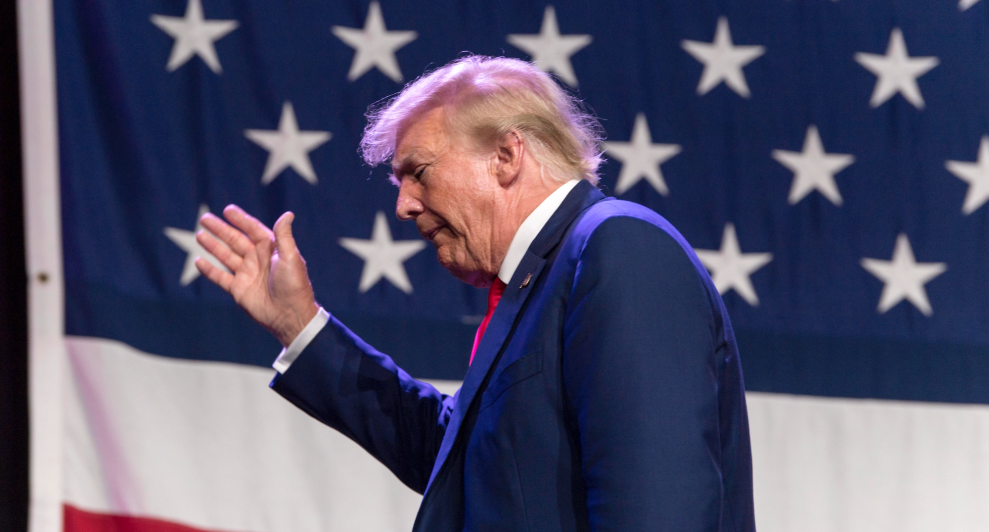

Megan Jelinger/AFP/Getty

Former President Donald Trump was indicted in Georgia late on Monday on charges related to his desperate attempts to overturn the 2020 election. The charges, brought by Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis, follow an investigation that lasted some two and a half years.

The indictment charges Trump with 13 felonies, many centered on allegations that he conspired to violate state laws forbidding the creation and filing of false documents, statements, and writings as part of the plot to send a fake alternate slate of Republican electors. Other charges include soliciting public officials to violate their oath, in relation to Trump’s pressure campaign targeting state officials to help him overturn Georgia’s 2020 results.

The indictment includes alleged violations of Georgia’s powerful RICO law, typically used to prosecute gangs or other criminal organizations. Prosecutors can seek 20-year prison sentences under that anti-racketeering statute.

Charges were also handed down against 18 other people, including several close associates and allies of the former president—among them Rudy Giuliani, attorney Sidney Powell, former White House chief of staff Mark Meadows, Trump campaign lawyer Jenna Ellis, Republican operative Mike Roman, and Jeffrey Clark, a former Justice Department official.

Trump’s post-election meddling in Georgia was a major prong of his months-long campaign to reverse Joe Biden’s victory—an unprecedented effort that began even before voting took place, and that continued even after the violent attack on Congress on January 6, 2021. The Georgia indictment comes two weeks after federal charges were filed against Trump in connection with these efforts.

But even within that broader context, Trump’s attempts to intervene in the Georgia vote count seemed especially egregious—and well documented. During a phone call on January 2, 2021—four days before his supporters stormed the US Capitol in an unsuccessful attempt to stop certification of the election—Trump requested that Georgia Secretary of State Brad Raffensperger “find” the votes to overturn his loss in the state. The Washington Post published a recording of the call the next day.

“I just want to find 11,780 votes,” Trump said on the call—clearly aware of the fact that Joe Biden had won Georgia by just 11,779 votes. Trump repeatedly, and falsely, insisted that the state had been fraudulently stolen from him. During their conversation, he went so far as to threaten Raffensperger with criminal prosecution.

Willis, the Fulton County DA, opened her investigation in February 2021, about a month after the call was made public. A special grand jury she impanelled to investigate the matter began hearing testimony in June of last year and wrapped up its probe in January—two years after the release of the recording. By then, her investigation had expanded to cover other portions of the plot to overturn the election, including the creation of an alternate slate of electors intended to help deliver the state to Trump. Those grand jurors heard from 75 witnesses, including high-profile Trump allies such as Meadows, Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), and former national security adviser Michael Flynn.

In February, a judge released five pages of the special grand jury’s report, revealing that it had determined there was no widespread fraud in Georgia’s 2020 election. But this teaser did not give any hint about what charges Trump or his allies might face. Some clues came out days later, when the special grand jury forewoman told media outlets they had recommended indictments against multiple people—though she wouldn’t say who. Other members of the special grand jury divulged to the the Atlanta Journal-Constitution that there had been multiple calls, beyond the one the Post published, when Trump pressured Georgia officials to overturn results.

In Georgia, a special grand jury can recommend indictments, but it can’t issue them. In May, court documents revealed that at least eight of the 16 electors the Trump campaign had arranged to cast fake Electoral College votes had been given immunity in exchange for their testimony. In order to secure indictments, Willis empaneled a regular grand jury in July.

Trump and his allies have repeatedly sought to shut down Willis’ investigation. In March, Trump’s lawyers asked the Georgia judge overseeing the investigation to throw out the special grand jury’s report and take Willis off the case. Meanwhile, Republicans in the state legislature pushed through a bill creating a special panel that can censure and even remove elected district attorneys such as Willis for vague reasons—legislation many believe is an attempt to interfere in Willis’ investigation into Trump. In July, with an indictment possibly days or weeks away, Trump’s attorney’s made a last-ditch effort to remove Willis by asking the Georgia Supreme Court to intervene. That court, which is made up almost entirely of Republican appointees, refused.

Trump has personally attacked Willis. Last week, he spread a rumor she had affair with a gang member she was prosecuting, an unsupported smear that Willis has called “derogatory and false.” He has also derided her as a “Radical Left Democrat ‘Prosecutor'” on Truth Social, his social media platform. After Willis argued the legislation empowering a board to remove local prosecutors was racist, Trump accused Willis, who is Black, of being the real racist.

After Trump’s most recent claims, Willis wrote a letter to her staff urging them not to respond to the attack. “We have no personal feelings against those we investigate or prosecute,” she wrote. “We have a job to do. In this office, we prosecute based on the facts and the law.”