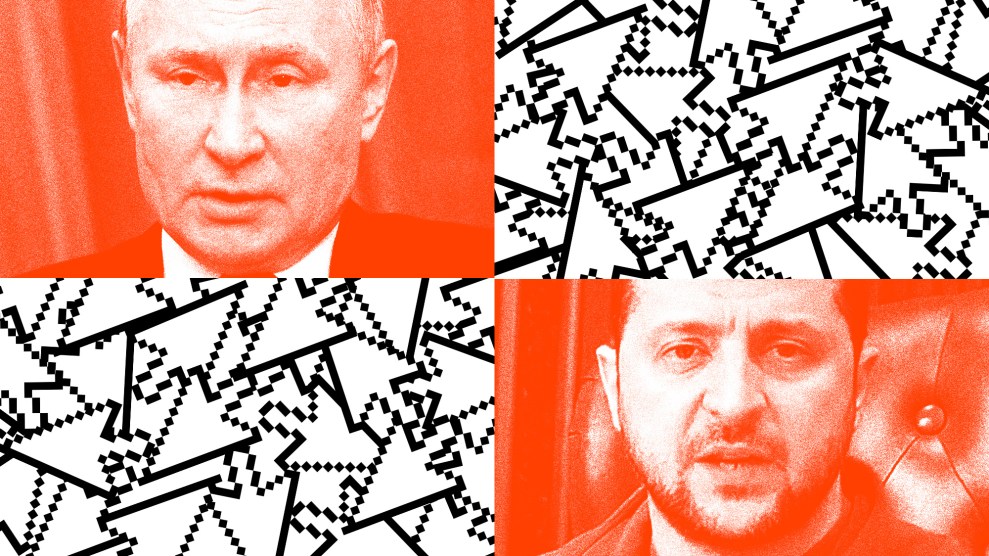

Photographer Peter Turnley has recently traveled in and out of western Ukraine, documenting both the heartbreak and the inspiring moments of people in flight. The French American photographer has documented violent conflicts across the world for more than three decades, and he has spent his career highlighting the realities of the human condition, most recently in the Covid-19 pandemic. Turnley shared with Mother Jones his recent diary entries from Ukraine, which he was posting daily on Facebook, and which we’ve edited together here, alongside his photographs.

Day 1, March 7

I flew today from Paris to Krakow, Poland, then boarded a train to Przemyśl on the border with Ukraine. On the train, I sat next to Liuba, 42, who had fled from Zaporizhzhia, Ukraine, near the site of the nuclear power plant that had been bombed. She explained to me she felt very guilty to leave her parents there, and she is very proud of her husband who has stayed to fight.

I sat across from Andre, 30, who had been working in Poland and has a wife and 5-year-old daughter. I asked him why he was heading back to Ukraine, and he told me, “I am returning to throw Molotov cocktails to defend my country.”

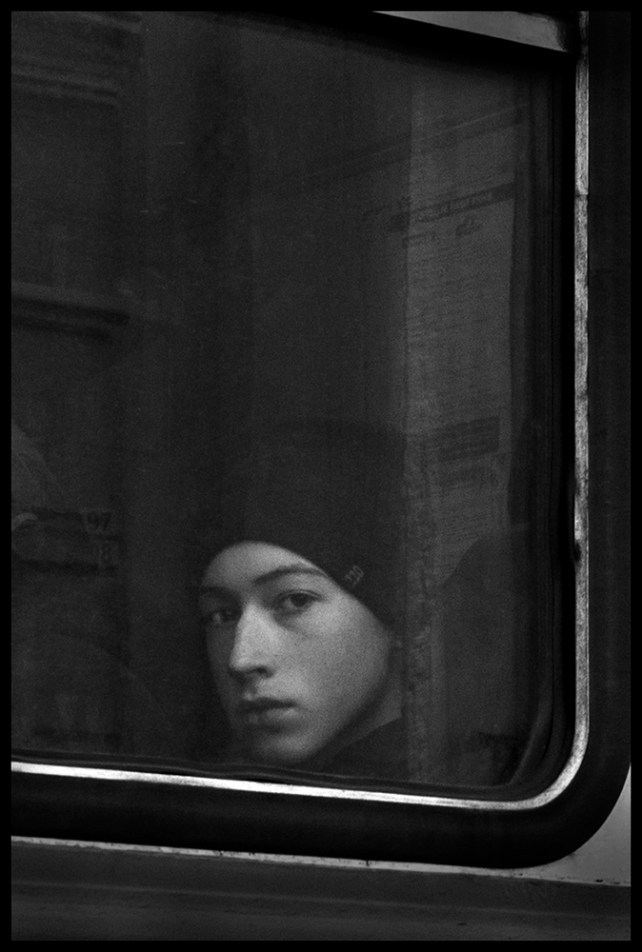

It was dark out as I descended from the train in Przemyśl. Several thousand refugees who had just arrived from Ukraine were boarding a train going in the direction of Prague. As I walked the platform, I looked into the eyes of dozens of refugees looking out the train window, waiting to depart for a new world—leaving behind everything they have previously known in life.

In this visual diary of the largest human exodus in Europe since World War II, I ask you to try to imagine that you have suddenly lost all—your home, your homeland, your neighbors, your family albums—and that you are leaving behind your husbands, brothers, and fathers, not knowing when or if you will ever see them again. This is what we are looking at.

Day 2, March 8

Oxanna, a newly arrived refugee from Irpin, Ukraine, turned 78 years old today. She sat on a bench on the railroad tracks in Przemyśl with no material possession from her nearly eight decades of life except for her clothes, her hat, her cane, and her coat.

I also met Lubov, standing along the tracks holding Marguerita, 10 months old. They have no idea where they will end up. Marguerita is a child of war. The magnitude of psychological scarring that this war is creating for millions of people is almost unimaginable.

I will likely enter Ukraine tomorrow, on my way to Lviv, where the train station is the focal point of departure for thousands of Ukrainians squeezing into rail cars to flee all they have ever known.

I’m a little lonely tonight as I write this. I cry. I’ve seen a lot, too much, but I have never been a refugee. People always conveniently think that the camera is a shield, but I have always tried to look straight into the eye of reality, and reality is hard.

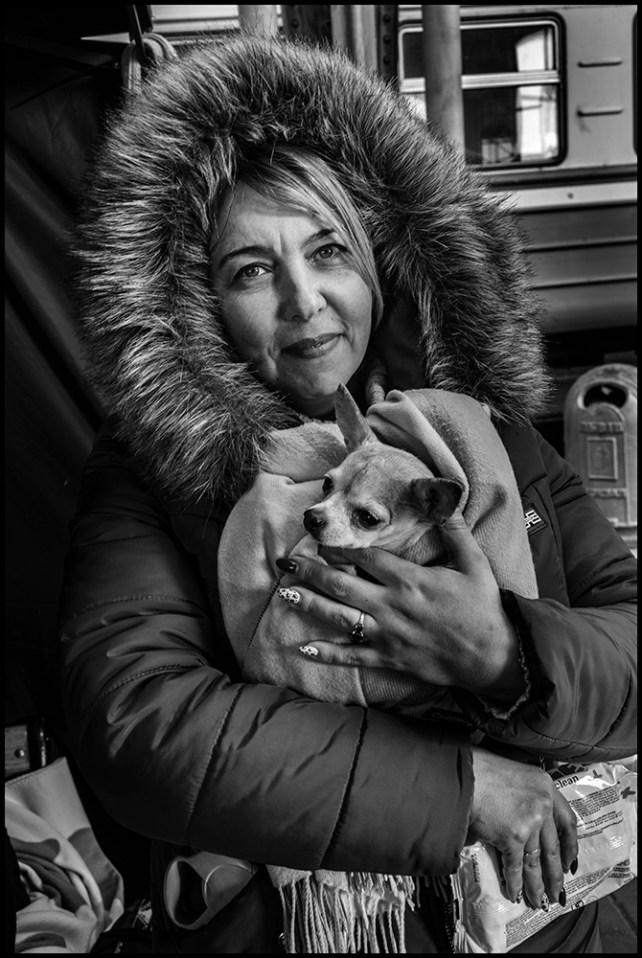

I have nothing to complain about in life, but realize at the age of 66 how much it is important and meaningful to me to witness and document love, which gives me hope and joy. Love, ironically, is what I see most in the movement and attitudes of refugees from war. People hold on to each other, hug each other, hold hands, and hold tight. Though imagine a refugee that has no one to hold on to—and there are certainly far too many.

I have been incredibly touched by the gestures of kindness I have seen by the Polish population that has been receiving hundreds of thousands of refugees from Ukraine. There are very, very many good people in this world.

Day 3, March 9

I am now inside Ukraine!

Today, I boarded a train in Przemyśl, where now many hundreds of thousands of Ukrainians have crossed through as they flee the brutal Russian invasion of their homeland.

In all my years, I have never been on a train quite like this: full of Ukrainian men going back to join the fight against the Russian military, women who had decided they could no longer stay away from their homes, and a handful of foreign journalists.

As the train passed through the border into Ukraine, it came to a stop, and many Ukrainian soldiers boarded the train, along with several Ukrainian border customs agents. Every passport was checked thoroughly, and one passenger was mysteriously removed from the train, not to board again.

As the customs check took place, another train arrived in the station where we were stopped, this one coming from Kyiv. It pulled up right next to ours. As I looked across the tracks, I peered into the windows of a cabin overflowing with passengers. Most of the people in the window of this train were mothers and children and many very young babies with their heads pressed against the window—a sight they will likely not remember in time, but a moment in their life they will never forget.

The young child seen here was on this train opposite mine. Despite their youth, they have been given a form of prison sentence by an invasion that has brutally imprisoned the freedom of millions of Ukrainians.

When the train arrived at the Lviv station in western Ukraine, every sight, every light, every face was different—tense, anxious, tired; thousands of people pressed upon each other in a narrow railway aisle, waiting to head out of the country.

A young man stood holding his wife as she cried. They looked each other in the eyes and whispered to each other. This couple was crying a goodbye that no person on this earth could ever be prepared for. I didn’t make a photograph of this moment, though I touched the shoulder of the young husband and told him I would think of him, and of them. He spoke to me and said, “At this moment, we don’t have the right words.”

As I finish tonight, I realize I too don’t have the right words. I have images that will stay with me forever—some sharp, and some very out of focus, and all with pain that no anesthesia will make lighter or more bearable.

Day 4, March 10

I woke up this morning in Lviv. I went immediately back to the train station and thousands of Ukrainian women and children were huddling in a small narrow hallway waiting and hoping to board a train for Poland.

When the train was ready to board, people hurried for any open door, hoping to get a seat. An elderly woman who could not walk was carried on by several men. I imagined my own mother who passed two years ago at 92. I would only believe that such suffering in life could happen if saw this with my own eyes. You will now see it too.

Vitali, 48, from Kharkiv, stood outside a box car staring into a window where his daughter Valeria, 8, and his wife, Lelena, were looking back at him. They stared at each other quietly but intensely for a long time. Suddenly, without notice, the train began to move, and before the family could be prepared they were separated. I found myself wanting to stop the train, to give Vitali time to say goodbye—but it was gone, and so was any certitude of a family’s future.

I am tired and drained, but I cannot complain. I think of some people having so much while others have so little, and it could of course make me upset, even angry, even sometimes outraged. But I see in the eyes of the thousands of Ukrainians, who now have so little of a material life, something that can never be bought: pride for their homeland, love for each other, and dignity.

I believe, in the end, sooner or later, it is this dignity, pride, and love that will offer a form of victory for Ukraine. These are things that simply cannot be beaten. Someone once said something that has stayed with me my whole life, “It’s not a good idea to fight me because in a fight, I may not win, but I will never lose.”

Day 5, March 11

I venture to say that no one reading this has ever taken a train ride like the one that thousands of Ukrainians, mostly women and children, made last night from Lviv to the border with Poland, and I hope to God that you never will!

Yesterday, I boarded a small train car at 4 p.m., and in there were hundreds of Ukrainians, all seats taken with children sitting on laps of mothers; every other inch was filled with people standing, sitting on the floor, and crowding into all the empty space available between the cars. I stood for most of the next 10 hours as our train went from Lviv to Przemyśl.

As the train pulled slowly out of Lviv’s station, tears began to flow in the eyes of most of the passengers, and people frantically made last minute phone calls to loved ones, with a sense this might be their last call. Eyes looked out the windows to see the last glimpses of a homeland that many knew they might not ever see again.

Marguerita, a woman from Bucha, stood next to me. Bucha, which is near Kyiv, has been badly bombed and shelled; she showed me a photograph of her destroyed home. Her husband had stayed behind, as all men up to the age of 60 must do at this time. I asked Marguerita where she was going and she lifted her hands up in the air and said, in English, “I don’t know, Europe?”

She then said to me, “Everybody on this train don’t have a plan.”

Most people on the train had only small bags. I asked myself, and continue to do so: How will they make it? Do they have credit cards, any money, clothes to wear?

An elderly man on the train, Antoniusz, stood with a cane, and he explained to the only other journalist in this train car—a wonderful man from Poland named Andrew—that he had neurological problems and could not keep one eye open all of the time.

Often during this ride of exodus, I looked into the eyes of elderly women. I could not bear to imagine the reality they were living. Many sat glassy eyed, staring at the ceiling of the train, or with a 100-yard stare to darkness. It was not lost upon me, and I am sure them, that many realized they would eventually die far from their home and a place they know.

As we arrived at the Polish border town, Antoniusz began to sing in Ukrainian with a beautiful, soulful, penetrating, and poetic voice. He was constantly teetering on one foot and after 10 hours he began to cry. He explained that he was so tired. He didn’t know how he would make it going forward.

The train cars offloaded one at a time. Our car was last, and we stood for two hours waiting. I wished everyone around me good luck in Ukrainian, but my words felt like they had no meaning. When the border guards finally opened our door, I descended and looked back to see Antoniusz being lifted into a wheelchair by the guards.

I was recounting parts of this journey this morning over breakfast to my brother, who is also a photographer, and another journalist staying in the same hotel in this Polish border town. As I spoke, I told them how guilty I felt that I could walk away from this moment and I knew no one else on this train could do the same. Without warning, I began to sob.

Shortly after, I received an email from Andrew, the other journalist who had been on the train. He said he had found out that Marguerita was heading to Dresden, Germany, and that he had no news of Antoniusz. I thought about how, on the train, when asked about the situation in the Ukraine, Antoniusz replied, “One thing is certain, if you are born, you will die.” When the train arrived in Poland, as I said goodbye to him, he looked at me and said, “Victory always.”

Day 7, March 13

Today, I drove along the border and I saw a message from someone that an American journalist, Brent Renaud, was killed in Ukraine. I did not know him, but my heart is shaken and my thoughts and prayers go out to his family and friends.

This is extremely dangerous work. The day before, I was riding again on the train car from Poland to Ukraine and sitting next to me were several younger photojournalists from the US, beginning their time in the country. As we rode on, little by little we got to know each other, and my heart was touched by each one because they reminded me of when I was much younger, and I could see in them a passion and hunger to share the stories of the world they would experience.

I don’t like, even hate, the expression “a picture is not worth dying for.” I feel it is very disrespectful to those who do fall in the line of work and implies they may have done something wrong. I prefer to think that some photographs and stories are worth living for—and that is why so many of my wonderful and courageous friends and colleagues, and those that preceded me, find it important to take conscious risks.

I said to these young photojournalists on the train, as I thought it could help them, “Don’t feel bad if you are scared—it is important to be scared. I am scared all of the time in war zones. Use it and follow your instincts.”

I will pray for all of my colleagues and friends in Ukraine and send love to them, and to all Ukrainians, and to many Russians who have the courage to stand up and protest this horrible invasion of a sovereign country. I will also pray for the safety of the younger photojournalists I met on the train.

I am on a plane back to Paris tonight. I feel a sense of guilt as I can leave to return to comfortable conditions, as so many Ukrainians cannot. I had planned to leave today, and it is time for me to go, for now.

Day 8, March 14

I arrived home in Paris after midnight. My compass is turned upside down. I have no reason to complain about anything, but my life is changed from all that I have seen.

I’m thinking about yesterday, when I visited a border checkpoint at Medyka, Poland, and a rescue center nearby. I witnessed people taking their first step out of their homeland, walking past Polish border guards, to a new reality. I met Valentina, from Kyiv, sitting on a cot in the middle of the large warehouse, near the border crossing, that is serving as the rescue center. The irony was not lost upon me that this huge warehouse, usually a place that stored goods, has become a warehouse of human beings that have lost everything, except their bodies and hearts. She explained to me that she had been forced to flee as fighting was taking place very near where she lived.

The life of a refugee consists of many phases: There is the dramatic first phase of fleeing or being forced to flee one’s homeland, leaving all behind. At some point a new phase begins: establishing a new life, and in many ways a new identity in a new place and country, with new language, culture, and history.

War, in this case a brutally inhumane invasion, forces not only physical devastation, but psychological destruction. In this warehouse refugee camp sat thousands of Ukrainians, each with their own story, history, past, and now present and future, that will be different one from another, but all involving a profound degree of suffering.

We have spent two years emerging for what I thought was a form of World War III with a virus. Now, the world is at the brink of a true world war. Over 2.5 million people like Valentina are now sitting in disbelief and living with trauma that will now last for the rest of their lives.

Day 9, March 15

Even after all of these years of covering war, man-made and natural disasters, revolution and upheavals, I was not ready for this transition to what for most people is a normal day in their lives. But what really is normal? It all depends on one’s perspective, luck, good fortune, and unfortunately too often, privilege for some and lack of opportunity and oppression for others. When I first began photography, I was incredibly inspired by photographers like Lewis Hine, Jacob Riis, Dorothea Lange, W. Eugene Smith, and many others who saw photography not only as a form of expression, but an engine of change.

The only way I know how to protest is to show the reality of life with photographs. And, as long as I am alive, I will let no one steal that right away from me.