By midmorning on an early October day in 2021, the parking lot is full at the Trust Women clinic in Wichita, Kansas. Cars have been pulling in steadily for hours under a slate sky, droplets from the unpredictable autumn showers pimpling their shiny surfaces. Some parked cars hold men, waiting, the glow of a phone casting their faces in a blueish light.

A tall wooden fence surrounds the clinic to protect patients from hostile gazes. Black iron gates frame the entrance to the lot. Protesters pace back and forth, pleading with entering cars to stop and writing down license plates when they refuse. A plastic baby doll that has clearly seen better days rests in a weather-worn bouncer, its purpose to prompt a deep sense of maternal responsibility and guilt. A yellow-and-white box truck also looms, engine off, across the street. It belongs to the Kansas Coalition for Life, and it is splashed with gruesome images of torn, fragmented fetuses and a proclamation: “EVERY Abortion is an Act of Violence! Violence is NOT the Answer.” Next door to the abortion clinic is a crisis pregnancy center, simply called Choices Medical Clinic.

Black-and-white Texas license plates flash in the sun as they turn in to the Trust Women lot. For the past month, Texans had lived under an abortion ban that made the procedure illegal after roughly six weeks’ gestation. In Texas, for all intents and purposes, Roe was already dead, and this Wichita clinic, along with others in the Midwest and the Southeast, had been feeling the strain of an influx of patients. When the Texas ban went into effect, Trust Women saw 51 patients from the Lone Star State within that same month, compared with just one the month before. Trust Women’s sister clinic, in Oklahoma City, saw more, too; it added a procedure day. The Texas law encourages citizens to report anyone who may have done anything to “aid or abet” an abortion; physicians who provided abortion care risk a lawsuit and minimum fine of $10,000. One patient who called to make an appointment at Trust Women said she was less than six weeks pregnant but because cardiac activity was detected during her ultrasound, a clinic in Texas had turned her away. More Texas patients coming to Trust Women meant patients from other states were facing lengthy waitlists because of increased demand.

In less than a year, the Supreme Court will overturn Roe v. Wade, and more neighboring states, including Oklahoma, will clamor to become as hostile as possible to abortion, putting even more pressure on the Wichita clinic. But Trust Women is familiar with working under pressure. From 1975 to 2009, Trust Women was called Women’s Health Care Services, and it was helmed by Dr. George Tiller, one of the few doctors in the nation who offered abortion care in the third trimester. That clinic closed down when Tiller was murdered by an anti-abortion extremist. Today, friends and acquaintances of the man who killed Dr. Tiller still linger outside his former clinic. States have put large monetary bounties on the heads of those who can be proved to have “aided and abetted” abortion. It begs the question: How much longer before violence sparks once more?

Sophia Larson, a protester and member of Kansas Coalition for Life, stands outside the Trust Women Clinic.

Zoe Freilich

To enter Trust Women, patients must pass through a metal detector, helmed by a wizened security guard with a mischievous grin, usually following a joke that might have come out of the writers’ room of The Andy Griffith Show. Some patients indulge him, returning a smile; others stare blankly, unable or unwilling to muster the energy for banter, because what would be the point?

Around 10:30 a.m. on the day I visited last fall, there is a commotion near the front desk. A patient is weeping as she leaves the clinic, begging for abortion care, as the receptionist gently repeats that she’s over the state’s gestational limit of 22 weeks and they cannot help her. The patient is familiar; she’d come to the clinic before seeking birth control. Today her state-mandated ultrasound determined she was further along than she’d thought. Staff who know her from past visits weep with her and go through the list of clinics that could still help. None are in Kansas. They also reach out to abortion funds, trying to alleviate the financial burden. Still, everyone knows it will be an uphill battle. When she leaves, clinic director Ashley Brink comforts her staffers. “If you need a break, take it,” she advises. Instead, they make plans to check in on the patient the following week to see what other help they might offer.

Ashley Brink, clinic director of Trust Women.

Zoe Freilich

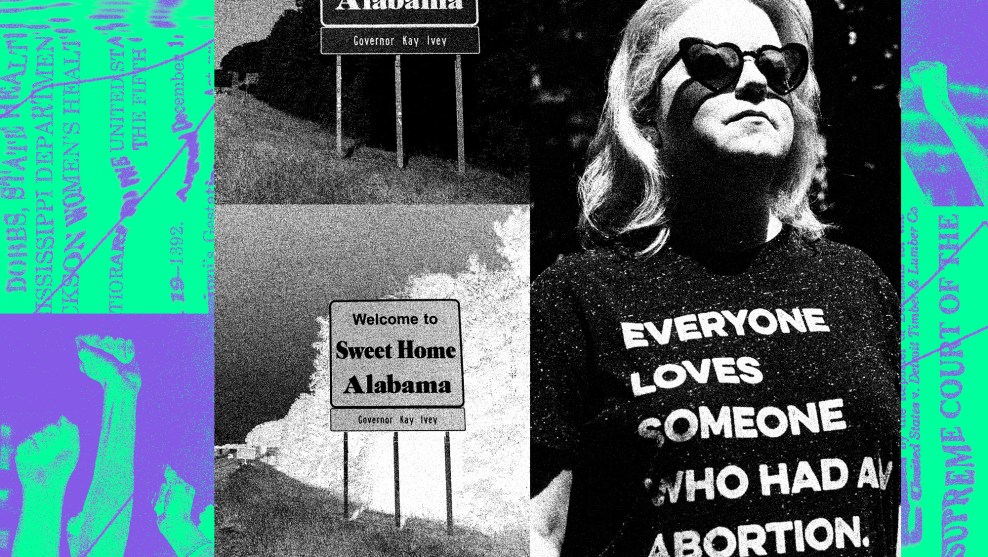

Brink, 31, knows that the staff at Trust Women are exhausted; she is, too. They have been seeing about 35 patients a day, twice the normal load. Today, two staffers call in sick. All the abortion providers are fly-ins; none of the physicians live locally. Brink’s fine brown hair is pulled hastily into a ponytail. She lives in scrubs, and most mornings she clutches a purple-and-gold coffee mug that says “Everyone loves someone who has had an abortion,” a nod to abortion storytelling nonprofit We Testify. A tattoo on her right arm says “Call Jane,” with a hotline number underneath; another on the same arm is a nod to The Handmaid’s Tale. It reads “Nolite te bastardes carborundorum”—“Don’t let the bastards grind you down.” Two-and-a-half months have passed since Brink began her job as clinic director, and her office bookshelves remain mostly bare.

When I ask Brink, who was raised in a small town in the northeastern part of Kansas, how she and the staff are doing, she laughs a little, shooting me a beleaguered look. “We’re here,” she says. “We’re seeing patients. We’re doing the thing, and everyone shows up every day ready to do this, and that’s more than I could ask, because it’s hard.” The pace of her days has only increased in the aftermath of Texas’ ban. “We could work providing abortions till midnight every night, but that’s not sustainable,” she says.

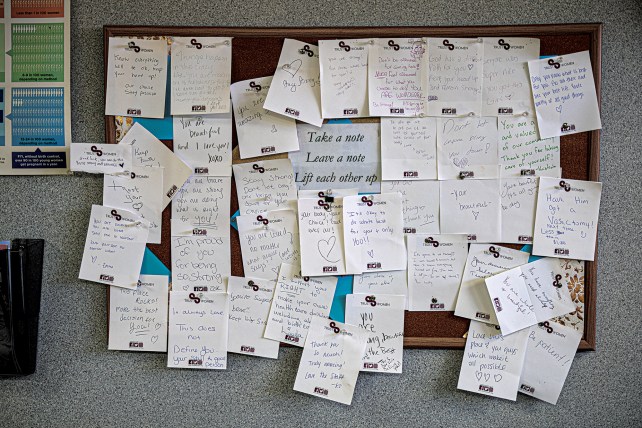

Despite all the added stress, or perhaps because of it, Brink and the crew at Trust Women have put a lot into trying to make the clinic seem less…well, clinical. A small fountain in the corner of the waiting room babbles, and the bathroom walls feature quotes from Dolly Parton: “If you want the rainbow, you’ve got to put up with the rain.” Another waiting room has a desk with pens and notecards for patients to leave words of encouragement for each other, which they pin to a bulletin board. Even the cavernous, sterile procedure rooms come with small adjustments: Lamps are dimmable, and the brown vinyl surface that patients lie on for their procedures is always referred to as a table, never a bed, so as to be sensitive to people who have experienced sexual assault. The result is a feeling of calm and safety amid a battle being waged outside.

When George Tiller first became a doctor, abortion care was not part of his vision. Tiller was preparing to exit the US Navy, where he was serving a tour of duty as a surgeon, and start a residency in dermatology when his parents, sister, and brother-in-law died in a plane crash in the summer of 1970. At 29 years old, he found himself responsible for his sister’s 1-year-old son and for his father’s sprawling family practice in Wichita. He and his wife, who’d go on to have three daughters, returned home with a six-month plan to put his family’s affairs in order and wind down his father’s clinic, but he soon realized there weren’t enough doctors in Wichita to take on his father’s patient load. He shifted to a three-year plan. “After I had been there for a little while, patients in the practice began to ask me if I was going to do abortions like my father did,” Tiller recalled in a 2001 interview. He was shocked; abortion was still illegal. “I was outraged. Why would these nice people say that he was a scumbag kind of a physician?”

Over time, he came to understand. He heard about a woman who came to his father for an abortion. His father had delivered two of her babies, and she was pregnant again, too soon after the birth of her last child; she begged him for an illegal abortion and he refused. She died soon after because when she was forced to seek care elsewhere, she found someone who was incompetent.

Tiller knew that loss must have devastated his father; it certainly seemed to change his convictions. When abortion became legal in 1973, the younger Tiller decided he too would provide the procedure in Wichita. At first, he offered abortions at a local hospital, Wesley Medical Center, but that ran about $1,000, and Tiller could do the procedure for $250 at his clinic. (Two other hospitals in Wichita, both Catholic, did not provide abortion care.) The former family practice became Women’s Health Care Services.

Tiller had a reputation for being exacting. He demanded perfection from himself and his staff, and anyone who couldn’t live up to that needed to get the hell out of the way. On his watch, there were no shortcuts. That’s not to say he was a saint—he could be belligerent, he had a mild savior complex, and he wrestled with alcoholism and drug use.

Early on in the days of legalized abortion, Tiller was among only a handful of doctors anywhere in the United States who provided abortion care later on in gestation, and he grew intimately familiar with the myriad ways pregnancy can go horribly wrong. Women who desperately wanted babies came to him under wrenching circumstances that forced them to terminate their pregnancies. But Tiller believed wholeheartedly that women knew what was best for their bodies and their lives, which inspired a motto that after his death became the clinic’s moniker: Trust Women.

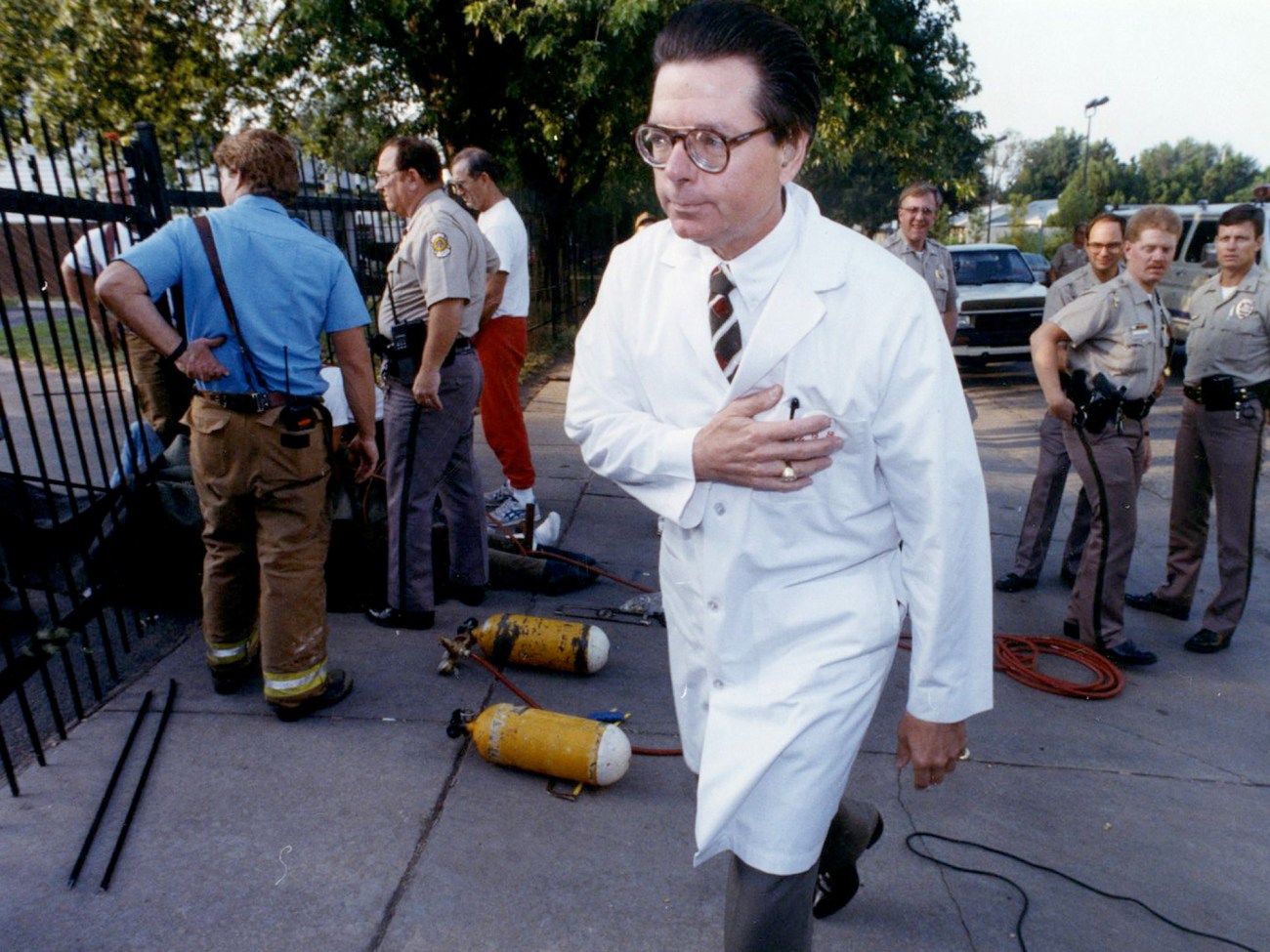

Dr. George Tiller outside of his clinic after four people locked themselves to the entrance of the clinic’s gates.

Richard Hernandez/Wichita Eagle/Tribune News Service/Getty

Krista, who now volunteers with Planned Parenthood in Memphis and asked to be identified only by her first name, was 15 when she and her mother sought Tiller’s help. She and her boyfriend had been sexually active, and while they used protection most of the time, it wasn’t readily available to the Illinois teens. It was 1985, and when she realized she was pregnant, she went into deep denial. It can’t happen to me. This can’t be happening, she told herself over and over. Finally, she summoned the courage to buy a pregnancy test. When she told her parents, the family was in agreement that she was much too young to have a baby. First, they went to Peoria to seek care, but Krista was turned away—she was too far along. Wichita was the only option.

Mother and daughter soon arrived at Tiller’s clinic. She remembers other patients, including a couple who’d lost a child in early infancy to a genetic abnormality. When they had discovered that their second pregnancy would have the same outcome, they decided they could not bear to watch a baby suffer all over again for the few days it might survive outside of the womb. Krista remembers a pregnant little girl the most, a few years younger than she was, maybe around 11 years old. The girl was Hispanic, and she didn’t speak any English; her face was contorted in terror. Together, this group had a counseling session with Tiller based on techniques he had come across in Alcoholics Anonymous.

For patients in the third trimester, Tiller preferred an abortion method that required an injection that stopped the fetus’s heart before miscarriage was induced. After the injection, Tiller would counsel his patients once more before dilating their cervixes, and in those conversations, he would also ask their wishes regarding fetal remains—some women wanted photos, others baptisms, and others simply wished not to have anything to do with what came out of their bodies.

As they waited in a nearby hotel for Krista’s labor to begin, Krista recalls a nurse stopping by to check on her. When the process began to reach its natural conclusion, they went back to the clinic. Tiller was kind and reassuring throughout her abortion. Before they left, he peered down at her through wire-rimmed glasses and told her that she reminded him of one of his daughters. “He very much believed that this was a health care issue, and very much believed that this made a difference in women’s lives,” she says. “And he laid down his life for that belief.”

Protests began in earnest in 1975, and they were fiery, fueled by outrage at the range of abortion care Tiller offered at his clinic. In 1986, not long after Krista went to Women’s Health Care Services for her abortion, a pipe bomb went off, causing more than $100,000 in damage. The perpetrator was never discovered.

Afterward, Tiller hung a sign saying “HELL NO! WE WON’T GO!” and installed extra security—bulletproof glass, the gate and fencing and metal detector, and armed guards, eventually including the same guard who still works there, who remembers Tiller as “a good man” who “didn’t have any fear.” Tiller began wearing a bulletproof vest.

That same year, Operation Rescue was founded, and it immediately ramped up the tactics of the anti-abortion movement. Its leader, Randall Terry, a self-described “former used-car salesman, hamburger flipper and teen-age marijuana user,” deployed strategies including civil disobedience to prompt mass arrests and intense harassment of anyone connected to an abortion clinic. In 1991, Operation Rescue organized the Summer of Mercy, a six-week-long protest focusing on George “Killer” Tiller, as they called him. It was the group’s largest and most lucrative effort, lasting 42 days, resulting in nearly 2,700 arrests, and bringing in an estimated $177,000.

As employees began to face targeted harassment, Tiller started issuing regular staff bonuses, which he dryly referred to as “combat pay.” Sometimes he would tell them that “the only requirement for evil to triumph is for good people to do nothing.” Occasionally, he would shout back at the protesters—he once told Terry that he was sorry his mother hadn’t aborted him.

A housewife and mother named Shelley Shannon, radicalized by a group that called themselves the Army of God and that told its members that murdering abortion providers was morally justifiable, took a bus from her home in Oregon to Wichita. It wasn’t her first act of violence—she’d already committed a string of clinic arsons, following instructions laid out in the Army of God handbook—but this trip would be different. She approached Tiller in the clinic parking lot as he was about to drive off in his 1989 Chevy Suburban. He thought she was going to hand him anti-abortion pamphlets, so he raised his middle finger. She shot him in both arms. He managed to get back inside the clinic, where his staff treated his wounds as Shannon sped off. A clinic staffer had the presence of mind to chase Shannon for long enough to jot down her rental car’s license plate number, and cops picked her up when she arrived in Oklahoma City to return the vehicle. The next day, Tiller was back at work, where he posted another sign outside: “WOMEN NEED ABORTIONS AND I’M GOING TO PROVIDE THEM.”

Sixteen years later, a slender, bald, white man named Scott Roeder—also a member of the Army of God—homed in on Tiller’s church as the place where the doctor would be most vulnerable. Twice, Roeder went to Reformation Lutheran Church for Sunday services, but couldn’t find Tiller. On Roeder’s third visit, Tiller was serving as an usher. Roeder, head bowed, approached. He pulled a gun from his pocket and shot the abortion provider point-blank in the head in his house of worship. Tiller did not survive.

It’s been more than a decade since Tiller was murdered, but at Trust Women, which reopened and rebranded under his protégé Julie Burkhart in 2013, the past has a habit of lingering outside the gates.

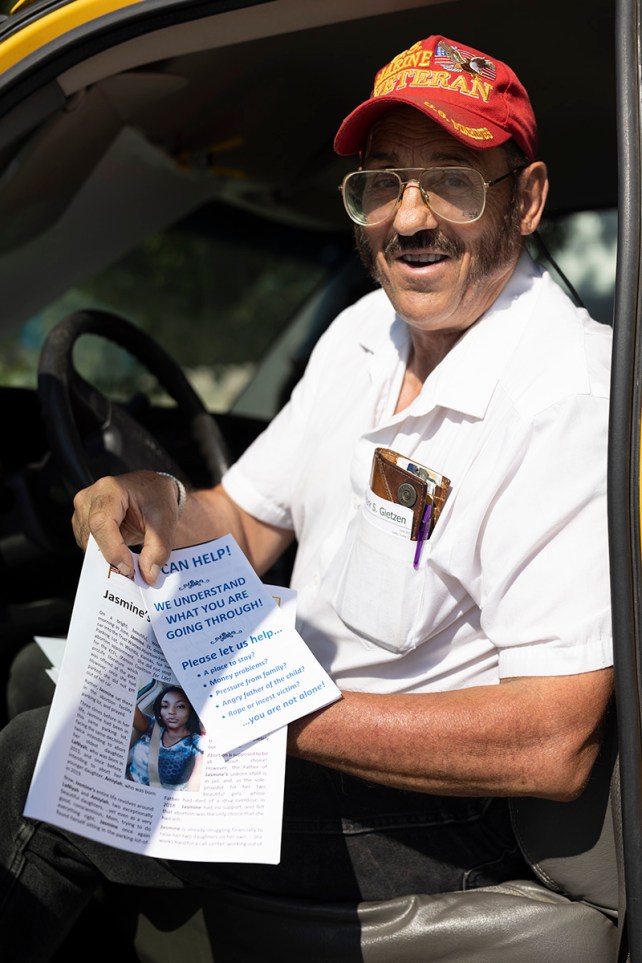

As morning begins to fade into midday, the rain has stopped, though thick gray clouds remain. Two graying white men stand by a sagging card table that holds anti-abortion pamphlets and a curling pile of paper with an impressive list of license plate information. One of the men, Mike Hagan, tells me he’s been setting up outside the clinic since 1992. He strikes me as earnest and thoughtful, if paternalistic, open to engaging with my questions and criticisms. They are both affiliated with Kansas Coalition for Life, which is led by Mark Gietzen, who has protested at the clinic since 1978. During Tiller’s tenure, Gietzen had a fondness for reaching out to Fox News personality Bill O’Reilly with inflammatory “tips” about Tiller’s work—which in no small part is what made Tiller such a high-profile target. O’Reilly discussed Tiller on his show dozens of times in the years before Tiller’s murder, saying the doctor was doing “Nazi stuff,” suggesting he was covering for pedophiles, and comparing him to al-Qaeda. Gietzen also cultivated a deep network of activists across the Midwest who had no problem making the trek to Wichita for protesting.

Mark Gietzen has been protesting at the Trust Women clinic since 1978.

Zoe Freilich

Hagan says Kansas Coalition for Life has made a commitment to financially support each mother and “youngster” who is saved, through the child’s 18th birthday. This pledge is advertised on the pamphlets he distributes, but the mechanics of the program are unclear.

Hagan is not bombastic, like many of his peers on the sidewalk. He acknowledges that, as a man, he cannot truly understand what it’s like to be pregnant, or to give birth. For this reason, women who work as “sidewalk counselors,” as he calls them, are more effective. Still, he feels he cannot sit on his hands while what he sees as a life-and-death situation plays out. He has to enter the fray, but he’ll do it in his way—quietly, gently.

We continue to talk. Cars interrupt our conversation every now and then, prompting Hagan to scramble, imploring them to stop, scribbling down their license plates when they roll into the lot.

He admits that his note-taking is likely intimidating for people. “I’d be worried about it myself if somebody did [the same],” he says. But, he shrugs, it’s public information, and the intent is to provide documentation in case anything goes wrong inside the clinic. They fancy themselves an asset to law enforcement: Hagan explains that if someone inside dies or is maimed from a botched abortion, their information could help identify the victim. The record also gives them standing in court, he says, because it shows “commitment and responsibility.” “Nobody ever looks at this stuff ever,” he promised, “until something bad happens.” (It bears repeating that abortion is an extremely safe, common, and simple medical procedure.) He believes, at the very least, that “something bad” used to happen with some regularity. “When Tiller was operating here, you know, they’d often have a botch situation and they’d take it to the hospital and try to hide it, put all kinds of pressure on these people, pay ’em off so they didn’t say anything negative,” he tells me, though there is no evidence of this.

About a dozen abortion opponents gather in front of Dr. George Tiller’s clinic in 2007, to launch a 77-hour prayer vigil.

Larry W. Smith/AP

If Hagan has indeed been a presence at the clinic since the ’90s, he knows that recording license plates has not been harmless. In 2004, for instance, Operation Rescue organized a campaign to harass any clinic worker to such a degree that they would quit their jobs. It used the license plate numbers of the employees to make sure they had the right homes before they began picketing or digging through their garbage. A 2004 Rolling Stone profile of Troy Newman, who heads Operation Rescue, details what happened to administrative assistant Sara Phares: “Before long, protesters from Operation Rescue showed up at her house. They parked a tractor-trailer across the street, plastered with twenty-foot-long images of dismembered fetuses. From its speakers came the kind of sweet, tinkling music that lures children from their backyards in pursuit of Dreamsicles. One protester, a somber man in a tan windbreaker with a three-foot crucifix thrust before him, performed an exorcism on Phares’ front lawn, sprinkling holy water on the grass to cast demons from the property.”

Newman was not the first to decide that tracking license plates was a useful tactic, or that intimidating doctors and clinic staff was a good approach. Indeed, it was popularized by anti-abortion activist Joseph Scheidler in his 1985 manual, Closed: 99 Ways to Stop Abortion. Scheidler is known as a “godfather” of the anti-abortion movement and its direct-action approach to abortion protest. He is also largely credited with identifying doctors as a “weak link” of abortion and trying to convert them to the “pro-life” side. When that didn’t work, he set about organizing harassment campaigns similar in spirit to those of Operation Rescue. In short: Scheidler walked so that Newman could run. (Newman is also an adviser for Kansas Coalition for Life, whose fetus-decorated truck sits outside Trust Women.)

Around lunchtime, a woman in purple scrubs with long brown hair and an air of excitement approaches where Hagan and I are talking. She is Jennifer McCoy, a so-called sidewalk counselor, and she’s ready to celebrate.

Earlier, Hagan had flagged down a van approaching the clinic and passed the driver some pamphlets. The driver worked for a rideshare, but McCoy had recognized that he was on “our side,” she says, thanks to a vanity plate on the van reading “Blessed,” and the man’s shirt, adorned with imagery from a crowdfunded Christian TV show called The Chosen. The van pulled back out shortly after, and McCoy says she beckoned the driver to roll down his window, and he did. “Can I do anything to help you?” she asked. Peering into the van, she could see a woman in the back, reading the leaflets she’d given them, which insist, “If you are pregnant, you are already a mother. No one can change that. An abortion decision will only make you the mother of a dead child—forever.” The driver told McCoy that they were going to Choices, the crisis pregnancy center, instead. McCoy has come over to tell Hagan the good news. “That’s what we do,” Hagan says, looking intently at me.

McCoy’s account seems to have sharpened Hagan’s conviction. There’s an edge to his voice that wasn’t there before as they discuss the windowless design of the clinic building, which, combined with the fence, does give the place the feel of a fortress. The conversation quickly turns gruesome, and I can’t shake the feeling that they are watching to see if I will blanch. “They used to have an incinerator and they’d take the baby parts and incinerate ’em, and we would walk out here and you would actually get the little black flecks and the aroma,” he says matter-of-factly. “They had to stop it eventually because too many people associated it with the Holocaust.” (The anti-abortion movement commonly compares the Holocaust and abortion.) McCoy adds that incinerations would take place at two o’clock in the morning, but the protesters would still be on the sidewalk, holding 24-hour prayer vigils. “After the ash would build up on the roof, when it would rain, the gutters, the downspouts would shoot out ash,” she says. “It’d be foamy and always bothered me.” (The clinic did once cremate remains if patients requested it, but this recounting strikes me as hyperbolic.)

McCoy adheres to the Catholic faith. A mother of 12 children—only one was adopted—she has a girlish voice, and she’s scrappy as hell. She has a bright, friendly demeanor, but she is not harmless. At 24 years old, she was convicted of attempted arson for trying to set fire to two clinics in southeastern Virginia—placing a lit flare through the mail slot at Peninsula Medical Center for Women in Newport News, and, 15 months later, breaking into the Tidewater Women’s Health Center in Norfolk, pouring out two gallons of kerosene, and setting it aflame. When she appeared before a judge, she had a cross of ashes on her forehead in observance of the beginning of Lent. “I didn’t want anyone to get hurt, and I didn’t want children to die,’’ she told the court. “If the babies don’t get justice, why should anyone else?” She served two-and-a-half years in prison and reportedly paid $1,335 in restitution.

When I ask about the arsons, she talks instead about how a Clinton administration law infringed on her First Amendment rights by making it a federal crime to block entrances to clinics through force, the threat of force, or physical obstruction—a law that was partly a response to Operation Rescue’s tactics in Wichita. “There were a lot of the abortionists that were doing damages to their own buildings to collect the insurance money, because they were sometimes having problems with business, and so there were a lot of unsolved crimes,” she claims. “There were people doing things. I’m not saying there weren’t. One of my best friends burned down like seven abortion clinics when nobody was in them, and he’s a minister.” She chuckles.

She tends to ramble, but the upshot of her anti-abortion origin story is this: She became pregnant by her JROTC instructor when she was 16 and he was in his 30s, married and with children. She wanted to keep the baby, but her mother coerced her into an abortion by telling her they were going for a simple obstetrician appointment. “There was no one on the sidewalk that day,” she says. “Had there been one person outside telling me that that was an abortion clinic, I never would have gone in.”

Mark Geitzen’s truck as seen from the Trust Women

Zoe Freilich

That’s kept her protesting clinics for 30 years. Early on, she would enter clinics, pretending to need a pregnancy test, usually with her infant in tow to help persuade other women in the waiting room that motherhood was feasible and well worth it. Sometimes, patients followed her out of the clinic to hear more. “I feel like this is where God wants me to be,” she says. “And I don’t want any one of these people—not one of them—to ever have to go through everything that comes along with going in this place.”

McCoy’s words, I think, are genuine. What’s harder to swallow are her actions, and the company she keeps. A photo of her surrounded by her children at a clinic protest in 2009 shows them decked out in black T-shirts that proclaim “visualize abortionists on trial.” It’s a slogan from the Nuremberg Files, a website created by militant anti-abortion activist Neal Horsley, where he published the names, addresses, and other personal information of roughly 200 abortion providers, who were referred to as “baby butchers.” Names of those who had been murdered, like Tiller, were struck through—“the butchered,” the site said—and names of those who had been merely wounded were listed in gray. Nuremberg Files dossiers were connected to the deaths of three abortion providers, including Dr. Barnett Slepian, gunned down at his home in Amherst, New York. Hours after Slepian’s death, his name was crossed off the list, though Horsley insisted he had no prior knowledge of the murder, saying he merely updated the website after seeing the news online.

The Nuremberg Files explained itself thusly: “A coalition of concerned citizens throughout the U.S.A. is cooperating in collecting dossiers on abortionists in anticipation that one day we may be able to hold them on trial for crimes against humanity. We anticipate the day when these people will be charged in perfectly legal courts once the tide of this nation’s opinion turns against the wanton slaughter of God’s children.’’

The site was shut down in 2002 after a court deemed it a “true threat,” overriding any free speech claims. Even so, versions of it can still be found.

McCoy is also a fan of the Reverend Donald Spitz, who operates the website for the Army of God, which explicitly supports the murder of abortion providers. She told a Vice News reporter in 2016 that she counts him among her friends, calling him “quite a character.” The two had met at a clinic in Norfolk where she was trying to “save” a friend who was seeking an abortion. “When I pulled into the driveway, he was there,” she told reporter Matt Ramos. “He thought I was going to go to the clinic. I didn’t know anything about the inner workings of pro-life work. He’s truly the one who showed me. I have always felt called to be at the clinic, but he showed me how.” Spitz touts Tiller’s murderer, Roeder, and Paul Hill, who shot and killed another abortion provider, Dr. John Britton, and his bodyguard, James Barrett, as “American heroes.”

After Roeder was arrested, McCoy’s name came up as one of his frequent visitors in jail. The morning of Tiller’s funeral, McCoy showed up, as usual, on the sidewalk by the clinic. She held a sign that read “george tiller—murderer not martyr.”

One of the Trust Women operating rooms.

Zoe Freilich

Notes left for patients inside the Trust Women Clinic.

Zoe Freilich

When I visited Trust Women nearly a year ago, the “sidewalk counselors” and other protesters were low on the list of worries for staff. Brink told me that providing abortion care—“killing babies,” as the folks outside would put it—is not the tough part of her job. “The hard part is listening to the stories and hearing what [patients] went through to get here,” she says. “The hard part is listening to them cry because of them feeling harassed by the protesters and the emotional toll that that took on them. And we face that every day coming into work.”

Now, of course, everything has changed. Thanks to an abortion ban passed in May, Trust Women’s Oklahoma location stopped providing abortions, making the Wichita clinic one of the last that remains open in the South and lower Midwest. In late June, after the Supreme Court released its ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, Trust Women started getting calls from people all over the country seeking help. “We had patients calling us from waiting rooms where they had appointments in other states, saying, ‘My appointment just got canceled. Can I come to you? How soon do you have an appointment?’” Brink says. Others were scared and confused about what the new laws meant for them: Could they go to jail if they’re traveling from a state where abortion is illegal? Could they be arrested? With state laws rapidly changing and the specter of prosecution now perpetually overhead, the answer is not always cut and dry. “We can’t tell them no,” says Brink. “You take a risk at this point.”

And an August ballot initiative, backed by anti-abortion groups, to exclude abortion protections from the state constitution has helped put the Trust Women clinic back in protesters’ crosshairs. “There are murmurs that we should expect a Summer of Mercy–type protest, given the history and where we live,” says Brink, who worries that violent anti-abortion extremists from out of state will descend, as they did 30 years ago. “It’s anti-abortion folks that have closed clinics in the states where they live and that are like, ‘Now where to?’ There will be people out here hoping to be standing outside of the clinic every day until we stop seeing patients or shut our doors.” (On August 2, voters overwhelmingly rejected the amendment to the state constitution, preserving abortion rights.)

The staff is doing their best to prepare—communicating regularly with local police as well as FBI and US Marshals, implementing new security measures, and seeking advice on how to double down on safety. The building “has a lot of scars,” says Brink. “I wish we didn’t have to be resilient. The anti-abortion movement has made it as such. They’ve made us victims, and they continue to harass and scare us.”

Adapted from Becca Andrews’ No Choice: The Destruction of Roe v. Wade and the Fight to Protect a Fundamental American Right, which will be published by Public Affairs in October.