Click the highlighted text for more.

Last December 7, Michael Savage kicked off his radio program by railing yet again against the “demonic” and “fascist” governors who had locked down their states to slow the spread of COVID. Yet on that day, the host of The Savage Nation launched a new line of attack inspired by the anniversary of the bombing of Pearl Harbor—and the United States’ reaction to it. Broadcasting from his home in Northern California, where a strict new stay-at-home order had just gone into effect, Savage declared that his and other blue states had been turned into “Democrat-run prison camps” whose residents were living under “undeclared martial law.” “We have gone from Japanese internment to lockdowns and curfews without so much as anyone screaming,” he said.

Riffing on this tendentious analogy, Savage said he hoped that the governors of California and New York “don’t declare their states military areas from which any or all persons may be excluded”—a reference to the orders that led to 110,000 Japanese Americans being forced into concentration camps during World War II. “Maybe they’ll deport us from our own state, making it safe only for Mexican illegal aliens so they could have 100 percent and absolute freedom to do what they want.”

The harangue thinly disguised as a history lesson was typical of Savage, a right-wing shock jock whose 27-year career has left a trail of racist, xenophobic, and homophobic comments. But the pseudonymous talker (real name: Michael A. Weiner) wasn’t simply mouthing off as his on-air persona; he was about to enlist his audience in a battle he’d been waging in his side gig as a public servant.

Last May, President Donald Trump named Savage to the board of directors of the Presidio Trust, the federal corporation that runs the nearly 1,200-acre urban park at the foot of San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge. In a normal year, as many as 10 million visitors enjoy the Presidio’s stunning views, forests, wetlands, and historic sites. For more than a century, this prime real estate had been an US Army base; in 1994, the Pentagon handed it over to the National Park Service. When his appointment was first announced, Savage said that one of his goals would be to “remind the public of the military significance” of the site. Yet throughout the fall of 2020, Savage had been working behind the scenes to use his new position to try to downplay an inglorious chapter of that history: the former base’s inarguable connection to the forced removal and detention of Japanese Americans during World War II. That abuse of power, set in motion by a 1942 executive order signed by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, was carried out through more than 100 military exclusion orders issued from the Presidio—orders just like those Savage had alluded to on the air.

His revisionist campaign was focused on the Presidio’s museum, which he had come to see as a symbol of unchecked liberal sensitivity. “You would think that the military heritage museum would show us the greatness of the US Army at the Presidio, but it doesn’t,” he griped on his December 7 program. “Instead, it shows us big things about the Japanese internment. Two of the largest exhibits inside this heritage museum are about the internment of Japanese Americans. Now as important as that is, it does not define the US military.” To rectify this “cockeyed” and “crazy” situation, Savage said he wanted the museum to highlight events such as D-Day and the liberation of Nazi concentration camps.

He went on, quickly heading toward one of his trademark apoplectic blow-ups. “I am so sick and tired of the vermin on the left debasing the military in my country that I could just scream about it!” he shouted.

The rant wasn’t just for effect. A trove of emails obtained through the Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) reveal that Savage’s first months as a Presidio Trust board member were marked by prickly outbursts, culminating in a sudden push to inject his toxic politics into park business. And, as he promised his audience on Pearl Harbor Day, he’s only getting started. “I’m on for another three years on the Presidio Trust board and I’m going to kick my heels up and raise hell until the US Army is represented properly inside that museum,” he said. “You have only heard the beginning of my outrage.”

Michael Savage, pictured here in 2007, said he did not ask Trump to put him on the Presidio Trust board.

John Storey/AP

In his final year in office, Trump handed out dozens of positions and awards to loyalists whose qualifications included their propensity to irk liberals. But amid the worsening news during the first weeks of the pandemic, Savage’s appointment to the Presidio Trust’s board prompted little comment, even in the city he calls “Sicko Frisco” and “San Fran-Freako.” Perhaps it was just a coincidence, but the March 26 announcement fell on the birthday of House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, a key player in the Presidio’s conversion into a national park and a frequent target of Savage’s bile.

The new job was the ultimate validation of Savage’s transformation into the self-styled “Godfather of Trumpmania.” The 79-year-old got his start in talk radio in the mid-1990s with a drivetime show in San Francisco. In less than a decade, he gained a national audience, got and lost a show on MSNBC, and joined the top ranks of conservative radio hosts. He was initially cool toward Trump, whom he mocked as “the Balding Eagle.” Yet he changed his tune in 2015, becoming an early and ardent supporter of a presidential candidate whose white identity politics and constant need for affirmation mirrored his own. Trump repaid Savage’s allegiance with audiences at Mar-a-Lago, the White House, and on Air Force One. Even as Savage criticized Trump for not going far enough, he portrayed the political forces arrayed against the president in apocalyptic terms. “At the end of the road,” he warned as the 2020 election approached, “we know Trump is the only thing standing between us and absolute chaos in this nation.”

The president names six of the Presidio Trust’s board members; the secretary of the interior designates the seventh. The unpaid four-year seats have mostly been filled by affluent Bay Area residents: President Barack Obama’s appointees included investment banker William Hambrecht, a major Democratic donor, and Mark Pincus, the founder of the gaming company Zynga. Savage, who lives just outside San Francisco in Marin County, replaced John Keker, a high-profile attorney. Four of his colleagues on the board are Trump appointees with conventional CVs; Lynne Benioff, a philanthropist who is married to Salesforce CEO Marc Benioff, is the sole remaining Obama appointee. (The seventh member is the former chief of staff for ex-Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt.) According to the trust, only the president may remove or replace sitting board members.

By law, the board’s seats must go to people with “extensive knowledge and experience” in city planning, finance, real estate development, or resource conservation. Presumably, Savage checks that last box; he’s said Trump picked him specifically for “the resumé of my environmental background over the last 40 years.” Ironically, that’s the one issue where there is the most political daylight between Savage and Trump. Though he detests the “Environmental Propaganda Agency” and thinks climate change is a “scam” based on “Stalinist science,” Savage is a Rachel Carson–quoting animal lover who spoke out against Trump’s decision to allow the hunting of bear cubs and wolves on federal land and against his sons’ trophy hunting. “Their record on the environment is sickening, abysmal, nightmarish,” Savage said last June.

Most of Savage’s conservationist cred stems from his pre-radio career, back when he was a hippie, herbalist, nutritionist, and the author of books like Plant a Tree and Herbs That Heal. Savage has always flaunted these unusual credentials, which he’s burnished to a high gloss. He has claimed to have “spent decades searching and saving tropical rainforests.” His bio states that he has a PhD from the University of California, Berkeley, in “epidemiology and nutrition sciences.” (Officially, it is in nutritional ethnomedicine.) Lately, as he’s claimed that COVID surges are caused by Mexicans trying to “flood the gringo hospitals” and has vowed to “join an armed militia” before getting vaccinated, he’s boasted of being “a trained epidemiologist.”

Savage has bragged to his listeners that his position at the Presidio Trust is “equivalent to being an ambassador.” The prestigious post arrived at an opportune moment. As 2020 came to an end, so did The Savage Nation, which aired its final episode on December 31. (Savage said “legal reasons” prevented him from saying why Westwood One pulled the broadcast.) Though he now hosts a twice-weekly podcast, he’s lost a major platform for amplifying the kinds of controversy that have sustained his career. As he ventured into “this piece of federal land in the middle of occupied territory,” he would find a new one.

In a normal year, as many as 10 million visitors come to the Presidio.

Getty

When his appointment to the Presidio Trust was made public last March, Savage insisted it wasn’t his idea. “I did not apply for it, didn’t ask for it,” he claimed on his program. When Trump personally called to make the offer, Savage said that he’d promised, “President Trump, I’ll make you proud.”

Yet Savage seemed unprepared for his new role overseeing a popular park that receives no federal funding and was facing a pandemic budget crunch. “When I talked to him he had no idea we run a large business to be self-sustaining,” Presidio Trust CEO Jean Fraser, who was appointed by the board in 2016, wrote in an internal email after her first conversation with him. Board Vice-Chair Marie Hurabiell, who was appointed by Trump in 2018, spoke with Savage and reported back that he “seemed very excited to be working with the Presidio, which he loves.” But, she continued, “He was a little nervous that it would be a lot of work and asked how we all manage it.” Savage was initially assigned to the board’s finance and audit committee, but he demurred. “I am not a financial person,” he replied. (He joined the governance and human resources committee instead.)

Prompted for details on what he would like to do with his new role, Savage, who has no military experience, emailed back that he hoped to see “a new inclusion of the Presidio’s proud military heritage” and wanted to use his botanical knowledge to create “a native American medicinal plant garden.” Asked for examples of his personal ties to the park to include in a press release, he suggested quoting his 2012 action novel Abuse of Power, in which the former base is a backdrop for a high-speed chase along roads named “for military commanders who knew how to defeat the enemy, not placate the media and foreign lobbyists.”

Savage proved easily fazed by routine requests. When he was asked to attend a short ethics review with a staff attorney, he grumbled, “What is this emphasis on ‘ethics’? Am I somehow suspect?” The session, he was told, was mandatory for new board members. Savage, writing from a personal email account with the handle “joe shmo,” replied, “Well i can understand the need for this procedure. But I find it offensive to answer to some lawyer.” (He eventually relented and took the training.)

When he was told he’d have to fill out a standard financial disclosure form, Savage balked. “SINCE I AM NOT AN EMPLOYEE OF THE U.S. GOVERNMENT, NOR RECEIVING ANY COMPENSATION I SEE NO NEED TO FILL OUT THE ‘ETHICS’ FORM,” he wrote. After he was granted an extension, Savage said that he and his wife “are in touch with the White House about this intrusive inquisition…To open up our PRIVATE financial arrangements, for a non-paying relationship, and expose ourselves to unknown individuals is not tenable. Especially in these troubling times.” (He eventually submitted the form, which is not public.)

When it came to board business, however, Savage was less eager to make use of his connection to Trump. Last June, as a funding bill for the national parks moved through Congress, the trust’s board members were asked to work their connections to push for an amendment allowing the Presidio to increase its borrowing authority. The money would have provided a financial lifeline to the park, which lost $29 million in revenue last year and laid off 20 percent of its 350-person workforce. Carole McNeil, a real estate investor put on the board by Trump in 2019, got in touch with Sen. Lindsey Graham (R-S.C.), who she thought “would probably take a positive interest in our situation.” Yet when a Presidio Trust executive asked Savage if he’d hit up his “contacts in the White House,” his response was unenthusiastic. “I will just forward your letter to the White House,” he wrote. “Doubt the timing. Riots have the entire admin occupied.” The final version of the $1.9 billion Great American Outdoors Act did not include the Presidio’s request.

To his obvious displeasure, Savage’s new position also opened him up to an unfamiliar type of scrutiny. When an internal report disclosed one of the FOIA requests used to report this article, Savage sent an irritated email to Fraser. “What’s the situation surrounding ‘Dr Weiner’s emails to Board staff’?” he demanded, referring to his legal name, which he uses on the board. “Why is this an issue? Who sent this? What is the resolution?”

On July 23, Savage attended his first public board meeting, held via Zoom. During the comment period, one of the Presidio’s residents began to speak about how Savage’s well-documented views relate to the trust’s diversity, equity, and inclusion plan. She calmly noted that the Southern Poverty Law Center has reported that Savage “subscribes to the white genocide conspiracy theory” and has blamed immigrants for spreading disease. She had started to describe his comments about Muslims when board chair William Grayson, a wealth manager appointed by Trump in 2017, cut her short, saying that bringing up board members’ personal views was “outside the scope” of the meeting.

The speaker was silenced after less than a minute, but this exposure to a small dose of public criticism incensed Savage. After the meeting, he fired off an email to Grayson and trust administrators demanding, “WHO PERMITTED THE LAST SPEAKER TO ATTACK ME? HOW DID SHE GET ON THE LIST OF ‘APPROVED SPEAKERS’?” Fraser responded that public comments at board meetings are not pre-screened. “[W]e are required under the First Amendment not to censor people however offensive their comments might be,” she wrote. Savage snapped, “Yes, I am aware of the ‘law’. Do not appreciate your lecture. Not what I asked. How did this hateful person get to be chosen?…Did she indicate she wanted to verbally abuse my good name?” Fraser emailed Grayson and Benioff that she would appreciate their assistance “in helping Dr Weiner understand how public meetings work.”

In an all-caps message, Savage suggested new rules for the board’s public meetings, including a prohibition on “AD HOMINUM [sic] ATTACKS ON BOARD MEMBERS” as well as any discussion of their political or personal views. Afterward, the board posted updated meeting guidelines that expressly ask members of the public to “not address individual Board members.”

Savage at a restored marsh in the Presidio in December 2020

Presidio Trust, via Freedom of Information Act

In his messages from his first few months at the Presidio Trust, Savage comes off as thin-skinned and crabby, yet largely able to keep his political agenda separate from board business. However, that boundary collapsed last fall, when he found an outlet for one of his long-simmering fixations.

At the board’s public meeting on September 23, Fraser announced a plan to save money by moving the Presidio’s museum, known as the Heritage Gallery, from its home in the old Officer’s Club to a smaller space. Several members of the public spoke out against relocating the museum, which includes exhibits on the indigenous Ohlone people and the Presidio’s time as a Spanish and Mexican garrison. None of the speakers were critical of the gallery’s content; two specifically praised “Exclusion,” a recent temporary exhibit that explored the former Army base’s “pivotal role in the incarceration of Japanese Americans.” “I’ve seen people cry,” after seeing it, one docent said. “I’ve seen people come in and thank us for raising the issue that they feel is extremely important.”

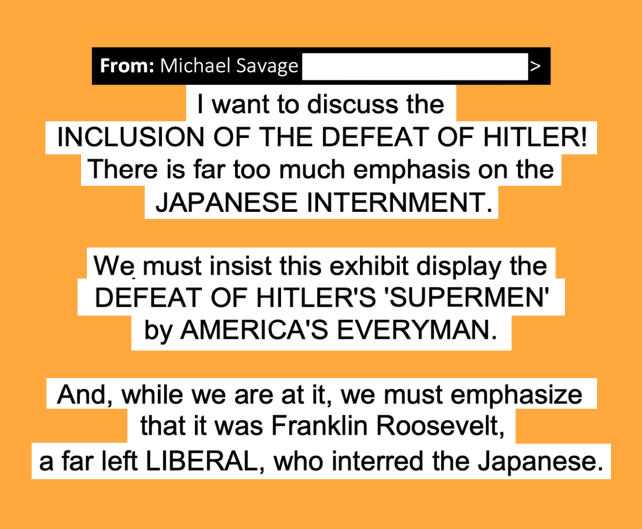

In their emails about the plan, board members, including Savage, expressed their desire to keep the museum in its current location. Yet shortly after the board meeting, Savage dragged the conversation off on an irate tangent, writing to his colleagues, “Now that we are looking more closely at the Heritage exhibit, I want to discuss the INCLUSION OF THE DEFEAT OF HITLER! There is far too much emphasis on the JAPANESE INTERNMENT.” He went on: “And, while we are at it, we must emphasize that it was Franklin Roosevelt, a far left LIBERAL, who interred the Japanese. We must insist on HISTORICAL truths. When can we address these concerns?”

On his radio program that day, Savage briefly mentioned the debate over moving the museum, implying that he was preventing a purge of the Presidio’s past: “Now, what if the president had been Obama and he had appointed someone to the board? They would remove the military history probably into a garbage can.”

The next day, Savage sent the board a message with the subject “from a military historian and war hero.” “The one thing I have found interesting is how the Trust has always been able to find a grievance to exploit,” it read. “Was it regrettable that the Japanese were interned? Yes, but the reason is more nuanced than the ‘racist’ one they will give you.” It included a link to what was described as “a government publication on the extent of Japanese espionage on the US West Coast” during World War II; in fact, it was a 1983 newspaper article hosted on the CIA website that claimed “a substantial number” of Japanese Americans had been spies. It also linked to a page about the 1941 “Niihau incident,” in which Japanese Americans in Hawaii aided a downed Japanese pilot after the attack on Pearl Harbor, an episode that was cited at the time to justify questioning Japanese Americans’ loyalties. “You probably know about this already,” the email concluded. “None of that ever showed up in any of the Trust’s exhibits.”

Apparently, Savage’s messages were met with silence; none of his fellow board members responded to his comments via email. While his angry explosion might have caught them by surprise, it didn’t come out of nowhere. Learning about the Presidio museum’s coverage of the incarceration of Japanese Americans appears to have triggered one of his obsessions. For years, Savage has fantasized about summarily locking up his enemies and trampling on their civil rights, while simultaneously insisting that liberals are secretly plotting to throw white conservatives into concentration camps.

“Americans must give up some civil liberties in order to catch those who would kill us and then we get our civil liberties back,” he wrote in his 2004 book The Savage Nation, where he unapologetically called for targeting Muslim Americans to combat terrorism. “I’m not gonna mince words with you. I want racial profiling, and I want it now.” In his following book, The Enemy Within, he stated, “We cannot afford to be naive or worried about tolerance when our national security is on the line.” Throughout last summer, he railed against Black Lives Matters protesters as “thugs,” “feral dogs,” and “vermin” who should be “rounded up” and “put into detention immediately.”

Savage has cited the imprisonment of Japanese Americans and other historical violations of civil liberties to justify his demands. After terrorists killed eight people in a van and knife attack in London in June 2017, he said hundreds of “Islamists” were on US watchlists, and asked, “Why don’t you intern all of them before they run people over on a bridge, or stab people in the street? It was done during World War II.” Last May, Savage suggested that Trump take a page from President Abraham Lincoln’s wartime crackdown on the press to “close down Twitter [and] arrest the heads of CNN.”

As an alternative to “fascist” stay-at-home orders, Savage has promoted the “selective quarantine” of communities he believes to be vectors of the coronavirus, specifically “the homeless and illegal immigrant populations.” Speaking about unhoused people last March, he said, “For six weeks I’ve been screaming, ‘Round them up, isolate them, give them the treatment they need.’ Don’t let them infect the whole city.” In September, he complained that Democratic politicians wouldn’t implement his solution because they were afraid of offending people: “So the governors, being the cowards that they are, applied affirmative action and locked everyone up in their houses and turned everyone into a prisoner.” (“I’m a trained epidemiologist,” he added. “I know more about this than anyone in the media.”)

In January, Savage joined the conservative media freakout over a New York assembly bill that proposed “the removal and detention” of people “who are or may be a danger to public health.” Though the bill would do what he’d been advocating, Savage called it the “most un-American piece of legislation ever proposed in the history of this country” and warned that it would lead to “COVID concentration camps” for white Americans. Even as he attacked the bill (which had little chance of passing) he continued to call for “an emergency decree” to forcibly detain “the homeless filth.”

Savage’s views on Japanese American internment are similarly incoherent. His 2018 book, the unselfconsciously titled Stop Mass Hysteria, details the widespread anti-Japanese sentiment that drove “blameless people” into internment camps in 1942. Savage then slams actor and activist George Takei, a survivor of the camps, for daring to make the same essential point while criticizing Trump’s Muslim ban. “Takei is not correct,” Savage writes. “[T]he internment was neither racist nor hysterical on the part of the government. It was ultimately wrong, but it was tactical and reasoned.”

Savage’s stance isn’t about consistency but convenience: The wartime mistreatment of Japanese Americans provides further proof of liberal treachery as well as cover for his own authoritarian leanings. However, if anyone, particularly survivors, asks for a sincere reckoning with this episode of paranoia and scapegoating, they are un-American whiners. On his December 7 program, Savage noted that the federal government had also violated some Italian and German Americans’ civil rights during World War II. “You don’t know any of it because the Italians and the Germans didn’t complain,” he lectured his listeners. “They didn’t cry. They didn’t demand reparations. They understood why it was done.”

When I recently asked Savage for an interview about these issues, he wrote back, “Given the extreme left wing bias of ‘mother Jones’ [sic] I would assume you want to paint me in a negative light?” A few hours later, he tweeted about Japanese American internment for the first time in more than three months: “FDR – Biden’s HERO, enslaved Japanese-Americans and placed them in INTERNMENT CAMPS! TIME TO REMOVE FDR’S name from all HIGHWAYS, SCHOOLS & Institutions.”

Since last spring, the Presidio Trust had been tracking Savage’s media appearances for any mentions of the park or his work there. A summary of his Pearl Harbor Day show that was circulated internally set off a flurry of emails among trust employees. One of the docents who had taken Savage on a tour of the Heritage Gallery in November expressed concern about his comments. “We heard some, but not all, of this criticism during the tour,” they wrote. “We told him that it was appropriate for the Presidio’s collection to focus on the Army’s history at the Presidio and let other museums, most notably the Smithsonian and other national collections, tell a more comprehensive story. Mr. Weiner didn’t seem to be very receptive to that position during the tour.”

In a message to Michael Boland, the trust’s chief park officer, another staff member wondered if Savage understood that the “Exclusion” exhibit was temporary and that the Heritage Gallery focused exclusively on the Presidio’s history. “Sigh,” Boland answered. “We’ve told him multiple times.” Other emails show that Fraser and administrative staff scrambled to talk offline about Savage’s comments, which Boland noted were “a Board governance issue.”

Savage didn’t mention the museum issue on the air again in 2020, but he had not moved on. On New Year’s Eve, he sent an email to his colleagues on the board, thanking them for “a great introduction to the intricate workings of the Presidio.” Looking ahead, he wrote, “I hope to see a greater respect for the contributions of the U.S. Army and it’s [sic] legacy on this hallowed ground.” Once again, he proposed shifting the focus of the Heritage Gallery to Army history and suggested some more exhibits with no clear connection to the park’s past: a “diorama of the Battan [sic] death March” and perhaps something on “the experiments on our live human soldiers by the Japanese military.” He added, “Let me know how I might help.”

This time, Grayson, who had not previously expressed support for Savage’s views in the messages released by the Presidio Trust, responded with enthusiasm. “I concur with Michael,” he wrote back on January 2. “Celebrating the US Army at the Presidio (and the men and women who served there—and their impact around the world) would be fabulous.” He sketched out some ideas for an expanded and improved museum. And he already had someone in mind to spearhead the project. “We need a board champion and I nominate Michael,” Grayson wrote. McNeil concurred. “I agree with you,” she said. “I think Michael Weiner would be the perfect person.”

If the other board members objected to these proposals—or the notion that Savage was seeking to champion the Presidio’s history rather than twist it for his own purposes—they did not immediately express their reactions via email. (The messages I obtained go through January 20.) I asked to speak with the trust’s board members about their responses to Savage’s opinions on the museum and the internment of Japanese Americans; a spokesperson said that they “do not discuss Presidio Trust matters with the press.” In a statement, the trust said that “There are no plans to change the content of the Heritage Gallery’s permanent exhibit” and that there has been no decision whether to close the “Exclusion” exhibit or make it permanent. After I requested an interview with Savage, I received a voicemail from a trust employee, who said that “Dr. Weiner is not a spokesman of our organization in any way.”

As 2021 began, Savage’s on-air career had faded and his political benefactor would grudgingly leave the White House in less than a month. Yet he seemed to be relishing the prospect of continuing to push buttons and boundaries inside the heart of “the sickest city in the world.” Trump’s parting gift to him still had plenty of time left on it. There was, Savage eagerly wrote to Grayson, “so much to plan for.”