Nurses administer the coronavirus vaccine in Kansas in December 2020. Luke Townsend/ ZUMA

This story was published originally by ProPublica, a nonprofit newsroom that investigates abuses of power. Sign up for ProPublica’s Big Story newsletter to receive stories like this one in your inbox as soon as they are published.

Nurse Kristen Cline was working a 12-hour shift in October at the Royal C. Johnson Veterans Memorial Hospital in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, when a code blue rang through the halls. A patient in an isolation room was dying of a coronavirus that had raged for eight months across the country before it made the state the brightest red dot in a nation of hot spots.

Cline knew she needed to protect herself before entering the room, where a second COVID-19 patient was trembling under the covers, sobbing. She reached for the crinkled and dirty N95 mask she had reused for days.

In her post-death report, Cline described how the patient fell victim to a hospital in chaos. The crash cart and breathing bag that should have been in the room were missing. The patient wasn’t tethered to monitors that could have alerted nurses sooner. He had cried out for help, but the duty nurse was busy with other patients, packed two to a room meant for one.

“He died scared and alone. It didn’t have to be that way. We failed him—not the staff, we did everything we could,” she said. “The system failed him.”

The system also failed her. Since the pandemic’s early weeks, Cline had complained that the Department of Veterans Affairs, which runs the nation’s largest hospital system, wasn’t doing enough to protect its front-line health care workers. She had filed complaints about inadequate personal protective equipment with the agency’s inspector general and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, but they had done nothing. Many months into a pandemic, they were still having to ration masks and being asked to reuse them for as many as five shifts.

From Cline’s perspective and that of other health care workers I spoke with from the VA hospital in Sioux Falls, the lack of masks was a symptom of larger failures at the agency overseeing the medical care of 9 million veterans. The hospitals lacked staff and scrounged to find gowns, medical supplies, ventilators—everything needed to battle COVID-19.

While every American hospital was stretched by the pandemic, the VA’s lack of an effective system for tracking and delivering supplies made it particularly vulnerable, according to a recent examination by the federal Government Accountability Office. When the pandemic hit, the agency relied on a few big contractors to supply everything from N95 masks to needles to isolation gowns. Those few big contractors fell victim to a global shortage of masks. And the VA had no reliable tracking system to tell officials what hospitals have, what they need or what was expired. At the Sioux Falls facility, things got so desperate, the supply chain for masks relied on a guy named Steve who gave them out one at time from a nearby warehouse, employees said.

As COVID-19 overwhelmed the antiquated system, VA leadership asked employees at more than 170 hospitals to enter inventory by hand into spreadsheets every day and did “not have insight” into how resources were being deployed, the report said. In other words, the local Best Buy or Walgreen’s had more efficient ways of managing inventory to get supplies to the right place.

The resulting scramble, which ProPublica has investigated over the past eight months, was a disorganized, poorly overseen effort to buy masks and other supplies from just about anyone who said they could deliver. Hoping to compensate for a disastrous lack of preparation, the VA awarded more than 100 contracts worth over $120 million to vendors with whom it had never done business.

The COVID-19 pandemic came at a tough moment for the agency, which was more than a year into a massive reorganization by the administration of President Donald Trump that left hundreds of jobs empty and sent the VA scrambling to hire contract positions to help with, among other things, procurement of supplies.

Kevin Lyons, an associate professor and supply chain expert at Rutgers Business School, said nothing the VA did before or during the pandemic showed it had a handle on its own purchase and delivery of supplies, let alone prepare for a global shortage. His research is exploring how the Trump administration’s purge of hundreds of VA staff members created a path to disaster.

VA Secretary Robert Wilkie had boasted about across-the-board staff cutbacks in November 2019, just weeks before the first confirmed U.S. COVID-19 case, noting that he had “relieved people as high as network directors to people at the other end of our employee chain.”

Lyons, an Air Force veteran, told me top VA officials have been able to claim all’s well—even as nurses and doctors describe continued shortages and rationing—because bureaucrats who awarded contracts did little or nothing to track how they worked out. He said the rapid-fire approval of contracts gave “the appearance that we’re doing something. But there was no connection between the nurses and the doctors who actually need it.”

“All they really care about is, you know, signing a contract, and then crossing your fingers and hoping that stuff comes,” Lyons said. “And that’s just not the way that supply chain is supposed to happen.”

Wilkie had acknowledged at one point early in the pandemic that COVID-19 had dried up the agency’s supply chain and forced hospitals to ration critical supplies. The agency has acknowledged the need for improvements to its procurement system. But the VA, which has lost more than 90 staff members to COVID-19, denies that it ever left nurses like Cline with inadequate personal protection. “All VA medical centers have adequate capacity, PPE and supplies to meet current demand, and at no point has a VA facility run out of PPE,” said Jamie Maxymuik, a spokeswoman for the VA Sioux Falls health system, in an email.

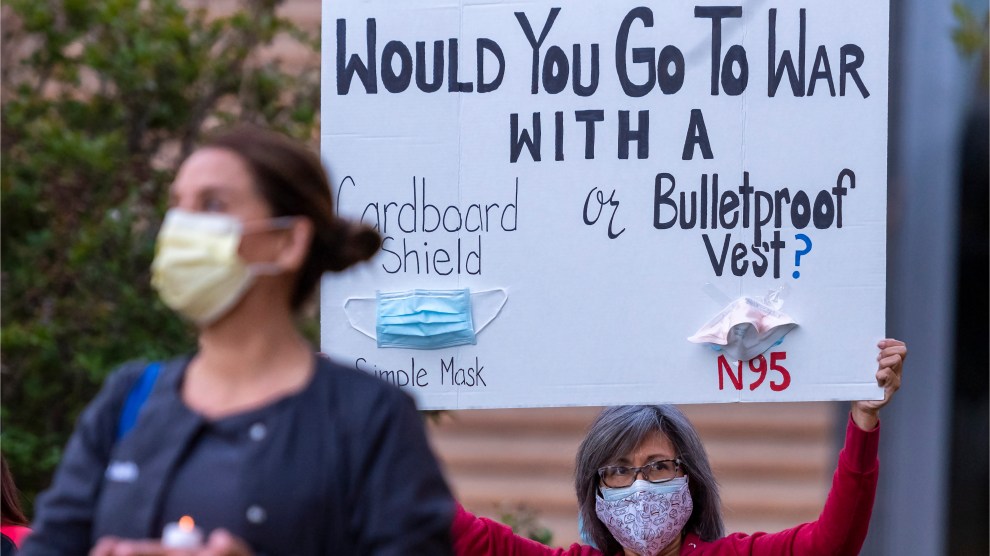

Yet Cline and other hospital workers had felt increasingly vulnerable as the raging virus revealed the government’s failure to adequately prepare or to fight back. In late April and May, emails that Cline shared show the VA instructing nurses to stitch together their own fabric masks at home to get through the crisis. The message coming from managers, Cline said, was to be patriotic and do more with less.

“My first reaction was, ‘Which desk jockey sitting at home came up with this nonsense?’” Cline remembered. “And then I thought, ‘Well, at least they are openly acknowledging that they aren’t providing enough protection.’”

In May, Cline had reached out to me, describing the plight of hospital staff dealing with unresponsive VA management. “They have been rationing masks for weeks now, but sending emails daily saying we have plenty of PPE and that rumors of a shortage are completely false. We have suspected for a few days now that they are lying about this,” Cline, 38, wrote.

Her outrage intensified when she read a story I wrote about how the VA awarded a $34.5 million contract to a random mask broker, who then rented a private jet to locate N95s that never existed from suppliers he didn’t know with money from investors he’d never met.

It was just a glimpse at the chaos disrupting the crucial supply chain on which Cline’s existence depended.

States, cities, hospitals and various federal agencies competed against one another for increasingly scarce masks, many held up in Chinese factories or customs. Health care workers like Cline were captive to the machinations transpiring overhead, unsure why they didn’t have the protection they needed.

In this frenzy, masks typically went to the highest bidder. And out of the woodwork came opportunists, counterfeiters, fakes and well-intentioned but clueless mask brokers trying to make a quick buck.

“The incompetence was just stunning to me,” Cline remembers thinking. “If they had just told us what was going on I would have felt better. But instead they just kept saying we have enough masks.”

Through the summer and fall, as I followed a bizarre trail of mask profiteers, Cline kept me aware of the consequences of an unregulated mask market, a situation that might have been comical if it weren’t so crucial to fighting the spread of COVID-19. Cline did not end up contracting COVID-19 but said the months of chaos and collective failure had left its mark.

“When this is over,” Cline told me. “Those of us who don’t die are going to quit.”

Anatomy of a Disaster

How does one account for the incompetence and greed, the poor planning, and the judgment failures at the government’s highest levels that led us into the worst public health crisis in at least a century?

Even if the Trump administration had empowered civil servants to wrangle supply chain logistics immediately—it didn’t. Even if his administration had dusted off and heeded a pandemic response playbook left behind by the Obama administration—it didn’t. Even if Trump had invoked the Defense Production Act to boost domestic mask manufacturing at the first sign of the crisis—it didn’t. Even if everything had gone right, we were in deep trouble before the first American travelers brought back a mysterious respiratory virus from Wuhan, China, and Europe.

The nation had spent years building up emergency medical supplies in a Strategic National Stockpile that was supposed to help us weather a national crisis. But after long stretches of inactivity and inadequate funding, it turns out it wasn’t all that strategic. Jared Kushner, the president’s senior adviser and son-in-law, made it clear that the federal stockpile was not intended to serve the states, leaving them to fend for themselves in the quest for lifesaving supplies.

Retired Navy Rear Adm. John Polowczyk got plucked from the Defense Department in mid-March to lead the White House’s fledgling Coronavirus Task Force. “I walked in,” he told me, “and the National Stockpile had been given out. I did not have a single—really—I didn’t have a single N95 mask, surgical mask, isolation gown, nitrile glove. It had been issued.”

Polowczyk had spent 30 years mastering the complex logistics of getting supplies from manufacturer to user. But the Trump White House, he said, had “no bench depth” of experts to manage purchasing and distributing vital supplies.

It’s exactly as bad as it sounds, said Robert Handfield, a professor at North Carolina State University who interviewed officials who were working inside the federal effort to supply PPE. He detailed his findings in the Harvard Business Review, but early this month, he boiled it all down for me in a quick summary:

“It was a shit show. They had no idea what was going on.”

The VA embarked on a haphazard buying spree through its procurement system, but by the spring, it had to turn for help from FEMA and draw supplies from the stockpile, a “short-term stop-gap buffer” when critical items are not available, according to the GAO. Along with gloves, gowns, swabs and test kits, the VA received more than 8.2 million respirators, and 2.4 million masks.

Despite dire warnings and lessons learned from the SARS outbreak in 2003 and the H1N1 swine flu in 2009, elected officials and administrations led by both parties simply didn’t prepare for what scientists warned was not just a probability but an eventuality.

A 2010 study commissioned by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention following the swine flu outbreak warned that we needed to stock up on masks or face devastating consequences. The study made sweeping observations about existing and potential breakdowns between the local, state and federal governments.

Today, that report reads like prophecy:

“Delays and conflicts in federal guidance on respiratory protection (N95) led to confusion …” scientists wrote more than a decade ago.

“States experienced significant challenges with the N95 supply chain …”

“There should be a central repository of N95s which is replenished for future events. Federal contracts with N95 and PPE manufacturers generally should be strengthened …”

By February 2020, as the first U.S. outbreaks began, the stockpile housed just 12 million N95 masks, a fraction of what was needed. That same month, Dr. Robert Kadlec, the emergency preparedness czar in the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, told Congress that the country needed 3.5 billion N95 masks, itself probably an underestimate. In other words, the country’s stockpile had less than one half of one percent of the masks we needed.

The stockpile was so depleted, that the moment the spread began, the country needed new production inputs, most of which were in China and would take 60 to 90 days to reach U.S. hospitals by traditional export. If we measure the stockpile in time, the U.S. was several months behind before this even started.

By the time the Trump administration pressured domestic manufacturers to ramp up supply and unleashed $17 billion to source supplies in April, it was far too late.

What that eerily prophetic CDC-commissioned study didn’t predict was the beneficiaries of such chaos, of shortages and desperation, and of exceptionally weak government contracting oversight: mask brokers.

We’re so far into this pandemic now that it’s easy to forget just how absurd the notion of a mask broker truly is. In normal times, masks aren’t all that profitable; an N95 should run about a dollar for anyone working on a dusty home improvement project. They’re a cheap widget in a broad catalog of bigger widgets offered by medical supply giants like 3M, Honeywell and Cardinal Health.

Yet the federal government found itself desperate enough to shell out a fortune to unknown people and companies that hadn’t existed just days before.

The gang brought in to help with PPE and other medical equipment included the inexperienced federal contractor whose private jet ride and failed mask adventure inspired Cline to reach out to me; a former NASCAR driver who allegedly tried to sell a trillion N95 masks that didn’t exist; a wealthy tech investor who used the Task Rabbit contractor-for-hire app to pay people to repackage ineffective Chinese masks so they could pass muster with hospitals.

Just to name a few.

As of December, the federal government spent about $8.5 billion to outfit front-line workers with PPE, medical instruments and various other supplies, according to a ProPublica analysis of spending data. It was not all bad. Some brokers delivered a sorely needed product while making a nice profit. And to be fair to the federal government, many states made the same mistakes.

As brokers made their bets, some making a fortune, some making fools of themselves, others making their criminal defense cases, Cline and millions of other health care workers just prayed there would be enough supplies tomorrow.

“Eye of the Hurricane”

I flew out to meet Cline a few days before Thanksgiving, when South Dakota was reporting the nation’s worst COVID-19 infection numbers and nearing 1 in 700 residents dead. While I had only traveled to the Upper Midwest, it felt as though I’d beamed straight into one of Dr. Anthony Fauci’s nightmares.

“If you want to tell the story of why COVID is so bad in America, I think South Dakota is the perfect microcosm of it all,” Cline told me as we met outdoors for coffee.

Just around the corner from the VA hospital where Cline worked, families huddled maskless and gabbed over heaps of pasta at the local Olive Garden. Gov. Kristi Noem had defied calls from public health experts to issue a state mask mandate, and a local one, recently passed by the Sioux Falls City Council, was, in my observation, scarcely observed.

At my hotel, which was connected by a footbridge to the state’s largest hospital, the nonprofit Sanford Medical Center, young people mingled mask-free in the lobby, shouting gleefully over a case of Bud Lights. Around the corner, the hot tub was bubbling, the first I’d seen since March, and was packed with members of two families. It looked … fun. Like the sort of thing seen in photos coming in lately from Australia, which is averaging zero COVID-19 deaths a day compared with more than 2,000 a day in the U.S.

Cline described a huge disconnect between the devil-may-care attitude of local residents and the reality she was seeing every day. In this alternate universe, she said, there was a “false sense of calm” even as the city moved into the “eye of the hurricane.”

“I had a colleague who went to Sturgis,” Cline said of the August biker rally in South Dakota that may have led to 266,000 new COVID-19 cases. “She said, ‘Well, I drank so much alcohol it probably killed any virus.’ This was a nurse!”

Cline had joined the VA in 2019 after 11 years at Sanford, where her friends kept her posted on their COVID-19 battle. More than 150 COVID-19 patients were filling beds at Sanford, with 27 in the ICU and eight on ventilators, according to state statistics.

Yet the CEO of Sanford, the largest hospital system in the Dakotas, had just days before told thousands of health care workers he’d survived COVID-19 and would not wear a mask because he had “no interest in using masks as a symbolic gesture.” The hospital’s leadership team forced that CEO to retire and sent an email to employees rebutting his comments about masks.

As we sat in the still cold, the city was under silent siege.

Cline and three other VA health care workers I spoke to saw another disconnect between what the VA was saying publicly and conditions on the ground.

“We just had like one surgical face mask for the whole shift,” one VA nurse said, describing a stretch of weeks early in the pandemic when even three-ply blue paper masks were hard to find. “And we were even told to use it for the whole week, which these surgical masks are supposed to just be thrown after single use.”

She said the PPE situation has improved in recent months, but only after the hospital logged 60 COVID-19 deaths. A VA summary of employee deaths shows no medical personnel at the Sioux Falls hospital have died of COVID.

N95 masks, the critical supplies that the CDC recommended for health care workers, were sitting unused in a Sioux Falls warehouse until Cline complained to the VA director. After that, “we magically got fitted for N95s,” this nurse said. “We get it and we stick it in a paper bag, and we use it for five different” shifts.

Such personal accounts were denied by the VA, which signaled to its employees that public comments about hospital conditions would not be tolerated. “In the Spring, Sioux Falls VA Health Care System maintained sufficient PPE for its employees,” the Sioux Falls VA spokeswoman said, noting the agency followed loosened CDC guidelines that allowed for nurses to reuse their masks for several shifts.

The agency was sending mixed messages publicly. Trump had claimed in January that everything was “under control,” but federal contract data showed erratic and desperate purchases with delivery dates for essential hospital purchases that spanned months. Costly supplies sometimes never made it to hospitals, like an order for 5 million masks that in April was diverted by the Federal Emergency Management Agency.

Cline is an outspoken member of the Emergency Nurses Association, an Illinois-based advocacy group, which asked that I point out she’s not speaking on the group’s behalf and offered its own statement:

“When nurses fall ill because of inadequate PPE or other factors in their emergency department, patient care suffers—and that cannot be tolerated. Neither can the ongoing mental stress and burnout … nurses are suffering because of their daily concern for their personal safety,” ENA President Mike Hastings said.

I expressed amazement to Cline that after spending most of a year tracking mask brokers, watching billions in federal dollars spent to get supplies for hospitals like hers, that PPE was still scarce, rationed or nonexistent in many hospital settings. I had traveled into various outbreaks in Chicago, Los Angeles, three cities in Texas, Pittsburgh, Cleveland, New York and New Haven, Connecticut. Yet nearing the end of this most terrible year, the nation was facing its biggest spike in cases and deaths.

Back in Washington the next day, I opened a sobering email from Cline. Her VA shift had stretched to 15 hours so she could watch over a COVID-19 patient in crisis. No one was available to relieve her. He was delirious, so she and another nurse sedated him and tied him down, which kept him alive.

“It’s like this everywhere,” she wrote. “It just got here later. And the shameful thing is we had 8 months to prepare, and we have made a disaster of it.”

“The Bottom Line”

When Cline first said to me, “The bottom line is it was too expensive to protect us,” I thought she was referring specifically to the VA. This didn’t seem right. The VA alone shelled out at least $77.6 million to get PPE, according to our data analysis, so I asked what she meant.

She said she was making a larger point about politics and economics. The depleted stockpile, the brokers and scams, the open bars and sports stadiums, the insistence on ignoring science, the resistance to wearing masks showed the limits of what Americans would sacrifice to protect themselves and each other.

Those of us lucky enough to be spared the sharp hurt of losing a loved one to this virus, or the palpable loss of a job and income, may still be feeling pressed ourselves under the dull weight of this year and what the virus has done to our way of life.

But for Cline, and many health care workers, that nebulous anxiety comes into high definition every time she puts on a used mask to treat someone who got sick because they or someone they cherish didn’t wear theirs.

It was too expensive to beef up the national stockpile. Too expensive to keep mask manufacturing in the U.S. Too expensive to keep bars closed. The personal cost was too high to stay home or sacrifice rugged individualism for an anonymizing face covering.

And yet as Christmas approached, the early results of Sioux Falls’ mask mandate showed that even the simplest effort could pay off. Cases were trending down.

But Cline had been worn out for weeks, and she wanted to spend time with her boyfriend and her daughter. When I relayed that the VA had categorically denied that nurses were being asked to ration PPE, or that there were shortages early on, she said she was done torturing herself.

The day before Christmas Eve, she told her bosses she was quitting and left her keycard with security.

“Being faceless under PPE for nine months,” she said, “has a way of making you feel inconsequential.”