Last October, the city council in Greensboro, North Carolina, met for a special session. The meeting was held at 7 p.m. over Zoom, and with most of the nine commissioners connecting from their living rooms, it had all the ambiance of an online poker game.

Greensboro, a mill city located an hour west of the university-heavy Research Triangle, helped birth the civil rights movement. In 1960, Black protesters sat down at the lunch counter at the Woolworth’s on Elm Street and refused to leave. The building is now a historic landmark and the home of the International Civil Rights Center and Museum.

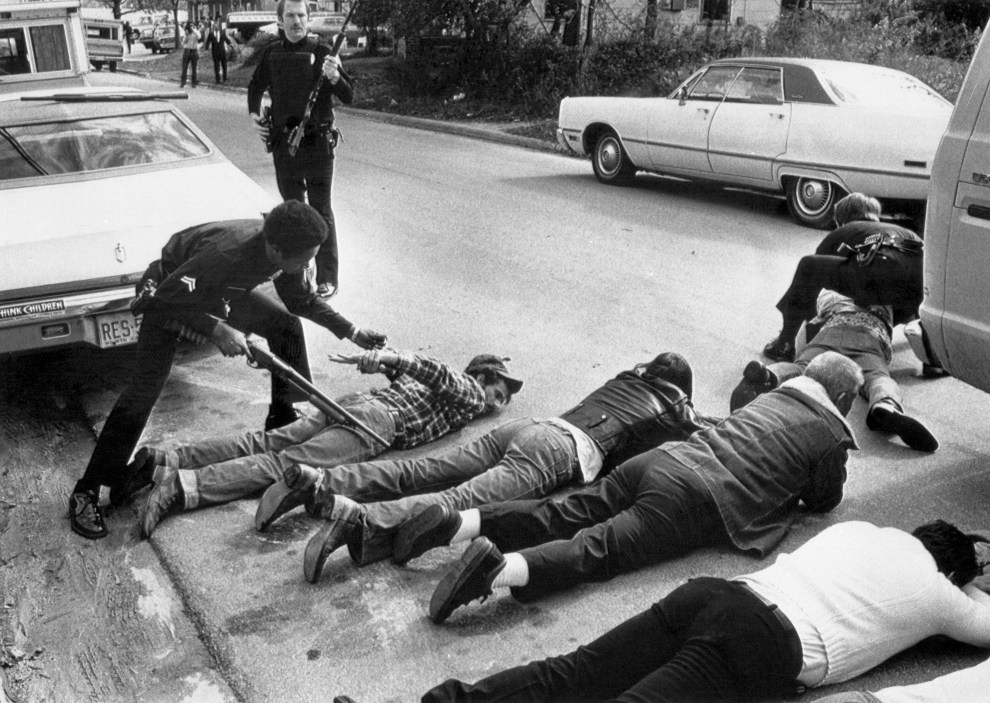

On this autumn night, Greensboro’s city council was going into special session to confront an incident that had clouded that civil rights legacy: the November 3, 1979, killing of five leftists by white supremacists during an anti-Klan protest in a local housing project. Gunned down in the street, four protesters died under a late-morning sun, in front of newspaper photographers and TV news cameras, and before emergency crews could arrive; one perished two days later at a local hospital.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

It was the worst Southern violence in a decade. But the Greensboro Massacre, as it came to be known, quickly disappeared from the front pages of national newspapers. The next day, 52 US hostages were taken in Iran, and America had a larger crisis to worry about—one that birthed, among other things, 24-hour news. Greensboro, however, has been grappling with the massacre ever since. No one was ever convicted. And two criminal trials that ended in acquittals left disturbing questions about whether police steered the communist protesters into a fatal ambush.

Armed police accompany the funeral march for the five protesters killed in the Greensboro Massacre.

Bettmann Archive/Getty

So a sense of unfinished business hung over the city council meeting. The nationwide debate over policing had rekindled those old questions, and a coalition of clergymen was lobbying the council to formally apologize for a delayed police response that left the protesters without protection when the shooting began.

Dr. Goldie Wells, a retired educator, used her few minutes of Zoom time to show an image of a Sankofa bird plucking an egg from its back. Sankofa comes from the language of the Akan peoples of Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire. It means, as one translation has it, “go back to the past and bring forward that which is useful.” “In these times,” Wells said, “there’s so many things we need to apologize for [that] taking this step is long overdue and I think it will mean a lot to a lot of people.”

Support for an apology was not unanimous. One member noted that the council had already expressed “regret,” while another pointed to a broad apology that the city issued just three years earlier. But Greensboro’s mayor, Nancy Vaughan, joined the majority, saying her support was guided by five scholarships, worth $1,979 apiece, that the council was creating for high school graduates to “keep these discussions alive.”

There’s a lot of demand for reckoning in America right now. Cities around the country are debating and in some cases instituting some form of reparations for Black residents. In February, Rep. Barbara Lee (D-Calif.) and Sen. Cory Booker (D-N.J.) reintroduced a bill to establish a United States Commission on Truth, Racial Healing, and Transformation to examine systemic racism; it has 169 co-sponsors. In July, Wesley Morris, Pulitzer Prize–winning critic for the New York Times, called for truth and reconciliation to come to the United States in the form of a “broadcast spectacle,” something that could look “like court, a telethon, therapy, an Oprah show—and more.” On Presidents Day, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi announced plans for a “9/11-type commission” to investigate the January 6 insurrection at the Capitol.

Greensboro’s residents can be forgiven for a sense of déjà vu. Morris might be right that this moment “warrants a depth of conversation the United States has never had.” But Greensboro went down this road in 2004, when the first truth and reconciliation commission in US history was gaveled into existence to reinvestigate the 1979 massacre.

Its mission was to bridge the “deep divides of distrust and skepticism” that it claimed ran through the city. Yet after testimony from more than 100 witnesses, and a 210-page report that exhaustively reconstructed the massacre, the TRC found itself accused of deepening those divides by promoting a vocal minority’s demand for an apology.

The Greensboro commission ran into the problem that bedevils any reconciliation effort, and would surely hover over any national project today: Who gets to decide who apologizes, and for what?

On that Sunday morning in November 1979, about three dozen members of a group called the Communist Workers Party descended on Morningside Homes, a public housing neighborhood of mostly Black mill workers, to stage a “Death to the Klan” march. They brought a flatbed truck with a sound system, an effigy of a Klansman, and plenty of water for what was planned to be a mile-long march. In violation of their parade permit, a few also brought guns.

The CWP was a mishmash of personalities that subscribed to Maoist ideology: Ivy League–educated doctors who spoke in hard-left jargon, Black Power activists, labor organizers. Its leaders had targeted North Carolina, with its anemic rates of union membership and low wages, as a place to recruit a multiracial coalition to their revolutionary movement. There had been an upswing in Klan activity around the state—a klavern in a small town called China Grove had recently drawn protests for trying to screen the racist epic The Birth of a Nation—lending urgency to their organizing efforts. Early that fall, they began planning an anti-Klan march in Greensboro, using incendiary language to coax the KKK out of hiding. One of the leaflets they distributed read “Take a Stand! Smash the Klan!” Another advocated “armed self-defense.”

What the CWP didn’t know was that the KKK had joined forces with a statewide group of neo-Nazis to bolster its ranks. On the morning of the demonstration, an informant called a Greensboro police detective to warn him that two dozen white supremacists were gathering in a nearby house that was awash in guns. At 11:06 a.m., after they’d piled into their cars to head toward Morningside Homes, the cop who’d received the tip began tailing them, radioing his bosses, “It looks like about 30 or 35 people.”

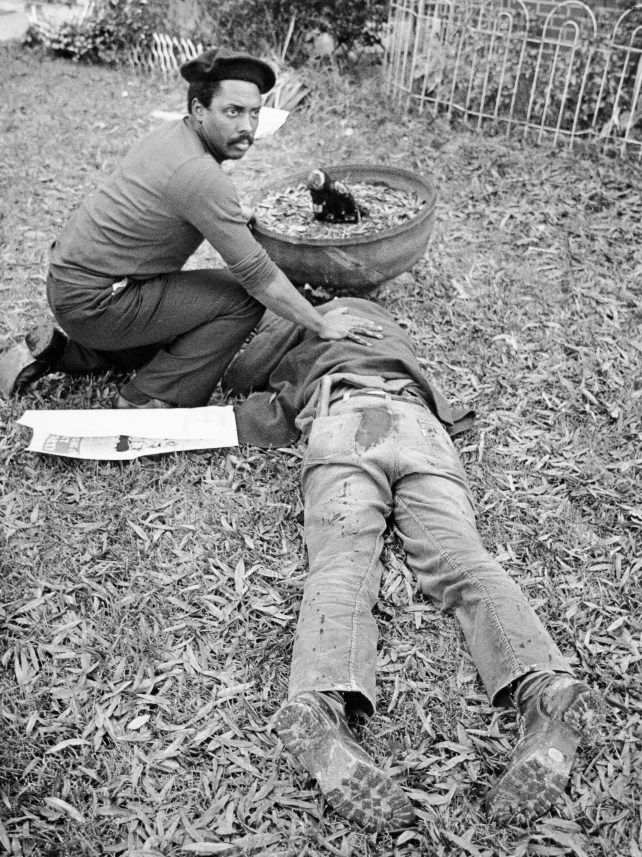

By the time the nine-car caravan rolled up to the housing complex, the streets there were packed with people. But no cops had arrived yet, owing to their belief, according to their later testimony, that the march wasn’t due to start until noon. When a car full of Klansmen swerved in the human crush, a communist protester stuck it with a placard. White supremacists suddenly began pouring out of their cars, shooting into the crowd. One CWP member was hit while crawling on his belly. Another was shot through the back while fighting to keep his gun. Eighty-eight terrible seconds after the melee began, five leftists—César Cauce, Michael Nathan, Bill Sampson, Sandi Smith, and Jim Waller—were critically wounded and a dozen more had been shot.

Nelson Johnson kneels by a victim.

Jim Stratford /News &Record /AP

Many people in Greensboro thought the massacre actually had little to do with the city, since nearly everyone involved came from somewhere else. Indeed, the CWP had repeatedly alienated local organizers whom they’d first approached as allies. “They’d just rag you to death,” one activist told Elizabeth Wheaton, a prominent local journalist. Wheaton noted a pattern: The leftists would urge protesters “toward increasing militancy, leaving more moderate forces no choice but to withdraw,” she wrote. That strategy ran into disaster at Morningside Homes.

The communists, meanwhile, saw the killings as a climax of long-standing racial and class conflicts in the region. They also believed a far-reaching law-enforcement conspiracy had denied them protection from the gunmen. They refused to cooperate with state prosecutors during a 1980 trial, in which an all-white jury acquitted five defendants of murder, and again in a 1984 federal criminal civil rights trial that also ended with acquittals.

Instead, the survivors pursued a civil suit that concluded with a federal jury finding eight people, including two police officers, liable for wrongful death of a single protester. But instead of getting the $48 million they sought, the CWP members settled with the city of Greensboro for just $351,500. While most residents of Greensboro moved on, the survivors spent the next two decades repeating their accusations about a police cover-up in books and speaking tours. It wasn’t until the massacre’s 20th anniversary—which they commemorated with various events and even a play about the episode—that they finally found a way to give their campaign more permanent footing: a truth and reconciliation commission.

For most of the past 500 years, attempts to deal with gross human rights abuses were both rare and ineffective. It’s true that back in 1474, Peter von Hagenbach, a brutal Alsatian knight who commanded territory in the Upper Rhine Valley for the Holy Roman Empire, was overthrown after being accused of murder, rape, and massive theft. In response, Archduke Sigismund of Austria convened a sort of international war crimes tribunal of 28 judges. And the panel, rejecting von Hagenbach’s defense that he was just following orders, had him beheaded for violating “the laws of God and man.” This was the exception, though. Most attempts to address state-sanctioned violence—a conference in the Hague here, a League of Nations committee there—were failures.

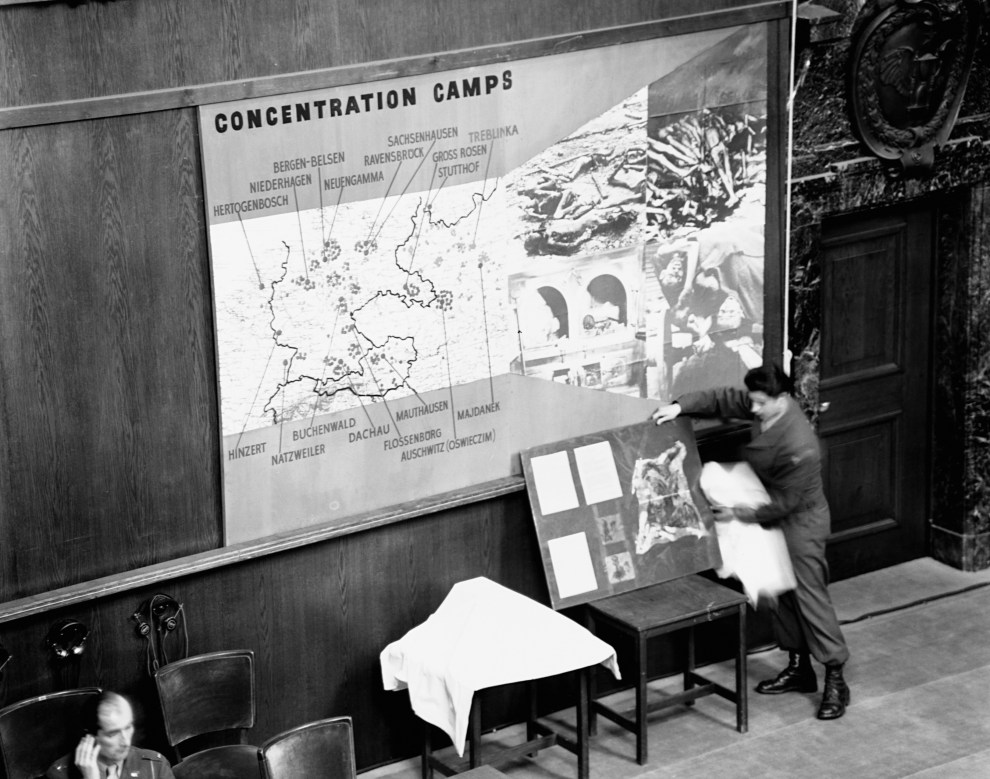

It took the horrors of World War II for the most powerful countries to cooperate in applying international standards to crimes against humanity. The famed Nuremberg Trials, where the United States and its allies put Nazi leaders on trial in 1946, revealed the template: courtroom justice. The offenses the Nuremberg judges examined were enormous, but the basic questions they decided weren’t much different from, say, a case of bank robbery. According to the evidence, who broke what laws? And how should they be punished?

Truth: Evidence regarding concentration camps is presented at the Nuremberg Trials.

Corbis/Getty

Retribution: U.S. military authorities prepare to hang Rudolf Heinrich Suttrop, convicted of transmitting German concentration camp execution orders.

Robert Clover/AP

In the United States, Albert Eglash, a Midwestern psychologist, started to develop an alternative model. In the 1950s, Eglash worked extensively with prisoners, encouraging them to make amends. And he developed a philosophy called “restorative justice,” which posed alternative questions about crime: Who has been hurt? And how can we bring together offenders and victims to acknowledge and repair the damage?

Eventually, Howard Zehr, a Mennonite criminologist who did his own grassroots work helping prisoners in the late ’70s, expanded and popularized Eglash’s ideas. Zehr promoted restorative justice—as opposed to punishment—as a way of making “those who have a stake in a specific offense…address harms, needs, and obligations, in order to heal and put things as right as possible.” Through research, books, and events in more than two dozen countries, Zehr moved the concept from theory into international practice. Restorative justice proved enormously attractive to criminal justice reformers and peacebuilders in both America and Europe, not least because it overlapped with the theology of reconciliation affirmed by many church-based human rights activists who opposed repressive regimes around the globe.

Beginning in the 1980s, as military dictatorships across Latin America fell, the Cold War ended, and conflicts around Africa started burning out, a new generation of leaders turned to investigative inquiries to reckon with past abuses and remake their terrorized societies. In 1990, Chile launched the first national inquest to call itself a commission for “truth and reconciliation.” The country’s newly elected president, Patricio Aylwin, had put an end to 17 years of military rule but was severely limited in what he could do to correct human rights abuses. (For one thing, his predecessor, the brutal Augusto Pinochet, was still commander in chief of the army.) So Aylwin tried to steer a practicable course, promising “the whole truth, and justice insofar as it is possible.” The Chilean commission thoroughly investigated deaths and disappearances, and made it possible for victims to be paid benefits, but did not name specific perpetrators.

“Reparation and prevention were defined as the objectives of the policy,” wrote José Zalaquett, a human rights lawyer and member of the TRC, in the Chilean commission’s report. “Truth and justice would be the primary means to achieve such objectives. The result, it was expected, would be to achieve a reconciliation of the divided Chilean family and a lasting social peace.”

San Salvador, 1980. A student demonstration against El Salvador’s military dictatorship ends in a gunfight, leaving 20 dead.

Michel Philippot/Sygma/Corbis/Getty

El Mozote, El Salvador, 1992. Forensic anthropologist Claudia Bernard brushes dirt from human remains. A postwar truth commission concluded that the army massacred at least 500 people here and in surrounding villages over three days in December 1981.

Michael Stravato/AP

In 1995, after the end of apartheid, South Africa took TRCs to the next level, forming a commission that fully embraced the idea of reconciliation through truth and became an example for the rest of the world. Like the commissions that had come before, the country empowered its TRC to dig into human rights violations, gather testimony, and build a record of the past. Its model, however, included a significant new twist: The TRC also had the power to grant amnesty to anyone who fully disclosed their political crimes.

Politically, the approach was a compromise between Black Africans who wanted their former leaders charged with crimes and apartheid supporters who wanted indemnity. Ideologically, it fulfilled the vision of its chair, the Anglican Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Through his long career, Tutu promoted ubuntu, or humanity through others, and he intended the TRC to be its vehicle. As the South African commission took more than 20,000 statements and held more than two years of televised public hearings, viewers in South Africa and around the globe saw Tutu lead a process, authorized by the legendary Nelson Mandela, that gave voice to formerly powerless citizens and encouraged abusers to personally apologize.

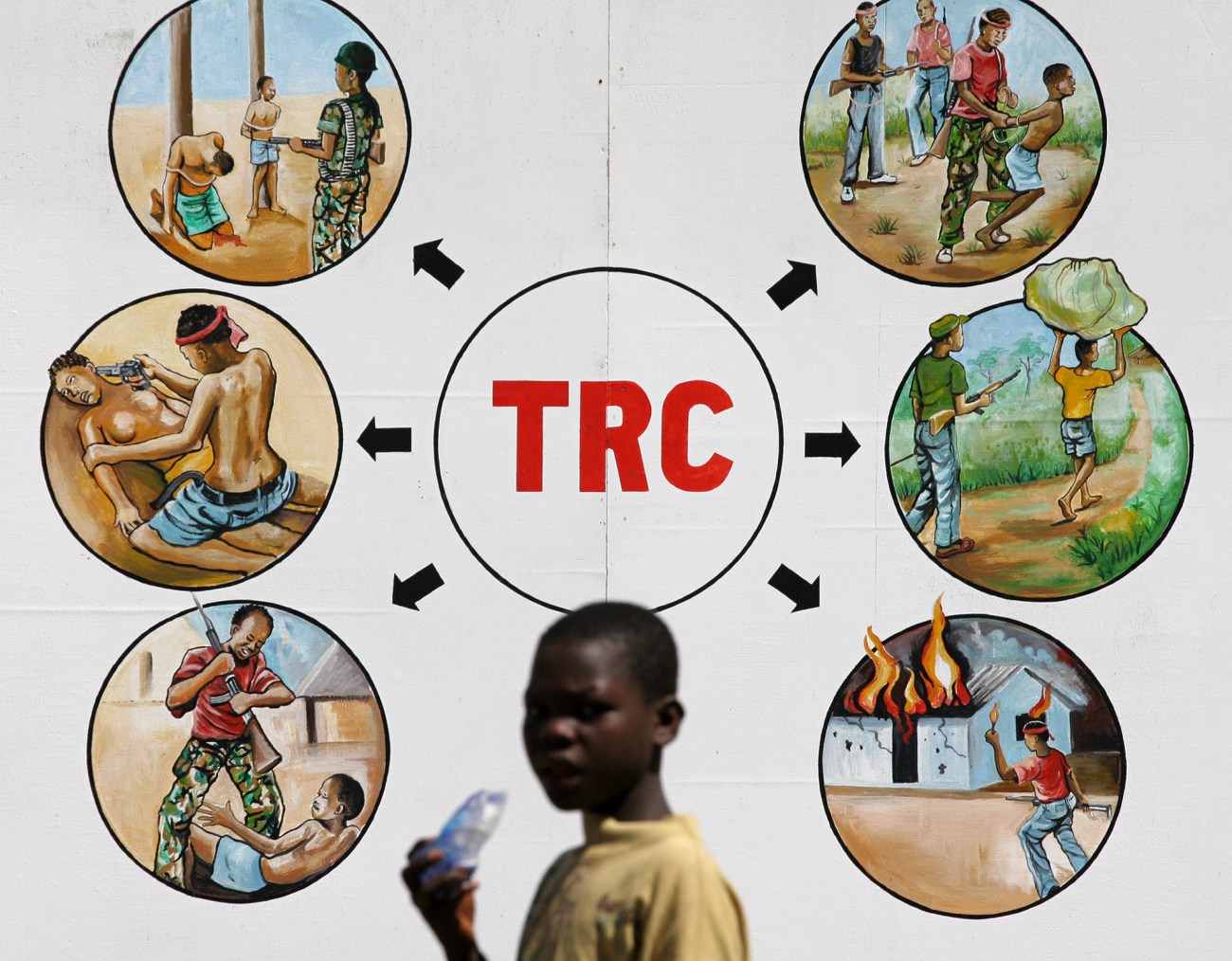

Here, in theory, was a third way, navigating between Nuremberg and amnesty, between tribunal and confessional, neither wholly a court nor solely a healing ceremony: a framework for enemies to meet face to face and repair their relations through the power of personal witness. And it became a prototype for what’s known as “transitional justice.” In the decade after 1996, when the televised TRC hearings began in South Africa, nearly two dozen nations, from Fiji to Nigeria to the former Yugoslavia, established similar commissions.

TRC advocates assumed that commissions could generate enough credible information to change the attitudes and relationships of citizens. Those transformed individuals, in turn, would transform society. In truth, each link in that chain is based on particular views about human nature, and each is open to challenge. Consider ubuntu. “You and I are made for interdependence,” Tutu has said. “You have gifts that I don’t have, I have gifts that you don’t have. And you might almost see God rubbing God’s hands in glee—‘Voila! That is exactly why I created you: that you should know your need for the other.’”

That’s powerful stuff—but not everyone shares that vision, or the particular values behind it. For one thing, as political scientist Michal Ben-Josef Hirsch, a longtime analyst of truth and reconciliation processes, points out, “The idea of a confessional path for liberation, that’s a Christian notion.” Nor does everyone believe that a public organization should impose those values on perpetrators and victim—or that if one does, it will bring about wholesale reconciliation. These are articles of faith.

Duduza township, South Africa, 1985. Boys dance around a car of a suspected police informer.

Gideon Mendel / AFP/Getty

Johannesburg, South Africa, 1997: South African Foreign Minister Pik Botha (right) shakes hands with Archbishop Desmond Tutu at the TRC hearings.

Odd Andersen/AFP/Getty

Or look at how much Zalaquett was assuming in his expectation that truth will achieve reparation and reconciliation. For that conclusion to follow, citizens must agree about whose actions and experiences, whose truth, should be part of a new historical record. They must share a view of what a healed community would look like. And they must have a willingness to move beyond the short-term conflict and pain that uncovering truth often triggers. It may be possible for a TRC to establish or develop such common ground, but it’s hardly inevitable.

As early as 1996, Michael Ignatieff, the Canadian author and politician, expressed doubts about where the whole enterprise would lead. At most, he wrote, TRCs could only “reduce the number of lies that can be circulated unchallenged in public discourse.” But few others debated the question of whether truth inevitably leads to reconciliation. Fewer still considered what might happen when irreconcilable parties can’t bargain their way to an understanding of what’s actually true. And begging those questions meant truth and reconciliation commissions were destined to have problems even when judged on their own terms.

As TRCs became more common, “transitional justice” branched into its own sector of the nonprofit world, supported by foundations, advised by consultants, researched by professors. The field generated more than 1,000 academic articles, books, and book chapters in the 1990s, up from a total of just 150 in the ’70s and ’80s combined. And it powered growth at nonprofits, led by the International Center for Transitional Justice, a New York–based group that launched in 2001. Dedicated to helping communities seek “accountability for past mass atrocity,” the ICTJ quickly became the gold standard in the field, expanding from four full-time employees to more than 40 in 2004, and then to more than 100 in 2006.

But the people and institutions who studied truth and reconciliation were often the same folks advocating for them—like the ICTJ. The inevitable result: Their research reports sloshed together attempts at scholarship, policy proposals, and practical advice. “In the transitional justice literature,” Ben-Josef Hirsch and her colleagues have written, “those who engage in research are often professionally invested in the process they come to evaluate.”

Critically, even as TRCs became standard international practice, there were hardly any ways to measure their effect on the places where they were supposed to bring about change. Even today, the transitional justice establishment is fuzzy about this. The ICTJ is going strong, with affiliates in human rights hotspots from Beirut to Nairobi. According to its most recent financial statements, it took in more than $25 million over the past two years, mostly from European government grants. But its officials are still reluctant to use quantifiable measures to gauge its performance. A report issued by the organization in January states that, while transitional justice groups have developed some metrics to evaluate their work, “information about the actual implementation of these measures is often incomplete or unreliable.”

“These guys pop in, they do seminars and all those kinds of things, everybody says kumbaya, and they pop out,” says James Gibson, a Washington University political scientist and pioneer in measuring the effects of TRCs. “And they go on to the next, without any evidence that it changed anything whatsoever.”

Fernando Travesí, executive director of the ICTJ, disagrees. “Our working methodology is not parachuting into a place, do training, and leave,” he says. “We have a very long engagement in the communities and countries where we work—sometimes for more than 10 years. We look at ourselves as advisers and supporters, not leaders. Maybe that it is why we are called so much: because we really don’t try to be the protagonist of these processes.”

Maybe. But when the concept of a commission alighted in Greensboro in 2003, it wasn’t backed by fully delineated ideas or empirical evidence. It was supported, instead, by a self-validating tangle of advocates, consultants, and academics—a Truth and Reconciliation Complex.

Eight days after the 1979 shootings, the survivors of the Greensboro Massacre held a funeral march to honor their fallen comrades. Reconciliation wasn’t yet on their minds. They advertised the event with leaflets depicting a mill worker in overalls jabbing a rifle’s stock into the jaw of a man helpfully identified as a capitalist, with a Klansman looking on in fear. “AVENGE the MURDER of the CWP 5!” the leaflets read. At the funeral, a CWP leader named Nelson Johnson promised, “The struggle is not over.”

But the members of the CWP soon realized that to keep their struggle alive, they would need new friends, new tools. Their leadership cadre had been slaughtered. And much of their raison d’être seemed to disappear when a citizens’ review commission convinced Greensboro’s elected officials to beef up anti-discrimination laws, add civil rights staff, and increase minority employment. In 1985, amid the stridently anti-communist politics of the Reagan era, the national CWP dissolved.

Greensboro, 1979: Police handcuff suspects in the massacre.

Bettmann Archive/Getty

As the more incendiary aspects of their role began to fade, the survivors created new networks of influence. Johnson threw himself into local organizing campaigns, significantly expanding his footprint in Greensboro by studying theology, becoming a pastor, and co-founding the Beloved Community Center. (“Beloved community” is the name Martin Luther King Jr. gave to his vision of a new order that would issue out of the practice of nonviolence.) Other survivors created the Greensboro Justice Fund out of the civil settlement that the city paid the survivors, and used it to fund local leftist groups.

By the time Johnson and a handful of his old colleagues got the band back together for a series of 20th-anniversary events in Greensboro, they were middle-aged ex-Maoists—writers, professors, clergy—still trying to find their voice in a city that didn’t seem interested in listening. As a former mayor, Jim Melvin, said at the time, “There is virtually no one in Greensboro who wants to relive this tragic event.”

A small and vocal minority, including CWP veterans and also local religious leaders and racial justice advocates, disagreed. Right-wing domestic terrorism had been in resurgent during the Clinton Administration, and Timothy McVeigh had recently been sentenced to death for bombing the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City. The idea of studying the roots of the 1979 massacre resonated with these citizens. As a longtime Greensboro resident named Ed Cone told the Charlotte Observer, “This is an American tragedy. We’ve pushed it away and we need to think about that.”

With an eye toward taking their long-held grievances national, the survivors created a Truth and Community Reconciliation Project and got a New York–based nonprofit, the Andrus Family Fund, to grant it $350,000 on the condition that it hire the ICTJ as consultants—effectively marrying the massacre’s survivors to the Truth and Reconciliation Complex.

Flush with purpose, cash, and advisers, the project’s leaders announced in January 2003 that they were launching a TRC. A selection committee with strong ties to Johnson’s Beloved Community Center then spent a year picking seven commissioners: four women of color, including a representative from an international reconciliation group, a nurse with a long history of activism in Greensboro, a former councilwoman from Durham, and a specialist in teacher education. The fifth woman was a member of the League of Women Voters. A corporate attorney and local religious leader rounded out the panel, which promptly issued a statement of principles vowing to make changes “in the institutions that were consciously or unconsciously complicit in these events.”

Despite the commissioners’ promise that they weren’t interested in “exacting revenge or recrimination,” elected leaders in Greensboro balked. “I’m afraid that any way you slice this, it could be interpreted as a major negative,” said then-Mayor Keith Holliday. “I don’t get the idea that there is a deep wound that needs to have the bandages taken off and be redressed.” Ultimately, the city council voted 6–3 against endorsing the commission’s work. The TRC would have no power to compel testimony or to mandate its recommendations.

Still, from July to August 2005, more than 150 people showed up to three public hearings that were so highly charged they required armed guards. Staffers displayed five white roses to honor the slain communists before each meeting. And witnesses, taking the TRC up on its promise to look into the “context, causes, sequence, and consequences” of the ’79 bloodbath, spoke in deeply personal terms. “I was already going through a lot through the projects, and when I seen that, I just lost all hope,” one former Morningside Homes resident confessed.

Greensboro, 2005: Virgil L. Griffin, imperial wizard of the Cleveland Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, voices his dislike of communism to the TRC during public hearings.

Kim Walker/News&Record/AP

The Reverend Mazie Ferguson lamented how little had changed. “The wounds are still here,” she testified. “The wounds go by the name of homelessness. The wounds go by the name of the unemployed. The wounds are still known by the name of racism.”

Gorrell Pierce, a Carolina Klan leader who had stayed away from Greensboro on November 3, showed up to offer a white-supremacist Greek chorus about the city’s divisions: “[A] lot of people [were] saying, ‘I don’t give a damn about neither side. I wish they’d all killed each other.’”

Mainly, though, the hearings became a way for the CWP survivors to seek public rehabilitation. As Johnson wrote in his prepared testimony:

For nearly twenty-six years, I and others…have had virtually no place to share in depth our views and feelings….We have had to endure an ongoing perversion of context, a constant stream of distortions of the facts as well as demeaning assaults on our motives and characters.

“I was very supportive of the truth and reconciliation process, and still am,” says John Young, a longtime antiwar activist who was one of the earliest local backers of the commission but who felt frozen out as its efforts grew unbalanced. “Sadly, it got a little one-dimensional. At the hearings, I wanted a fuller version of what happened that day [in 1979]. After I began to take a more critical look at the CWP, I was no longer on the inside.”

The commission’s 511-page report, released in May 2006, cast the communists as they had hoped to be portrayed. It placed their protests in the context of the larger civil rights struggle. And it blamed the redbaiting of the group for having “almost entirely obscured the reality of their effort to work for economic and social justice in Greensboro’s disempowered communities.”

The rest of the TRC’s work went into examining the question of police complicity. The report noted, for example, that a federal agent who’d been embedded with the neo-Nazis failed to tell the CWP that an attack was imminent, reinforcing the leftists’ narrative that the feds could have stopped the violence but conspired not to do so.

Greensboro, 2004: Robert Peters signs the commissioners’ pledge of commitment during the swearing-in of five of seven commissioners to the Greensboro TRC.

Kim Walker/News&Record/AP

The panel also highlighted the testimony of Greensboro cops who kept the communists under surveillance for three weeks before the November 3 march but did not pass along a warning from their KKK informant that heavily armed white supremacists were heading toward it that morning. And it characterized an internal GPD report as revealing “a pattern of playing down [the] certainty of information relating to the risks of violence.”

Taken together, the findings pointed to sloppy, even negligent policework. But when it came to the weightier allegation of a conspiracy, two years of work led to this groundbreaking reveal: It depends who you ask.

“We unanimously concur that how one perceives the weight of this evidence is likely to differ with one’s life experience,” the commissioners wrote. “Those whose lived experience is of government institutions failing to protect their interests are understandably more likely to see ‘conspiracy’ while those who have routinely benefited from government protection are more likely to see ‘negligence,’ or even ‘acceptable action.’ We believe this is one reason for the strong divisions in the community in interpreting this event.”

After failing to find the truth on this key point, the commission left Greensboro to grapple with an equally vague recommendation: “Individuals who were responsible for any part of the tragedy of Nov. 3, 1979, should reflect on their role and apologize—publicly and or privately—to those harmed.”

In 2007 and 2008, Jeffrey Sonis, a professor of social medicine at the University of North Carolina, surveyed more than 1,500 residents across Greensboro, chosen randomly, to gauge the TRC’s impact.

The commission and its backers sorely needed some kind of postmortem. After adopting “community reconciliation” as one of its main goals, the Andrus Family Fund had spent nearly $1 million to support the TRC’s work in Greensboro. But throughout the entire tenure of its investment, the fund never had a working definition of that term. Essentially, getting people to come together seemed like good work, so Andrus opened its checkbook—though it did stipulate before-and-after surveys for evaluation. To find out what had been accomplished, the fund sent Sonis into the field.

The survivors believed they had created a model process. Before Sonis had even completed his research, they were publishing articles with titles like “Truth and Reconciliation in Greensboro, North Carolina: A Paradigm for Social Transformation.” But Sonis found that for Greensboro residents overall, the needle hadn’t budged. Sure, some had become more aware of the November 1979 killings. But there were no significant changes when it came to attitudes about reconciliation or social trust. Adds Young, the early supporter, “It surprised us how the commission wasn’t even a blip on the radar for most people.”

Sonis observes: “It’s hard to get buy-in to a process that says, ‘Over time, this may lead to small changes.’ But the reality isn’t that people get up and speak their truth, and then all of a sudden there’s this reconciliation. A TRC isn’t magic.”

That lesson applies even to commissions that transitional justice experts have lauded as models. After its huge initial splash, for example, South Africa’s TRC faced myriad legal and political challenges. The commission’s recommendations never got the full support of the national government, which ultimately paid reparations of about $3,900 apiece to survivors who testified about their experiences, far less than the multiyear program the TRC had proposed. And it suffered plunging support from apartheid victims, who increasingly believed it tilted too far toward amnesty for abusers. The commission helped avert mass violence during the transition to majority rule in South Africa. But its aspirations have also been tarnished by growing income inequality in the years since—a 2018 World Bank study found that the richest 1 percent of the country’s citizens own 71 percent of its wealth—and persistent corruption.

Likewise, Guatemala’s Commission for Historical Clarification concluded in 1999 that 658 massacres had taken place during that country’s 36-year civil war, almost all committed by state-run or paramilitary forces. But Bishop Juan José Gerardi Conedera, who oversaw the effort, was bludgeoned to death two days after the commission issued its findings, and the report led to just four convictions over the following decade. Morocco empaneled an Equity and Reconciliation Commission in 2004, and it investigated more than 20,000 cases of alleged human rights violations and paid out $85 million in reparations. But it didn’t identify any perpetrators by name or even mention King Hassan II, who ruled the nation with an iron fist from 1961 to 1999.

“Many commissions appear to have had little, if any, impact on societal transformations,” Gibson has written. “It would not be terribly surprising to find that truth commissions more often fail than succeed.”

Monrovia, Liberia, 2007: a sign outside the Liberian TRC’s headquarters, illustrating the reasons for the commission’s creation.

Rebecca Blackwell/AP

For Western liberals, TRCs affirm two ideals so powerful as to seem self-evident: The truth shall set you free, and it’s never too late to repent. But again and again, broken societies have shown that bringing enemies together doesn’t guarantee that they will become friends, or partners, or even that they will agree about what’s true. At least not easily, or quickly. In a paradox worthy of Bertrand Russell or Joe Biden, commissions require the kind of consensus whose absence or breakdown impels their creation in the first place.

Having already been dealt a sympathetic hand, the Greensboro survivors kept coming back to the table to pursue reconciliation on their terms. In 2008, the city’s Human Relations Commission, which is dedicated to quality-of-life issues, recommended that officials express “regret” for the way the Death to the Klan march was allowed to get out of control. Marikay Abuzuaiter, who served on that city board, said that when the measure passed the city council by a 5–4 vote, “I thought that was the end of it.”

But the racial violence at the 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, during which a neo-Nazi drove into and killed a counterprotester named Heather Heyer, led to calls for even more contrition. A clergy group named the Pulpit Forum, with Johnson as one of its leaders, insisted on what Abuzuaiter terms “a more substantive apology.” Once again, the city complied. This time, the council voted 7–1 to apologize on behalf of all the city’s agencies to all of Greensboro’s residents. “It was a blanket apology,” says Abuzuaiter, who by then had won election to the council. “It encompassed everyone who was involved that day.”

That wasn’t enough, either. In 2019, the Pulpit Forum began demanding an apology that specifically targeted the police, as opposed to the entire city government. Goldie Wells, the council member who drafted the new apology, believes there was a need to specify that “if the police had been on the scene, that those people would not have lost their lives. There would not have been a massacre.”

Wells did not endorse the allegation by the CWP’s survivors that there had been a police conspiracy. “‘Conspiracy’ is never used in that apology,” she says. “You don’t see it anywhere.” Still, the October vote in favor of her resolution, by a margin of 7–2, was a testament to political perseverance, if not actual reconciliation.

Abuzuaiter, one of the two no votes, says she couldn’t abide the resolution’s finding that only the city and police department were liable. “In all the reports I read, everyone played a part,” she says. “It was an unfortunate part, but everyone played a part, even Nelson Johnson.”

A day after that vote, the reverend appeared on the program Democracy Now! to take what amounted to a victory lap. He insisted Greensboro was still plagued by “an undercurrent of historically accumulated racism built on a bed of falsehood.” But in crediting the coalition he had built for fighting the good fight, he struck a populist chord: “We want to acknowledge the decisions made last night by the city council. We are grateful for that. But we have named it a people’s victory.”

Ultimately, the Greensboro TRC had an unambiguous impact on only one group of people: the massacre survivors who created it in the first place. They used its proceedings to recast their roles in the history of Greensboro’s racial conflict. Over time, their fight to “AVENGE the MURDER of the CWP 5” and “TURN the COUNTRY UPSIDE DOWN” narrowed to the symbolic terrain of a public apology. And that they won. But their long effort also revealed the fundamental flaws baked into the TRC model: the naive if well-intentioned certainty that there’s a straight line running from the accumulation of facts to the emergence of social change, and the danger that advocates will simply echo each other.

Greensboro did show that TRCs can serve two important functions. They can assemble facts. For instance, the commission put together the most comprehensive narrative, sometimes minute by minute, of what happened on November 3, 1979. They can also give voice to citizens who have never before had a public platform, like the residents of Morningside Homes. As Candy Clapp, who was 15 at the time of the massacre, testified, “It was a place where alcohol and illegal drugs were being sold, prostitution.…No child or adult should have been forced to live under these conditions, but people were forced to live there because they were poor.”

Cities around the country are now demonstrating that commissions can also use historical inquiry to set concrete goals for public agencies to redress past wrongs. Last year, for example, a racial equity task force in Durham, North Carolina, an hour away from Greensboro, recommended a series of specific steps to overhaul local policies ranging from criminal justice to health to housing. Around the same time, officials in Evanston, Illinois, developed a plan to use tax revenues from legalized marijuana sales to fund reparations in the form of housing assistance and other initiatives for Black residents.

Greensboro, 2017: The Reverend Nelson Johnson and his wife, Joyce.

Allen G. Breed/AP Photo

What’s missing from these examples? The “R” in TRC. Studying the buried past is itself a herculean task for any commission. Pile on the burden of creating widespread social change and it’s really no wonder most commissions haven’t lived up to their promises. “There are too many people who want to jump straight to reconciliation, ahead of investigation into who did and knew what,” says Emily Harwell, staff director for the Greensboro TRC. “There need to be steps taken to ensure things don’t happen again, and harms inflicted are repaired as best they can be. Any kind of ‘reconciliation’ ahead of those steps is another form of forced forgetting. And then it’s only a matter of time before the zombies from the past return.”

If there’s a productive way forward for TRCs, it’s probably simply as “truth commissions.” Facts can serve as building blocks for awareness, evidence in criminal trials, or talking points in debates about reparations. We can’t know when, if ever, the citizens of Durham or Evanston or Asheville, North Carolina, or Providence, Rhode Island, will undergo the kind of transformation that will remake their communities. But at least they’ll have a better understanding of how the past shapes their present.

“I have become pessimistic about the efficacy of these commissions,” says Gibson. “I think focusing on forgiveness is a real mistake. The best you can hope from reconciliation is for people to be willing to put up with one another and not kill each other.”

Even Jill Williams, the executive director of Greensboro’s TRC, harks back to Ignatieff’s claim that the most truth commissions can do is reduce the lies a society tells itself.

“It might seem kind of pessimistic to say that narrowing lies is the best that can come from a commission,” says Williams, who went on to work for the Andrus Family Fund and then the ICTJ. “But when you see the lies persist, and how much lives are damaged, I think it’s a worthy goal.”

Peter Keating (@PeterKeatingNJ) is an award-winning investigative writer in Montclair, New Jersey.

Shaun Assael (@shaunassael) is an award-winning journalist, author, and producer who covers politics, true crime, and sports…sometimes all at once.