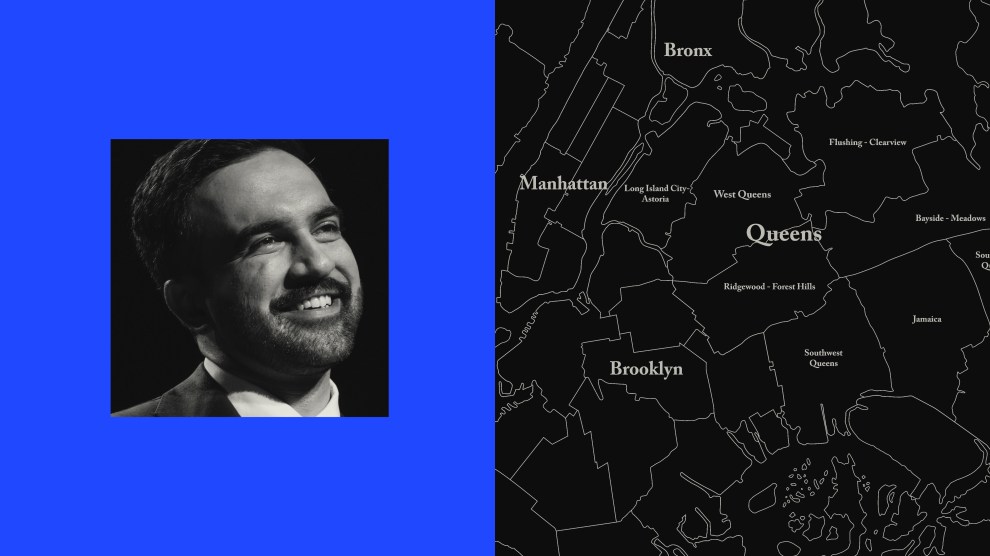

Mother Jones; John Lamparski/NurPhoto/ZUMA

Manhattan’s new Amtrak hub occupies the ground floor of an old Post Office sorting facility across 8th Avenue from Penn Station, and compared to the claustrophobic, sewage-strewn warren next door, Moynihan Train Hall feels like a revelation. Natural light floods through the elegant glass ceiling; at night, you can look up and see the lights of Midtown. It is nice in the way that generations of travelers have learned not to expect from New York City. I don’t want to be overly effusive here about a $1.6 billion project that does not improve train service at all. But Moynihan Train Hall is a lovely place to sit and wait for a train.

Or it would be, anyway, if you could sit.

Almost as soon as then-Gov. Andrew Cuomo opened the doors to the place in 2021, the complaints started rolling in about what was missing: a single bench. “Are We Ever Going to Get a Place to Sit Down in Moynihan Station?” asked Curbed. “Controversial Urban Design Opinion: Train Stations Should Have Benches Where the Fucking Trains Are,” said Hell Gate. In February, Rep. Jerry Nadler and a coalition of local elected officials wrote to Amtrak and the Metropolitan Transit Authority to demand “seats in the main hall where most passengers wait for their train”—and not just in the tiny waiting area further away from the tracks, that you need a ticket to enter. If you attempt to sit on the floor, security guards might ask you to stand up.

Two years in, there are still no more benches. There is, however, a mural of a bench. That is fitting. If what you are looking for is simply the idea of a public space rather than the thing itself, Moynihan is the place. Although officials have insisted that these kinds of design choices are aimed at facilitating the “circulation” of people, it serves the same function in practice as the station’s 1 a.m. closing time—to keep unhoused New Yorkers out.

The problem with Moynihan is not just a problem with Moynihan; it is merely a very expensive version of a problem that’s now endemic to public infrastructure. One of the animating principles of modern civic life is to make public resources increasingly inaccessible in order to prevent public resources from being used in the wrong way, or used at all by the wrong people.

There are examples everywhere you look. Laws punishing unsanctioned sitting are on the rise nationwide. New York City closed Washington Square Park at night after a group that included a co-founder of Facebook complained about the riff-raff. Seattle installed bike racks under an overpass in an attempt to make it harder for people to camp there (while also, perhaps, sending a message about how it values bicyclists). San Francisco spent half a million dollars to design a trash can that people can’t pick cans out of—and ended up with a bunch of trash cans people can’t put trash in. Last summer, officials in Lakewood Township, New Jersey cut down the trees that shaded their town square, in order to make it more inhospitable to homeless residents who had congregated there. The mayor explained to the Asbury Park Press that he was tired of those residents defecating in public spaces. That would not be as much of a problem, of course, if the town also had public restrooms. Instead of providing a baseline of services, governments devise far more burdensome and complicated systems to serve a narrower segment of people. Everyone is worse off from this.

Hostile architecture is not just about bathrooms and benches. Moynihan Train Hall is the brick-and-mortar manifestation of a way of thinking that permeates everything from politics to commerce. Arizona dumped shipping containers in a jaguar habitat to keep migrants from walking across the border. The logic is the same, from cashless businesses, to cities fast-tracking ride-share services but not bus lines, to a loan forgiveness program that rejects 99.7 percent of applicants: These are anti-public works, a reverse form of means-testing in which the benefits phase out the further down the income ladder you go.

The understanding that we can engineer public spaces to discourage the kinds of uses we do not want could go both ways. You can design streets to be more hostile to speeding cars and oversized trucks if you want to, just as you could house people for less than it costs to police and institutionalize them. But the exclusionary design is an expression of values, a crystallization of the hierarchy of worth.

What bothers me about Moynihan, more than just all the standing around, is the misplaced ambition it represents. “[T]his whole project is not about palaces by and for the people,” Aaron Gordon wrote for Vice not long after the station opened. “It is about ‘economic development,’ and the people get a little something for the trouble of selling off a massively valuable real estate asset that we used to own.” This is a throughline of a lot of the biggest projects in my city, and perhaps in yours too—politicians want a legacy, and whether it does the things you need it to do are a secondary concern at best.

A short walk west from Moynihan, Hudson Yards, an entirely new neighborhood built by the billionaire Stephen Ross with considerable help from the city, is a model community for one-percenters, centered on a piece of public art the size of an apartment building that had to be closed because people kept jumping off of it. That wasn’t the intended purpose of the installation, but then, what was its purpose and who was it for? In Queens, Mike Bloomberg built a $67 million swimming pool that doesn’t work. How can a swimming pool not work—and why did it cost $67 million? It helps if you understand that the mayor wasn’t building it for his constituents; he was trying to impress the International Olympic Committee. Moynihan is not even the only sparkling new transit hub in New York City that cost more than a billion dollars and lacked seating; it was, by one measure, the third such project in the last decade.

Even the stuff that works tells a story about the way things don’t. The new LaGuardia Airport—another splashy Cuomo-era project—is beautiful in all the usual ways, and also some uncanny ones. One of the most pleasant features, right next to the Irving Farms Coffee, is an indoor park, with leafy trees in planters ringed by comfortable metal benches. It’s possible to have a seat, and eat there too. You just have to buy a round-trip ticket to Boise first.

As usual, the staff of Mother Jones is rounding up the heroes and monsters of the past year. Find all of 2o22’s here.