Over the past four decades, private equity has become a powerful, and malignant, force in our daily lives. In our May+June 2022 issue, Mother Jones investigates the vulture capitalists chewing up and spitting out American businesses, the politicians enabling them, and the everyday people fighting back. Find the full package here.

After 16 years at the helm of Houdaille Industries, CEO Jerry Saltarelli wanted out. Since 1941, he’d poured his heart and soul into the company, starting out as a young lawyer and moving up the executive ranks. As CEO, he’d helped the company transform from a manufacturer of bumpers and shock absorbers into a nationwide construction and machine tools conglomerate.

With the company on solid footing, he was ready to retire, but there was a problem. Houdaille—cash-rich and with minimal debt—was the kind of company in vogue with the corporate raiders of 1970s Wall Street, and the New York Times declared that a takeover might prove “irresistible.” This would likely lead to restructuring and layoffs—bleeding the company of its value and tossing aside its way of doing business. Saltarelli wanted none of that. All he wanted was a way to sell his stake while keeping Houdaille independent, doing right by his colleagues, and protecting his legacy.

As he pondered his predicament, Saltarelli got a phone call from an unfamiliar trio of bankers. Jerome Kohlberg Jr., Henry Kravis, and George Roberts, friends from their time engineering deals at Bear Stearns, had started investment bank KKR just two years prior. They presented Saltarelli with a plan that they said could check all the CEO’s boxes: a leveraged buyout, or LBO. Saltarelli had to admit he’d never heard the term.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

KKR arranged a meeting with Houdaille in Fort Lauderdale, Florida, where they explained how an LBO would work. Institutional investors would lend them money based on Houdaille’s healthy cash reserve, enabling KKR and partners to buy up all the company’s shares and take it private. Houdaille would easily pay that debt back in four to five years, they said, thanks to the magic of corporate tax write-offs: Through some clever accounting, they could help Houdaille push off paying almost all corporate income tax for years, savings the company could use to pay off the debt it would incur during the buyout. By the time Houdaille had to pay Uncle Sam, the debt would be under control, and KKR would take the company public again, but at a much higher share price. Thanks to this plan, they could immediately offer Saltarelli and investors around $40 per share, about double what Houdaille was trading at. Not only would Saltarelli get his wish, but he’d make a hefty profit.

When Saltarelli agreed to KKR’s terms, it was historic: At the time, leveraged buyouts had only been applied to a few smaller companies worth less than $100 million. The Houdaille deal was worth almost four times that. Both Houdaille executives and the KKR financiers were set to come out of it nicely: According to journalist Max Holland’s 1989 book about LBOs, Saltarelli got around $5 million in cash ($20 million in today’s dollars), plus a retirement package, and new CEO Phil O’Reilly’s salary reportedly almost doubled. Baked into the deal were also annual management fees that Houdaille would pay to KKR (ranging from $646,000 to $1.3 million in today’s dollars), plus 1 percent of the total transaction cost for putting the deal together, and 20 percent of any capital gains accrued by KKR’s partners in the deal, which the industry calls “carried interest.” KKR kicked in as little as $1 million toward the buyout, which cost around $380 million, nearly all of it financed with debt that Houdaille alone would be responsible for repaying.

Within a few years, however, the American machine tool business went south, and Houdaille found itself drowning in its debt. Soon, KKR divested seven divisions of the company, eliminating 2,200 jobs. Then it borrowed even more money, put the debt on Houdaille’s tab, and used it to engineer a handsome buyout for the LBO’s initial investors who now wanted out. A year later, KKR sold Houdaille to a British firm, which sold all but one of Houdaille’s remaining divisions back to KKR, which used them to form a new company, IDEX. Houdaille died, yet the investors who’d killed it walked off with millions and called it a success: “All of the Houdaille ‘constituents’…fared well in the LBO,” declared a report commissioned by KKR. Just like that, a new kind of financial monstrosity was born.

Houdaille “was a wake-up call,” says Eileen Appelbaum, co-director of the Center for Economic and Policy Research. Wall Street firms, she says, were giddy at the discovery that they could load companies up with debt they’d never be responsible for paying down themselves and take an ample cut of the proceeds that came from stripping a company bare—and it was all legal.

“The public documents on that deal were grabbed up by every firm on Wall Street,” a principal at an investment firm told the New York Times in 1987. “We all said, ‘Holy mackerel, look at this!’”

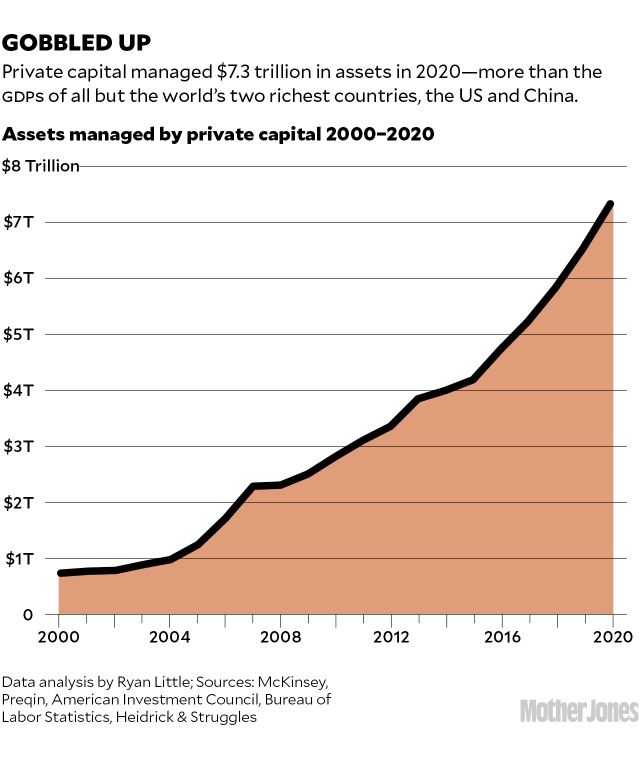

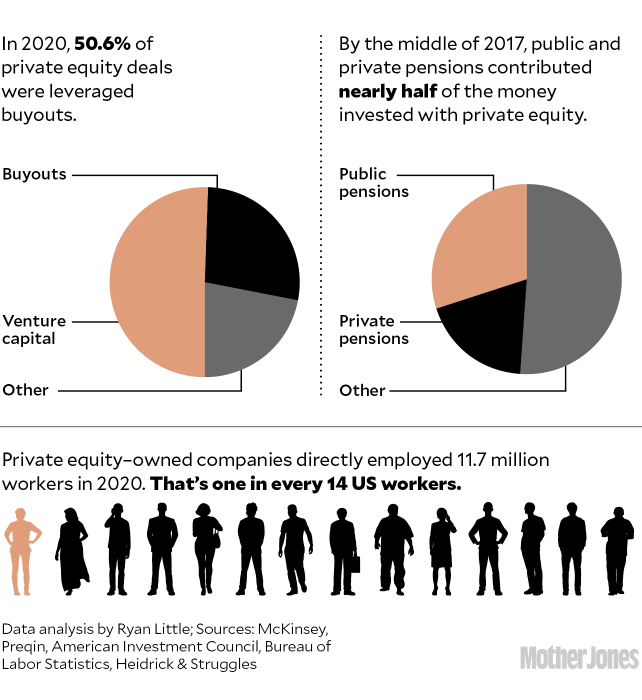

In the four decades since, investment firms that execute buyouts like Houdaille’s have expanded their grip on ever more pieces of civic life. Buoyed by LBOs and other forms of financial engineering, they have come to be known as “private equity” because they invest in transactions that are walled off from the public markets. In just a few decades they’ve bought up everything from dental offices to international call centers to Taylor Swift’s sorrowful ballads and mined them all for profit. Private equity’s favored methods for taking over companies have been back in the news this spring, thanks to Elon Musk’s $44 billion LBO of Twitter, where Musk has himself played the role of a private equity firm, securing billions in debt that he plans to load onto the social media company. Covid-19 did not slow private equity’s rise: In 2020, the private equity sector generated about $1.4 trillion—about 6.5 percent of the United States’ GDP, and a jump from two years prior, when it was 5 percent of GDP. Private equity firms also managed $7.3 trillion in assets in 2020—roughly the value of Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, and Tesla combined. Nearly 12 million workers—one in every 14 employees in the United States—collect paychecks from companies run by private equity.

That private equity is gorging on the US economy is something of an open secret. While reporting for this package, I heard from friends and colleagues who’ve eyed the new private equity owners of their doctor’s office, their fertility clinic, or their apartment building with a mix of skepticism and fear. I got a letter informing me that the electric and gas provider in my home state of Rhode Island—a local, independent company—was about to be purchased by a company heavily invested with a private equity fund based in Manhattan. But what most of us probably don’t know is how this juggernaut came to be. What forces made it this profitable to financialize the basics of Americans’ lives? And just how worried should we be about our private equity–controlled future?

In the popular imagination, private equity is often portrayed as a vulture, or some other scavenger that feasts on the sick and dying. Gross but unavoidable. But the bulk of the work done by modern-day private equity firms is not to finish off sick companies, but rather to stalk and gut the healthy ones. This type of predation is the result of 50 years of policies that have prioritized the profit-making of a few over the wellbeing of many: a corporate world that grew accustomed to valuing shareholders over everyone else, a penchant for siding with executives over unions, and a legislative establishment loath to enact strict regulations on the financiers whose donations fuel their campaigns. In short, a toxic soup of regulatory inertia and corporate greed.

For a long time, corporations worked in the plain way that you’d imagine they should work: They created a product or provided a service, and if they did a good job of it, they turned a profit. Houdaille, for example, grew to be a valuable company by making first-rate car parts. Simple enough.

But a confluence of factors in the 1970s flipped that model on its head. Suddenly, the value of a business was measured less by how well it served its customers, and far more by the profits it reaped for its investors. University of Chicago economist Milton Friedman helped propel this change with a 1970 manifesto in the New York Times. Corporations, he wrote, need not worry about “providing employment, eliminating discrimination, avoiding pollution and whatever else.” They were accountable to the wallets of their shareholders: nothing more, nothing less. “There is one and only one social responsibility of business—to use its resources and engage in activities designed to increase its profit,” Friedman added.

Historians deemed the resulting shift the “shareholder value revolution.” As rising stock prices became paramount, a raft of new ways to pump them up followed: first the kinds of hostile takeovers that Saltarelli had feared, and later the leveraged buyouts that KKR used his company to pioneer.

Soon, businesses came to be viewed less as productive enterprises and more as bundles of assets to be bought, sold, and endlessly manipulated for financial gain. Rather than doing the hard work of investing in new value—innovative products or fresh approaches to societal problems—financiers began focusing on extracting existing value, again, and again, and again.

This ideological shift soon collided with a human one. In August 1981, about 13,000 air traffic controllers went on strike to demand better pay and reduced hours. In violation of laws barring government workers from striking, they walked out of airports around the country, grounding much of American air travel. Within two days, President Ronald Reagan fired almost all of them rather than cede to their demands.

Reagan’s power play laid the groundwork for a decade of anti-labor activity that depressed union power at the exact moment when corporations were in the midst of their shareholders-first transformation. Appelbaum and Cornell professor Rosemary Batt explain in their book, Private Equity at Work, that as Wall Street salivated over the enormous gains of the Houdaille LBO, the backlash against labor made it easier for the budding kings of private equity—KKR, Blackstone, and Carlyle—to engineer buyouts that sacrificed employees for yet another megabundle of management fees and carried interest. By 1989, such firms had put together more than 2,000 leveraged buyouts valued at more than $250 billion. It was a moment—a wild, money-making one for Wall Street, and a sobering one for the broader public, who glimpsed this world through fictional private equity overlords like the greed-loving Gordon Gekko or Pretty Woman’s Edward Lewis.

Many companies that had dived headfirst into the LBO money pot were meeting fates like Houdaille’s, either disbanding or filing for bankruptcy in record numbers. Congress and state legislatures held hearings, and several states passed legislation to make leveraged buyouts harder to execute. But that was a minor speed bump. In 1999, private equity firms successfully lobbied Congress to repeal the Glass-Steagall Act, undoing restrictions on risky investing by commercial banks that had been erected in the wake of the Great Depression. Armed with an even bigger pool of money to play with, institutional investors began allocating more to high-risk, high-return investments executed outside the public markets—officially spawning the term “private equity.”

After the dot-com bubble burst in 2001, the country entered a recession. For private equity, this proved to be a boon. Lured by promises of higher returns than they could get from sluggish bond and stock markets, pension funds began to flock to private equity firms and soon became their biggest investors. University endowments, sovereign wealth funds, and the rapacious wealthy all followed suit. Flush with all this capital, private equity embraced LBOs with a new fervor, going from $62 billion invested in 547 leveraged buyouts in 2001 to $775 billion spent across more than 2,500 buyouts in 2007.

The 2008 financial crisis eventually provided another windfall. Public rage focused on the banks that had enabled the Great Recession and the plundering of millions of Americans’ savings, and lawmakers crafted a sweeping bill, the Dodd-Frank Act, aimed at regulating them. But private equity firms weren’t seen as the bad guys, so the bill’s provisions targeting them were lighter. Congress did ultimately require private equity firms worth more than $150 million to register with the Securities and Exchange Commission and file general reports with the agency about their operations. But critically, those reports—unlike those filed by other financial institutions or public companies—are confidential. As banks were forced into relative transparency, Dodd-Frank secured private equity’s position as a place for rich people to park and build their fortunes outside of public scrutiny.

Explosive growth followed. In the last decade, private equity has taken control of more than 80 retailers, leading to the loss of 1.3 million jobs. A firm named for the Ayn Rand character Howard Roark has bought up so many restaurants that it now employs nearly 1 million fast-food workers nationwide, all while successfully lobbying Congress to kill legislation mandating a $15 minimum wage. Private equity incursions into real estate have left no form of housing unscathed, driving up the costs of both owning and renting any type of house or apartment or mobile home. They’ve bought up for-profit colleges, driving down graduation rates while increasing student debt. They’ve sought gains in the obscure crevices of our mutual existence, from contact lenses to port-a-potties to ketchup. And they’ve enveloped the health care sector, including hospitals, dermatologists, ophthalmologists, veterinarians, hospice care, and nursing homes, often leading to increased medical costs for patients and a drop in the quality of care. A 2021 study from a group of business school professors found that private equity ownership of nursing homes increased their Medicare billing and upped the mortality of patients by 10 percent—about 20,000 lives across the 12-year period they studied.

It bears noting that not all private equity acquisitions kill jobs, product quality, or companies. In the best cases, private equity takes a faltering business and improves it—a win-win for all involved. But study after study confirms that the bad results eclipse the good ones. A 2019 report found that private equity purchases of companies resulted in the loss, on average, of 4.4 percent of the companies’ jobs—and as high as 16 percent for certain types of acquisitions. In the latest example of this, Elon Musk announced plans to cut jobs at Twitter as he pitched banks on lending more than $20 billion toward his leveraged buyout of the social media company. Multiple studies have also found that private equity buyouts drive down wages at acquired companies, even when productivity increases. Private equity firms wreak this havoc while charging their investors steep fees—about $230 billion between 2006 and 2015, according to one estimate. That money has created a new class of multibillionaires but not delivered particularly impressive returns: Private equity firms haven’t beat the US stock market since at least 2006.

As they’ve acquired this enormous wealth, private equity leaders have not been shy about wielding it to push rules that make them even richer. In 2020, prompted by GOP megadonor and Blackstone CEO Stephen Schwarzman, then-President Trump’s Labor Department issued a ruling allowing private equity firms to invest the money held in 401(k) accounts, subjecting the retirement savings of Americans to higher fees and the risk of, at worst, losing their entire investment. Biden’s campaign at the time called the move “another example of President Trump putting the interests of Wall Street ahead of American workers and families.” But in December of last year, Biden’s Labor Department quietly issued its own ruling, leaving the Trump-era changes intact.

This aversion to stricter regulation of private equity means its dominance will only grow, says Appelbaum, and so will cutting costs and corners and jobs to extract financial gain. The evidence can be seen in small inconveniences: the decision by a PE-owned hospital, for instance, to buy the cheapest, roughest paper towels for nurses who wash their hands dozens of times a day. Or in broader indignities: a PE-owned hospice care company that provides fewer visits to dying patients by medical assistants who are cheaper to employ, but for whom the company can bill Medicare the same amount as for a visit by a nurse. And then there is life-altering damage: medical bills that gut family finances all because private equity firms have bought up so much of the health care sector that they can charge virtually anything.

“Right now, they can do whatever they want,” Appelbaum says. “And that means quality of life deteriorates for everybody.”