In May 2019, the University of Texas dermatologist Adewole Adamson published an opinion piece in the Washington Post debunking recommendations that Black people should wear sunscreen to prevent skin cancer. “Many dermatology and skin-cancer-focused organizations (a few of which I’m a member) promote the public health message of sunscreen use to reduce melanoma risk among black patients,” he wrote. “But this message is not supported by evidence. There exists no study that demonstrates sunscreen reduces skin cancer risk in black people. Period.”

Adamson specializes in working with patients at high risk of melanoma, and he knew the numbers as well as anyone. While skin cancer is by far the most common type of cancer in the United States, with more than 5 million cases diagnosed annually, 98 percent of these cases are types known as basal and squamous cell carcinomas that are considered so minor they aren’t even tracked in cancer registries. They’re the kind dermatologists scrape away every day, and though they can be deeply unpleasant, they rarely require extended treatment. Basal and squamous cell carcinomas are responsible for about 2,000 deaths per year, generally in rare cases where they have been neglected for years and allowed to grow very large. Melanoma, by comparison, accounts for less than 2 percent of skin cancer cases, but about 7,000 deaths. It’s the one you don’t want to get.

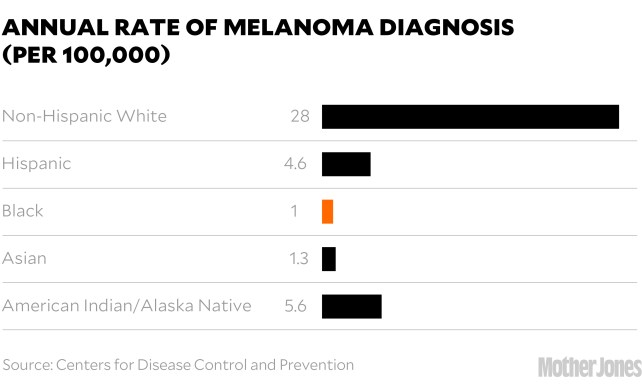

And generally, people of color don’t. The melanin in their skin is a form of natural sunblock that shields it from damage. In the United States, the incidence rate of new cases of melanoma per year is about 28 per 100,000 people in white people, five in Hispanic people, and one in Black and Asian people.

Racial categories are an imperfect way to group a wide range of people with diverse genetic backgrounds and skin tones, and the Fitzpatrick Scale—which assesses skin tone on a scale of 1 (very pale, burns easily) to 6 (very dark, never burns) has been criticized for being overly skewed toward paler skin types—but there’s a clear correlation between darker skin and lower risk of skin cancer, with people of moderately pigmented skin having a much lower risk than fair-skinned Scandinavians, but higher than dark-skinned Africans. And on the rare occasions when dark-skinned people do develop melanoma, it’s most commonly a type called acral lentiginous melanoma, or ALM, that appears on the palms, the soles of the feet, or under the nails and has no connection to sun exposure. (Famously, this is what killed Bob Marley.)

For years, Adamson, who is Black, had grown increasingly frustrated by the health care establishment’s campaigns for more sunscreen adoption in people of color. “I’d see the messaging saying, ‘You’re Black, you can get skin cancer, put sunscreen on!’ ” he says. “And I just looked at the data and thought, ‘This is bonkers.’ ”

The establishment’s position had been laid out in a 2014 paper in the Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, whose senior author was Henry Lim, a highly influential dermatologist who was on the board of the AAD and would go on to serve as its president. The paper acknowledged that “UV radiation does not appear to be a major risk factor,” for melanoma in people of color, yet still recommended they use “a daily broad-spectrum sunscreen of at least SPF 30…Sunscreens should be applied liberally and reapplied every 2 hours while outdoors.” It also recommended full-body skin checks for people of color—annually, for those over 50.

That advice was an extension of the academy’s long-standing recommendations for people with lighter skin, and it came in the midst of a well-publicized “melanoma epidemic,” in which incidence rates of melanoma have increased faster than any other type of cancer—more than sixfold in the past 40 years.

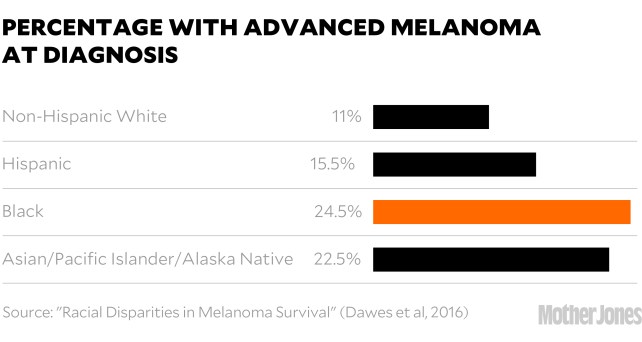

That epidemic was concentrated in fair-skinned populations, but that wasn’t the message coming from the skin care industry and the media. “Skin cancer affects people of all colors,” says the website of the industry-funded Skin Cancer Foundation, which also recommended daily sunscreen. NBC announced that “Blacks can and do get skin cancer,” and said it was essential for everyone with brown or black skin to wear SPF 30 year-round. NPR ran a story explaining that while Black people are less likely to get melanoma than white people, when they do get it, they are more likely to die from it. The advice? “Wear the damn sunscreen.”

The messaging drove Adamson crazy. He believed that the real reason people of color had lower melanoma survival rates was because ALMs have worse prognoses overall, and because many people don’t realize that spots in sun-protected areas can be skin cancer, so they don’t get them checked. It was an issue of awareness and access, not sunblock.

So Adamson wrote his op-ed. But he didn’t stop there. He also took his case to Twitter, where his natural affinity for straight talk and entertaining style set him apart from most of his peers. “Sunscreen is USELESS in melanoma prevention in dark skinned (e.g. black) people,” he began, taking readers through the basics while peppering his thread with gifs of Dr. Phil and Will Smith before getting to the heart of the matter: “If you are black, wear sunscreen to prevent uncomfortable sunburns, signs of aging, freckling, but it’s not going to reduce your already low chance of melanoma lower.”

Two months later, in an article titled “Should Black People Wear Sunscreen?” the New York Times highlighted Adamson’s opposition to the idea. Suddenly, he’d become the leader of the resistance.

After the Times article, NBC’s Today reached out to Adamson for a quote for a segment, which he provided. But the producers didn’t use it. Instead, they brought out the dermatologist Jeanine Downie, a go-to for many television programs, to rebut his points—which she did, reiterating the party line on sunscreen use: “Every day, rain or shine, January through December, regardless of your ethnicity.”

Adamson was aghast. It wasn’t the first time Today had spread misinformation on the subject. Not long before, as part of Skin Cancer Awareness Month, they’d featured a 20-year-old Black man who’d developed ALM on the sole of his foot—not sun-related, and yet he’d been chided for not wearing sunscreen.

But Today, Adamson knew, was not really the problem. Like other media outlets, they were taking their cues from the pros, and the pros were speaking as one that no drop of sunscreen should be spared in the fight against melanoma—a message the $2 billion sun care industry has been happy to endorse with new lines of products aimed at the six-sevenths of the human race that doesn’t have light skin. The only way to counter such firepower, he decided, was to do his own investigation, a comprehensive review of every study that looked at melanoma in people of color. If it showed that the sun did play a role, fine, he’d let it go. But if it didn’t—well, he wouldn’t.

Adewole Adamson (“Ade” to his friends) has been questioning official stories since he was in medical school at MIT and Harvard, which he attended after graduating from Morehouse College in Atlanta. He entered med school expecting to follow the traditional path, “But then I got to the wards. And I saw patients on a daily basis. And I was floored by how dysfunctional the system was.” The source of many his patients problems was rooted in socioeconomic inequalities best addressed long before they visited a hospital, but the system was structured around financial payments for medical procedures, so that’s what they got.

He wound up getting a masters in health care policy at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government. “It totally transformed my life,” he says. “I thought, Wow, you can actually study how health systems work as a physician.”

He chose to do so through the lens of dermatology, for lots of little reasons. “It’s one of very few areas where you can do both research and medicine. I like the science behind it. I like that you see all ages, kids to octogenarians. And there were very few people of color in it, so it was an opportunity to make a difference.”

When Adamson trained his eye on melanoma, he quickly recognized signs that something was amiss, and initially his interest had nothing to do with race. “For me it all started with a simple figure,” he says. “Melanoma incidence has gone up sixfold, and mortality has stayed flat. That never quite made sense. That was the beginning of the rabbit hole.”

The reason for the rise in incidence has remained mysterious. The sun hasn’t changed. Sunscreen use has improved. The ozone layer has been healing for years. Even tanning bed use, which modestly increases the risk of melanoma, has declined. One likely culprit is age—melanoma is mostly a disease of old white people, and the number of white Americans 65 or older tripled from 18 million in 1960 to 54 million in 2020—but that only accounts for a fraction of the increase. No obvious explanation has emerged.

As for the improving mortality, a small part of it is due to revolutionary immunotherapy treatments, which have pushed the five-year survival rates for metastatic melanoma from less than 10 percent to nearly 50 percent (see box). But most diagnosed melanomas are not metastatic. They are caught due to early intervention—a decades-long push that has led to a dramatic increase in both screenings and biopsies, which rose from 2 million to nearly 6 million among Medicare recipients over a 15-year period. Virtually all the rise in melanoma incidence has been in tiny melanomas. Many experts maintain that the massive improvement in five-year survival rates (now higher than 93 percent) is because these baby melanomas are being caught and removed before they spread.

Adamson didn’t think it was that simple. To him, exploding cases and flat mortality looked like a classic case of an epidemic of overdiagnosis. “The more you look for cancer, the more you find it,” he says.

But is it really cancer? Until a lesion becomes invasive, there’s no objective way to say what’s a melanoma and what’s benign. It’s a judgment call for the pathologist, and today’s pathologists are increasingly likely to diagnose new spots as melanomas. In one study, pathologists were asked to look at 40 biopsies and decide if they were melanoma. On average, they called 18 of them melanomas. But the exact same biopsies had been shown to pathologists 20 years earlier (including some of the same pathologists). Back then, they judged only 11 of them to be melanomas.

Another study found that dermatologists were more likely to recommend biopsies if they had an in-house lab to do the work. That type of self-referral used to be rare—and indeed, is illegal in most areas of medicine—but is increasingly common, especially with the rise of corporate dermatology. “It’s becoming more and more of an issue,” says Adamson. “In fact, it’s roiled our field over the last few years. We’re one of the specialties that’s been able to hold onto the small group-practice model where we own everything. And that’s quickly getting eaten up by private-equity firms that buy out older dermatologists’ practices for seven-figure sums.”

The $15 billion business of dermatology is increasingly dominated by megapractices run by management groups that are unabashedly profit-oriented. Those profits can be boosted by increasing the number of procedures performed, by keeping those procedures in-house, and by maximizing the use of physician’s assistants, who come cheaper than doctors. An investigation by the New York Times found that use of physician’s assistants in the country’s largest private-equity-owned practice quadrupled over a decade, and that PAs were twice as likely as dermatologists to recommend biopsies. Another investigation found that doctors working in private-equity-owned practices have reported pressure to upsell additional procedures and skincare products.

But even within traditional practices, Adamson sees a runaway feedback loop as melanoma awareness expands. “Everyone in the system is playing into the cycle. Patients want to get checked. Dermatologists want to find cancer early. Dermatopathologists want to read more slides. And they’re incentivized to overcall things. Nobody’s going to slap you on the hand if you overcall a melanoma, but if you undercall one, you might have a lawsuit on your hands.”

In other words, every part of the system benefits from calling small enigmatic lesions melanomas and removing them. Clinics profit. No one gets sued. And melanoma survival rates surge. “It’s a vicious cycle,” Adamson says. “We’re manufacturing cancer survivors.”

In a controversial paper in the New England Journal of Medicine, Adamson and two co-authors said as much. They called for an end to self-referrals and population-wide blanket screenings, and a raising of the threshold to biopsy and to diagnose melanoma.

In a response on the AAD website, Sancy Leachman, the chair of the AAD’s Melanoma/Skin Cancer Community Programs Committee, was skeptical. “Shouldn’t our call-to-action be to improve, rather than to decrease, our diagnostic scrutiny?” she wrote. “Is it appropriate to decline to biopsy something that might kill the patient, particularly if monitoring is not an option?…What we are experiencing now is a swing of the screening pendulum, produced by the recognition that we may be over-screening those at low risk; we shouldn’t wildly overshoot the center, though, by halting screening for those that will benefit.”

Adamson agrees that some fraction of the diagnosed tiny melanomas are real, and he concedes that the likelihood of dermatologists policing moles less aggressively is remote. “Cancer’s scary! That’s why this problem’s intractable in many ways.”

At least, it is in white populations, who currently get most of the screenings. But as Adamson saw more and more calls by his colleagues and the skin care industry to bring people of color into the fold of continuous skin surveillance, he decided the time had come for his deep dive into the numbers.

Adamson and his co-authors eventually found 13 studies that met their criteria. There was consistent evidence that sun exposure raised the risk of melanoma in white populations, and strong evidence that it didn’t in other groups. “All the metrics that show a signal in white people, the signal is absent in People of Color,” says Adamson. “It’s just not there. And that’s okay! It should be good news. Yet somehow I’m controversial for it.”

Jeanine Downie, the Today dermatologist, for one, is not buying it. “I disagree respectfully,” she says. “Not all melanomas in Asian Americans and African Americans are related to UV exposure, but some definitely are. My advice remains the same: Every day, rain or shine, January through December, regardless of your ethnicity, you need to wear sunblock with an SPF of 30 and reapply it.”

Yet even Henry Lim, the former president of the AAD who wrote the definitive paper on melanoma in people of color, now says he agrees with Adamson—to a point. “I think he’s correct. His analysis is very well done. If one focuses only on people of color, there’s no correlation at all between sun exposure and melanoma. So yes, specifically for melanoma, photoprotection is not essential for this group of individuals.”

But Lim says people of color should still use sunscreen to reduce their risk of basal cell carcinomas and hyperpigmentation—sunspots. Lim practices in Detroit, where he sees a lot of darker-skinned patients who are distressed by their blemishes. “Pigmentation is not a life-threatening issue,” he says, “but it is a quality of life issue.” So are sunburns, which do affect people of color and which sunscreens are excellent at preventing.

Cosmetic impacts can unquestionably produce very real social and psychological stress, but if such concerns are the primary issue (basal cell carcinoma is quite rare in people of color, and easily treated), then the message from the academy and the media needs to change. The “fearmongering,” as Adamson calls it, needs to stop.

Part of the industry’s calculus seems to be: What’s the harm? If darker-skinned people wear more sunscreen and get more skin checks, perhaps it will save a few lives.

But there is harm. Adamson has estimated that it would take general screening of 1 million Black individuals for a decade to prevent a single melanoma death, and that such a screening would result in many unnecessary biopsies, often in areas such as the palms and soles that can lead to physical impairment. Those biopsies also cost a lot of money.

And so does good sunscreen. If used as recommended—every day, rain or shine, regardless of your ethnicity, one ounce per application, reapplied after every two hours in the sun—an outdoorsy family of four could easily spend thousands of dollars on the stuff. If you have fair skin and a higher risk of melanoma, that might be a good investment. But if you have dark skin and little risk of skin cancer, it’s probably not.

Other harms are more subtle, but no less damaging. Once you’ve been told the sun is your enemy, it changes things. Adamson says he sees that happen in patients diagnosed with early-stage melanomas. “They get scared to go outside. They stop running, or hanging out with their family in the park. Those things become unenjoyable. And there are potential health costs to that as well.”

Even worse, he says, is the subtle implication that people of color are irresponsible if they don’t wear sunscreen. “Making that link makes patients feel like they are the reason they got melanoma,” he says. “It’s almost like victim-blaming. And that does not sit well with me.”

The time has come for more nuanced recommendations, says Nina Jablonski, the Penn State anthropologist who has spent her career studying the biological and social implications of skin color. “The science has changed,” she says. “We now have a much better idea of what’s going on.”

We use sunlight to produce vitamin D, nitric oxide, and other compounds in the body that improve immune function, reduce inflammation, and lower blood pressure, and we evolved dark skin as a way to do that safely. The pale skin found in northern European populations is a later adaptation to a low-sun environment, where it was no longer advantageous to block sunlight. It makes sense to tell that population to carefully limit its sun exposure, especially in sunnier climes, but extending that recommendation to people with darker skin has never been supported by the science.

“The problem,” says Jablonski, “is that many dermatologists feel it’s taken so long to get people to use sunscreen, so they’re extremely hesitant to go public with recommendations about relaxing sunscreen use. They’re afraid that people will just throw away their bottle of sunscreen, throw away their hats, and cast aspersions on the profession for having asked them to do this stuff in the first place.” But a way needs to be found, she says. “We’re going to improve overall public health much more by relaxing this guideline than by enforcing it.”

Jablonski compares the problem to the draconian diet advice of the 1990s, when experts suggested extreme low-fat diets for everyone. “A lot of people just got very irritated and said, ‘I’m not going to pay attention to this stuff.’ And that’s what we face now with these punitive, one-size-fits-all approaches. It just goes against human intelligence and human emotions, and people will reject it.”

But the failure of the low-fat campaign also showed that people are good at responding to new science that impacts their personal health, she says. “In the past 20 years, people have come to grips with fairly sophisticated information about diet. My feeling is that they can get their heads around some of the subtleties of sun exposure, too.”

Jablonski thinks the establishment should put more faith in individuals’ ability to calibrate what’s right for them. “I think it will be important to adjust these things and essentially make a prescription for personalized sun exposure and diet, depending on where you are, who you are, and under what conditions you’re living. It’ll just be part of the personalized medicine packages that we will have in future generations.”

Getting to that point without losing the progress that has been made in fighting skin cancer will be tricky, Jablonski says. “I think this will be done, but it’s going to be done in dribs and drabs over the course of the next decade.”

Adamson may play a key role in that effort. After publishing his opinion pieces and tweets, he was invited to join the American Academy of Dermatology Task Force on Skin Cancer and Skin of Color. That move, he believes, “hints at the possibility they’re open to reconsidering the evidence.”

This summer, in JAMA Dermatology, Adamson and two dermatologists from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center laid out “an alternative call to action.” Instead of pushing more sun-awareness campaigns and screening programs, they suggested focusing on the structural disparities: Education campaigns and improved access to health care, so that people of color don’t wait to get suspicious lesions checked; more inclusion of skin of color in scientific studies and clinician training, so that the particularities of cancer in skin of color are recognized; and new therapies for treating ALM, which has remained frustratingly deadly.

Adamson says he has no idea if anyone will take him up on these suggestions. “I’m a peon, man! I’m just a junior attending. I have no power. All I can do is put these ideas out there.” But he also expected to get slammed by the establishment, and instead has been surprised by the mostly positive response, which he thinks bodes well for the future. “People are at least willing to engage and think about what they’re doing. And that’s not nothing.”