The carpenters training facility near Pittsburgh looked just like the sort of place where President Joe Biden would roll out a jobs and infrastructure plan. There was the circular saw perched on a workbench, easy to spot near the phalanx of American flags behind Biden’s lectern. The emblem of the carpenters’ union, a jack plane within an interlocked ruler and compass, hung high on the wall, perfectly framed in photographs of the president in profile. And then, of course, there was the location itself: Pittsburgh, a city still synonymous with the grind and glow of steel manufacturing more than half a century after much of the industry had left.

The setting matched the string of Bidenisms the president unspooled early in his remarks. “Wall Street didn’t build this country,” Biden declared. “You, the great middle class, built this country, and unions built the middle class.” But something happened halfway through his speech. The optics conjuring white men in hard hats no longer applied. Biden spoke of the “enormous financial and personal strain” families faced trying to care for children and aging parents. He talked about the professional caregivers—”disproportionately women, and women of color, and immigrants”—who have been “unseen, underpaid, and undervalued.” There in the carpenters training center, a new working class was being joined to the cultural memory of the old one.

Biden’s plan has plenty of line items that conform to the “infrastructure” of the popular imagination: Roads and bridges got their due, and Amtrak Joe called for an $80 billion boost in funding for trains. But about a fifth of the $2 trillion in the American Jobs Plan was devoted to “caregiving infrastructure,” Biden’s term for the ecosystem of workers and services that take care of older and disabled Americans. That proposal, Biden promised, would provide “better wages, benefits, and opportunities for millions of people who will be able to get to work in an economy that works for them.”

Within days, Republicans had seized on the caregiving provisions as their main line of attack. “When people think about infrastructure, they’re thinking about roads, bridges, ports, and airports,” Sen. Roy Blunt (R-Mo.) told Fox News the Sunday after Biden’s announcement. “President Biden’s proposal is about anything but infrastructure,” Sen. Marsha Blackburn (R-Tenn.) tweeted, pointing specifically to the $400 billion Biden had designated for “elder care,” in her terms. “I don’t think any of those things are infrastructure, but you know what is??? THE WALL,” tweeted Donald Trump Jr., a characteristically oafish response to Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand’s (D-N.Y.) assertion that caregiving, child care, and paid leave all counted as such.

The Washington press corps soaked up the debate and even began to referee it. A week after Biden’s announcement, Politico declared the caregiving portion of Biden’s proposal “not even close to infrastructure.” Democrats countered by portraying the GOP as old fuds unable to grapple with the realities of a 21st-century economy. “Infrastructure is not just the roads we get a horse and buggy across,” White House Press Secretary Jen Psaki quipped during a briefing.

The semantic argument obscured a remarkable aspect of Biden’s proposal: It’s the first time a president of either party has attempted an economic recovery focused on women workers. In the coming weeks, the White House plans to release another plan that is expected to include similarly sweeping changes to how the country addresses child care and paid family leave. “There is a real recognition, in a new way, of how not investing in care is a huge liability for our economic health,” Rakeen Mabud, chief economist of the Groundwork Collaborative, a left-leaning think tank, tells me. “It’s actually really, really great for our economy, and supports some of the people who have historically been most left out in our labor market policies.”

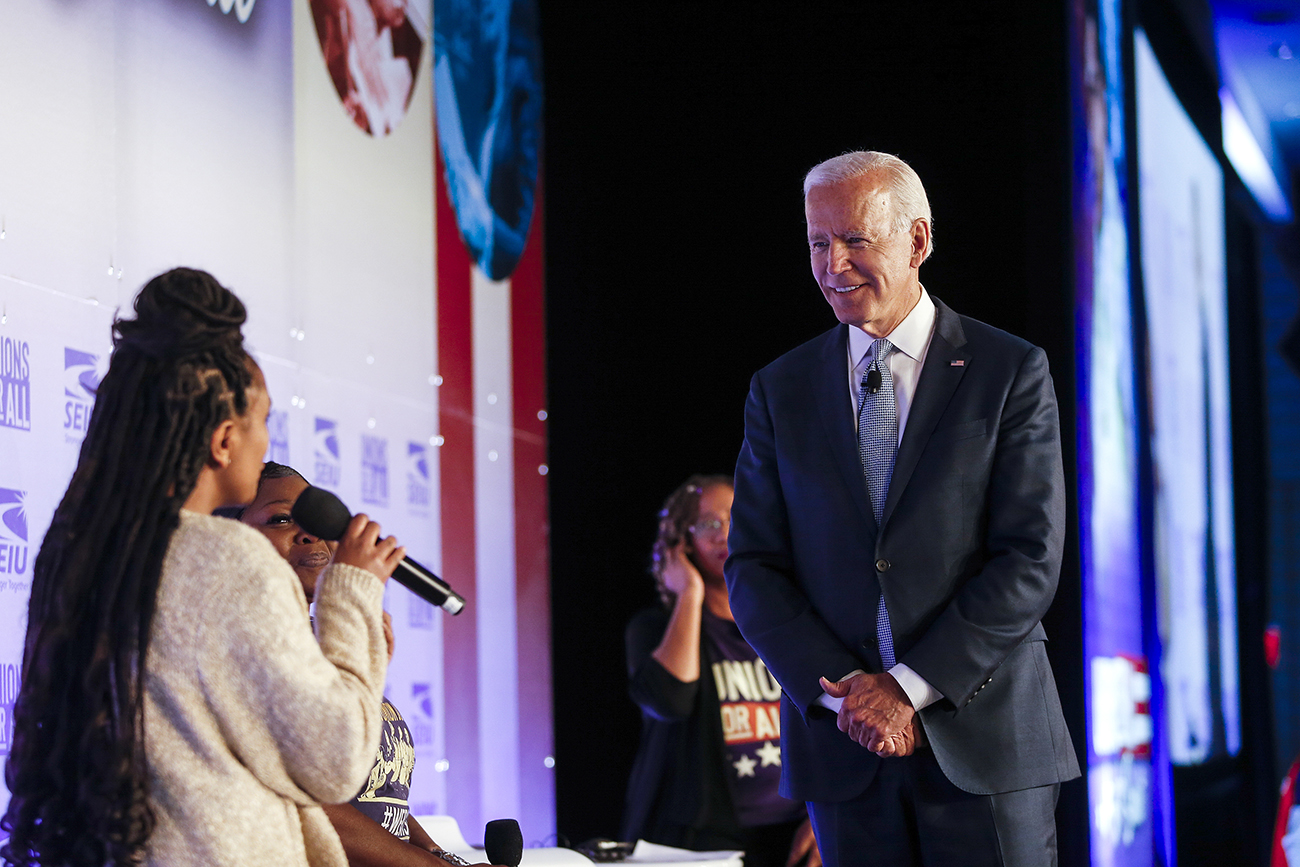

Joe Biden speaks at a SEIU summit 2019.

Ringo H.W. Chiu/AP

Less than a fifth of FDR’s Works Progress Administration jobs went to women in the 1930s. President Obama’s economic advisers initially estimated 42 percent of the jobs created by his 2009 stimulus package would go to women, but during the first two years of recovery, men gained 768,000 jobs and women lost 218,000. Since Obama tackled that last crisis, however, there has been a profound shift in how work that’s typically coded female gets assessed in terms of the overall economy. “The potential here is actually transformative,” says Ai-jen Poo, the executive director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance. “Because we think about it from an economic standpoint, investing in good care jobs is not only beneficial to those workers and their families.” There’s also been a shift in the nature of the crisis itself: By some estimates, the pandemic has set women’s economic equality back a whole generation.

It hasn’t been easy to get Democrats to accept care as infrastructure; Biden and some of his aides struggled with the concept themselves during the campaign. They eventually got there thanks to the organizing efforts of women workers and activists, who understood that bettering women’s economic conditions would require a large-scale conceptual realignment about what qualifies as “stimulus” or “infrastructure”—about the very nature of work.

To be a woman is to accept the fate that your life, at some point or another, will revolve around the care of a family member. To be a woman in the United States is to accept that you will either pay monstrous sums for that care or do it yourself—likely, at some expense to your job.

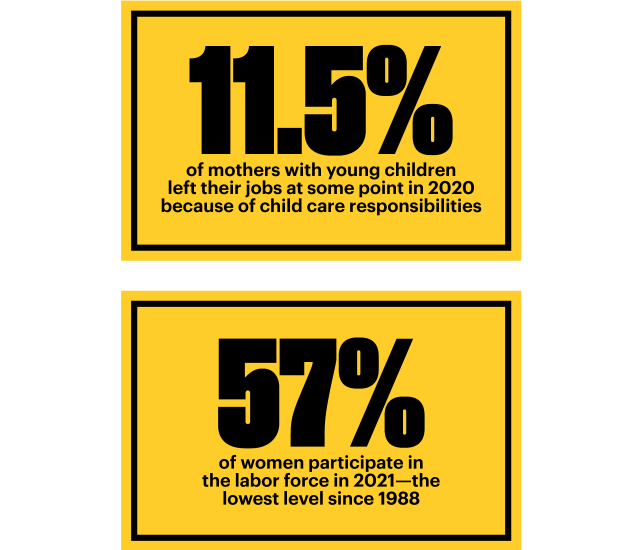

The average cost of full-time infant care in the US is more than $16,000 per year. That’s if it’s even available at all: Nearly half of all Americans live in “child care deserts,” according to a 2018 analysis from the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank. The costs of child care have grown twice as fast as overall inflation since the 1990s, causing an estimated 13 percent decline in employment among mothers with young children. That comes at a personal cost to women, 1.3 million more of whom could enter the workforce and earn a collective $130 billion across their lifetimes if the country adopted a universal child care system, according to a new study from the National Women’s Law Center and Columbia University. It also comes at a macroeconomic one: The US could see a $210.2 billion boost to GDP if child care costs were capped at 10 percent of family income, according to a study from CAP.

A similar dynamic holds among adults caring for elderly and disabled family members. Karen Shen, a Harvard University PhD student in economics, discovered what she calls the “most productive daughter” phenomenon, which suggests that states with weak long-term care programs under Medicaid are highly correlated with adult daughters being forced out of the workforce to care for parents. And that applies only to low-income families. Over half of adults 65 and older will require care that Medicare typically doesn’t cover. That ends up being a massive cost, $266,000 on average, of which more than half is paid out of pocket by those seniors and their families.

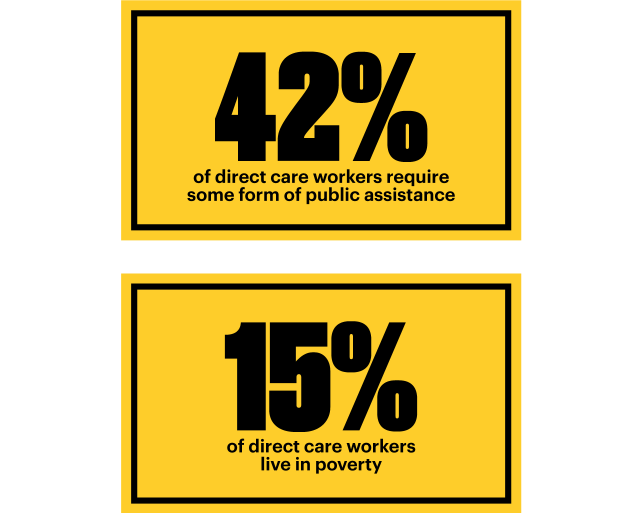

The exorbitant amounts of money spent on any form of caregiving mainly cover the cost of labor, but that still translates to near-poverty wages for care workers. Many of them live like Joyce Barnes, who’s worked as a personal health aide in Richmond, Virginia, for more than three decades. Barnes, who is Black, works 10 hours a day, five or six days a week, preparing meals, washing clothes, and doing housework for a set of clients who can’t care for themselves. She does all this for less than $10 an hour, a wage that forces her to keep her grocery bills limited to just $25 per week—“Oodles of Noodles with tuna fish,” she says—but also puts her just above the threshold to qualify for food stamps. Barnes earns less per hour than her grandson does working at a car wash—as well as her grandson’s girlfriend, who has a pet sitting gig. “You pay someone to take care of your dog $15 an hour,” Barnes says. “but you won’t pay someone to take care of your parents that kind of money?”

Barnes earns just a bit less than the median hourly salary for personal care workers, $11.57 per hour, pay so low it leaves nearly a fifth of those workers living in poverty. The median salary for child care workers is a bit lower at $11.42 per hour, a wage considered livable in only 10 states. Ninety percent of domestic workers are women, and half are women of color.

A resident has his temperature checked at an assisted living facility in Boston.

Craig F. Walker/The Boston Globe/Getty

Stated plainly, the economics go something like this: Women are handing over most or all of their paychecks to other women, who barely earn a living wage, just for the opportunity to enter the workforce—even if the primary purpose of that time in the workforce is to earn money to pay for care. It’s a system that holds women back, financially and professionally, every step of the way.

The pandemic inflicted fresh cruelty on already untenable circumstances. Women bore the brunt of job losses last year—they lost 5.4 million jobs, in all—as nationwide shutdowns brought industries that employ the most women, such as retail and hospitality, to the point of collapse. As of February, nearly 3 million women remained out of the workforce, a product of caregiving responsibilities as much as employment conditions. The loss of income forced families to pull family members from child care centers and nursing homes, many of which shuttered as clients departed. And professional caregivers faced the choice of leaving the workforce to take care of their own families or exposing themselves to the virus in high-risk work settings, often without sick leave.

Right before the pandemic in January 2020, economists had heralded the latest US jobs report showing that women, for the first time since the Great Recession, accounted for more than half of the US workforce. Now, there haven’t been so few working women since the Reagan administration. And while that topline number before COVID painted a rosy picture for working women, the pandemic proved any reading of success “was built on a house of sand,” says Melissa Boteach, the policy director for the National Women’s Law Center. “It was built through the sheer will and determination and innovation of women trying to navigate an economy that wasn’t designed to support them.”

It didn’t have to be this way. The US almost had universal child care in the 1970s when Congress passed a bill with wide bipartisan support, only for President Richard Nixon to veto it, warning that it would favor “communal approaches to child-rearing over against the family-centered approach.” Nixon was doing a bit of red-baiting, but his rationale spoke to what historian Gabriel Winant calls the “porous boundary” between family responsibility and women’s labor. “The care economy historically rose out of and remains contiguous with, in various ways, the institution of marriage and family,” explains Winant, whose book The Next Shift documents how Pittsburgh transformed from a manufacturing economy to a care-centered town. “It was decided that it was closer to the kinds of institutions of servitude or marriage than it was to the factory.”

So when politicians have advanced the need for care work and the rights of the people who do it, their rationale has tended to be grounded in moral or educational terms, not economic ones. Back in the ’90s, Congress passed the Family Medical Leave Act, which grants 12 weeks of unpaid leave to workers so they could care for themselves or ailing family members—an acknowledgment of the need for care, but not its worthiness as work. The Clinton administration also made massive investments in Head Start, a federally funded care and education program for young children living in poverty, couched in terms of childhood development. “When I came into the Senate, women in the workforce were supposed to keep silent about the issues that were challenging for them—whether it was family leave or sick leave or caregiving for parents,” Sen. Patty Murray (D-Wash.), who has served in the Senate since 1992, tells me.

“Caregiving was largely seen as a personal burden,” Poo of the National Domestic Workers Alliance explains. “If you couldn’t figure out how to afford child care or care for your aging parent, it was somehow your personal failure—like you didn’t have enough money or you didn’t save, or you’re a bad parent or a bad daughter.” Nothing was really being done for professional caregivers when Poo began organizing nannies and home care workers in New York City in the late 1990s. “For most of that time, we were really trying to crack the nut of ‘How do these jobs become better jobs?’” Poo tells me. “The work has been devalued, and not even considered real work. We still refer to it as ‘help.’” In 2007, she co-founded the National Domestic Workers Alliance, a network of activist groups that pushed for basic worker protections at the state and local level. Care in Action, an affiliated political group, has also become an organizing powerhouse in Democratic politics—most recently in Georgia, where a legacy of domestic worker organizing was instrumental in flipping both US Senate seats blue. (“We wouldn’t even be having this conversation if it wasn’t for Black women in Georgia,” Boteach says.)

At the same time, the Service Employees International Union waged similar campaigns as it fought state and local governments for the right to organize child care and health care workers and guarantee them basic protections. Last year, SEIU won a 16-year fight in California to provide early childhood educators with collective bargaining rights. “When I first joined our union in the 1980s, the big slogan of the women that were organizing was ‘Invisible No More,’” SEIU President Mary Kay Henry tells me. “I would say our contribution has been to make the provider a part of the conversation and establish that this is work that has value.”

SEIU and its allies took that message to the White House during Obama’s second term and pressed the president to extend overtime and fair wage protections to 2 million home care workers, which he did through executive order. Henry kept the pressure on when Hillary Clinton ran for president in 2016; Ann O’Leary, one of Clinton’s senior policy advisers, recalls that Henry was the first person to refer to the “care economy.” Henry found a like-minded ally in O’Leary, who had done extensive policy research on the lack of federally funded child care, elder care, and paid leave as crucial hurdles for women’s economic parity. Yet when Clinton unveiled a child care proposal that touched on both affordability and workforce concerns, her pollsters discouraged her from overinvesting in the issue. “It didn’t poll well,” O’Leary recalls. “They didn’t think it was going to resonate with people.”

Things weren’t looking much better at the outset of the 2020 Democratic primary. In 2019, Caring Across Generations, a coalition of women- and worker-focused groups, unveiled a proposal for “universal family care.” No 2020 Democratic primary candidates took up the plan, but a few of the Democrats nodded to those aims. Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-Mass.), for example, proposed a universal child care plan premised both on relieving families’ financial burden and raising wages for those who performed that work.

Biden hadn’t been one of those candidates. His labor plan included a push for a $15 minimum wage and strengthened union protections for workers broadly, universal pre-K for 3- and 4-year-olds, and not much else. His campaign had been putting together a child care proposal just as the pandemic shoved the economy over a cliff last March, and Biden and his advisers began to reevaluate those less ambitious goals. The campaign knew its potential biggest weakness against Trump could be that the Republican president had, before the pandemic, overseen a mostly growing economy. So Biden wanted to focus on his vision of rebuilding jobs after the pandemic, which the campaign termed its Build Back Better plan. A large part would be manufacturing, innovation, and a traditional infrastructure package coupled with green investments—a serious, if not emphatic, nod to the Green New Deal.

But there was no way a Democratic presidential candidate’s jobs plan in 2020 could center on a bunch of white men in hard hats. Enter the “care economy,” a $775 billion investment Biden’s campaign envisioned to expand access to child care and long-term care for the elderly and disabled, while also providing millions of good-paying jobs, mainly through the existing Medicare and Child Care and Development Block Grant programs. The idea would give Biden his best chance to hit the massive job creation numbers he sought. And it would be an image boon for the candidate: A 77-year-old white man would put forth a jobs plan with a major emphasis on women—and women of color in particular.

But some aides, many of whom had served with Biden since his Senate or vice presidential days, wanted to put traditional manufacturing and physical infrastructure projects more front and center, unsure of how human-centered projects fit into that vision, according to several sources with knowledge of campaign dynamics. On the care front, they more easily grasped the job potential for child care, since that allowed mothers to head back into the workforce, than for long-term care, a less familiar idea. “How do you talk about it as jobs?” was a commonly asked question.

Biden himself liked the sentiment behind the caregiving proposal when he was first presented with it last spring. It was a matter he could relate to personally. He’d relied on his sister to help raise his two boys after his wife and daughter died in a car accident, and later he needed adult care for his son, Beau, as he received treatment for the brain cancer that eventually killed him. But Biden struggled with how to frame the sales pitch. Voters understood bridges and roads as job-creating projects. They knew child care and elder care as family programs. Infrastructure is from Mars. Care is from Venus.

The challenge would be to collapse the distinction, and recent economic research backed them up. Federal investments in care yielded twice as many jobs as similar investments in infrastructure, according to a 2016 study from the Economic Policy Institute, and it would also free up women to participate in the economy, leading to even greater employment. If the workers were being paid fairly, that would spur a number of “respending” jobs, the sorts of jobs that get created when people have money to spend. This was all the more important given that care is expected to be the fastest-growing segment of the economy over the next decade, according to the Bureau for Labor Statistics. The jobs would be there anyway—they might as well be good. “I was getting to the point where I had to say, ‘Care job creation is vastly superior, but physical infrastructure is still good, also,’” says Josh Bivens, the EPI economist who worked on the study, recalling conversations with colleagues. On the day the campaign launched the caregiving proposal, Bivens, at the behest of Biden advisers, published a blog post asserting the campaign’s plan would, in fact, support 3 million new jobs.

Despite its job-creating possibilities, the campaign generally didn’t call those policies “infrastructure,” and the term appeared just a handful of times in the caregiving platform. As aides developed the Build Back Better agenda, Caring Across Generations circulated a draft of a “care infrastructure” proposal, an update on universal family care for the COVID age, and its development reached Biden’s team. But Biden advisers who worked on the campaign’s caregiving proposal recall that the term “infrastructure” was mentioned but never dominant in their discussions on how to sell the idea.

Advocates kept pushing for more, and the unity task forces between Biden’s campaign and allies of Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) in the aftermath of the primary served as a prime opportunity. “I made a point of talking to every labor person in every task force, and put in my plug for the caregiving economy to get reinforced,” Henry, who served on the health care task force, tells me. “I saw this all as a way to awaken people’s understanding, who don’t normally think of caregiving as part of the nation’s infrastructure.”

Advocates worried that Biden’s commitment might waver once he got to the White House—especially as some congressional Democrats appeared to lose their appetite for ambitious plans after they passed $1.9 trillion in COVID stimulus in March. Amid reports that business interests had been lobbying the administration to drop the caregiving priorities in favor of physical capital projects, activists sent a group of well-respected liberal economists to meet with White House aides to counter the pushback. They argued that caregiving is a public good, and that its reach across society qualified it as infrastructure. “If you’re going for gender equity, racial equity, and worker power, this is about as good as it gets,” says Heidi Shierholz, who served as the Labor Department’s chief economist under Obama and was at that meeting. The $400 billion to expand in-home health care was one of the last line items added to the jobs plan as aides mulled pushing it into the second package that has yet to be released. It was primarily SEIU’s last-minute push that tilted the scales into acting sooner, according to the Washington Post.

Caregiving proponents have a key ally in Congress who will try to hold Biden to his promises. Ever since the Affordable Care Act passed in 2010, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.), a mother of five and grandmother of nine, has privately told Democratic allies on numerous occasions that a federal child care plan is her must-pass social policy agenda item before she retires. On a private call with activists last month, Pelosi insisted that all three pieces of the care economy—child care, long-term care for the elderly and disabled, and paid leave—need to pass together. The White House, meanwhile, has sent the women economists serving in administration on a media tour to emphasize how crucial caregiving is to the ongoing economic recovery. (The White House declined interview requests and requests for comment.)

Caregiving advocates won’t give the White House their seal of approval until after the American Families Plan is revealed. SEIU’s Henry tells me she wants to see the “same set of principles” laid out for long-term care in the jobs plan applied to child care providers, as Biden’s campaign stipulated. No one on Capitol Hill doubts the sincerity of the White House’s overarching aims. Of greater concern are the specifics. Biden’s campaign platform promised to include the 800,000-person waiting list that currently exists for home-based care, a promise that’s absent from the White House proposal. There also aren’t any details on how the money ought to be spent, leaving that to Congress. Whatever route they choose could have enormous implications for precisely how much can be done to improve workers’ wages and alleviate high costs for families. “We need to be able to do the policy that ensures that we have $15 minimum wage, that we have bargaining power for these workers,” Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), who has been behind several caregiving bills, tells me. “Otherwise, we’re not going to be able to get women back into the economy. We’re not going to be able to ensure that these jobs are not just crappy jobs.”

The policies are still extremely popular in polls of voters—even among Republicans. Yet Biden’s commitment to pushing this part of his agenda at all costs remains an open question. “What is their strategy to pass this?” Jayapal adds. “It can’t just be putting it out there and getting everyone’s hopes up.” For the party’s left flank, that means eliminating the Senate filibuster, which remains a nonstarter for moderate Senate Democrats. Instead, the White House has embarked on a circuit of bipartisan meetings, an undertaking that at least gives the impression they’re trying to court lawmakers across the aisle. Caregiving—child care, in particular—has drawn some support from Republican lawmakers over the course of the pandemic, and there’s reason to believe it could be a subject for common ground, albeit with a much more limited scope than what Biden has proposed.

But so far, the GOP has refused to give Biden any wins. The cohort of moderate senators who could theoretically back a Biden caregiving proposal have floated $600–$800 billion as the amount they might approve for all infrastructure. If that persists, much of the money needed for Biden’s proposals to expand access to child care and elder care can pass through the reconciliation process. But thanks to budget rules, reconciliation likely can’t be used to pass the mechanisms to make sure the jobs that are getting funded are, in fact, good ones. Fair wages and worker protections—the pieces nearest and dearest to Biden—require all 60 votes.

The House is hoping to pass a jobs bill by the Fourth of July, and the Senate will take it up sometime thereafter—perhaps for a vote before their August recess, but likely not until after. All the while, shots will go into arms, businesses will open, workers will travel freely on vacations they’ve waited a year and a half to take. Most kids will be back in classrooms next fall. By the end of the year, the unemployment rate is expected to look much less dire.

And when that happens, will anyone remember the crisis? Not the pandemic, but the one that preceded it—the daily struggle of mothers, daughters, sisters, and nieces living in a country that demands they do it all and offers no help in return, and of the caregivers who tend to our most valued family members but are valued less than the workers who walk our dogs. And will there still be a will to use the tools of government to fix the inequities?

“The pandemic has made it visible for this short moment, for this short window,” Boteach of the National Women’s Law Center says. “And while we have this window, we need to not forget what this past year has taught us.”