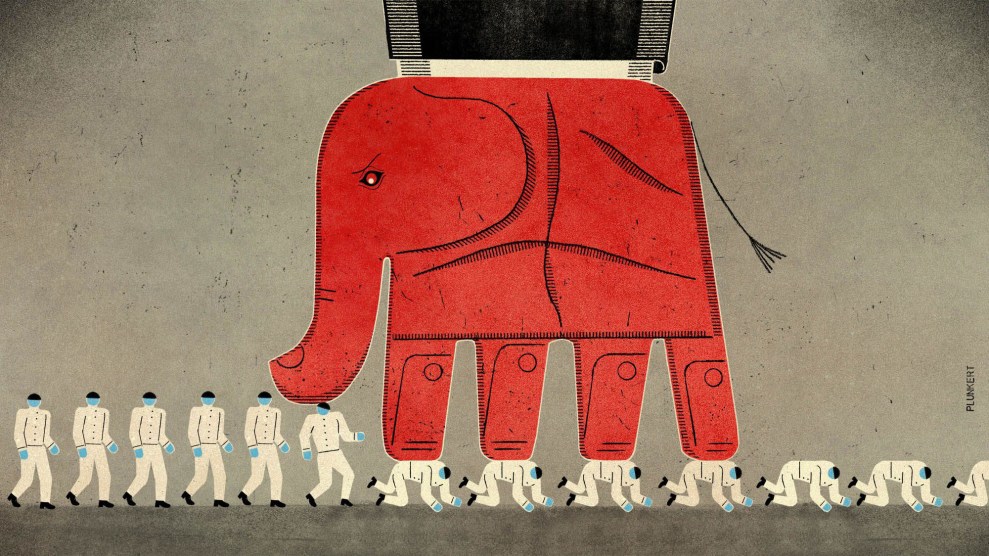

David Plunkert

In 1823, Thomas Jefferson described it as “the most dangerous blot on our Constitution.” In the 1960s, Sen. Estes Kefauver of Tennessee called it “a loaded pistol pointed at our system of government,” whose “continued existence is a game of Russian roulette.” New York Rep. Emanuel Celler once called it “barbarous, unsporting, dangerous, and downright uncivilized.” In 2012, Donald Trump tweeted that the institution is “a disaster for a democracy.” Despite more than 700 legislative efforts to amend or abolish it, the Electoral College remains.

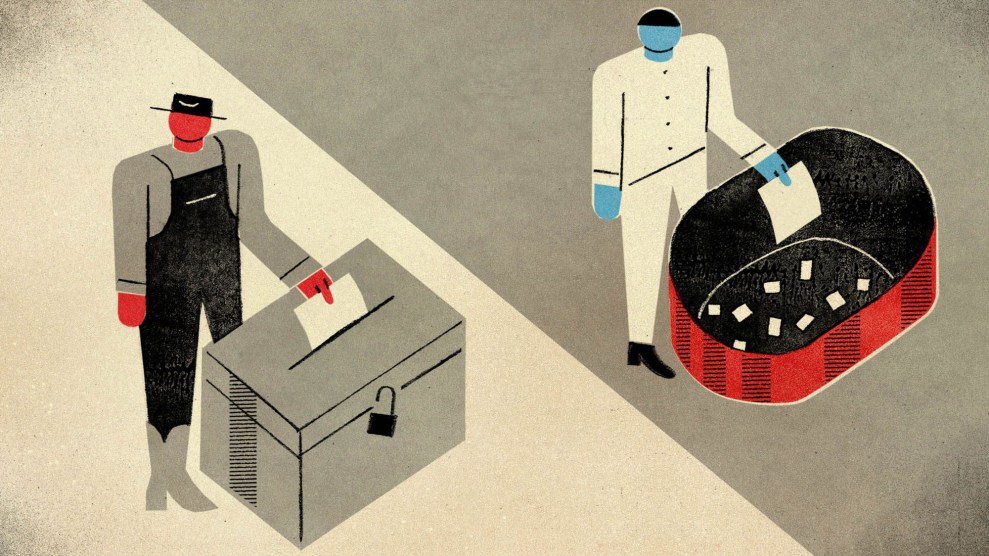

The case against the Electoral College is straightforward: Because states are allocated electors based on the size of their congressional delegations, those with smaller populations have an outsize influence on presidential elections. The result is that a small number of voters in certain battleground states become kingmakers. By one analysis of the 2012 presidential election, four out of five voters had virtually zero influence on the outcome.

“It’s really a relic from the past,” says Wilfred Codrington III, an assistant professor at Brooklyn Law School and a Brennan Center for Justice fellow. The Electoral College was established by the framers of the Constitution as a last-minute deal, a gift to Southern states trying to protect slaveholders’ power and leverage the three-fifths compromise. “It wasn’t a stroke of genius. It was really just the least objectionable at the time,” Codrington says.

The racist origin of the Electoral College reared its ugly head again in 1968, when third-party candidate George Wallace attempted to prevent either Richard Nixon or Hubert Humphrey from securing the 270 electors required to win and then use that leverage to force one of the candidates to oppose federal desegregation measures. Two months later, Sen. Birch Bayh (D-Ind.)—one of the key sponsors of the Equal Rights Amendment and author of an earlier, long-shot bill to replace the Electoral College with a direct popular vote—used the renewed interest in the institution to propose another amendment abolishing it. The effort ultimately died in the Senate, despite overwhelming bipartisan support in the House.

The movement for Electoral College reform gained renewed interest when Trump won in 2016 despite losing the popular vote by nearly 2.9 million. According to a recent opinion poll, 61 percent of Americans favor abolishing the Electoral College. Nearly 90 percent of Democrats supported using a national popular vote to elect the president, but only 23 percent of Republicans agreed (possibly because the GOP has won the popular vote only once since 1990: George W. Bush in 2004). After Trump eked out a win thanks to the Electoral College, he changed his tune on whether it should go.

And the Electoral College played a central role in Trump’s attempts to overturn last year’s election. In December, the state of Texas, on his behalf, claimed that four battleground states—all of which Biden had won—experienced widespread voter fraud, and demanded the US Supreme Court block them from voting in the Electoral College. A last-ditch lawsuit filed by Trump allies sought to grant Vice President Mike Pence the “exclusive authority” to determine which Electoral College votes are counted. Even after a murderous mob of Trump supporters ransacked the Capitol and threatened to hang Pence, more than 100 GOP lawmakers voted against certification of the Electoral College results.

But while Trump and his enablers attempted to use Congress to exploit the Electoral College, proponents of a national popular vote are trying a new strategy to reform it. Rather than amending the Constitution to abolish the Electoral College—which requires two-thirds approval from both the House and the Senate, as well as ratification by at least 38 states—advocates have formed the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact, an agreement between states to award all their electors to whomever wins the popular vote nationally. The compact only goes into effect once it has enough member states to actually decide an election. So far, 15 states plus DC have made the pledge: 74 electoral votes short of the 270 needed. No state with a Republican-controlled legislature has joined.

Opponents question the constitutionality of the compact as a de facto amendment and point to the ease with which states could withdraw their support. President Joe Biden has also indicated that abolishing the Electoral College should only come from a traditional amendment process.

But Trump’s ushering in of an ultraconservative minority-rule presidency, and the threat that he would do it again in 2020, has established Electoral College reform as a serious progressive issue—especially following the Capitol Hill insurrection. “I think the election results make very clear that these gaps between the electoral vote and the popular vote can be very substantial and frequent,” says Alexander Keyssar, a professor of history and social policy at Harvard and author of Why Do We Still Have the Electoral College? “The whole system, as it unfolded on television, looked completely archaic and weird and undemocratic. Even the fact that Trump clung to this deranged hope [of winning]—the very fact that that could be possible after he lost the popular vote by 7 million votes is an indictment of the institution.”

But because Democrats failed to gain the majority in any statehouses, the future of the compact is uncertain. Colorado joined the compact in November. Virginia’s House passed a bill to join the compact in 2020, and the Senate is expected to vote on the measure in the 2021 session. The National Popular Vote organizers are also eyeing eight other states—Arizona, Arkansas, Maine, Michigan, Minnesota, Nevada, North Carolina, and Oklahoma—that have already had one legislative chamber vote in favor of the compact. There are 88 electoral votes up for grabs between those nine states, enough to push the compact into effect.

Codrington thinks Electoral College reform is something everyone—even Republicans—could benefit from. “There are millions of Republicans whose votes are wasted, just as there are millions of Democrats whose votes are wasted, because they live in states that are fully red or fully blue, or mostly red or mostly blue,” he says. “They’re being ignored. And I think that it’s in their interest to think about the popular vote as something that will make their political system more responsive to their interests.”