If Nikema Williams knew November 13, 2018, would end the way it did, she says she would’ve worn a different outfit.

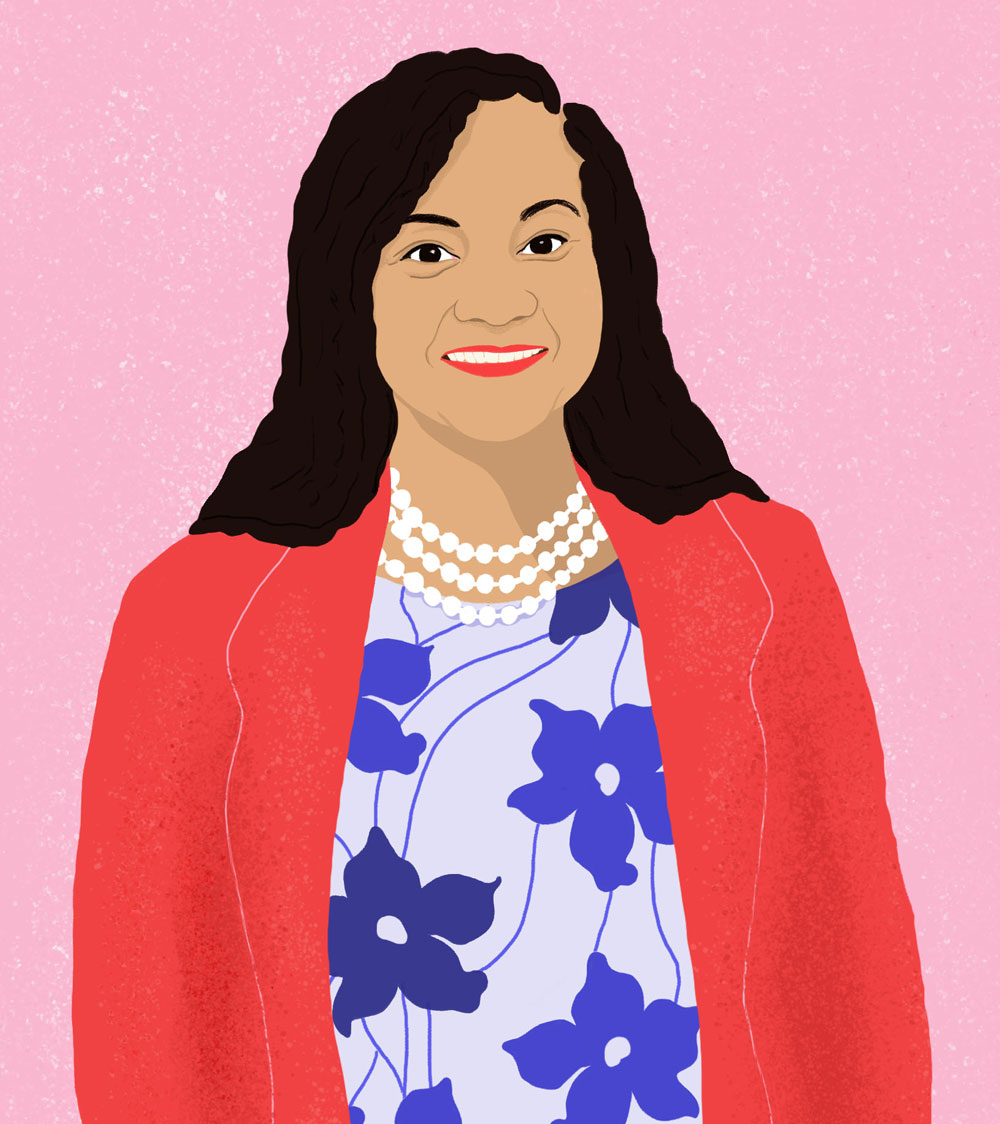

That morning, donning a printed dress, red jacket, heeled boots, and a multistrand pearl set, the Georgia state senator said goodbye to her husband, made plans to pick up their 3-year-old later that afternoon, and headed to the Capitol. It was less than a week after Republican Brian Kemp had declared victory in a hotly contested governor’s race, and Democrat Stacey Abrams was refusing to concede. The legislature was in special session to approve funding for hurricane victims, and by the time the Senate had adjourned, dozens of demonstrators were in the rotunda demanding to “count every vote.”

Unlike her friend and mentor Rep. John Lewis, the storied civil rights leader known for getting arrested more than 40 times, Williams, who represented a diverse swath of Atlanta, hadn’t meant to stir up trouble (good or bad) that day. She was sitting on a third-floor bench with friends, chatting about Thanksgiving plans, when she noticed more police officers roaming around than usual. “I’m like, why are you standing here with zip ties? Never once imagining that in just a few minutes one of these is going to be on me.” She went downstairs to see what the fuss was about. “I noticed one of my constituents standing firmly in her place and not saying a word. And I went and I stood with her… I wanted her to know that she was seen, that I heard her, and I appreciated her being there to raise her voice.”

Before long, Williams recalls, “my hands are being put behind my back.”

Once at the county jail, officers told Williams to lift up her dress so they could search her vaginal cavity. She refused. They made her exchange her boots for a flimsy pair of “little jail shoes.” During the intake process, officers warned Williams that her blood pressure was dangerously high. “You want me to calm down?” Williams remembers thinking. “And they just arrested me for being in the Capitol where I’m a senator?” Each of the protesters faced a misdemeanor charge of disrupting the General Assembly; the charges, including those against Williams, were eventually dropped. (Williams and some of the protesters later sued, claiming the law they were arrested under was nearly identical to one that had been deemed unconstitutional.) The incident signaled a frightening new chapter in Georgia’s long history of voter suppression and put Williams on the national radar.

Afterward, Williams sensed a stark shift in how people reacted to her at the Capitol. White cops, for instance, tended to approach her cautiously, uncertain of how she’d use her new visibility. Black people, particularly building staff, regarded her with respect. When I visited about three months later, I saw a Black janitor pull Williams aside to talk, all familiar, with big smiles and warm hugs. “Thank you for standing up for our people,” she told Williams.

Almost two years later, Williams’ career would take another abrupt turn. Late into a Friday night in July, she was finally going through boxes from a move a year earlier when she got a text message from Jon Ossoff, a friend who had run unsuccessfully for a US House seat in 2017 (and is currently running for US Senate against Republican Sen. David Perdue). Was it true? Ossoff asked. Had John Lewis really died?

That was how Williams found out that the 80-year-old congressman had passed away from pancreatic cancer. Not only had the “conscience of Congress” been a mentor, he’d played an outsize role in her personal life: It was while volunteering for Hillary Clinton’s 2008 presidential campaign that Williams met her husband, Leslie Small, an aide to the lawmaker.

On top of all that, Williams, who has served as chair of the state Democratic Party since early 2019—the first Black woman to do so—notes there was just one business day to inform the secretary of state whether they planned to replace Lewis on the November ballot. Fellow party leaders quickly picked Williams to take his spot, effectively making her the next representative of the heavily Democratic 5th District—a seat Lewis held for more than 30 years.

Lewis’ death was another gut punch in a year filled with them: As the pandemic ripped through Black communities, Williams and three other state senators caught COVID after an infected Republican legislator came to work while awaiting his test results, and as Kemp fought bitterly with Democrats over mask mandates. And after a month of protests in Atlanta over the police killing of Rayshard Brooks, Kemp sent in the National Guard. “It was a very difficult time for us,” Williams says. “I was comforting my grieving husband and trying to figure out what we needed to do as a party to move forward.”

Abrams is most people’s avatar of a Georgia Democrat these days. Williams represents a different path to power—a consistent and strategic march that may not be as compelling as Abrams’ groundbreaking run for governor, but is arguably as effective in helping to transform a state that the national party has often neglected in the last two decades. In November, Joe Biden narrowly won Georgia, and two Democrats, Ossoff and the Reverend Raphael Warnock, are both in runoffs for Senate seats in early January. Regardless of how their races end, this moment is the culmination of years of grassroots work by Abrams, Williams, and a network of progressive organizers and party officials.

I first met Williams in the Before Times, in the winter of 2019. It was somewhat funny to her that her biggest claim to fame until then was the arrest; most of her life, as she tells it, has been the result of methodical planning. Before winning a seat in the state Senate in a special election in 2017, before working as a lobbyist for Planned Parenthood, before attending Talladega College and Jacksonville State University, before pearls became part of her uniform, Williams was a country girl, raised by her grandparents just across the state line in what she calls “the booming metropolis of Smiths Station, Alabama,” population 5,391. She remembers how her grandfather would load her and her cousins in the back of his pickup truck and drive around Lee County to deliver slate cards listing who was running in that year’s elections.

In 2002, she packed up her old Honda Accord and moved to Atlanta, where she juggled three jobs to stay afloat—as an aide to students with disabilities; a salesperson at Banana Republic; and a counselor at a residential group home back in Alabama, to which she commuted every weekend. She came across a book called Who’s Who in Black Atlanta and scrolled through page after page of people who’d “made it,” scouring the organizations and clubs they’d joined. That’s how she found the Young Democrats, which was about to hold a convention in Savannah. “I drove down, and from that point on, I never have not been involved in the Democratic Party,” she says.

Georgia had started to undergo dramatic demographic shifts as the numbers of immigrants and voters of color swelled. But political change was slow going. The Democratic Party’s strategy largely focused on converting disaffected, mostly white, sometimes Republican voters—until Abrams blew up that model, pushing to expand the party’s base by registering and mobilizing new and unlikely voters, often young and of color, instead.

For Williams, Georgia’s 2018 election—and the way victory was stolen from Abrams—was its own political education. Though a study in contrasts, Williams and Abrams are close allies and friends; they have known each other since Abrams was in the statehouse and Williams was lobbying for Planned Parenthood. Now an elected official herself, Williams is also the deputy director of the National Domestic Workers Alliance and the deputy director for Care in Action, the group’s political arm. (Georgia legislators are only in session three months a year.) Care in Action endorsed Abrams in 2018, sent out hundreds of members to canvass for her, and turned its senior advisers, including renowned activists Alicia Garza and Ai-jen Poo, into some of Abrams’ most powerful surrogates. But Kemp, then secretary of state, used his office (which he refused to vacate even as he ran for governor) to launch a specious investigation against Democrats, purge more than 668,000 Georgians from the voter rolls in a single year, hold up registration for 53,000 mostly African American voters, and close hundreds of polling stations. “Death by a thousand paper cuts,” one of Abrams’ colleagues told Mother Jones at the time. That she came so close only to be robbed simply fueled Williams’ resolve to move the party toward something different. “Our turnout was higher than the 2016 election in 2018—voters did their part,” Williams tells me. “The systems failed them. Now we have to change the systems.”

In November 2018, Care in Action joined Abrams and her new voting rights organization, Fair Fight Action, to file a suit against the Georgia state election board, accusing it of gross mismanagement that “deprived citizens, and particularly citizens of color, of their fundamental right to vote,” in violation of the Constitution and the Voting Rights Act. “I remember in 2018 telling people over and over again, there’s a huge voter suppression apparatus,” says Jess Morales Rocketto, executive director of Care in Action, referring to the state’s oppressive “exact match” ID law. “By 2019, we were mounting significant voter education efforts.”

This pivot in strategy marked a subtle but crucial difference: focusing not just on something being taken away, but on expanding the idea of who is included to participate in the first place. And, as Williams learned in the back of her grandfather’s truck, voter turnout means very little if those votes aren’t protected—and won’t happen at all if people don’t know what they’re voting for. Over the past year, Care in Action, along with several other progressive groups, has focused on educating voters about key issues like bail reform and Medicaid, but it has also taught people how to detect misinformation, submit absentee ballots, and act as watchdogs against election interference.

When Abrams endorsed Williams for party chair, she called her “a stalwart for our party, working hard, guiding us through tough times.” The tough times would compound far beyond both their expectations. But now, as Williams heads to Capitol Hill, she is almost serene when reflecting on what it means to fill Lewis’ shoes. “It is my obligation to make sure that I’m not just continuing the things that Congressman Lewis started,” she says, “but that I am creating, charting my own path and creating other opportunities for this country to live up to the promise of America that we all deserve.”