Mill Creek near Washington, Kansas, was contaminated by crude from this week's Keystone pipeline rupture. US EPA

This story was originally published by Inside Climate News and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

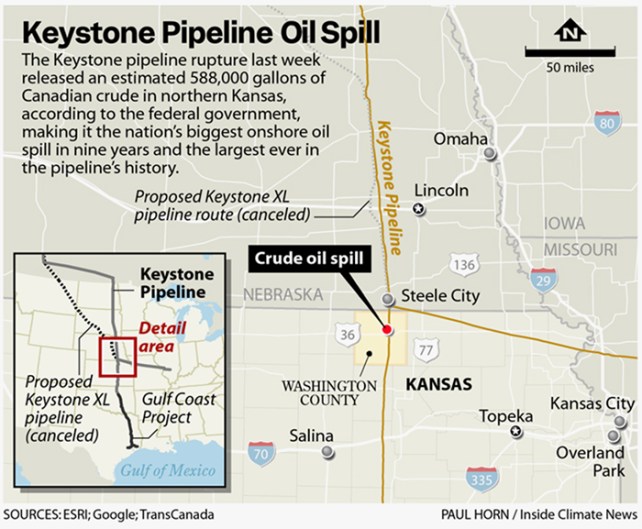

Crews continued to clean up the blackened banks of a northern Kansas creek Tuesday morning after a rupture in the Keystone pipeline last week released an estimated 588,000 gallons of Canadian crude—enough oil to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool. Translating to about 14,000 barrels, the incident is now the nation’s biggest onshore oil spill in nine years and the largest ever in the pipeline’s history, according to the federal government.

The pipeline, owned by Canada-based TC Energy, had previously leaked about 12,000 barrels of oil in 22 separate incidents since it began operating in 2010, according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report published last year.

In that sense, last week’s spill is historically significant in its own right. But pipeline safety experts and environmental advocates say the rupture is also an example of what’s at stake as federal lawmakers consider overhauling the environmental review process for energy infrastructure—a move that could fast track billions of dollars of new fossil fuel pipelines already in the process of being built across the nation.

Speeding that federal approval process has become one of the oil and gas industry’s top priorities in the next Congress. A streamlining proposal that was championed by West Virginia’s Democratic Sen. Joe Manchin was effectively blocked in the Democratically controlled House of Representatives. But with Republicans taking control of the House in January, the industry sees a new opportunity to advance what perhaps could be a more sweeping plan—one spearheaded by the GOP that could pick up fossil fuel-friendly Democrats in the Senate like Manchin, though approval there would most likely be difficult.

“Permitting reform is essential for us,” Frank Macchiarola, senior vice president of the American Petroleum Institute, said during a post-election forum in November.

Although much of the industry’s focus has been gaining approvals for natural gas pipelines, like the Mountain State Pipeline project in West Virginia favored by Manchin, the United States has more proposed oil pipelines in the works than any other nation, according to a recent analysis by the Global Energy Monitor in California. Some 1,800 miles of new U.S. oil pipelines—$8 billion worth of infrastructure projects—are in the works, mostly in the Permian basin of Texas.

It is part of a worldwide trend. Global Energy Monitor estimated that there currently are nearly 15,000 miles of oil pipelines proposed or under construction worldwide. That’s despite growing calls from the public to transition to renewable energy as a way to curb climate change, another major criticism from environmentalists who oppose Manchin’s push to overhaul the federal permitting process.

With the investigation ongoing, the cause of last week’s spill in Kansas is still unclear. But environmental groups have questioned whether it was related to a special permit the Keystone pipeline received from the Trump administration in 2017, making it the only oil pipeline in the U.S. that can run on a higher pressure than federal regulation allows. The pipeline has seen a notable uptick in incidents since that permit was issued, including three significant spills in the last five years.

In fact, last week’s spill now puts Keystone’s safety performance below nationwide averages, according to reporting by CBS News. And according to the nonprofit watchdog organization Pipeline Safety Trust, Keystone has averaged one significant failure per year during its lifetime.

Bill Caram, Pipeline Safety Trust’s executive director, said in an interview that Keystone’s track record raises serious questions about how and why the pipeline received its permits, and he worries that streamlining that process for the sake of saving the industry money could result in more spills like the one in Kansas.

“As far as permitting reform, I think the continued spills on this pipeline illustrate the risks pipelines pose, especially when there are construction and pipe integrity issues,” Caram said.

TC Energy didn’t respond to questions from Inside Climate News, but the company announced Monday that it has so far recovered about 2,600 barrels of crude. Much of the spill had flowed downstream into a nearby local creek that connects to the larger Missouri River basin. State and federal officials have said that the spill appears to be contained, and that so far there’s no evidence that drinking wells have been contaminated or that wildlife has been harmed.

Richard Kuprewicz, who has worked in the energy sector for 50 years and is president of the pipeline safety consulting firm Accufacts Inc., said it’s still too soon to draw conclusions about the cause and environmental impacts of last week’s spill. But the fossil fuel industry’s outsized influence on federal energy policy is well known, he said, and if the Keystone investigation reveals that last week’s oil spill was caused in part by a failure in the regulatory process, he hopes that Congress takes the issue seriously.

“I understand…on these multibillion dollar projects—with the time value of money—that yeah, we want to rush these things through,” he said. “But if it turns out that it’s something where there was a serious gap in the regulations, we need to address that.”

Pipeline operators have long touted their ability to run their infrastructure safely, often pointing to new technological advances that help them detect and mitigate leaks more quickly. But past reporting from Inside Climate News has revealed those technologies often miss the leaks they’re designed to catch, aren’t always built into projects in the first place and are susceptible to human error even when they are running properly.

Research also suggests that climate change itself poses a growing threat to fossil fuel infrastructure, including pipelines. More frequent and destructive extreme weather, rising sea levels and rapid temperature swings and melting permafrost in the Arctic can directly damage pipelines and other fossil fuel infrastructure that wasn’t designed with global warming in mind. A study published this year in the Journal of Marine Science and Engineering found that climate change can increase oil spill risks in the coastal and offshore regions. And our own reporting on the Trans-Alaska Pipeline shows how melting glaciers and shifting land mass pose a serious threat to that pipeline system.

For Kuprewicz, he hopes Congress weighs all these factors before they commit to making any major changes to the federal permitting process. “Congress needs to be very careful that they balance what’s good for the country, what’s good for the population,” he said. “Money can make a group of very smart people do incredibly stupid things. And time and time again, I see that.”

Marianne Lavelle contributed to this report.