Reps. Ilhan Omar (Minn.) and Cori Bush (Mo.), pictured here opposing the construction of an oil pipeline in Minnesota, are two Democrats who have met with the Taiwanese representative to the United States.Stephen Maturen/Getty

When Taiwanese President Tsai Ing-wen was inaugurated for a second term last May, then–Secretary of State Mike Pompeo and other senior officials sent high-level messages to congratulate her. It was the first time a US secretary of state had done so, and the news landed with a thud in Beijing, which has considered independent Taiwan a “breakaway province” for more than 70 years and regularly declares its intention to annex the island. In a statement, China’s defense ministry said that Pompeo had “seriously endangered relations between the two countries and two militaries and seriously damaged peace and stability in the Taiwan Strait.”

For decades, the United States had preferred to help Taiwan “quietly” so as to not anger Beijing, said Lev Nachman, a fellow at the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies at Harvard University. Taiwan policy was also mostly bipartisan—both parties agreed to the One China policy, a purposefully vague formulation that acknowledges China’s claim to Taiwan, but without taking a position on it. All that changed during Donald Trump’s presidency, Nachman told me, when “Taiwan policy became very loud.” And in the din, Democrats have had a hard time making themselves heard, let alone understood.

As Republicans—and some moderate Democrats—have adopted a more openly hostile stance toward Beijing over the past several years, progressives, in particular, have been left struggling to outline a position that both supports the Taiwanese people and also helps avoid drawing the United States into a devastating war with China. “On the messaging war,” one progressive congressional aide told me, “we’re losing.”

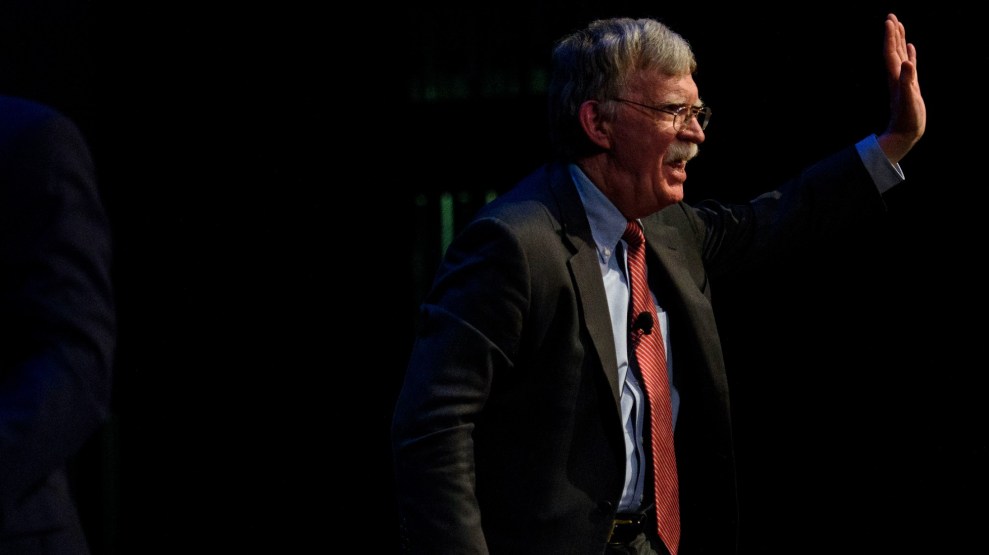

At the same time, Taiwan has moved cautiously to cultivate more progressive support in the first year of the Biden administration. A few weeks ago, for example, Hsiao Bi-khim, the Taiwanese representative to the United States—essentially a pseudo-ambassador, since Taiwan does not have formal diplomatic relations with the United States—had dinner with Reps. Cori Bush (D-Mo.) and Ilhan Omar (D-Minn.), the aide told me.

Taiwan’s entreaty to some of the party’s leading leftists was a striking change from its policy under the Trump administration, but also served as a reminder of how Democrats are still, slowly and not always surely, figuring out how to talk about Taiwan—and, by extension, China. Even as Republicans and Democrats remain broadly aligned on the substance—Biden has extended Trump’s trade war while the Senate passed a bipartisan China bill—progressives remain uneasy with the hawkish tone of the debate and its potential impact on Asian Americans.

That came into sharper relief last month, when Democratic Rep. Elaine Luria (Va.), vice chair of the House Armed Services Committee, wrote a Washington Post op-ed laying out a much more combative view of Taiwan policy. She called on Congress to “untie Biden’s hands on Taiwan” and mentioned a bill introduced earlier this year by Sen. Rick Scott (R-Fla.), which would give Biden authority to use the military to defend Taiwan. Luria did not expressly endorse the bill, but called it “a good starting point.”

Not many Democrats—and certainly no progressives—will be inclined to agree with her. “You’ll find very few Democrats who think we should give preemptive war authorizations in any way whatsoever,” said Stephen Miles, executive director of progressive advocacy group Win Without War.

But however far-fetched Luria’s position may seem to her fellow Democrats, her concern about China’s rising hostility is hardly out of step with the foreign policy establishment, which has noted with horror as China continues to fly fighter jets at a menacing distance from Taiwan. Nearly every day brings another throat-clearing missive about China’s potential for violence—and the need for the United States to respond.

“Get ready for the ‘terrible 2020s’: a period in which China has strong incentives to grab ‘lost’ land and break up coalitions seeking to check its advance,” wrote American Enterprise Institute fellows Michael Beckley and Hal Brands last week in one such essay for The Atlantic. Dealing with China, they conclude, “means preparing for a war that could well start in 2025 rather than in 2035.”

Miles fears the Democrats will revive their mistakes of the early 2000s, when instead of opposing the George W. Bush’s administration’s Middle East wars, they rubber-stamped them. “It’s like the worst of the War on Terror and the worst of the Cold War combined,” he said.

For progressive Democrats already searching for a way to talk about China, Taiwan presents a unique challenge. For one thing, it requires military support of the kind that progressives loathe to support. “This is, to be honest, a difficult or tense thing for a lot of peace and foreign policy groups, given our opposition to US militarism,” said Tobita Chow, director of Justice is Global, a project of progressive advocacy group People’s Action.

A few months ago, Chow and other progressive foreign policy thinkers, including some in government, began regular conference calls to strategize about China policy. They have even assigned reading, including Biden appointee Rush Doshi’s book, The Long Game: China’s Grand Strategy to Displace American Order, which outlets like the National Interest have described as a window into Biden’s thinking about China. “We’re trying to understand the perspective and the arguments,” Chow said, so as to get “better at critiquing it.”

One strategy the progressive congressional aide mentioned was to highlight the non-military challenges to Taiwan, including cyberattacks and pro-Beijing disinformation. The progressive position, the aide said, should be: “We’re the only ones serious about defending Taiwan right now because we’re not trying to provoke China.”

In other words, the opposite of Trump’s foreign policy. He began his tenure by controversially receiving a congratulatory call from Tsai and ended it by lifting longtime State Department restrictions on contacts between US and Taiwanese officials. Biden’s strategy has been to soften the Trump administration’s tone while keeping many of its policies. He has also kept the spotlight on Taiwan through a series of gaffes—appearing to call Taiwan a NATO ally, stating plainly that the United States would defend Taiwan from a Chinese attack, and erroneously referring to a “Taiwan agreement”—but his administration insists that its Taiwan policy has not changed.

For Harvard’s Nachman, treating Taiwan as purely military issue ignores the ways multilateral diplomacy can expand Taiwan’s pool of friends on the international stage, which itself can help ward off China. “There are viable ways that we can create deterrents away from military conflict, rather than ramping up our own military,” Nachman said.

But for progressives to meaningfully assert that message, they have to start speaking about Taiwan more publicly—or at least start interacting more with Taiwanese representatives. “I sometimes think,” the progressive aide told me, “I’m the only one who calls them.”