Abbe Lowell attending the September 1, 2018, funeral of Sen. John McCain (R-Ariz.)Tom Williams/CQ Roll Call

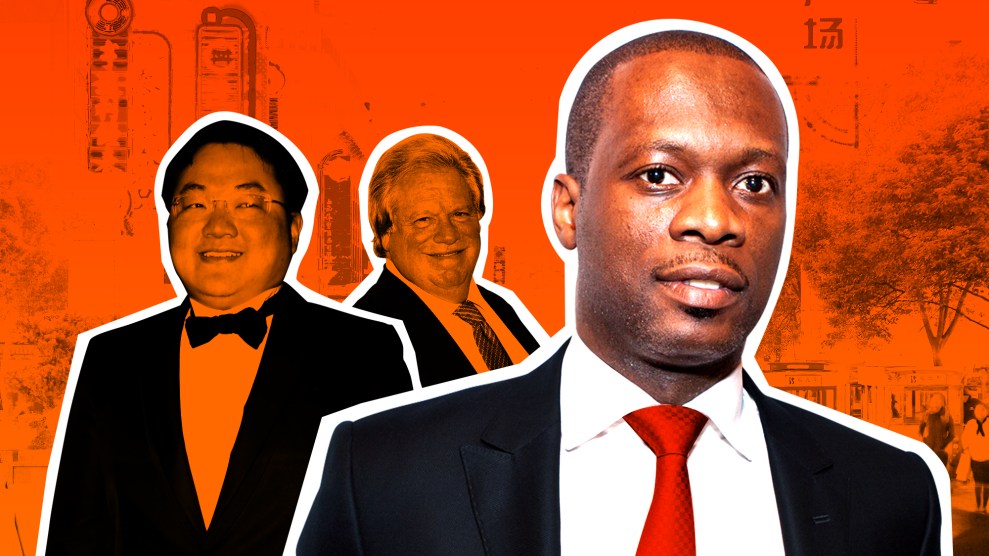

Abbe Lowell, one of Washington’s top attorneys, has spent decades helping high-profile clients engulfed in political scandals. But now Lowell—known for representing Jared Kushner, Sen. Robert Menendez (D-N.J.), John Edwards, Jack Abramoff, Bill Clinton, and others—is himself the subject of a controversy.

Last summer, Lowell negotiated a plea bargain with the Justice Department for Nickie Lum Davis, a Hawaii businesswoman and GOP fundraiser who had engaged in illegal lobbying. In April, Davis fired Lowell without public explanation. And a new lawyer representing her tells Mother Jones that Lowell failed to disclose a conflict of interest to Davis prior to her guilty plea.

Lowell denies this allegation. And many details of the issue are disputed. Still, the unusual spat offers a glimpse into the small and interconnected world of DC power lawyers. At the heart of this scuffle is the allegation that a plugged-in attorney with a slew of prominent political clients failed to tell one of those clients about what could be perceived as a personal interest in her case.

On August 31, Davis, with Lowell representing her, pleaded guilty to assisting in a scheme to illegally lobby the US government on behalf of Malaysian interests. Davis, who awaits sentencing, agreed to forfeit $3 million. She faces a potential maximum of five years in prison, though prosecutors have recommended she serve at most a few months.

Davis agreed to cooperate with prosecutors who were eager to use her as a witness against a bigger target, Elliott Broidy, a former top fundraiser for Donald Trump and deputy finance chair of the Republican National Committee. Davis admitted that she had helped Broidy avoid registering as a foreign lobbyist, even as they accepted millions of dollars from a Malaysian businessman to help Malaysia’s then–prime minister, Najib Razak, push Trump to block a Justice Department investigation into Najib’s embezzlement of money from a state investment fund. (Najib was later convicted on corruption charges in Malaysia.) Davis’ cooperation helped prosecutors convince Broidy to plead guilty to conspiring to violate foreign lobbying laws. (Broidy resigned from his RNC job in April 2018 due to a personal scandal.) Trump pardoned Broidy in January. Davis, who last year paid at least $100,000 to a Trump-linked lobbying firm to pursue a pardon, did not receive one.

Lowell was well acquainted with Broidy when he brokered Davis’ plea. In fact, in late 2016, Broidy had persuaded Lowell to work for Sanford Diller, a San Francisco–area billionaire who was seeking help convincing the then-incoming president, Donald Trump, to pardon a friend of his. This pal, Hugh Baras, was a Berkeley psychologist facing a prison sentence for tax evasion and improperly receiving Social Security benefits. Lowell relayed materials advocating the clemency request to the White House Counsel’s Office shortly after Trump’s inauguration, the Wall Street Journal reported. Lowell did not succeed, and Baras went to prison in June 2017. He was released two years later.

The effort to secure a pardon for Baras led to an investigation by Justice Department prosecutors. According to a December 3, 2020, New York Times report and a heavily redacted court filing unsealed two days earlier, prosecutors investigated the roles of Broidy and Lowell in a suspected scheme in which Diller, who died in 2018, would make what prosecutors described as “a substantial political contribution” to an unspecified recipient in exchange for Baras’ pardon. Prosecutors also examined if participants in this effort had violated lobbying laws. They questioned whether Lowell should have registered as a lobbyist in connection with his outreach to the Trump administration regarding Baras, according to a person with knowledge of the matter.

Reid Weingarten, another prominent DC lawyer who represented Lowell regarding this pardon investigation, said in December that the Justice Department “investigated and concluded that nothing was amiss” related to Lowell’s advocacy for Baras. “I came away thinking this is bullshit and he’s not in the least bit of trouble,” Weingarten tells Mother Jones. A lawyer for Broidy said in December that Broidy’s only involvement in this pardon matter was introducing Lowell to Diller.

The duration of the Baras pardon investigation is unclear. But court records show that prosecutors were pursuing what US District Court Judge Beryl Howell called a “bribery for pardon” investigation, which the Times revealed was linked to Baras, in the summer of 2020. At an August 25, 2020 hearing, prosecutors sought permission from Howell to review Lowell’s communications with others involved in the pardon push. Asking a judge to allow review of a lawyer’s private communications is an extraordinary request, suggesting that prosecutors took the pardon matter seriously. Howell granted that request a few days later.

Davis pleaded guilty less than a week later, on August 31. That means that Lowell was negotiating this plea deal at the same time prosecutors were investigating him. In addition, the prosecutors who conducted the pardon probe involving Lowell worked in the same Justice Department unit, the Public Integrity Section, as those prosecuting Davis. And prosecutors in the pardon probe were managed by the deputy head of the unit, John Keller, who also oversaw Davis’ prosecution and negotiated her plea deal with Lowell, according to a person familiar with the talks. Keller declined to comment, as did a Justice Department spokesperson.

This raises the question of whether Lowell at the time of the negotiations in the Davis case had a personal interest in possibly helping a Justice Department that was then looking into his own actions—a matter he would need to tell Davis about before she completed her plea.

Davis did sign a conflict-of-interest waiver prior to completing her plea deal. That document said “the United States Department of Justice has raised with one of her attorneys, Abbe D. Lowell, his previous representation of certain individuals with whom Ms. Davis also has had contact or interactions and whose names have or might come up during her cooperation and of certain other individuals on matters unrelated to Ms. Davis.” The filing says Davis “knowingly and intelligently waives any potential or actual conflict of interest as to Mr. Lowell.”

But James Bryant, a lawyer now representing Davis, says Lowell did not inform Davis of any potential conflict related to his efforts to help Baras secure a pardon. Politico, which first reported on this dispute between Lowell and Davis, noted that Davis told associates she believed the waiver related to Lowell clients unrelated to the pardon investigation. This would mean Davis was not aware that Broidy, who she cooperated against, was a potential witness in a probe in which her own lawyer’s actions were under scrutiny.

“This conflict was never disclosed to Nickie any time prior to entering her plea.” Bryant tells Mother Jones. “She only learned about it when the New York Times article [about the Justice Department’s pardon investigation] was published. Upon learning of the Baras investigation, Abbe should at a minimum have fully disclosed everything he knew to her and given her the choice of whether to keep him as counsel or not.”

Asked to respond, Lowell says, “I cannot comment on client communications. However, the statement is simply wrong and unfair, as I acted appropriately at all times.”

This controversy hinges on when Lowell became aware he was the subject of the Justice Department’s pardon probe and what he knew while negotiating Davis’ plea. These details are not clear. Lowell declined to say when he learned of the investigation. But two people with knowledge of the matter said Lowell was informed of the investigation prior to Davis’ August 31 plea bargain.

George Clark, who practices ethics and professional responsibility law in Washington, DC, says that a lawyer negotiating a plea deal for a client while prosecutors are also investigating him would have a conflict. “If a lawyer has his or her own personal interest in a matter in which he is representing a client, then that lawyer has a conflict of interest,” Clark explains.

Lowell retains a thriving practice, and he has previously acknowledged feeling stung by criticism. In a December op-ed published in American Lawyer, he complained of a harsh partisan climate and argued that reports on his work for Baras and criticism of his actions occurred “primarily because I later represented a different client, the president’s son-in-law.”