In early 2020, just as the COVID-19 pandemic was starting to unfold, infectious disease researchers Matt Memoli and Luca Giurgea were already thinking about how the crisis might end. The two, both at the Laboratory of Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health, recalled what happened following a coronavirus epidemic 17 years earlier, and they were concerned about a repeat.

They remembered that, as SARS (caused by a kind of coronavirus) jumped to humans, possibly from bats, and began spreading across the globe in late 2002—eventually infecting more than 8,000 people and killing 774—researchers started working on some of the first commercial human coronavirus vaccines. But within months, health authorities contained the outbreak. And as the threat of SARS subsided, so did their funding. Projects were put on hold or abandoned.

Too bad, because they really could have come in handy.

Now, after three coronavirus-sparked health crises in the last 20 years—SARS, MERS, and COVID-19—researchers are working to develop so-called universal coronavirus vaccines for the next outbreak. While COVID-19 vaccines are an incredible feat of science—they were created faster than any vaccine in history—researchers say it wasn’t fast enough. Kevin Saunders, the director of research at the Duke Human Vaccine Institute, points out that hundreds of thousands of Americans died from COVID-19 infections while vaccines were being developed and approved. If we have a universal coronavirus vaccine ready to go in the future, even if it isn’t perfect, he says, it could cut down on hospitalizations and deaths, and buy researchers time to hone a virus-specific vaccine.

Indeed, many coronavirus vaccines are already in development, some with promising results in animal models. Many of these vaccines, including the one Saunders and his colleagues are working on, present our bodies with a specific segment of the spike protein that’s shared among many coronaviruses, an “Achilles heel,” as he put it. In Saunders’ vaccine, copies of this critical piece of the spike protein are fused to a protein nanoparticle like darts in a soccer ball. It’s a design that’s been used to fight viruses like influenza, RSV, and HIV. The first broadly protective coronavirus vaccine to be tested in humans, developed by researchers at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, uses a similar technology. Their vaccine, like others in the pipeline, focuses on one branch of the coronavirus family: SARS-like viruses. But the “ultimate goal,” according to Kayvon Modjarrad, an infectious disease researcher at Walter Reed who co-invented the vaccine, is a shot that covers all coronaviruses.

Other vaccines rely on mRNA, just like the COVID-19 vaccines developed by Pfizer and Moderna, with one significant change: Instead of instructing our immune systems to make a SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, these vaccine prompts our bodies to produce a “chimeric” spike protein—a blend of several coronavirus parts. In animal trials, explains David Martinez, a viral immunologist at UNC-Chapel Hill who is testing an mRNA vaccine, mice that received a dose were protected against SARS-CoV-2 (and some of its variants!)—as well as several related viruses, including the 2003 SARS virus, and two bat coronaviruses that haven’t spilled into humans. Another vaccine design, like the one Memoli and Giurgea are working on, is composed of a cocktail of whole, dead coronaviruses.

Coronaviruses, of course, aren’t the only group of viruses that pose a threat to humans. Influenza is also high on the list for global crisis potential. With major flu outbreaks having occurred in 1918, 1957, 1968, and 2009, the World Health Organization warns, “The world will face another influenza pandemic—the only thing we don’t know is when it will hit and how severe it will be.” This year, Memoli and Giurgea, who pivoted from influenza to COVID when the pandemic started, expect to conduct Phase I trials for their universal flu vaccine, which so far has been “very successful against every flu virus [they] throw at it” in animals, Memoli says. Their vaccine, they hope, will replace seasonal flu shots and instead require at most one or two boosters in a lifetime. Other researchers are hoping to build an arsenal of vaccines that offer broad protection against 20 virus families, including those that cause Zika, Nipah, and Chikungunya.

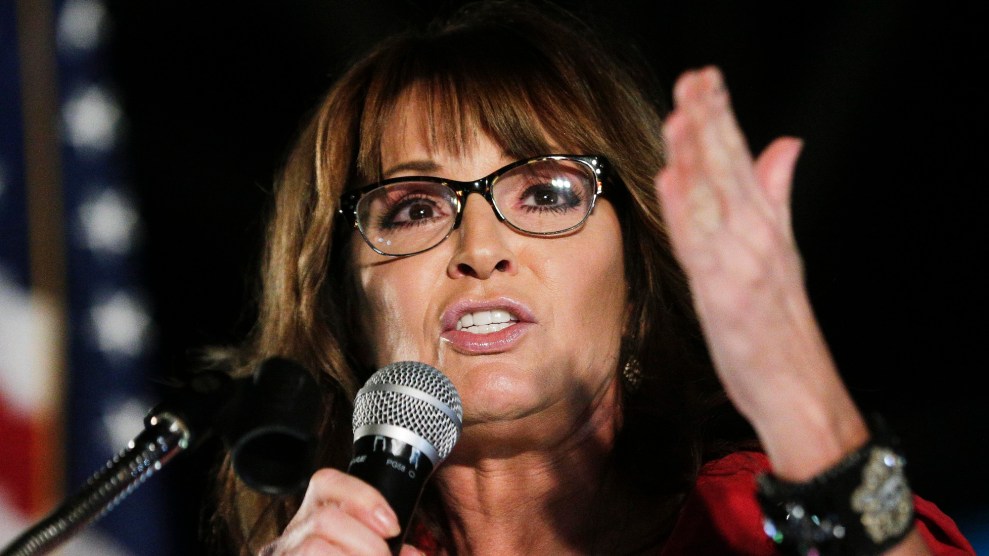

To get there, researchers will need political buy-in, both in spirit and in cash. The price tag for developing a universal vaccine of any sort is likely “$100 million to $200 million over several years,” according to scientists at Scripps Research. Similarly, Dr. Anthony Fauci told the New York Times in July that building a stockpile of universal vaccines could cost “a few billion dollars” a year over several years (and that’s not including the cost of promoting the vaccines and convincing the public to actually take them). That funding exists at the NIH and philanthropies such as the Gates Foundation, Memoli says. But getting that cash is another question. “They give money to the same researchers with the same old, failed ideas,” he tells me—meaning funders often want to rely on vaccine designs that already exist. Instead, he says, we should “actually think about how the viruses cause disease first and then develop a vaccine to target it rather than trying to force our platforms to work for a disease.”

Sure, making new vaccines won’t come cheap, but it’s a relatively small price to pay when the alternative is a pandemic: By one estimate, this pandemic will cost the world as much as $16 trillion in economic damage over the next decade. That’s about “500 times more than would be required for preventing the next pandemic,” Human Vaccines Project CEO Wayne Koff co-wrote in a February 2021 Science editorial. “We can either invest now or pay substantially more later.”

The unfortunate reality is, experts say, “later” will come. The animal world is teeming with pathogens: As many as 1.7 million undiscovered viruses live in mammals and birds; up to an estimated 827,000 can infect humans, according to a UN-backed consortium of researchers. As we continue to encroach on animals’ habitats—through deforestation, wildlife trafficking, and urban expansion—the risk of another outbreak only grows.

“The viruses have been around for billions of years, we’ve been around for 200,000, maybe,” Modjarrad says. “If this is a foot race, and if we start at the same starting line as the viruses, we’re always going to lose.”