One of the most intense races in Arizona this midterm election concerns public education: Republican Tom Horne, the architect of a state law used to ban Tucson Unified’s Mexican American Studies classes a decade ago, is back on the ballot hoping to get reelected as state school superintendent. He’s challenging incumbent Kathy Hoffman.

Horne, who lost a reelection campaign back in 2014, and whose signature law was later ruled unconstitutional and racially discriminatory, says he’s getting back into politics because, as he puts it, “liberals want our children to believe that America is a racist country.” This time, Horne, 75, has made Critical Race Theory a focus of his campaign. It’s on his yard signs—“Tom Horne. Stop Critical Race Theory.”—and his website, where he pledges to “stop cancel culture and promote patriotism.”

The anti-CRT language might be new, but the gist of Horne’s messaging hasn’t changed much in the decade since he last served as Arizona’s school superintendent. He sees conversations about race and historical context as intrusions on education. “My purpose to run is to get rid of the distractions, to focus on academics again, and get the kids’ learning up and their test scores up,” he told Education Week in September.

But for Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith, considered by many to be “mother of ethnic studies,” the discipline Horne and other Republicans so despise, discussions about race and historical context are crucial to education—and to the rights of the more than two million Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Latinxs who make up more than 30 percent of Arizona’s population. To Rubio-Goldsmith, a professor and humanitarian and the co-founder and former co-director of the Binational Migration Institute at the University of Arizona, history, especially the history of the country’s most marginalized people, has value beyond academics. Without a close look at the forces that shaped society today, “how can we change our future? How can we become full people in a country that puts us down?” Rubio-Goldsmith says. “How can we do that if we don’t know where we came from and how we got here?”

Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith at her home

Fernanda Echavarri

A vocal Chicana and a fronteriza, or woman of the borderlands, Rubio-Goldsmith was born in 1935 and grew up in the small Arizona mining town of Douglas. She was propelled by the social justice movements swirling around her in the 1960s and 70s—the large protests against the Vietnam War, the Black Power movement, feminism, César Chavez, and the formation of the Raza Unida Party—to build a college level educational curriculum “that included our history.” The ethnic studies classes she helped pioneer have been scrutinized, rejected, and questioned at every step of the way. “They must be very threatened if they have to keep coming at it,” she tells me. But that hasn’t stopped her from questioning whose humanity we, as a society and as a country, choose to value.

Today, at 87 years old and near the end of her career, Rubio-Goldsmith’s work is still urgently relevant. And while she has influenced a new generation of academics and activists to carry on her legacy, it’s on all of us to pay attention, especially as candidates like Horne threaten to make it go away.

That’s why I spent a handful of mornings in Rubio-Goldsmith’s colorful Tucson home earlier this year. We had first met about a decade ago when I was a reporter for the local NPR station, but we didn’t really know each other. Still, the first time I went to her house she greeted me with tiny fruit empanadas and a cup of tea. I told her that wasn’t necessary, but I know better than to try and stop a Mexican elder. And I also knew I needed to listen—just as we all do right now. The woman I got to know was kind, witty, a straight up badass in an understated way, and someone who has a way of making you feel seen—like really seen.

From a young age, Rubio-Goldsmith experienced firsthand what it meant to be categorized as “other” in the country she called home. The summer before she entered elementary school, Rubio-Goldsmith played with her neighborhood friends in the streets of Douglas until dawn. But when summer was over, she was sent to the school for Mexicans, despite being a US citizen who spoke English perfectly, while her best friend went to the Anglo school, which was nicer and had better teachers. That was the “first big thing that was really traumatic for me,” she tells me on one of our first visits, while seated in a green chair in her living room with her silver hair in a bun and her warm eyes peering out at me behind thin-framed black glasses. “We couldn’t be together in school. We were still playing together but it wasn’t quite the same anymore.”

A snapshot from 1940 shows Rubio-Goldsmith as a child on the right, with her cousin and her younger sister.

Courtesy Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith

Later, in an integrated high school, Rubio-Goldsmith got kicked out of a club because she wasn’t white, and heard her school bandmates get called Mexican slurs. It didn’t matter that Rubio-Goldsmith had a US passport—looking Mexican was enough for people to make her feel that she didn’t belong at times. “If I had been seen by the dominant group there as an American, I would have identified as American, but they identified me as a Mexicana,” she says. “I had to find who I was within, being a Mexicana, and I loved it, my mother made sure of that. But it meant that if I wanted a just society I would have to fight for it, not just for me but for all of us Mexicanos in this country.”

In 1953, she moved to Mexico City to attend Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México where her new Mexican friends called her the “gringa,” the American one. “I thought that was so weird, because I was so far from being a gringa,” Rubio-Goldsmith says as she shrugs her shoulders. Classic case of “‘ni de aqui, ni de allá”—the feeling of not fully belonging in either country.

For the next seven years, Rubio-Goldsmith threw herself into Mexico City’s artistic and political awakening, which in large part centered around the university. One night, she attended a film club screening of the 1954 film The Salt of the Earth, based on the 1951 labor strike against the Empire Zinc Company in Grant County, New Mexico. The film left her “utterly amazed,” she says. “It was the first time that I had seen ‘Mexican Americans’ in an English-speaking film that weren’t bandidos.” And seeing the similarities with her upbringing in a small mining town, “I began to see things in a different way,” she says. “It was like a light went on.“

After graduating from law school in Mexico City, Rubio-Goldsmith returned to the US in 1960, intent on changing the way her Chicano community was treated. After touring schools while working for an anti-poverty program in Pennsylvania, she decided the best way to tackle injustice was by transforming the education system. In 1970, after settling in Tucson, Rubio-Goldsmith and her husband, Barclay Goldsmith, were eyeing jobs at the newly launched Pima Community College, the first junior college in southern Arizona. Rubio-Goldsmith was offered an opportunity to prepare a history curriculum for the school. She had the idea to teach Chicano history, but the board would not allow it. “The use of the word Chicano was not an acceptable word for the more middle class of Mexican descent,” she says. “It was too political and we were seen as radical.”

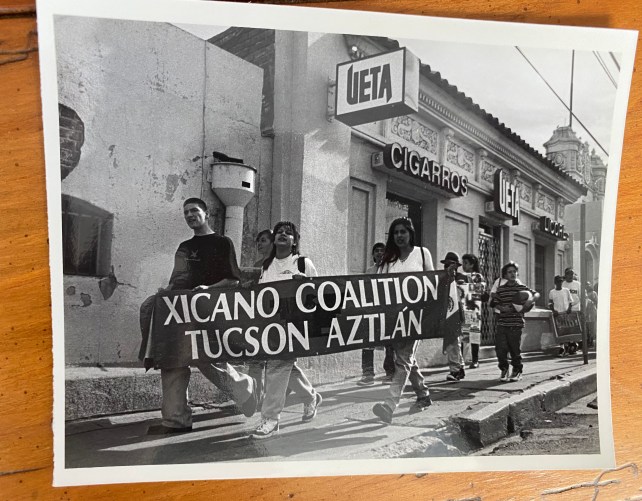

Rubio-Goldsmith took this photo of some of her students participating in a protest in Nogales, Mexico, in the 1990s.

Courtesy Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith

While she didn’t end up using “Chicano” in the title, Rubio-Goldsmith—who has self-identified as Chicana for decades—went ahead with teaching a Chicano history course, calling it “Mexican-American History” instead. Her classes quickly filled up. She often taught alongside Guadalupe Castillo—a fellow history professor who would become her lifetime friend and compañera—and they took some of the classes out of the college campus and into neighborhood community centers in lower-income areas with mostly Mexican residents, drawing more and more students. “There was a little building in South Sixth across the street from a very notorious bar, and they kept the key for our classroom in the bar, we had to go to the bar and get the key,” Rubio-Goldsmith recalls, laughing. “It was wonderful because we were right in the community.”

Rubio-Goldsmith noticed that her students were hungry for stories about people of the borderlands; there was a gap in historians’ documentation of Mexicans, Mexican Americans, and Chicanos after part of Mexico became the United States through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in 1848. “It’s as if we cease to exist,” Rubio-Goldsmith says. “Mexicans stopped studying us and Americans never began to study us, so it was a total vacuum.” Small details here and there about laborers or criminals were all Rubio-Goldsmith could find, so she spent countless hours in the mid ’70s trying to fill that void.

It wasn’t just the community college that took issue with Chicano history: When she approached the University of Arizona’s history department to see if the courses she was building for Pima would be recognized for transferable credit there, “they wouldn’t give me approval for the Chicano, Black, or Indian history courses,” though Latin American history was approved, Rubio-Goldsmith says. Some people at the UA told her those courses belonged in anthropology and had “no place in history,” or that Chicano history had no body of knowledge. “But I said we have to have them! I don’t know what we’re going to do, but we have to have them.”

A decade later, Rubio-Goldsmith joined the faculty at the University of Arizona as a professor of the recently formed Mexican-American Studies and Research Center (which wouldn’t become a department until decades later). Seeing the positive impact the popular classes had on college students, Rubio-Goldsmith and Castillo moved to get a version of the curriculum to high school students. “Things took years and it required a lot of community push to make them happen,” she says. “It wasn’t easy.” Community activists kept up the pressure, and finally, by the late 1990s, Tucson Unified School District, Arizona’s second largest, started a Mexican-American Studies program that gained popularity. According to a later analysis, the classes succeeded in getting more Latino students to graduate from high school and to be more engaged in school.

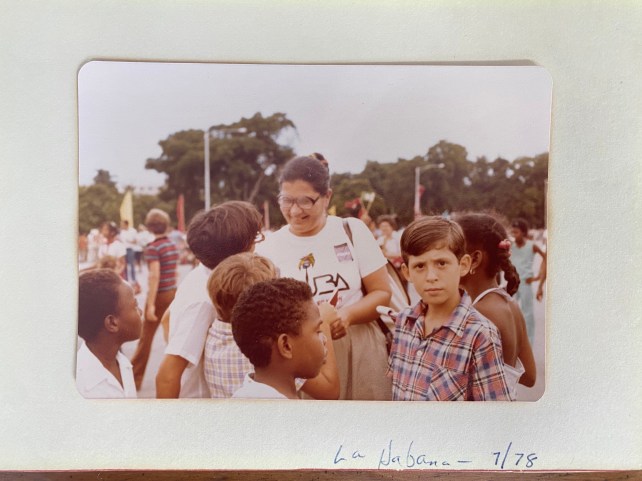

Rubio-Goldsmith while on a trip to Cuba in 1978

Courtesy Raquel Rubio-Goldsmith

Sean Arce, a former student of Rubio-Goldsmith’s and a co-founder of TUSD’s Mexican-American Studies program, says Rubio-Goldsmith’s Mexican American Studies classes at UA were instrumental in allowing him to understand his own mother and the struggles her generation faced while trying to assimilate in US society (Rubio-Goldsmith’s curriculum focused especially on women’s history). Arce has taught at a couple of school districts in Los Angeles, including LA Unified, and now trains teachers on ethnic studies. California now has a high demand for the instruction—in 2021, it became the first and only state to make ethnic studies a high school graduation requirement (schools will be mandated to offer courses starting in 2025).

Despite the success of Tucson’s program, or perhaps because of its success, Arizona’s government went after it. During the height of the anti-immigrant, anti-Mexican, Governor Jan Brewer “show me your papers” era of Arizona, Republican state lawmakers fought to destroy the program, eventually shutting it down in 2012 (the ban was later overturned in 2017). Many of the books used in ethnic studies classes were banned, including 500 Years of Chicano History, Rethinking Columbus, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and Luis Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway. In some instances, school officials carted the books out of classrooms while classes were in session.

Tom Horne, who in 2011 had just left his post as state school superintendent to become Arizona’s attorney general, said the Mexican American Studies classes broke a new state law he was behind because they “promoted the overthrow of the US government” and “resentment” towards white people—a suggestion he reiterated on the campaign trail in 2022.

As the program she had helped establish found itself under threat, Rubio-Goldsmith could only think, “we have to fight this.” And many Tucson high school students did: They commandeered a school board meeting by chaining themselves to board members’ chairs to prevent them from voting to shut down their classes. In a later public school board meeting, students spoke passionately about how distraught they were to see a program they loved so much under attack. It felt personal. One student testified that when he started reading the books in his first Mexican-American Studies class, “I just wanted to read more and more and I’ve never been a book reader, that’s never been me.” Many students teared up when they shared how much Mexican-American studies classes improved their self-worth, and made college finally seem like a reachable goal.

Rubio-Goldsmith knew part of the students’ resolve to protest traced back to what they had learned in their ethnic studies classes. “All these experiences that have been shoved aside as inferior, or non-existent… they go away,” after taking the classes, Rubio-Goldsmith tells me. “They suddenly find who they are, and that’s what education is.”

The current movement both to attack and defend ethnic studies and CRT across the nation, Arce says, has been informed and inspired by the Arizona struggle. Arce says Rubio-Goldsmith, and the way she stood by the Tucson school district and its students in the fight to keep the classes alive a decade ago, has been “transformational for hundreds of us.”

During our chats, Rubio-Goldsmith’s laugh starts to become familiar. It’s hard to describe, but it’s high-pitched, contagious, and comes with lots of eye squinting. Her warm energy radiates and translates into a socially distanced hug. But something shifts when we start talking about deaths at the border. She gets raw and angry—each of her words heavier than the last. “There’s something very wrong when you have a border where for over 100 years, people have been dying, and it’s the people coming from Mexico or it’s Mexicanos living here,” she says, her voice rising. “That is what we have been living with, and nobody wants to talk about it!”

Rubio-Goldsmith’s efforts to make ethnic studies a part of Arizona’s curriculum paved the way for another one of her passions: documenting migrant deaths. “Looking at that history and those inter-ethnic relationships has allowed me to think through how [so many deaths] could happen,” she says, “and how it is that we are here in terms of immigration today.”

On a hot summer day in 2001, Rubio-Goldsmith was listening to a Spanish radio station when the hourly news segment came on. What she heard made her turn the radio up: The bodies of at least 14 men and teenage boys had been found in the Arizona desert. They had died from exposure in the unbearable heat after their smuggler abandoned them while trying to cross the border, the deadliest crossing on record at that time. Rubio-Goldsmith had been volunteering with Coalición de Derechos Humanos, an organization that helped undocumented folks in Southern Arizona, and she and her colleagues had been seeing an increase in phone calls from families whose loved ones had gone missing after attempted crossings. But something about this incident—which would inspire Urrea’s novel The Devil’s Highway, one of the books later banned in Tucson high schools—rattled Rubio-Goldsmith. “I was just so upset at the scene. How could it be possible!?”

The newscaster said the bodies would be taken to a mortuary in Tucson, so first thing the next morning, Rubio-Goldsmith drove out to the mortuary, where she waited in the parking lot as a handful of other cars full of “ordinary people” who heard what happened and “wanted to express their sorrow” pulled up. They weren’t allowed into the mortuary, so they prayed for people they didn’t know, standing outside under what little shade a eucalyptus tree provided in the scorching morning.

“See, what we have is a killing field,” Rubio-Goldsmith says, referring to the Arizona desert. “And we don’t know how many people are dying, we don’t know how many people are missing, and I’ll tell you why—because there is no national way of counting.” In her home, Rubio-Goldsmith pays homage to those lost: She displays a two-foot statue of an angel decorated with hundreds of thin multicolor ribbons, each one representing a death in the desert.

For much of the early 2000s, Rubio-Goldsmith and her compañera Isabel Garcia were “going crazy trying to find some research or something empirical that we could take to Congress,” Garcia tells me, to sound the alarm about what was becoming a mass casualty phenomenon. “We were easily dismissed without hard data or research papers.” So Rubio-Goldsmith set out to compile that data.

Rubio-Goldsmith at a table with male colleagues from Pima Community College’s Intercultural Committee in 1970.

Fernanda Echavarri

She focused on Pima County, where the medical examiner’s office was pioneering work in properly documenting migrant deaths. By 2004, Rubio-Goldsmith had helped found the University of Arizona’s Binational Migration Institute, which focused on researching the impact that immigration enforcement has on communities of people of Mexican descent. The following year, she published the organization’s first report, Funnel Effect, which showed a massive spike in the number of bodies found each year from 1991 to 2005. The key takeaway was drawing a direct connection between the rise in deaths and the US government’s “Prevention Through Deterrence” policy, which intentionally pushed people to cross in remote and dangerous areas of the border, hoping the risk of dying would be enough of a deterrent to stop migration. Not only was this a flawed assumption that failed to meet its goal, it was the main reason more than 650 people lost their lives in the desert from 2000-2004 in Southern Arizona alone. (At the time, almost 80 percent of all deaths along the entire US border happened in Arizona.)

“Raquel made sure we remembered the humanity” while working with these cases, says Daniel Martínez, her former student who is now the co-director of the BMI and has authored several of its papers on climate impacts on border mortality and the radicalization of immigration policies. “This person was somebody’s brother, mother, or tío or tía. She made sure we never lost the face of these numbers, and that’s very powerful.”

Other students and mentees of Rubio-Goldsmith I spoke with shared similar experiences of how much she insisted on not becoming numb to the suffering of human beings. The remains of more than 3,741 people trying to cross the border have been found in the Southern Arizona desert alone since 2000. Last year had the highest number on record, with 226 bodies recovered. And 2022 is on track to become the deadliest year on record along the entire US-Mexico border. “It’s worse than I could have ever imagined it,” she tells me.

On my last visit to Rubio-Goldsmith’s house, she mentions that later that day she will receive an award from the Mexican consulate at an outdoor event. She tells me that it’ll be a corrido contest in Tucson’s Westside, so of course I have to go.

Corridos are traditional Mexican songs that could be described as folklore ballads telling stories of struggles, familial love, death, oppression, heartbreak, and the occasional neighborhood drunk. As I wander in later that night, about 100 people, mostly Mexican and Mexican American, are in attendance as the sun starts to set. I hear Spanish, English, and Spanglish. Some contestants from the neighboring Mexican state of Sonora wear cowboy boots and hats and a group of teen girls in a folklorico group are impeccably dressed, without a hair out of place.

Mexico’s Consul Rafael Barceló Durazo takes the stage to welcome everyone and introduce the Distinguished Mexican Award for Rubio-Goldsmith. With Rubio-Goldsmith by his side, he says that her life and professional work “reflect the evolution of geographic limits between Mexico and the United States: the challenges, hopes, and understanding of human rights throughout the decades.”

Rubio-Goldsmith steps up to the microphone with the help of her cane and humbly says, “I’m not going to talk long… I want to mention that all the work that’s been done has never been an individual work, this is an award for our community.” She ends her speech by asking attendees to “please, if you haven’t signed our “Justice for All” petition, please do so because we need your support.” (She had been working on a ballot initiative effort to provide legal representation to people in immigration court in Pima County.)

The crowd cheers for Rubio-Goldsmith and as I look around I can see how she has inspired us to gather strength from our people’s suffering and to fight against injustices. She has impacted generations of Chicanx and Latinx students who will continue to “do the work,” and around me in this crowd are people who are doing some of that work. And she has influenced a whole new crop of historians to make sure we don’t forget about it. “I’d say if Raquel is the mother of ethnic studies, then she’s also the grandmother of the new generation of Chicano-Latino scholars,” says Martínez, her former student. Many of those scholars and teachers, including Arce and author and historian Lydia Otero, grew up learning about their own history because of Rubio-Goldsmith’s efforts to accurately represent the past to better understand our present.

As the sun sets, Rubio-Goldsmith and her husband continued watching the corrido performances and clapping joyfully after every act. It’s powerful to see this celebration of Mexican heritage at a time when extremely divisive politics seem to easily strip away the humanity of non-white people. I’m reminded of something Rubio-Goldsmith said to me at one of our meetings: “This is such a hard time right now because the things that we were fighting for 50 years ago are maybe worse, or are going back to being the way they were, so it’s a little bit disheartening,” Rubio-Goldsmith said. “However, I have great faith.”