A cross and makeshift memorial after bones were recovered from a migrant attempting to cross from Mexico into the United States on May 27, 2017, in Arizona.Caitlin O'Hara/Getty Images

The remains of 225 migrants trying to cross the Arizona desert have been found so far in 2020, making it the deadliest year on record. While there’s no one reason for the high number of deaths, they are likely the result of a combination of changes to border policy by the Trump administration, an increase in hostility by US Border Patrol toward humanitarian aid workers, and record-breaking heat in the state.

This is a significant uptick from last year, when 144 remains were found; from 2018, when there were 128; and from 2017, when there were 124, according to data compiled by the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office and Humane Borders, a Tucson-based human rights group. The previous record was in 2010, when 224 remains were found in the Arizona desert.

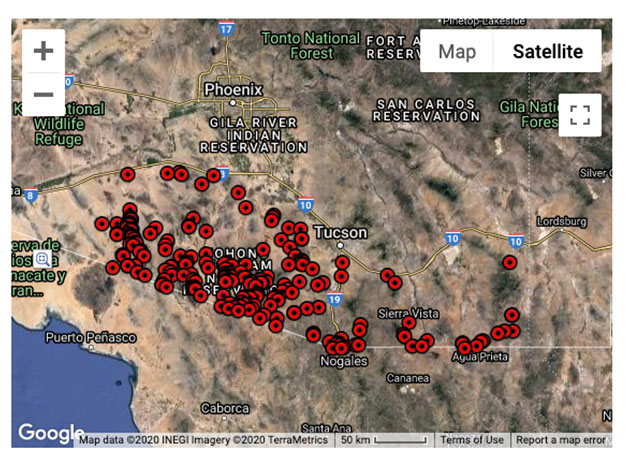

Back in 2013, the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office and Humane Borders first published an online database mapping the deaths of people identified as migrants in Southern Arizona. The public database was set up to help researchers, family members searching for a missing person, and humanitarian aid workers, who could use the information to identify where to leave more water. The map shows a red dot for every body recovered: 3,365 since 2001.

The red dots, even for a single year, can look overwhelming. It’s important to remember each red dot represents someone’s loved one who died trying to reach the United States. Consider just how much red there is in 2020 alone:

Each dot represents the remains of migrants who have been recovered so far in 2020 in Southern Arizona.

OpenGIS Initiative for Deceased Migrants / Humane Borders

According to Greg Hess, chief medical examiner in Pima County, “the heat is likely the biggest contributing factor for the uptick of remains that we are finding.” This year, Arizona broke many records with nonstop extreme heat for months, and with the least amount of rain during the summer.

But the heat alone may not be responsible for the increase. Since March, the Trump administration has used the pandemic to seal shut an already virtually closed US-Mexico border to migrants who turn themselves in to border agents and to asylum seekers. This is forcing more of them to take the dangerous trek through the Arizona desert to avoid apprehension. “They can’t apply for asylum, so their options are considerably cut down and they’re forced into more and more dangerous situations,” says Montana Thames, a humanitarian aid worker with No More Deaths, an advocacy group that seeks to aid migrants crossing in the desert. “Plus, wall construction is happening closer to Nogales and Sasabe, where there are more resources—so because of the wall constitution, they have to go to more dangerous and more remote parts of the desert.”

Robin Reineke, an assistant research social scientist at the University of Arizona Southwest Center, adds, “We have witnessed over the past 20 years, as deaths have increased each time, efforts are made by the US federal government to restrict safe and legal avenues for migration.” She points to the pandemic border closure, as well as the 2019 Remain in Mexico policy, which has kept more than 65,000 asylum seekers stuck in Mexican border towns, as exacerbating the situation.

“When the desert is left as the only option, people will choose it rather than facing the very real dangers of severe poverty and violence if they stay [in their home countries or in Mexican border towns],” says Reineke, who also co-founded the Colibrí Center for Human Rights, which works to identify the remains of migrants. “The rights of migrants and refugees should be respected under international human rights law, not sacrificed in the name of a failed border security spectacle.”

Making matters worse, as part of the changes to border policy since the pandemic started, Border Patrol has been immediately sending people they apprehend in the desert, many of whom are already in bad shape—often dehydrated and disoriented—right back to the border to be released into Mexico. Thames notes this has meant that when they have tried to cross again, they are more vulnerable, already mentally and physically defeated and with fewer resources.

Throughout the years, most of the people who have passed away in the desert have died from exposure to the elements, resulting in hypothermia or hyperthermia. For more than a decade, No More Deaths has been able to help migrants in need, from giving them food and water to providing first aid as they cross the desert. The organization has long had a functioning relationship with Border Patrol, and there was even mutual respect between the two, Thames says. But this year, Thames and other humanitarian aid workers say previous agreements with Border Patrol seemed to go out the window—even as the workers saw people in desperate need of water, food, and medical attention as temperatures reached 120 degrees in the hottest moths. “Everything we do is legal and transparent and we always told Border Patrol what we were doing and where the camps would be,” Thames says.

Over the summer, Border Patrol raided a No More Deaths camp 10 miles north of the border that had been running since 2004. Heavily armed agents then conducted a second raid in the middle of the night just days later. The agents confiscated phones and records of the migrants who had passed through the camp. “They turned their backs on this relationship and upped the violence,” Thames says.

Thames remembers one case this summer when a Border Patrol agent apprehended a person and put them in the back of their truck for almost five hours without allowing aid workers to give the person food or water. “They must’ve had the AC on, because it was 120 degrees out,” she says. “But we had to call the local fire department so they could reason with Border Patrol and allow the person to get food, water, and medical attention.”

Border Patrol did not respond directly to the comments from No More Deaths, but said in an email to Mother Jones that “walking through remote inhospitable terrain is only one of many dangers illegal immigrants face during their dangerous journey into the United States.” The agency, it adds, “has strategically placed rescue beacons in remote locations where individuals in distress can call for help.” (Border Patrol has a specialized unit with EMTs and paramedics to help migrants in distress.)

Crossing the Arizona desert has been dangerous and deadly for decades. Many of people who die while crossing are never even identified; in fact, more than 1,000 of those who have died in the last two decades remain unidentified and the Pima County Medical Examiner’s Office keeps the few items found on each body to try to figure out who the person was. Since 2006, the Colibrí Center for Human Rights has worked to connect thousands of missing persons reports with unidentified remains, and has identified 142 of them. In one small bit of good news from this year, on December 18, Congress passed a bipartisan bill called the Missing Persons and Unidentified Remains Act, which will expand funding to process unidentified remains and help resolve missing persons cases across the country, including at the border. The bill was sent to the president on Monday.

Still, as we head into the new year, Thames warns that the picture of what happened in 2020 could still get worse: “There are many more people who have disappeared, and so many people who haven’t been recovered yet in the desert, so the number could be two or three times what we even know.”