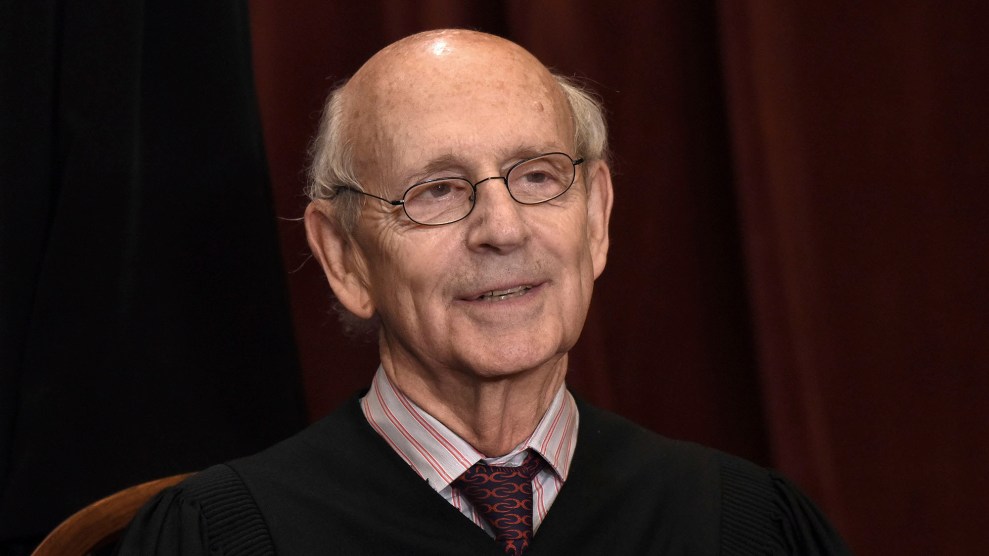

Associate Justice Stephen Breyer sits during a group photo at the Supreme Court in Washington, Friday, April 23, 2021. Erin Schaff/New York Times via AP, Pool

After nearly three decades on the US Supreme Court, Justice Stephen Breyer, 83, is stepping down, paving the way for President Joe Biden to make his first nomination to the high court, NBC News reports.

Breyer has been under heavy pressure since the November 2020 election to retire so that a Democratic president would have ample time to replace him, lest he end up like the late Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg. Ginsburg’s refusal to retire during the Obama administration allowed President Donald Trump to replace her in 2020 with Amy Coney Barrett, a 49-year-old arch conservative whose ascension to the court threatens the future of abortion rights and other laws geared toward gender equality.

During his nearly three decades on the court, Breyer has proven to be a pragmatic and solid moderate, though as the court has tilted rightward in the past decade, he has become known more for his position in the court’s liberal voting bloc. A reliable defender of abortion rights, he’s also known for showing far more respect for the work of legislative bodies than many of his conservative colleagues, a trait seen as the result of his experience helping the sausage get made in Congress.

Liberals had been outspoken in their insistence that Breyer retire early in Biden’s tenure while Democrats have 50 votes in the Senate. They are hoping to avoid a repeat of 2016, when Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell blocked President Obama’s effort to replace Justice Antonin Scalia with current Attorney General Merrick Garland, when Scalia died at age 79. A Business Insider columnist wrote a piece titled “Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer Should Just Retire Already,” noting that the justice is “really old.” Erwin Chemerinsky, dean of the University of California Berkley law school, who tried to get both Ginsburg and Breyer to retire in 2014, took to the pages of the Washington Post in early May 2021 to make the case again, this time arguing that if control of the Senate should shift in 2022, the existing window for Biden to replace Breyer with someone who shares his values is small and shrinking. “Though he can’t predict the future,” he wrote, “Breyer’s best chance at protecting his legacy and impact on the law is to resign now, clearing the way for a younger justice who shares his judicial outlook.”

Breyer resisted the mounting pressure, giving a speech at Harvard law school in April 2021 where he subtly shot back at the retirement pressure and decried partisanship in the judiciary. “My experience of more than 30 years as a judge has shown me that, once men and women take the judicial oath, they take the oath to heart,” he said. “They are loyal to the rule of law, not to the political party that helped to secure their appointment.” The justice has continued to argue publicly that the Supreme Court is not a partisan institution, despite mounting evidence to the contrary, and he pushed back on the calls for his retirement, assuring Fox News’ Chris Wallace in September that “I don’t intend to die on the bench.” But today’s news suggests he apparently got the message.

With Breyer’s departure, the high court will lose its last member with any experience working in the legislative branch, which is significant for a high court that since the retirement of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor, a former Arizona state legislator, has been dominated by people whose primary experience in government has been in the executive branch. In 1974, after serving as a Watergate prosecutor, Breyer became special counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee, where he helped the late Sen. Ted Kennedy (D-Mass.) write and pass the Airline Deregulation Act, drawing on his expertise in anti-trust law honed previously during his two years working at the Department of Justice anti-trust division. In 1979, Breyer would become chief counsel to the Judiciary Committee, which Kennedy chaired.

Kennedy helped launch Breyer’s judicial career, first by helping him land a seat in 1980 on the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals in Boston, where he became chief judge of the circuit in 1990, and then by championing his nomination to the Supreme Court. Breyer first came under consideration in 1993 to replace retiring Justice Byron White. A few days before he was scheduled to meet with President Bill Clinton to discuss the position, he was hit by a car while he was riding his bike in Boston’s Harvard Square. He suffered broken ribs and a punctured lung and had to do some of his preliminary interviews with White House staffers from his hospital bed.

Breyer, who couldn’t fly because of his punctured lung, left the hospital to take the train to DC for lunch with Clinton at the White House. But he was still in pain from the accident and the meeting reportedly did not go well. Clinton ultimately tapped Ginsburg for the seat, nominating Breyer the following year to replace retiring Justice Harry Blackmun. His nomination was uncontroversial, and most of the opposition came from Democrats, who thought he was a bloodless technocrat and insufficiently committed to civil rights. The Senate confirmed him 87 to 9.

While Breyer secured his dream of getting on the high court, bike accidents would continue to plague him. In 2011, he broke his collarbone after taking a spill while riding his bike near his house in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and in 2013, he fell while biking on the National Mall and required surgery for a fractured shoulder. The bike mishaps seemed to have reinforced Breyer’s avuncular image as something of an absent-minded professor. He started teaching law at Harvard in 1967, a few years after his graduation from there and has continued to lecture at the school ever since.

Breyer’s tenure on the Supreme Court was not marked by a string of notable opinions as was Ginsburg’s, nor by the sort of witty and scathing dissents the late Antonin Scalia was famous for. He hasn’t been the leading voice on many hot-button or contentious cases, in part because Breyer’s first two decades on the court were spent largely in the shadow of the late Justice John Paul Stevens. As the longest-serving justice on the court at the time, Stevens was able to assign the best cases to himself, rather than other liberals on the court. He retired in 2010 at the age of 90 and was replaced by Justice Elena Kagan.

But since Stevens’ retirement, Breyer has written several important decisions affecting abortion rights, including the landmark 2016 majority opinion in Whole Woman’s Health v. Hellerstedt. This decision struck down a Texas law that imposed so many restrictions on the operation of abortion clinics and doctors practicing in them—like requiring abortion doctors to have admitting privileges at a hospital within 30 miles of a clinic—that the number of clinics in the state fell by about half. Texas had argued that the restrictions were necessary to protect women’s health, but Breyer’s opinion found that the Texas law created an undue burden on women seeking to exercise their rights to obtain an abortion, making it unconstitutional. During oral arguments in the case, Breyer asked the lawyer from Texas whether he could point to a single example of where the new law had improved medical care for even one woman. He could not.

In 2015, Breyer penned an impassioned dissent in Glossip v. Gross in which he called for the court to reconsider the constitutionality of the death penalty, which the court has not done since 1979. In an opinion packed with tables and charts of statistics on the death penalty in the US, Breyer suggested that the death penalty has become not just cruel, but unusual, demonstrated by the fact that 80 percent of states no longer use it. He pointed to convincing evidence that innocent people have been executed and the frequency of wrongful convictions to make his case that “the death penalty, in and of itself, now likely constitutes a legally prohibited ‘cruel and unusual punishmen[t].’” He wrote that the sporadically applied death penalty in the US “is the antithesis of the rule of law.” Since then, he has dissented in several other death penalty cases to press for the abolition of the practice.

The mild-mannered Breyer may not have a long string of fiery dissents or landmark opinions behind him, but he has distinguished himself during oral arguments at the court with his famously zany and wandering hypothetical questions, a habit he picked up from his years of trying to entertain students in his anti-trust classes at Harvard. His questions are often meandering but they’re subtly designed to focus the discussion on the legal issues in front of the court, not necessarily the specific facts of one individual case.

Consider Breyer’s raccoon ruminations during a case concerning a patent dispute over a gas pedal:

“Now to me, I grant you I’m not an expert, but it looks at about the same level as I have a sensor on my garage door at the lower hinge for when the car is coming in and out, and the raccoons are eating it. So I think of the brainstorm of putting it on the upper hinge, OK? Now I just think that how could I get a patent for that?”

Other examples were less straightforward, notably his questions in a medical marijuana case where he questioned the government’s interest in marijuana growers. “You know, he grows heroin, cocaine, tomatoes that are going to have genomes in them that could, at some point, lead to tomato children that will eventually affect Boston,” Breyer said cryptically. Bloomberg even made a campy video of Breyer’s greatest hits from clips of oral argument audio, which you can watch here:

Breyer’s retirement will give President Biden his first opportunity to make an appointment to the Supreme Court, and he has promised to make it a historic one. During the presidential campaign he indicated repeatedly that he would put a Black woman on the bench, so it’s not surprising that there are several Black women viewed as contenders to replace Breyer. Top among them is a former Breyer clerk, Ketanji Brown Jackson, currently a judge on the US District Court for the District of Columbia who was appointed by President Barack Obama in 2013. A double-Harvard graduate, Jackson is young—at 51, she is just a few months older than the court’s youngest justice, Amy Coney Barrett—and previously worked as a federal public defender, experience sorely lacking on a high court dominated by former prosecutors. In a move seen as positioning her to eventually advance to the Supreme Court, Biden nominated Jackson to replace Merrick Garland on the DC Circuit Court of Appeals after tapping Garland to serve as attorney general. She was confirmed in June in a 52–46 vote.

CNN reports that Breyer will make his official announcement on Thursday at the White House with President Biden.