Receiving a presidential pardon for subverting the government is not a novelty in the United States, though the Trump era made it almost a stamp of approval for criminal behavior. In an interview with Rolling Stone, an organizer of the “Stop the Steal” movement claimed that, before the Capitol breach, Rep. Paul Gosar (R-Az.) promised a “full pardon” for their “hard work” and said Trump was also on board.

“I would have done it either way with or without the pardon,” the organizer, who was granted anonymity by Rolling Stone, added. Gosar joined 197 other House Republicans who voted not to impeach Donald Trump for “incitement of insurrection,” absolving Trump of Section 3 of the 14th Amendment, which forbids any person who has “engaged in insurrection or rebellion against” the United States from “hold[ing] any office…under the United States,” itself a pardon of sorts.

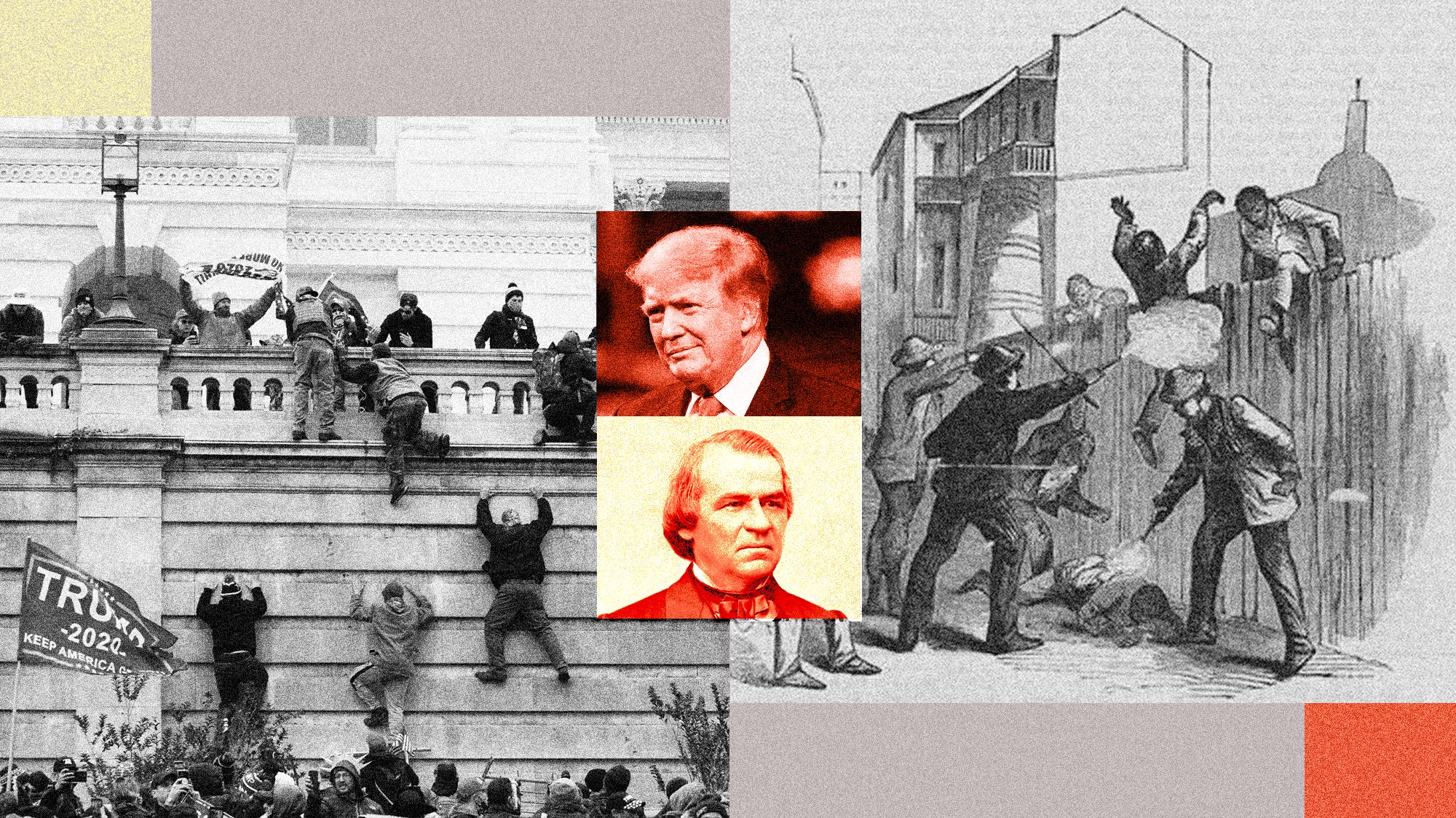

Of course, now that Trump is out of office, the January 6 rioters aren’t going to get pardoned anytime soon. But the insurrectionists and their leaders have an awful lot in common with another group of white people who tried to destroy the country: Confederate soldiers. And the era of Reconstruction offers lessons for what happens when the government allows traitors posing as patriotic legislators to remain in its midst.

On December 8, 1863, while the war was still raging, Abraham Lincoln issued his Proclamation of Amnesty and Reconstruction, which, in a bid to popularize emancipation, gave a full pardon to all Confederates who took an oath of allegiance to the United States, excepting the highest-ranking officials. Once 10 percent of those who voted in the 1860 election took the oath of allegiance, a state could be readmitted to the union. Private property of Southerners would be restored, so long as emancipation was accepted. The goals of Lincoln’s proclamation were to “suppress the insurrection” and provide a pathway for Confederate states to join the union; in other words, to allow the South to turn over a new leaf and help the country move forward.

Radical Republicans feared Lincoln’s 10 percent plan was too lenient. They were proved right when, after Lincoln’s assassination, President Andrew Johnson—who not a year earlier gave a speech saying, “I am for a white man’s government, and in favor of free white qualified voters controlling this country, without regard to negroes”—began undermining Reconstruction. He started by pardoning high-ranking Confederates. Among them was Harry T. Hayes, a former Confederate general who led the rebels at Gettysburg. Following Hayes’ pardon, he became sheriff of New Orleans and in 1866 deputized fellow Confederates to disrupt a Louisiana constitutional convention. When a delegation of 130 Black citizens marched to the convention to extend voting rights to free Black people, remove Black Codes, and disenfranchise ex-Confederates, Hayes and his deputies fired upon the group, killing at least 40 free Black people in what is known as the New Orleans massacre.

In a speech, Johnson blamed the massacre on the “Radical Congress” pushing for a “new government” that intended “to enfranchise one portion of the population, called the colored population, who had just been emancipated, and at the same time disenfranchise white men.”

Trump, who opposed redesignating military bases named after Confederate generals, echoed Johnson days after the insurrection, blaming “antifa people.” He repeated the refrains he’d been pounding on for months, falsely accusing predominantly Black counties of election fraud. “All of us here today do not want to see our election victory stolen by emboldened radical-left Democrats.” Trump’s “radical-left Democrats” are Johnson’s “Radical Congress,” a coalition of progressives who attempted to thwart their president’s anti-Black agenda. Like Johnson, Trump views Black suffrage as antithetical to his political existence. “If you don’t fight like hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore.”

Trump’s lies about the insurrection were a remastering of the South’s “lost cause,” a Confederate myth that the Civil War was not a battle for slavery but for “states’ rights” against Northern aggressors, and that white enslavers were benevolent owners of Black human beings. The lost cause presented Confederates with an attractive concession: The South lost the war not because their position was morally repugnant but because the North had superior resources.

Jefferson Davis, president of the Confederate States of America, touted the “lost cause” in his autobiography, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government. “I confidently refer for the establishment of the fact that whatever of bloodshed, of devastation, or shock to republican government has resulted from the war, is to be charged to the Northern States.” Davis was pardoned on December 25, 1868, when Johnson extended amnesty to each person who’d participated in the rebellion—which jettisoned Davis’ trial for treason and contravened Republicans’ attempts to punish Confederate soldiers—ultimately expunging every Confederate of crimes against the United States. (Although Davis was pardoned by Johnson, he was not allowed to vote or hold office. Davis was posthumously awarded “full rights of citizenship” in 1978 by Jimmy Carter.)

Trump reappraised the violence, treachery, and death his supporters caused on January 6 as honorable protest of “innocent people” whose rights were plundered. In Trump’s contemporary fiction, he did not lose the election—his presidency was overthrown by Democratic marauders, and he lacked the political resources to surmount their coup. In the year since, the eulogy for the lost cause of January 6 has only grown stronger. According to a Reuters/Ipsos poll conducted in early January, 55 percent of Republicans believe the Capitol breach was the work of leftists to demonize Trump supporters.

Participants in the Capitol breach have their own mythology. Robert Reeder, a former FedEx driver from Maryland, portrayed himself as merely an “accidental tourist” who was at the Capitol to “document” the events. Reeder channeled the “lost cause” when he blamed law enforcement for the storming of the Capitol. “It’s almost like they wanted us to come in there and they closed the doors and then they have their sound bite for the news, you know…that was kind of a plan to allow people in and then drop them and then, you know, demonize the Trump people.” The sentencing memorandum filed by Reeder’s attorney depicted him as a reluctant insurrectionist, a virtuous documentarian and defender of the Capitol.

This directly borrows from the myth of the “reluctant Confederates,” those who supported the Union during the secession but acquiesced to the Confederate cause when war broke out. Such essentially was the claim about Lee himself. “I had to meet the question whether I should take part against my native State,” Lee wrote in an 1861 letter to his sister. “With all my devotion to the Union and the feeling of loyalty and duty of an American citizen, I have not been able to make up my mind to raise my hand against my relative, my children, my home. I have therefore resigned my commission in the Army, and save in defense of my native State, with the sincere hope that my poor services may never be needed, I hope I may never be called on to draw my sword. I know you will blame me; but you must think as kindly of me as you can, and believe that I have endeavored to do what I thought right.” Although Lee signed his Amnesty Oath in 1865, he was posthumously pardoned and received full citizenship rights in 1975 by President Gerald Ford, who remarked, “General Lee’s character has been an example to succeeding generations, making the restoration of his citizenship an event in which every American can take pride.” Reeder and other insurrectionists share a false narrative with Lee that claims they are noble, law-abiding citizens who were following the crowd.

Federal prosecutors repudiated Reeder’s “self-serving rewrite of history that sought to portray himself as a hapless tourist to absolve himself of any wrongdoing.” They asked for harsh sentencing. “A lesser sentence would suggest to the public, in general, and other rioters, specifically, that criminal acts in support of a political cause are a crime which will go without serious punishment. In this way, a lesser sentence could encourage further and more serious—if not deadly—abuses.”

Reeder was hardly alone. Jenna Ryan, a Texas real estate agent who pleaded guilty to illegally demonstrating in the Capitol building, told CBS 11, “I just want people to know I’m a normal person. That I listen to my president who told me to go to the Capitol. That I was displaying my patriotism while I was there and I was just protesting and I wasn’t trying to do anything violent and I didn’t realize there was actually violence. I am not a villain that a lot of people would make me out to be, or people think I am, because I was a Trump supporter at the Capitol. I think we all deserve a pardon. I’m facing a prison sentence. I think I do not deserve that and from what I understand, every person is going to be arrested that was there, so I think everyone deserves a pardon, so I would ask the President of the United States to give me a pardon.”

The attempt by Trump and the January 6 insurrectionists to justify their actions was prophesied in a November 1868 report by US Army General George Henry Thomas, a Virginian who had fought for the Union only to see former Confederates rewrite their rebellion in a positive light:

“The greatest efforts made by the defeated insurgents since the close of the war have been to promulgate the idea that the cause of liberty, justice, humanity, equality…suffered violence and wrong when the effort for southern independence failed…whereby the crime of treason might be covered with a counterfeit varnish of patriotism, so that the precipitators of the rebellion might go down in history hand in hand with the defenders of the government, thus wiping out with their own hands their own stains; a species of self-forgiveness amazing in its effrontery.”

That counterfeit varnish had a ripple effect: The Confederate pardons helped spur the collapse of Reconstruction and continuation of the deadly abuses against Black Americans. By the end of 1865, four Confederate generals, five Confederate colonels, six members of the Confederate Cabinet, and 58 members of the Confederate Congress ran for seats in the congress they tried to destroy. Just six months after the Civil War, former Confederate Army General Benjamin Humphreys was elected governor of Mississippi. Humphreys received a pardon from Johnson after he won. In Humphreys’ inaugural address, he said, “The State of Mississippi has already, under pressure of the result of the war, by her own solemn act, abolished slavery. It would be hypocritical and unprofitable to attempt to persuade the world that she had done so willingly…And it should never be forgotten—to maintain the fact that ours is and shall ever be a government of white men.”

Southern states conceded that while slavery was abolished, their desire for an anti-Black republic could be preserved through legislation. The Mississippi legislature quickly passed An Act to Regulate the Relation of Master and Apprentice as It Relates to Freedman, Negroes, and Mulattoes, one of many “Black Codes” designed to keep Black people essentially enslaved. Section 1 mandated civil officers in the state of Mississippi to report all “freedmen, free negroes, and mulattoes, under the age of eighteen…who are orphans, or whose parent or parent have not the means, or who refuse to provide and support said minors,” to a court official to be “apprenticed” to “some competent and suitable person.” Such laws—representing the attitudes of the Confederate regime and its ideology of Black subjugation—were the inevitable result of the pardons.

If democracy cannot be subverted violently, it can be depleted legislatively. It’s the axiom of a bygone era but an immortal American dynamic.

Like Confederate sympathizers who voted ex-rebels into Congress, Republicans in multiple states are seeking to elect Trump supporters who will orchestrate a further erosion of the rule of law. In 2020, 18 of the 23 senate candidates Trump endorsed won their elections. Of the 149 House candidates Trump endorsed, 116 won their general elections. Eighty-six Trump-endorsed congressional candidates are running in 2022. An NPR analysis of 2022 secretary of state races across the country found at least 15 Republican candidates questioned President Biden’s 2020 victory. Should they win, it will be a reconstruction of 1865, when traitors and ex-Confederates were elected to Congress to subvert democracy. Back then, Radical Republicans introduced legislation to keep ex-Confederates from entering Congress. Last year, Rep. Cori Bush (D-Mo.) introduced a bill to expel members of Congress who sought to overturn the election. That bill will go nowhere.

Trump and the Confederacy are engaged in the same project but employ different means. Just as members of the Confederacy enacted anti-Black legislation once elected to Congress, modern-day Republicans have passed voter-restriction laws after they failed to overturn the 2020 election. Between January 1 and December 7, at least 19 states passed 34 restrictive laws. Georgia passed SB 202, a law that criminalizes passing out water to voters waiting in line, and grants the state’s board of elections the power to remove election officials and seize control of specific jurisdictions. One aspect of the bill is targeted at “souls to the polls,” voter turnout drives used by Black churches on Sundays before an election. Jody Hice, a Republican endorsed by Trump and member of the House Freedom Caucus, is running to become Georgia’s chief elections official in 2022. She voted to overturn the results of the 2020 election and, in a social media post, called January 6 “our 1776 moment.” A moment when Black people were slaves and could not vote, an epoch the Confederacy tried to conserve and Trumpians attempt to resurrect.

Yes, some participants in the Capitol breach are being punished. But the political power of their anti-Democracy views persists. Lessons from Confederate pardons loom large. The failure to eradicate the Confederate cause and punish its overseers has cast a shadow on the future of a country that has yet to emancipate itself from its history.

Top image: Mother Jones illustration; Jose Luis Magana/AP; Brian Cahn/Zuma; Library of Congress; Engraving of sketch by Theodore R. Davis/Wikipedia