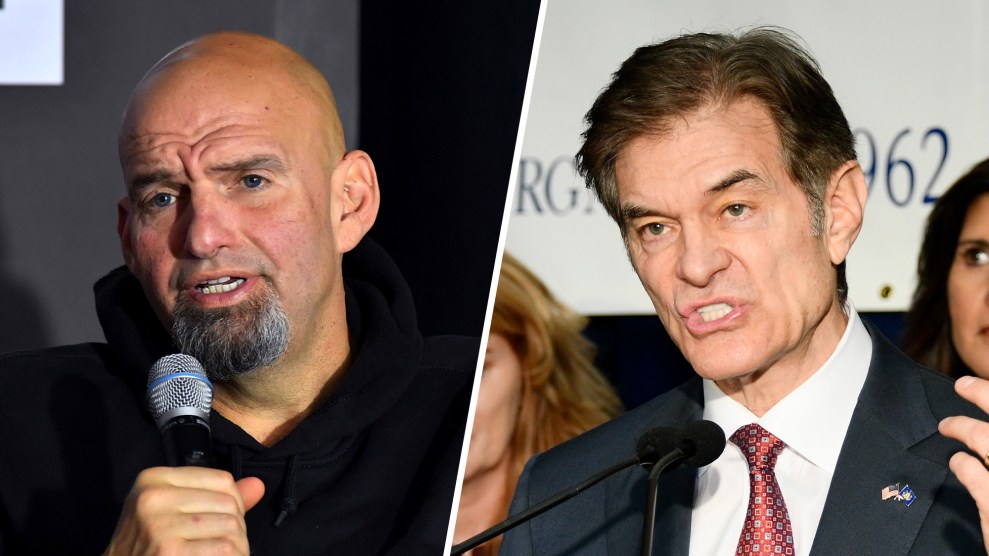

Aimee Dilger/SOPA/ZUMA; Bastiaan Slabbers/NurPhoto/ZUMA

If there’s one thing Dr. Mehmet Oz wants you to believe, it’s that his opponent Lt. Gov. John Fetterman is soft on crime.

Oz, a celebrity talk-show host turned Republican politician, has hit this point over and over again as he attempts to close the gap in an increasingly tight race in Pennsylvania that could determine whether Democrats or Republicans take control of the Senate next year. In September, he put up a billboard in the town where Fetterman formerly worked as mayor, depicting images of toilet paper (“soft on bottoms”) and an adorable puppy (“soft on skin”) alongside Fetterman (“soft on crime”). “John Fetterman wants ruthless killers, muggers, and rapists back on our streets, and he wants them back now,” one ad for Oz, underwritten by the conservative group MAGA Inc, warned. From mid-August to mid-September alone, Republicans spent upwards of $10 million on TV spots depicting Fetterman as a far-left radical who allowed crime to spiral under his watch, according to the Philadelphia Inquirer. “John Fetterman is one of the most dangerous Democrats,” Donald Trump said at a recent rally. “One of the most fringe, far-left freak shows.”

But though Fetterman may not seem like a typical political candidate, with his tattooed arms and tendency to wear hoodies and shorts to campaign events, he’s far from lackadaisical about crime, and he’s not as leftist on questions of policing and public safety as Republicans have made him out to be. In fact, though he and Oz obviously differ a great deal in their beliefs, their stances on these issues have more in common than you might expect. The ads against Fetterman “are misleading,” says David Harris, a law professor at the University of Pittsburgh. “John is no radical.”

If stopping crime has only recently become a talking point for Oz, who jumped into the Senate race after many years of hosting The Dr. Oz Show, it’s long been a top priority for Fetterman: It was a primary reason why he became a politician in the first place. In 2005, after stints working at an insurance firm and then as a teacher, Fetterman successfully ran for mayor in the borough of Braddock after two of his former students were gunned down, as my colleague Abby Vesoulis wrote in a recent deep-dive about the candidate. Two weeks after taking office, he personally showed up at another homicide scene, that of a pizza delivery man who’d been killed during a robbery. “I think it’s time we do something” to make the street safer, Fetterman told reporters at the time. In the coming years, Fetterman hosted gun buyback events and helped establish youth enrichment programs to deter kids from crime, and even tattooed the dates of homicides on his forearm to keep the issue top of mind.

He also kept showing up at crime scenes, which helped convince some residents that he cared about their safety. “I remember when there was a shooting one time and he jumped in his car and he almost beat the cops there,” Joe York, a construction worker in Braddock, recently told a reporter for WESA, the NPR affiliate in nearby Pittsburgh. At moments, Fetterman’s zeal for crime-fighting arguably went too far, like in 2013, when, after hearing gunshots, he grabbed his shotgun and chased after a Black man on a run in the neighborhood named Christopher Miyares, whom he falsely suspected of pulling the trigger. (Years later, Miyares seems to have forgiven the candidate, writing to the Philadelphia Inquirer that “Mr. Fetterman and his family have done far more good than that one bad act or action and, as such, should not be defined by it.”)

If you examine Fetterman’s overall record as mayor, “it was very clear that he was trying to direct attention onto these problems” of gun violence, “that he wanted something done about it,” says Harris, the law professor. Gun violence dropped after Fetterman took office, with no homicides in Braddock from mid-2008 to mid-2013, though they later crept back up. (Pittsburgh’s NPR affiliate has a great analysis of how overall crime shifted there, and whether Fetterman should take credit or blame.)

On the question of law enforcement funding, Fetterman has also been fairly moderate. Spending for the police department rose in Braddock during his mayoral term, from 18 percent of the borough’s budget when he took office in 2006 to nearly 25 percent in 2013 and then 21 percent by his last year in the position. While Fetterman may not agree with Oz’s claim that funding the police is a way to fight back against “radicals and the extreme left,” he has talked about wanting to ensure that law enforcement have the money they need to do their job (even as he stresses the importance of police oversight). “It was always absurd to defund the police,” Fetterman told the news site Semafor in October. “From my own experience I’d say, anytime you have fewer police, you’re going to have more crime.”

There are some key differences in the way the two candidates view criminal justice reform. After leaving the mayor’s office, Fetterman became the state’s lieutenant governor in 2019, and one of his duties was chairing the Pennsylvania Board of Pardons, a position that allowed him to recommend the early release of incarcerated people. Oz has repeatedly blasted Fetterman for recommending, along with the other members of the board, 50 commutations of life sentences, compared with just 11 in the prior two decades. Fetterman “consistently puts murderers and other criminals ahead of Pennsylvania communities,” Brittany Yanick, Oz’s communications director, said in a statement.

As head of the pardons board, Fetterman focused on giving second chances to people who received lengthy sentences for second-degree or felony murder, a crime that does not necessarily entail killing someone. Brothers Lee and Dennis Horton, for example, were convicted in the early 1990s after picking up a friend in their car who, unknown to them, had just fatally shot someone in a robbery. In 2020, Fetterman recommended that the governor commute the brothers’ life-without-parole sentences, and he subsequently hired them to work on his Senate campaign. “More than 1,000 people are sitting in jail right now on what amounts to a death sentence despite never having taken a life,” Fetterman said in press statement last year, noting that Pennsylvania requires judges to issue mandatory life-without-parole sentences in these cases. “Any reasonable person who looks at the unfairness of these sentences will acknowledge the need for change.”

Releasing some of these people from prison is unlikely to lead to more violence, according to experts who study crime. Researcher Ashley Nellis of the Sentencing Project, a nonprofit that pushes for fewer life sentences, pointed out in the same press statement that many of the prisoners serving life without parole in Pennsylvania were teens when they committed their offense, have served decades behind bars, and are now elderly. Their imprisonment is “costing the state millions despite their very low risk of ever again committing another crime,” she noted.

“There’s no Willie Horton that [Fetterman] voted to pardon,” Larry Ceisler, a Democratic political analyst and public affairs executive in Philadelphia, told me recently, referring to the 1987 case of a man who committed violence in Maryland while on a furlough from prison, and whose story was weaponized by Republicans in the presidential election the next year. “If there was a Willie Horton” in Pennsylvania, “we would have seen [ads about] Willie Horton millions of times.”

Though Oz has taken every opportunity to oppose Fetterman’s stance on second chances, he has hinted that he’s not entirely against efforts to reduce the number of people behind bars. In an attempt to sway Black voters in September, he said he supports the First Step Act, a federal law that passed during the Trump presidency and aims to lower the federal prison population. “[W]e can go further in analyzing federal penalties that are unfair, and reform our system of justice to make sure equal protection under the law is upheld,” Oz noted in a policy statement.

And on at least one other issue where he and Fetterman diverge—gun control—they have some common ground as well. Though Oz opposes any restrictions on Second Amendment rights and Fetterman supports universal background checks and red flag laws, they both tout their personal experience with guns: Oz recalls that his father taught him to hunt when he was a boy, and Fetterman says he’s currently a gun owner and has “been around guns my whole life.”

Oz’s insistence that Fetterman is too radical to keep people safe is not reflected in Fetterman’s history, but Oz seems to be betting that hammering these points will be a political winner. He’s not the only Pennsylvania politician who thinks so: State lawmakers now pushing to impeach Philadelphia District Attorney Larry Krasner, a progressive, over his record on gun violence, are operating under a similar calculus. These “politicians—who we must assume are focused on their own political survival—view the crime issue as a dangerous one for them politically,” Blake Hounshell, who edits a New York Times politics newsletter, wrote recently of the impeachment effort. Oz has repeatedly tried to link Fetterman with Krasner. Most Republican candidates in Pennsylvania are campaigning heavily around crime, “but Oz is doing it really intensively and almost to the exclusion of anything else,” says Harris, the law professor.

This emphasis on crime can be misleading, he says. Though gun-related homicides spiked drastically in the early pandemic across the country, reaching record numbers in Philadelphia, other types of violence in Pennsylvania remain at levels far below the crime wave of the 1980s and early ’90s, and below national averages, according to FBI data from 2020. (The FBI did not estimate crime trends in Pennsylvania in 2021 because so few police departments there submitted data.) Shootings are also largely concentrated in specific neighborhoods, disproportionately affecting people of color. Oz’s crime ads, though, “are not meant for the people who are really at risk for this kind of violent crime,” says Harris. “They’re meant for the people it doesn’t affect, people in the suburbs, in safe neighborhoods. And it’s all designed to scare them.”

Recent polling suggests that voters nationally do care immensely about crime, even if they don’t live in areas gripped by high rates of violence. But former public defender Insha Rahman, who helps lead the nonprofit Vera Institute, says research by her organization suggests that people respond best to political messages that spell out solutions rather than stoke fears. She cited Fetterman as one of the Democratic candidates nationally who have done a good job laying out their proposals, with a series of ads recently by law enforcement talking about his ideas to deliver public safety. “The question is,” she says, “is it too late in response to the onslaught of attacks?”

Meanwhile, Oz has said relatively little during his campaign about his own solutions to tackle crime. In mid-October, just a few weeks before the election, he put out a “crime-fighting agenda” that focuses on securing the Southern US border and disrupting drug cartels, “maintaining cash bail for violent offenders,” and giving cops the resources to “prosecute crimes today, not tomorrow,” among other measures. “I’m surprised that more people aren’t looking at Oz and saying, ‘What the heck has he ever done’ other than be on TV?” says Harris. “You want to be a TV doctor, great, but how does that qualify you—what is that experience worth when it comes to making policies about how to make families safer? He’s been allowed to not really have to answer for that. Instead we get, ‘Fetterman is too radical.’ We get, ‘Everything is dangerous.'”

But could the fearmongering be enough to derail Fetterman, who started with a double-digit lead, but whose campaign efforts took a hit after he had a stroke in May? The race is narrowing: A recent Monmouth University poll showed that 48 percent of respondents would at least “probably” vote for him, compared with 44 for Oz, while an Emerson College poll showed Oz with a slight lead.

“The race was always going to tighten. That’s just the nature of Pennsylvania,” says Ceisler, the public affairs executive in Philadelphia, who notes that the battleground state has a long history of heavy campaign spending and close Senate races. He doubts that crime will be a determining factor in the outcome next week.

“Whether it turns out to be the leading edge that sways a lot of people,” says Harris, the law professor, “time will tell.”