage trade so as to preserve factories and jobs, to enact a welfare reform that did not repudiate a New Deal entitlement, and even to regulate Wall Street finance. Structural reforms of this sort promised to break with Reaganite laissez-faire and renew the allegiance of blue-collar voters to the party of Roosevelt, Truman, Kennedy, and Johnson.

Today, however, Clinton’s presidency wins little respect.

Few liberals want to return the Democratic Party to that era because so many see his presidency as a betrayal of the progressivism that was once the hallmark of the New Deal and the Great Society. Bill Clinton was the first Democratic president since FDR to win two consecutive terms, but that accomplishment seems merely a product of his accommodation to an ideology that privileged trade liberalization, financial deregulation, and privatization of government services, while tolerating the growth of class inequalities. Clinton’s 1996 declaration that “the era of big government is over” seemingly ratified Reaganite conservatism and in the process transformed Republican politics and policy into a hegemonic ethos that liberated global finance and eviscerated Keynesian liberalism.

Although hardly in use during the 1990s, “neoliberalism” became shorthand in the next decade for the fallout: the liberalization of trade, the deregulation of finance, the privatization of government services, the reductions of taxes on the rich, and the evisceration of the labor movement and the welfare state. That the Clinton administration embarked on this path is without doubt. His presidency not only saw passage of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1993 but also the end of a New Deal entitlement in the welfare reform of 1996 and protests against the World Trade Organization (WTO)—and in particular against US support for China’s entry to that organization—in the 1999 Battle of Seattle, which put environmentalists and union labor on the same side of the barricade.

But the neoliberal project was never a seamless unfolding of an all-encompassing ideology, springing full blown from the mind of a Friedrich Hayek or Milton Friedman. Nor was it a Wall Street scheme foisted upon the nation through blunt financial power.

Within the country, the Congress, the administration, and the mind of Bill Clinton himself, much was left unsettled between the time the Arkansas governor burst upon the national political scene. Ideas and proposals were subject to intense debate, first among the ever-growing “Friends of Bill” and then within the White House, among Democratic officeholders, and in academe, think tanks, foundations, journals, and the Democratic Party in all its manifestations.

“The lingua franca of this network was the language of policy, the specifics of governmental activism,” wrote the journalist and White House aide Sidney Blumenthal, who first met the Arkansas governor at one of the “Renaissance Weekend” talkfests that Bill and Hillary attended almost every New Year’s Eve in the 1980s. Blumenthal saw Clinton approaching new ideas and proposals like they were “jazz riffs,” which he played “until he felt he had improvised the right composition. And then he would start again.”

If Clinton and like-minded Friends of Bill were hardly neoliberals when they first occupied the White House, they had moved far in that direction by the time they departed. But this shift in policy and rhetoric was not merely a product of defeat at the hands of corporate enemies and political foes. It was also bred by the set of seductive illusions.

The Clinton administration’s assumption that a new world of technology and markets would lay the basis for both an era of prosperity and progressive statecraft proved sorely mistaken. Instead, the financialized capitalism that Bill Clinton came to champion generated inequality and crisis, opening the door to retrograde forces they had barely imagined. The path toward the management of a capitalist polity would prove far more difficult than Clinton’s partisans could imagine.

Governor Bill Clinton shaking hands with President Reagan in the Rose Garden in October of 1988.

Wikimedia

Bill Clinton came of age in the segregationist South. His values were animated by the revolution in race relations that came out of the 1960s, by opposition to the Vietnam War, and by sojourns at the nation’s elite universities. He was not a “movement” New Leftist, but rather a Southern progressive who had the good fortune to win office and influence during the unique political moment that followed the liberating impact of the civil rights movement, when Democrats in the South could rely upon a biracial electorate to sustain their ambitions. Blumenthal labeled him “the leading meritocrat of America’s first mass generation of college-educated meritocrats.”

In 1973, Clinton returned home to Arkansas, when his state was then among the poorest in the nation, with a per capita income only 43 percent of the rest of the United States. Arkansas had been “Dogpatch” since the nineteenth century, when Mark Twain, in Huckleberry Finn, wrote of its residents as “Arkansaw lunkheads.” But it was a fortuitous time for him to come back and run for office.

The segregationist Democrats who had once dominated politics were clearly in retreat, African Americans were voting in record numbers, and a more moderate Democratic Party still held the residual loyalty of millions of lower-income white voters. To a degree this allegiance was based on their support of the New Deal economic liberalism, which had materially improved living standards throughout the South. Working-class white voters would eventually migrate to the GOP. But not in the 1970s. The culture wars over sexuality, immigration, religion, and abortion had not yet been fully engaged; meanwhile, class politics still retained an animating power, especially during the sharp recession of 1973 and 1974.

In 1974, Clinton ran a terrific but unsuccessful campaign for Congress, Just twenty-eight years old at the time, he gave a rousing spousing to the state Democratic convention. Clinton denounced targets of a classic populist sort: Mobil Oil, New York banks, and the Arab kingdoms that had inaugurated the oil boycott. “The people want a hand up—not a handout,” he said. Among those who thrilled to his campaign were the state’s trade unionists, who whooped and applauded a speech Clinton delivered at the 1974 convention of the Arkansas AFL-CIO in Hot Springs. “Our people just fell in love with the guy,” recalled the AFL-CIO’s Becker in an interview several years later. Clinton raised at least 10 percent of his campaign funds from labor, whose contributions included volunteer door knocking by unionized steelworkers and teachers.

In 1976, Clinton ran for attorney general and won the post with a healthy majority in the general election. But as attorney general, he spurned the unions by refusing to sign a petition to place an amendment on the ballot repealing the state’s right-to-work law. Such statutes, common in the South and Mountain West, weakened organized labor by prohibiting unions from negotiating contracts that made union membership a condition of employment. Advised by Dick Morris, Clinton wrote a series of attack ads warning that unions were “disastrous for the economy of Arkansas.”

Clinton’s disdain for the labor movement primarily reflected a political calculus about who held power and who did not in his state. There wasn’t much industry in Arkansas, so the labor movement was relatively small. More important, the economic powerhouses emerging in northwest Arkansas—Wal-Mart, Tyson Foods, Hunt Transport—were militantly hostile to organized labor. But Clinton and many in his generation were also deeply ambivalent about the labor metaphysic itself, and certainly about the institutions that embodied the “industrial pluralism” that had once seemed so essential to American prosperity and democracy.

In his state a species of low-wage Fordism was still the preferred strategy of firms like Tyson Foods, Wal-Mart Stores, and the Stephens Investment Bank. None of these companies tried to emulate the actual mass-production regime that had powered American industrial growth a half-century before. Not only did these firms employ a non-union workforce at rock-bottom wages, but they fissured their supply chains so as to off-load risk and expense to a set of ostensibly independent suppliers.

Thus, Tyson did employ tens of thousands of workers—many of them African-American and Latino—in a set of poultry processing plants and slaughterhouses whose work regime emulated the most hierarchical and brutal version of a 1920s-era Detroit assembly line. But Tyson also outsourced the production of millions of chickens and hogs to Ozark farmers whose hatcheries and feedlots were subject to the most exacting regulation and control. These farmers were little more than “sharecroppers” standing at the base of a late-twentieth-century supply chain. The same was true of Wal-Mart: store “associates” were direct employees of the fast-growing firm, but hundreds of supply-chain “vendors” were kept on an exceedingly tight leash that was at once financially precarious and entrepreneurially constraining.

After he won the governorship in 1978, Clinton wanted to be the chief executive who began to pull his state out of the social cellar.

But there were definite limits to what a reformer could do in a state that was still dominated by such a close-knit elite. During his first term, Clinton promised Don Tyson that he would raise the weight limit on big trucks to eighty thousand pounds, a real boon for the company. That would put a burden on Arkansas roads. Clinton wanted to raise vehicle taxes to pay for a more robust transportation infrastructure. The proposed taxes were proportional to the weight of the vehicle, so Tyson Foods, Wal-Mart, and other trucking-dependent companies would take a hit—a fair and progressive hit, thought Clinton, since these same firms would benefit directly from the higher weight limits. But they balked, mobilizing their minions in the state legislature against the weight-linked taxes. Clinton then shifted the weight of the new taxes to car owners. It was a characteristic maneuver: when confronting entrenched power Clinton would seek a way around, a compromise so as to take half a loaf rather than none at all.

But such triangulation could backfire, and it did so with disastrous consequences when Clinton ran for reelection in 1980. All those vehicle taxes now fell on the good old boys who drove their pickup trucks and heavy clunkers around rural Arkansas. They hated the cumbersome procedure that required them to get their vehicle inspected, prove they had paid last year’s car tax, and then pay the higher car registration fees.

Clinton lost his 1980 reelection bid to a conservative Republican. It was a humiliating defeat. He recaptured the governorship in 1982 after apologizing to the Arkansas electorate for past “errors.” He was reelected in 1984, 1986 (now a four-year term), and 1990.

Bill Clinton’s sojourn in Arkansas politics demonstrated the degree to which he wanted to be a progressive governor. Clinton pushed for raising educational standards and advancing the state’s economic development and the living standards of its citizens. But market forces alone would not transform the state.

Clinton faced enormous obstacles, largely emanating from a self-confident business class who combined the most advanced technological and organizational innovations with a low-wage, outsourcing employment strategy that would prove a social and economic dead end for the vast majority of Arkansans. He understood this conundrum, but his disdain for organized labor left him without the most potent tool he could have wielded to counter that power. Instead, Clinton kept up a restless quest for any innovation, originating at home or abroad, that might enhance development without even the semblance of a conflict with the corporate behemoths of his state.

Clinton’s frustrating efforts to transform the Arkansas economy were but a microcosm of the problems that confronted American liberals in the 1970s and 1980s, as he went from beloved governor to potential president. The new normal seemed to be recession, inflation, and deindustrialization, maladies that failed to respond to the tool kit of New Deal–era remedies that for a third of a century had propelled US economic growth, doubled the standard of living, and sustained Democratic Party hegemony. Beginning with the sharp recession that followed the 1973 oil crisis, the United States seemed to have entered an era of limits, both economic and political.

The road to a Reaganite ascendency was now open, and many liberals in academe and politics were also coming to see the virtue of the market as a mechanism that rewarded efficiency, spurred economic growth, and even enhanced democratic practice. But another ideological current was also present in the policy circles inhabited by Bill Clinton and his increasingly wide network of friends and collaborators. “Industrial policy,” an effort to manage key enterprises and economic sectors, especially in terms of trade and competition with other industrial nations, was perhaps the most serious and politically realistic alternative to Reaganite conservatism during the 1980s and early 1990s.

A reconfiguration of liberalism emerged from this new political and economic terrain. Initially called “neo-liberals” and “Atari Democrats” in the early 1980s, these erstwhile liberals sought to salvage progressive values in a global economy where the old paths to a good society seemed utterly blocked. The labor movement was in decline, tax revenues were growing paltry, and high-wage manufacturing was giving way to lower-paid employment in a vast retail, fast-food, and hospitality sector. Many thought that the New York City fiscal crisis signaled the end of an era when the most liberal constituencies could expand the welfare state; likewise, the tax revolts of the late 1970s in California, Massachusetts, and elsewhere proscribed any new round of social spending. Bill Clinton had failed to win reelection in 1980 largely because he hiked automobile registration fees to pay for new roads and highways, a fiscal lesson he would not forget.

The idea that capitalist markets are essential to, or even define, the democratic idea has always been present in the West, but this sentiment achieved far greater power after 1989 and the tearing down of the Berlin Wall. In a maddening piece of ideological larceny, market triumphalists invoked the ultimate sanction, once the principal asset of the left: the stamp of historic inevitability. Words like “reform” and “liberalization” came to denote the process whereby an open market in labor and capital now replaced the regulatory regimes, either social democratic or autocratic, that had been erected earlier in the century.

Neither progressive intellectuals nor many in the Democratic Party bought into this sort of triumphalism. Communism might have fallen, but American capitalism often seemed less the winner than the survivor of the Cold War. Indeed, it was Paul Tsongas, a Massachusetts Democrat often identified with market solutions to US economic problems, who famously declared during his campaign for the 1992 presidential nomination that “The Cold War Is Over: Germany and Japan Won.”

In a similar vein Bill Clinton began his run for president, he used the Little Rock inauguration of his campaign to announce that “our competition for the future is Germany and the rest of Europe, Japan and the rest of Asia.” Those rivals had “productivity growth rates that were three and four times ours because they educate their people better, they invest more in their future, and they organize their economies for global competition while we don’t.”Wrote Denis MacShane, a Labour Party MP, “For years socialists used to argue among themselves about what kind of socialism they wanted. But today, the choice of the left is no longer what kind of socialism it wants, but what kind of capitalism it can support.”

In this era, Bill Clinton campaigned for the presidency as a progressive. Like the New Democrats, Clinton said he wanted his presidency to focus on economic growth, not income redistribution, but that idea was hardly at variance with the industrial policy advocates. A warmed-over Keynesianism was not enough. In a global economy, growth would require the kind of governmental investment programs, regulatory reforms, trade negotiations, health provision, and progressive changes in the tax law that were essential if a form of managed capitalism was to be put on the agenda.

Campaign aide James Carville achieved a certain political immortality by coining the slogan “The Economy, Stupid!” It was posted on the wall of the Clinton campaign’s Little Rock war room early in the fall of 1992 to keep campaign strategists intently focused on the economic welfare of working America. But it was also a cautionary injunction: stay away from the social controversies and cultural flashpoints that an increasingly desperate George Bush was seeking to highlight. Of course, most Clinton Democrats were social liberals who favored affirmative action, a process for allowing gays to serve in the military, and various energy conservation measures, which by the early 1990s were as much cultural markers as economic programs.

Historians and journalists would later highlight his identification with the resolutely centrist Democratic Leadership Council, but Clinton was not its creature. He readily used the DLC political network and often adopted its rhetoric, but when it came to his campaign and to many of his presidential appointments, Clinton deployed the arguments and outlook prevalent among those who sought a vigorous management of the economy. The sharp recession that enveloped the nation in the early 1990s provided a near-perfect context in which his campaign could showcase an economic liberalism that was more robust and innovative than that of any other Democratic presidential candidate since 1964. That posture would not last, but it got him elected president of the United States.

Pres. Bill Clinton meeting with Capitol Hill leadership and House Speaker Newt Gingrich at the White House.

Diana Walker/Getty

Bill Clinton often called his presidency a “bridge to the twenty-first century.” But that arch would prove fragile and misaligned, with foundation pilons and suspension cables that could not bear the weight of the inevitable storms, political and economic, that swept the nation in the years after he left office. The Clintonites got both the economics and the politics wrong.

Chief among the frustrations for many on the left was Clinton’s eventual support of the North American Free Trade Agreement. Bill Clinton’s decision to push NAFTA through Congress in the fall of 1993 was the product of a set of illusions: a wishful search for a moment of bipartisan consensus after the divisive budget battle; the promise of balanced growth and job creation between two economies starkly different in their structure, incomes, and wages; and a belief that in such circumstances free trade would not exacerbate the variegated set of class antagonisms and racial resentments that were generated by mass immigration, capital mobility, and an employer offensive against American labor that was gaining power and legitimacy even in the fabulous 1990s. The idea that a “new economy” had transformed American politics proved a powerful myth.

Thus, by the end of the Clinton presidency this “new economy” construct had become a pervasive and powerful vision, offering a techno-social solution to virtually every problem confronting the nation. The idea that a globalized economy combining high technology and entrepreneurial innovation had generated a new sort of capitalism proved intoxicating, from the Apple headquarters in Cupertino to the corner office, the campus quad, and Capitol Hill. The concept became an all-purpose rationale for almost any sort of political or social program. For Robert Reich, the new economy promised to transform labor relations and worker skills; for Alan Greenspan, it would keep interest rates low because new economy productivity levels would mean that wage increases and full production were no longer inflationary; for Gene Sperling, Charlene Barshefsky, and New York Times columnist Tom Friedman, rapid communications and efficient transport networks linked together a new era of free trade and democratic reform. For Larry Summers, Al Gore, and President Clinton, a technologically sophisticated new economy provided the “modernizing” rationale for the deregulation of telecom, banking, and international finance. Evoking the racially progressive dreams engendered during his Arkansas youth, Bill Clinton told the White House conference, “I believe the computer and the internet give us a chance to move more people out of poverty more quickly than at any time in all of human history.”

Of course, America was generating a new economy, but it was far different from what Silicon Valley and its White House cheerleaders had imagined. Wal-Mart and McDonald’s, Amazon and FedEx, Marriott and HCA Healthcare, all were giant growth companies. Software engineers and computer support specialists were among the fastest-growing occupations, but when it came to sheer numbers, occupational growth was still concentrated in low-wage, low-skill jobs in retail trade, food preparation and restaurants, hospitals, nursing homes and home health care, janitorial services, and offices. These jobs were often structured and supervised by a new digital infrastructure—call center and warehouse work were prime examples—but they were hardly of the sort envisioned by “new economy” enthusiasts. Indeed, that phrase faded in the new millennium, replaced by descriptors of a far darker character: “the gig economy,” “surveillance capitalism,” and “the fissured workplace.” Of course, none of this lessened the impact of high-technology companies on American politics and discourse. Silicon Valley’s determination to “change the world” had been backstopped by a tenfold increase in the amount of money Democrats raised from that sector between the 1994 and 2000 election cycles.

If the new economy was not panning out, neither were the baroque financial innovations and deregulatory banking rules that Clinton’s economic team had promulgated. Once the scale of the 2008 meltdown became apparent, virtually all of the key Clinton administration figures—Rubin, Greenspan, Levitt, Sperling, and Clinton—admitted that their faith in deregulated financial markets had been misplaced. For a moment it seemed as if the absolute collapse of the most important banks, brokerages, and insurance companies was leading to either the breakup or de facto nationalization of much of the US financial infrastructure.

When Clinton and Gore opened their Little Rock summit in December 1992, a sense of crisis pervaded the discussion of how the American version of world capitalism might be transformed. Seven and a half years later, in April 2000, Clinton convened a “White House Conference on the New Economy.” A techno-triumphalism pervaded the conclave, with Clinton announcing, “We meet in the midst of the longest economic expansion of our history and an economic transformation as profound as that that led us into the industrial revolution.” At Little Rock the leadoff speaker had been Robert Solow, the Keynesian theorist of economic growth; at the 2000 White House conference it was Abby Joseph Cohen, a famed and hyper-bullish stock market analyst from Goldman Sachs.