In 2018, Democrats swept every statewide race in Wisconsin, ending nearly a decade of Republican rule. “The voters spoke,” Democrat Tony Evers said after defeating incumbent Gov. Scott Walker. “A change is coming, Wisconsin!”

Not so fast. A month later, the GOP-controlled legislature convened an unprecedented lame-duck session to strip the incoming governor of key administrative and appointment powers and shorten the early voting period to dampen future Democratic turnout. Though their opponents had won more votes, Republicans believed only they were entitled to exercise power. “If you took Madison and Milwaukee out of the state election formula,” Assembly Speaker Robin Vos said of the state’s two largest and most Democratic cities, home to 850,000 people, “we would have a clear majority.”

In fact, they still did. Even though Democrats won 54 percent of votes cast for the state Assembly, Republican control of the last redistricting process in 2011 allowed the GOP to keep almost two-thirds of seats. The legislature set to work nullifying Evers’ agenda. Republicans refused to confirm members of his Cabinet and cut his budget for priorities like health care, schools, and roads. They thwarted his efforts to fight COVID-19, persuading the courts to block his stay-at-home order and his attempt to push back the state’s presidential primary.

For more articles read aloud: download the Audm iPhone app.

Republicans had been preparing for this moment for years. Between gerrymandering and laws designed to reduce the influence of Democratic constituencies—by making it harder to vote, repealing limits on political giving, and stripping unions of collective bargaining rights—they had effectively made Wisconsin “a democracy-free zone,” says Ben Wikler, chair of the Wisconsin Democratic Party. Those efforts helped conservative candidates win a majority on the state Supreme Court, which has upheld nearly every move by the legislature to weaken Evers’ power, creating an almost-impenetrable anti-democracy feedback loop in a state that Joe Biden narrowly won.

“The way that Republican legislators have relentlessly sought to weaponize the courts and torpedo the governing power of Tony Evers is a preview of how Mitch McConnell and Republicans will treat Joe Biden,” says Wikler. “Democrats should prepare accordingly.”

The Wisconsin saga showed how much power Republicans can exert without popular support, and it’s about to be replicated on a much larger scale. The violent invasion of the Capitol on January 6 drew rebukes from many Republican lawmakers. But it reflected, in extreme form, something Republicans have long displayed: a disregard for the will of the majority. With Republicans shut out of the White House and congressional leadership, minority rule is likely to intensify over the next four years in ways not seen in modern times.

Biden won by far the most votes of any candidate in history and beat Donald Trump by one of the largest margins in recent decades. Yet he’ll be handcuffed from the start. Fifty Republican senators will be able to thwart most of his legislative agenda, even though Democratic senators represent 41 million more Americans. The Supreme Court is likely to block many of his executive actions, even though a majority of those justices were appointed by Republican presidents who came to office after losing the popular vote and were confirmed by senators representing a minority of the population. And more than 50 million Americans live in states like Wisconsin, where Republicans control the legislature despite getting fewer votes and will pass another round of gerrymandered maps and new restrictions on voting to entrench minority rule for the next decade.

This isn’t about which party wins elections, but whether democracy itself survives. Some anti-democratic measures were deliberately built into a system that was designed to benefit rich white men: The Senate was created to boost small conservative states and serve as a check on the more democratic House of Representatives, while the Electoral College prevented the direct election of the president and enhanced the power of slave states through the three-fifths clause. But these features have metastasized to a degree the Founding Fathers could have never anticipated, and in ways that threaten the very notion of representative government.

In the past decade, the GOP has dropped any pretense of trying to appeal to a majority of Americans. Instead, recognizing that the structure of America’s political institutions diminishes the influence of urban areas, young Americans, and voters of color, it caters to a conservative white minority that is drastically overrepresented in the Electoral College, the Senate, and gerrymandered legislative districts. This strategy of white grievance reached a fever pitch when domestic terrorists emboldened by the president occupied the Capitol to prevent Congress from certifying Biden’s Electoral College victory. But that unprecedented attempt by Trump and his allies to overturn the election results is a mere prelude to a new era of minority rule, which not only will attempt to block the agenda of a president elected by an overwhelming majority but threatens the long-term health of American democracy. “The will of the people,” wrote Thomas Jefferson in 1801, “is the only legitimate foundation of any government.” And now that foundation is crumbling.

No one has benefited more from minority rule—and done more to ensure it—than Mitch McConnell. For six years, he presided over a Senate majority representing fewer people than the minority party, the longest such stretch in US history, until the January Georgia runoffs gave Democrats a razor-thin majority. Now he’ll do everything he can to obstruct Biden’s popular mandate. Two days after the presidential election, sources close to McConnell told Axios that he would block Biden’s Cabinet appointees if he considered them “radical progressives.” McConnell didn’t even acknowledge Biden’s victory until 42 days after the election, when the Electoral College finalized it.

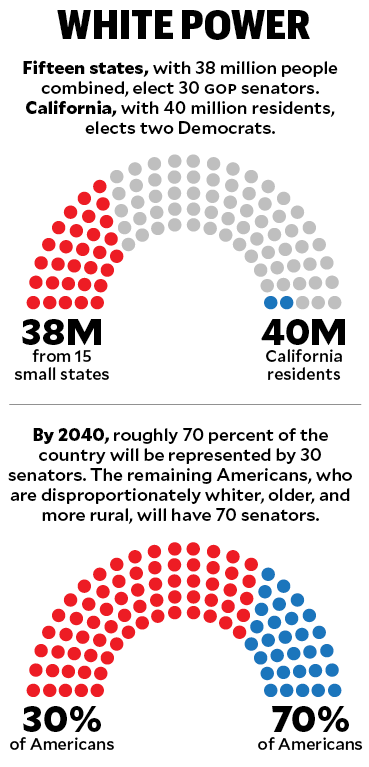

Despite Democrats’ Georgia wins, the GOP’s structural advantage in the Senate is only growing, given its dominance in small rural states. The level of inequality in the Senate today would have shocked the likes of James Madison. In 1790, the country’s most populous state, Virginia, had 12 times as many people as its least populous, Delaware. Today, California has 68 times the population of Wyoming. Fifteen small states with 38 million people combined routinely elect 30 GOP senators; California, with 40 million residents, is represented by two Democrats. This imbalance is getting worse: By 2040, roughly 70 percent of Americans will live in 15 states with 30 senators, while the other 30 percent, who are whiter, older, and more rural than the country as a whole, will elect 70 senators.

Even though Democrats now have the slimmest possible majority in the Senate, McConnell can still block most major pieces of legislation with the filibuster, which was first widely used by Southern segregationists after Reconstruction to stop civil rights laws and which remains a key tool to obstruct popular majorities by requiring 60 votes to pass bills. As a result, GOP senators from 21 small states who represent less than a quarter of the population can thwart bills supported by a clear majority of Americans. After the 2012 Sandy Hook Elementary School shooting, bipartisan legislation requiring background checks for gun sales was supported by 86 percent of Americans but blocked by 46 senators who represented just 38 percent of the country.

“In the 87 years between the end of Reconstruction and 1964, the only bills that were stopped by filibusters were civil rights bills,” writes Adam Jentleson, a former staffer for Harry Reid, in his new book, The Kill Switch: The Rise of the Modern Senate and the Crippling of American Democracy. Unless Democrats get rid of what President Barack Obama has called a “Jim Crow relic,” McConnell can use the filibuster to block legislation that would expand democratic participation and help reverse minority rule, such as bills recently passed by the House to restore the Voting Rights Act and make it easier to vote. (Killing the filibuster would require the approval of every Democrat in the Senate, and Joe Manchin, the West Virginia moderate, has already said he’s against doing so.)

If congressional obstruction forces Biden to use his executive authority to fulfill key campaign promises on issues like immigration and the environment, McConnell can look to the 234 Trump judicial appointments he helped confirm as another check on the president’s agenda. Trump appointed a third of the Supreme Court and a fourth of the federal judiciary, getting through as many appellate judges in four years as Obama did in eight and lining the bench with judges who are overwhelmingly white, male, and extremely conservative.

As a result, Biden will now inherit fewer than 25 judicial openings, a fourth of Trump’s number, and will have little power to put his own stamp on the courts. “A lot of what we’ve done over the last four years will be undone sooner or later by the next election,” McConnell said on the Senate floor in October just before Justice Amy Coney Barrett was confirmed. “They won’t be able to do much about this for a long time to come.”

Conservative-leaning courts, in turn, have reliably supported GOP efforts to make it harder for Democratic constituencies to vote—from gutting the Voting Rights Act to upholding strict voter ID laws and aggressive voter purging—helping Republicans win elections and appoint more judges, with one undemocratic feature of the system augmenting the other. In the runup to the 2020 election, the Supreme Court upheld a law disenfranchising people with past felony convictions in Florida and reversed efforts to make it easier to vote by mail in Alabama, South Carolina, Texas, and Wisconsin. Trump-nominated appellate judges issued 25 opinions on voting matters before the election; 21 of those made it harder to vote by limiting drop boxes for mail voting, requiring witness signatures on mail ballots, or mandating that such ballots had to arrive by Election Day despite postal delays.

“The courts were celebrated this election cycle because they didn’t go along with Trump’s very radical and nonsensical strategy to overturn the election,” says Wendy Weiser of the Brennan Center for Justice. “But the fact that they didn’t stoop that low is overshadowed by all of the ways in which they rolled back voting rights.” GOP-appointed judges opposed Trump’s plot to steal the last election, but they are certain to make it more difficult for Democrats to win future ones.

Democrats failed to flip a single state legislature in November, but the election was still a wake-up call for the GOP in leftward-trending states like Georgia, which went blue in a presidential election for the first time in nearly 30 years. To protect their political future, Republican-led legislatures in these states will redouble their efforts to entrench minority rule.

The first step is redistricting. The maps Republicans drew after winning a wave election in 2010 allowed them to maintain power for an entire decade in nearly every major battleground state. Following the 2020 census, they’ll get to craft the maps again in 20 states where they control the redistricting process, compared to seven for Democrats. (The rest have divided governments or independent redistricting commissions.) As a result, Republicans will draw nearly three times as many US House districts as Democrats will, a disparity that could easily cost Democrats the House in 2022. The maps passed in 2021 will likely be even more extreme than in 2011 because the Supreme Court has said that federal courts cannot review maps drawn for a partisan advantage, and states with a long history of discrimination will no longer have to get federal approval for those maps under the Voting Rights Act.

Gerrymandered legislatures in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin laid the groundwork for Trump’s stolen-election narrative by preventing election officials from counting mail ballots before Election Day, leading to days of uncertainty. Republican legislators are now weaponizing misinformation about voter fraud to build support for new efforts to restrict ballot access. Georgia Republicans are already vowing to pass sweeping restrictions on mail voting, after Black voters and Democrats used it at a much higher rate than white voters and Republicans. As with gerrymandering, Republican-dominated courts are unlikely to block these efforts; some conservative justices, like Brett Kavanaugh and Neil Gorsuch, have embraced a radical doctrine holding that voting rules passed by state legislatures cannot be reversed by federal courts.

This new push to limit voting rights isn’t just anti-majoritarian; it’s explicitly designed to protect white political power. The Trump campaign—backed by a majority of House Republicans who voted to reject the Electoral College results in Arizona and Pennsylvania even after insurrectionists stormed the Capitol—specifically tried to throw out votes in heavily Black cities like Atlanta, Detroit, Milwaukee, and Philadelphia. “Detroit and Philadelphia—known as two of the most corrupt political places anywhere in our country, easily—cannot be responsible for engineering the outcome of a presidential race,” Trump said two days after the election. The GOP long pursued this goal more subtly by attacking laws like the Voting Rights Act through high-minded legal arguments, but Trump and his allies started saying the quiet part out loud. Now Republicans will try to achieve with legislation what they couldn’t with litigation.

Biden will have limited power to counteract the GOP’s embrace of minority rule. There are a few things he can do, however. His Justice Department can enforce the Voting Rights Act and file lawsuits against voting discrimination. He can issue an executive order directing federal agencies to provide voter registration services. He can reverse some of the damage Trump has done to core democratic institutions like the census and postal system.

But his administration cannot pass a new Voting Rights Act or overrule Republican gerrymandering or change the nature of the Senate or the courts on its own. “For all of the same reasons that Trump didn’t have anywhere near the control over the election that he pretended he did, Biden won’t have anywhere near the control over the election that people want him to have,” says Justin Levitt, a former deputy assistant attorney general in the Obama Justice Department.

The only real way to reverse minority rule is through big structural reforms like abolishing the Electoral College, eliminating the filibuster, ending partisan gerrymandering, enshrining a fundamental right to vote in the Constitution, and giving statehood to Washington, DC, and Puerto Rico so as to make the Senate more reflective of the country. But that won’t happen without bipartisan support—and in some cases a constitutional convention. And Republicans have little incentive to adopt these reforms when they can consistently hold power without winning a majority of votes or appealing to a majority of Americans. Until democracy breaks them, they’ll continue to break democracy.