On a steamy Saturday in late June, Joyce McMillan stood outside the Brooklyn Family Court wearing a T-shirt that had “TRUTH OVER TRADITION” emblazoned across the front. A crowd of about 200 people gathered for the first-ever march for Black Families Matter. Compared with the gigantic crowds that had taken over the streets of Brooklyn a few weeks before in the wake of George Floyd’s killing, this group of protesters was small. But the intensity of their rage at what they viewed as a racist and punitive system of justice—this time focused on the Administration for Children’s Services in New York City—was the same. “Stop policing Black families,” one of the signs read. Others charged that “ACS STEALS BLACK BABIES,” “ACS = Police,” and “ACS Destroys Black Families.”

“People tend to think that ACS/CPS supports families, and they don’t,” McMillan told the crowd as participants cheered in agreement. “Any system built to actually protect children should in no way mimic a system that tortures adults!”

McMillan knows what it looks like when ACS steps in to offer “support.” She’s a Black mother, and one day in 1999, an ACS caseworker appeared at her door because someone had alleged that she wasn’t caring for her children properly. Thus began a 20-year struggle, with McMillan defending her parental rights in order to keep her two daughters in her care. Building on her intimate knowledge of ACS’s bureaucracy, hard won through personal experience, McMillan now helps other parents fight the system. From 2016 to 2018, McMillan was the program director for New York City’s Child Welfare Organizing Project (CWOP), a non-profit that was funded by a contract with ACS. In 2018 McMillan left CWOP, and a coalition of parents and social workers, some of whom had once worked for ACS, created the Parent Legislative Action Network to work toward abolishing child protective services’ harmful practices.

“Less than 15 percent of children are in foster care for physical abuse,” says McMillan, citing stats from monthly ACS reports. “When I say we need to abolish ACS, I mean we need to abolish ACS needlessly removing children. We shouldn’t be traumatizing families, children, and communities.”

There are, of course, instances of terrible child abuse, and it’s the mission of ACS and child welfare agencies across the country to intervene. But often the child is not in danger and the caseworker has made a judgment call based only on the way the family is living. “With the vast majority of parents who have children in the foster system, their children are there not because they’ve done something abusive or harmful or abandoned them,” says Emma Ketteringham the managing attorney of the Family Defense Practice at Bronx Defenders, a public defender nonprofit. “They are there because of related stressors to poverty.”

But increasingly, just as with the push to defund the police, parents who have felt unfairly victimized by the agency have mobilized to challenge the system that for years has exercised seemingly unlimited and unaccountable power over the lives of children and their parents. Martin Guggenheim started his law career in the 1971 as a juvenile defense lawyer in New York City. While working in the family court system, he discovered that the parents on trial for child abuse or neglect were lacking legal protections and representation. Parents either didn’t have lawyers or had state-appointed lawyers who were not experts in the family court system. Plus, they lacked major due process protections—the reading of Miranda rights, the trial by jury, the proof of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt, access to a lawyer—that defendants receive in criminal court.

After working in juvenile defense for 19 years, Guggenheim founded the nation’s first Family Defense Clinic at New York University in 1990 in order to train a new generation of ambitious lawyers who would be able to defend parents against child protective services. “For 67 years in the United States, the idea that the state was benign when paying attention to children was sufficient to insulate it from due process protections,” says Guggenheim, still the co-director of the clinic a professor at NYU’s Law School “This is the most important civil rights field that nobody knows about.”

Critics of the child welfare system have argued that child protective services is a carceral institution masquerading as a social service. Parallels can be found in every part of the process. Emergency removals of children from their parents’ homes followed by their placement in foster care without a court order is like pretrial detention. The “petition” that child welfare authorities file against parents is like the charge brought by a police arrest, while the fact-finding hearing before a family court judge is like the trial. Family court resembles a criminal court, complete with judges and ACS attorneys. In New York’s family court system, parents are like defendants, though they are called “respondents.” The intake hearing, where a family court judge decides where the child will stay pending the court’s final decision, is like the bail hearing. The adjudication process, in which the court weighs evidence presented by city authorities against the word of the parents, is comparable to the police testifying against a defendant in criminal court. The disposition is like sentencing. The termination of parental rights? The death penalty.

After McMillan’s speech at front of Brooklyn Family Court, the Black Families Matter protest snaked over the Brooklyn Bridge to Manhattan, where they gathered in Foley Square, on the south side of Triumph of the Human Spirit, a monstrous geometric statue made of black granite. Angeline Montauban, who is Black, was introduced and took the megaphone. The courthouse in which her life had been upended loomed behind her. She pulled down her mask to speak, revealing dimples and a big smile. “This is my son,” she said, pointing to the 8-year-old boy sitting on a low wall in front of the fountain. He was taken away by ACS when he was 2 years old, and for the next five years she fought to get him back.

The Black Families Matter protesters cross the Brooklyn Bridge on June 20, 2020.

Shirin Zarabi

Her ordeal began at 5 a.m. on August 15, 2013. While her partner and their 2-year-old son slept, Montauban retreated to the bathroom with her cellphone. She dialed the number of Safe Horizon, a domestic abuse hotline whose services include counseling and relocation assistance she had seen advertised in subway stations for years. Montauban had just experienced violence at the hands of her partner that made her fear for her life. Trying to stay as quiet as possible, she was looking for help to break a cycle of toxic behavior. Maybe Safe Horizon could refer them to couples therapy or find transitional housing for her and her son as they worked things out.

Crouched in the bathroom, Montauban was glad to have a sympathetic ear as she described physical altercations and violent threats. At one point, Montauban mentioned that she and her partner had a young son. Later Montauban would realize that that’s where the tone shifted. The social worker started asking for some specific information: Montauban’s name, her address, and whether she and her partner lived together. Montauban hung up the phone feeling hyped up despite her lack of sleep and the early hour. After an emotionally exhausting night, she thought she had just taken a step toward making a positive change in her life.

Around noon that same day, a young woman knocked on the door of Montauban’s midtown Manhattan apartment. She introduced herself as Carmen Nelson and explained that she was a caseworker for ACS. The agency had received a report that Montauban’s 2-year-old son had been mistreated. Montauban was bewildered. Despite the difficulties with her partner, she considered them both to be excellent parents. Montauban started to argue before it dawned on her: The social workers at Safe Horizon had reported her call to the New York’s Statewide Central Register of Child Abuse and Maltreatment.

The social workers at Safe Horizon are part of a vast network of mandatory reporters including doctors, nurses, teachers, school administrators, social, therapists, police officers, camp counselors, and nursing home workers. Anyone involved in childcare work is a mandated reporter. But mandated reporters are also present in nearly every venue—from therapists’ offices to homeless shelters to domestic abuse hotlines—where people seek help. They too are all legally required to report any suspicions of child abuse or neglect. From November 2019 to January 2020, just over 70 percent of child abuse calls that ACS received came from mandated reporters.

Nelson told Montauban that she would need to enter her home and look at her son. The caseworker inspected her son’s body—he was healthy and unbruised. She checked out his room, with the plushy stuffed animals in his crib. and made sure there was food in the fridge. The apartment was clean. Montauban asked Nelson why she was there and heard her own story, told confidentially in a moment of crisis, repeated back to her. But there were some notable changes. Nelson said that the report against Montauban’s partner indicated that he abused alcohol and became aggressive when drinking. But Montauban had never said that, nor had she said other things the caseworker told her. (Safe Horizon later confirmed that “alcohol was not mentioned during the client’s interaction,” and ACS retracted this statement in court.) Montauban felt as if she had stepped through the looking glass. She tried to argue, but if anything her defensiveness escalated the tension between them.

The caseworker said that for the next 60 days, twice a month, ACS would be appearing, any time, unannounced, at Montauban’s home for an inspection. Food in the fridge gone bad, a piece of furniture that could be interpreted as a child safety hazard—the slightest abnormality could be grounds for ACS to remove her son and put him into foster care. On September 23, 2013, Montauban got an order of protection for herself against her son’s father, and he moved out. At the New York County Family Court, the attorney representing ACS encouraged Montauban to file a petition for an order of protection for her son against his father as well, but Montauban refused. She told the court that her partner had never harmed their child, and that she believed the presence of his father in her son’s life was important.

On September 27, Montauban’s partner took their son to New York County Family Court for an appointment. Montauban didn’t understand the purpose of the court date and had asked her partner not to go. But, she says, her partner was just trying to follow the rules and do what he could to get their family out of this mess. There’s a daycare on the first floor of the NYC Family Court building. A Family Defense paralegal at Brooklyn Defender Services told me that often, when parents are asked to put a child in the Family Court’s daycare, they “have a ‘Spidey sense’ that that kid won’t come out of that daycare,” he said. ACS has the power to remove a child from his or her parents anywhere. Often it happens at the parents’ home or the child’s school, where the scene can become emotional and tense, sometimes combative. Removing a child who has already been placed in the court’s daycare becomes a conveniently less fraught option.

At around 5:45 p.m., Carmen Nelson called Montauban, who was still at work at a school. ACS had filed a petition requesting that her son be removed from her care for a few reasons: He had allegedly observed domestic violence; Montauban’s partner had neglected the child; and Montauban refused to file an order of protection against her partner that would stop him from seeing his son. While Montauban had originally made the call for help, she felt like no one was doing anything to help her. Instead they were ruining her life. The petition had been approved by a judge, and Montauban’s son was taken from the daycare and put into foster care. He wouldn’t return home that day—or any day over the next five years.

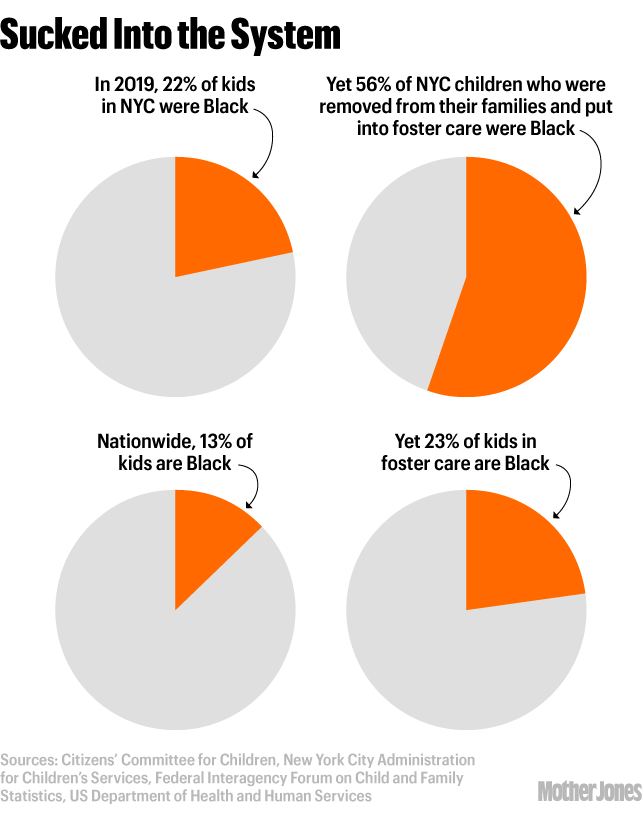

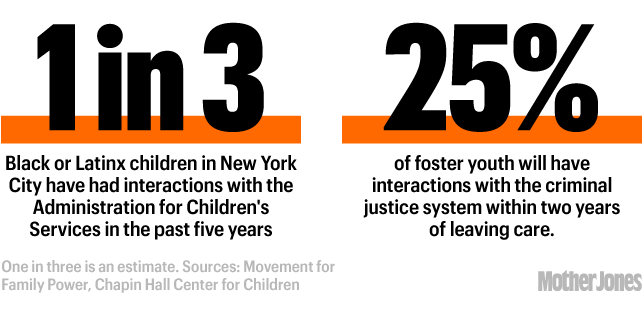

Child protective services is just one strand in the vast and intricate web of institutions and public services that feed in and out of the criminal justice system. If children are separated from their parents and placed into foster case, 25 percent of foster youth will have interactions with the criminal justice system within two years of leaving care. As with the criminal justice system, those who are disproportionately affected are Black, Brown, and poor. Nationwide, according to the most recent statistics from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, nearly a quarter of children in foster care are Black, while Black children make up less than 14 percent of the total population.

In urban centers like New York City, the disparities are even starker. In 2019, 55.5 percent of the 3,485 children who were removed from their families and put into foster care in were Black, and 36.4 percent were Hispanic. Only 5.6 percent were white. An estimated one in three Black or Latinx children have had interactions with ACS in the past five years, involving anything from being stripped and checked for bruises to being moved into foster care. Evidence shows that across the country not only are Black children disproportionately more likely to go into foster care, they also remain in foster care for longer, are less likely to get adopted, and the rights of their parents are more likely to be terminated.

For the parents who find themselves caught up in the child protective services system, one of the scariest parts is their sense of having no control over the outcome, an experience Montauban describes as being in a “labyrinth.” The one place where the parallels to the criminal justice system no longer hold is the due process protections that the Constitution provides to defendants; in family court they simply don’t apply. Caseworkers routinely enter homes without a warrant, and ACS can remove a child from their parents and put them into foster care without a court order. Parents under investigation are not read their Miranda rights. Guilt is determined by preponderance of evidence rather than beyond a reasonable doubt. In most jurisdictions across the country, parents do not have access to lawyers who are experienced in family law. Just under 50 percent of child removals in New York City happen without a court order if an ACS supervisor decides that a child is in imminent danger. This power to remove a child before going to court is what many family defense lawyers consider one of the most egregious violations of parents’ most basic Constitutional protections.

In testimony to the New York City Council, ACS revealed that around 20 to 25 percent of their emergency removals in fiscal year 2018 were reversed once the cases went to court, meaning that something like 400 children were subject to emergency removals who were not in imminent risk of serious harm. Martin Guggenheim considers the high level of emergency removals in New York City “disgusting,” noting that they are completely illegal, though parents have no recourse other than to sue for damages after the fact.

There have been various attempts at reforming the system since Martin Guggenheim first encountered it in 1971. In 1975, the New York legislature codified a state appellate court ruling that parents have the right to a lawyer in a wide range of family court cases. Parents who cannot afford a lawyer are appointed state-subsidized 18-B lawyers, who historically have been underpaid, over-worked, and not experts in family law. In 2002 a report on legal representation in child protective services cases, Jonathan Lippman, New York state’s chief administrative judge, characterized the 18-B crisis in 2002: “There is chaos, there are delays, there are adjournments. Family Court judges are walking the halls looking for people to take cases.”

At around that same time, New York City started contracting with family defense practices that had cropped up throughout the city—Center for Family Representation, for instance, or Bronx Defenders or South Brooklyn Legal Services (now Brooklyn Defender Services)—which had the capacity to take on more clients than the small law clinic that Guggenheim had created at NYU. Still, there aren’t enough specialized family defense lawyers to go around. The New York City Council is now considering a bill that would give parents access to a lawyer from the beginning of an investigation, but the ACS commissioner opposes the measure, speculating that it “could create serious safety issues.”

Government intervention to protect children began in the second half of the 19th century in New York City, when Progressive Era social reformers founded two important institutions that were the precursors of modern-day child protective services. The first was systematized foster care. The second was the creation of a government agency charged with protecting children who were deemed to be in danger or neglected. While cases of child abuse have been recorded in the United States dating back to the 1650s, the first case to capture widespread media attention was in 1874. Mary Ellen was a 10-year-old orphan who lived with and was abused and neglected by foster parents. Her abusive foster mother was prosecuted, and the trial was covered by the New York Times.

The resulting public outcry led to the creation of the first child protective agency in the world, the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children (NYSPCC). The NYSPCC investigated parents accused of abuse, removed children from abusive homes, transported kids from shelters to court dates, and inspected foster homes and centers where infants were kept. A new ethos emerged. Children were not just small adults, but a vulnerable population in need of protection from exploitation. Sometimes this took the form of providing refuge for abused children, but sometimes it also took the form of cash aid to families in need.

With one big exception. Black children were generally omitted from these early child welfare reforms and would continue to be ignored well into the 20th century. In the early 1900s various state legislatures provided “Mother’s Pensions” to single mothers. Black mothers were excluded. Restrictions required that recipients provide “suitable homes” for their children, thereby providing states with a convenient rationale for imposing racial biases on what constituted a “suitable home.” As part of New Deal legislation, the Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC) provided cash payments to needy children through the Social Security Act of 1935. Black children and their families were once again excluded from these assistance programs through restrictive state requirements that deemed Black homes “unsuitable” environments. Black families gained access to welfare services during the welfare rights movement in the 1960s, which explicitly fought to end discriminatory practices in doling out government aid.

At around the same time that activists were fighting to reform welfare, a seismic change occurred that transformed the public perception of child abuse. In 1962, a pediatrician named C. Henry Kempe published a paper identifying a medical condition called “battered child syndrome.” He linked repeated bone fractures and bruises to issues of physical child abuse at home and brought national attention to the plight of abused children. Most significantly, he introduced the radical notion that child abuse was not only a diagnosable medical condition but that it could affect a child of any race, from all social and economic backgrounds. With the child’s rights movement that emerged in the 1970s, child abuse was no longer viewed as being restricted to poor or low-income families.

By 1967, every state had passed laws mandating that adults working in certain professions to report child abuse. In 1974, the Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) was passed by Congress, providing federal funding to states and non-profit organizations to assist in investigating, prosecuting, and preventing child abuse. Amendments to the Social Security Act required states to provide child protective services, and CAPTA authorized federal money to help them do so. At the same time, brutal abuse stories regularly appeared in local and national media, usually with the subplot of how children were failed by the system designed and funded to protect them. In New York, reports of children dying as the result of prolonged abuse led to spikes in investigations by child protective services, even as the agency’s carelessness was often seen as the reason for these tragic deaths.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, any reforms to the child welfare system were undermined by what was described as an epidemic of drug use. News articles reporting on the upsurge in crack usage often focused on children—pejoratively referred to as “crack babies”—being exposed to drugs in utero. Hospital workers started testing mothers and their newborns for evidence of substance use, which then led to a major new source of ACS reports. A 1986 article in The New York Times described a 30 percent rise in ACS reports and quoted an official with the city’s Human Resources Administration who attributed the increase to crack use. The reports tended to be racialized, if not openly racist. Users were portrayed as “urban,” “inner city,” “poor,” members of the “underclass.” In a 1987 New York Times article entitled “Crack Addiction: The Tragic Toll on Women and Their Children,” D. Beny J. Primm, the executive director of the Addiction Research and Treatment Corporation, expressed his worry “about the destruction of the nuclear family among black people, particularly in a population where more than half the families are headed by women. It is such a devastating addiction that these people are willing to abandon food and water and child to take care of their crack habit.”

While the myth of the “crack baby” has been largely debunked, drug testing at birth remains a major source of ACS investigations that largely affect Black mothers. Black women are 10 times as likely to be reported to child protective services for a drug test, and hospitals in low-income areas are much more likely to test for drugs at childbirth than private hospitals in wealthy neighborhoods

In 1997, President Bill Clinton signed a bill that attempted to prioritize permanency in children’s living situations; in effect, it sanctioned the punitive nature of child protective services. As a result of the Adoption and Safe Families Act (ASFA), state governments were encouraged to file for the termination of parental rights if the child had been in foster care for 15 of the most recent 22 months. Since AFSA was passed, over 2 million parents’ rights have been terminated. Adoptions out of the foster system shot up by 70 percent according to a 2004 Congressional report on the law. But many of the children rendered legal orphans by ASFA did not find adoptive homes. They remained in foster care. According to the studies, about 500,000 of them would go on to have interactions with the criminal justice system within two years of leaving foster care.

Just as with other Clinton-era tough-on-crime measures, Black and Brown communities were hit hardest by ASFA. Investigators of child abuse allegations were required to aggressively investigate a family’s entire living situation, including drug use. Once parents came under scrutiny, the likelihood increased that they would be permanently separated from their children, despite research showing the lasting damaging psychological effects of removing children from their parents. “If you look at the impact of ASFA, it’s been responsible for destruction of Black and Brown families,”says Ketteringham from Bronx Defenders. “The system is random, and you lose your children because you fail at child welfare, not because you seriously abused them.”

The vast majority of child maltreatment cases are coded as neglect because of living conditions that are endemic to poverty, such as lack of food, childcare, health insurance, stable housing, and a “failure to thrive.” The overlap between ACS investigations and parents experiencing homelessness is so large that New York City’s four Family Defense clinics all employ housing specialists to liaise with their clients’ homeless shelters. Teyora Graves, who works at the Center for Family Representation in Queens, another major family defense law practice, has found that her clients’ ACS cases further complicate their already-complicated living situations. Parents can lose their space in a family shelter after ACS removes their children, which makes it even more difficult to get their children back. “It’s not something that people with privilege have to deal with,” Graves says.

The woman who appeared at Montauban’s house after the call to Safe Horizon, Carmen Nelson, was one of approximately 1,300 ACS caseworkers who are charged with investigating more than 55,000 families a year in New York City’s five boroughs. ACS is an enormous agency, with a budget of $2.66 billion for the 2021 fiscal year, which is supposed to cover everything from caseworker salaries to stipends for foster parents. But the caseworkers are on the frontlines. To understand the demands of working at ACS, I caught up with Sarah, a former caseworker who prefers that I not use her real name. She immigrated to the United States from the Caribbean, where she was a teacher, and soon received a recruitment email from ACS. She visited the agency’s website and watched videos of caseworkers describing their first cases, finding children covered in marks and bruises. Having already volunteered at nonprofits like the Salvation Army, she was excited at the prospect of getting paid for doing the humanitarian work she loved. (With starting salaries at about $50,000, ACS offers some of the highest-paying jobs for social work in New York City.) She thought she had found her life’s purpose. “Black families, people like myself, needed more assistance,” she says. “I thought I could be of aid to these families.”

During her training she heard one ACS platitude over and over again—“The child is the client.” She learned that poverty is often responsible for child neglect. They were taught the protocol for home visits that Nelson followed when visiting Montauban: First check for marks and bruises on the child, then asses the home for safety and cleanliness, look for a smoke alarm and a carbon monoxide detector. Make sure there is food in the house, supplies for the kids, and running water.

After about five months of training, Sarah was assigned to cover two districts in Brooklyn. In her first report, she used some speculative language about what she had observed at one home. Her supervisor warned her never to be vague or hypothetical because other supervisors at ACS use this as justification for removing children. In another early case, she visited a home where it was alleged that the mom was using marijuana and leaving her child unattended. The mom quickly admitted the drug use, but Sarah saw no evidence that it negatively affected her ability to take care of her child. If she wrote in her report that the mom used marijuana, Sarah’s supervisor explained, it could be reckoned the cause for other issues such as the child being late for school. “I learned very early that I had to tighten what I wrote,” she says, “to make sure that a mother’s word couldn’t be misinterpreted.”

Knowing the potentially dire consequences of her reports, she tried to be especially precise. She listened to parents. She wrote detailed descriptions. She took photographs. Over the course of her two-year stint at ACS, Sarah made over 200 home visits. Of these, only one child was removed. “Other caseworkers were doing removals every day,” she recalls. Was she missing something? She visited many homes where parents were dealing with issues related to poverty, but she didn’t see how poverty had deleterious effects on their love or wish to care for their children. Other caseworkers justified removing children as erring on the side of caution and avoiding high-profile instances of child abuse. “They say they are protecting themselves, which didn’t make sense to me unless you believe that these parents are monsters,” Sarah says. “Poverty doesn’t mean that parents are more savage.”

She suspected that something more insidious was at play. One of the neighborhoods in her district was predominantly white. The other was predominantly Black. Nearly all her cases involved families who lived in the Black district. In her two years, she made only five visits to families with a white parent, and three of those visits were to houses of a mixed-race couple. “Why am I always in the Black community?” she asked her coworkers. One of them told her that the neighborhoods may have gentrified, but she would only ever be visiting Black households. Kurt Mundorff, a legal historian worked for ACS for 14 months in the early 2000s, recounts a similar experience. “I rarely went to the white neighborhoods, but became very familiar with the African American neighborhoods,” he wrote describing his experience in an article for the Cardozo Public Law, Policy, and Ethics Journal.

Once, when Sarah was having trouble finding the parent she was looking for, she saw a white woman standing outside the apartment building. She told the woman that she was with ACS and asked if she knew the elusive parent. “What’s ACS?” the woman asked. Sarah was astonished. “I never met one single Black family that asked me, ‘What’s ACS?’” she said. “There’s one group of people walking around not knowing that ACS exists, and there’s another group of people walking around living in fear of ACS.”

At first, she thought that maybe not many children lived in her white district, but data from the NYC Department of Health revealed that the white neighborhood had 20,000 more children than the Black one. Most of Sarah’s calls came from schools. When Sarah showed up to investigate a case, she would be greeted by a predominantly white panel of school authorities—the teacher, the guidance counselor, the vice principal, the principal. After many interviews, Sarah concluded that in most cases the problem was not with the parents, but the schools. Many of the children that the school authorities were reporting to ACS had some kind of learning disability, like autism. “The autistic children and special needs were most vulnerable to the system,” Sarah says.

Black Lives Matter protesters.

Shirin Zarabi

Sarah’s first supervisor buffered her interaction with the ACS authorities, but after her supervisor quit, things changed. Her subsequent supervisors were more prone to removing children. She saw how interventions discouraged parents from seeking help, making them distrustful of therapists, teachers, and social workers. And dragging parents to court often had a negative effect on their mental health. They became isolated within their communities and had more trouble holding down often precarious employment. Despite the $600 incentive bonus that ACS offered caseworkers after two years, Sarah left right before her two-year work anniversary, becoming one of many who burn out and, bonus or no bonus, quit.

Administrators at ACS are aware of the burnout problem. As of 2018, ACS caseworkers had an average caseload of 10.1 families, though that number crept up to 18.5 families per caseworker in low-income neighborhoods like the South Bronx. In an effort to reverse the attrition trend, ACS set up “Healing Circles” twice a week, where employees can drop in for virtual peer support sessions facilitated by a social worker. Employees also have access to mental health services through the city’s Employee Assistance Program. The financial incentives and added services seem to have made a difference. In 2016, the year before Sarah joined ACS, 38 percent of ACS caseworkers quit after one year and 46 percent quit after two years. In 2018, the one-year attrition rate dropped to 25 percent.

As Sarah reflects on her experience at ACS, she concludes that the racial disparity in the numbers of children who were removed came from a deep-seated assumption that many Black parents are incapable of parenting. Coming from a country where most of the population is Black, Sarah doesn’t get it. “I didn’t grow up here—I guess that’s what made it different for me,” she says. “Most of society is socialized to believe that Black parents are abusive, and teachers are ready to make the report.”

When I reached out to ACS to ask about the alleged racial disparities, a spokesperson wrote in an email that ACS is “committed to addressing the role that racial disproportionality has historically played in the child welfare system” and that they’ve invested in implicit bias training for their staff. The spokesperson also cited the declining number of children in foster care in New York City and attribute it to ACS’s commitment to “keeping children safely at home with their parent through community-based prevention programs.”

After Angeline Montauban’s 2-year-old son was put into foster care, her contact with him was restricted to two hours of supervised visitation on Tuesdays and Thursdays every week at a stranger’s home in the Bronx, which was two train rides and one hour away from Montauban’s apartment. From the ages of 2 to 7 he moved to four different foster homes. His second foster mother wanted to adopt him, and he has vague early memories of being beaten by her. Montauban found an untreated rash all over him during one visit. His fourth foster family said that every night her son asked to go home.

Montauban’s sole focus was granting that wish. She became depressed and had trouble focusing at work. She had always wanted to be a mother and worked diligently to set herself up to be financially stable before having a child at 32 years old. Never once had she imagined a visit from child protective services. “I had a job. I had a college degree. I had 30 credits toward a master’s degree,” she said. She never regretted anything more in her life than making that call to Safe Horizon.

After ACS filed the initial petition that accused Montauban of child maltreatment, the incident of domestic violence that kicked off the investigation quickly faded into the background, and Montauban’s mental health became the central focus. She was required to undergo multiple tests plus two mental health evaluations to demonstrate that she was not psychologically or emotionally impaired. She had to attend parenting classes and domestic violence counseling, weekly appointments with a psychologist, and monthly appointments with a psychiatrist who never prescribed any medication. “They kept telling me to do more and more and more,” she recalls. ACS referred Montauban multiple times to Montego Medical Consulting, a for-profit mental health consulting company that contracted with ACS to perform mental health evaluations, but she refused because she was wary of ACS’s intentions. Montego was later exposed as making millions of dollars off of ACS deals and producing fake mental health reports.

Montauban believes that because she was a “difficult” parent—frequently emailing supervisors, reporting her son’s maltreatment at the hand of his foster parents, participating in a class action lawsuit against ACS, talking to the press—ACS slowed down her case. Plus, the intensity with which she defended herself was then used against her as evidence of emotional instability. This type of retaliation is hard to prove, but family defense lawyers have seen many cases get bogged down in incessant bureaucratic obstacles when parents opposed ACS or questioned the agency’s authority. “There’s a lot of discretion around the positions ACS takes in court,” says Tehra Coles, a litigation supervisor who works with Teyora Graves at the Center for Family Representation. “They have a lot of say over sending a child home, offering favorable settlement, scheduling visits. These can be used to retaliate against a parent that speaks publicly.”

As her case languished in New York County Family Court, Montauban had to take time off of work once or twice a month to go to court appointments—which went nowhere and seemed to accomplish nothing. After ACS submitted the initial petition arguing that her son should be removed from her care—the most significant court appointment, which was the fact-finding hearing, kept getting adjourned. Two of the judges working on her case retired, further slowing down the process.

Montauban was being represented by a state-appointed 18-B lawyer who she says didn’t understand the system and wasn’t able to expedite her case. Montauban found NYU’s Family Defense Clinic on Google and learned that there are lawyers who are experts at defending parents like herself. She tried to get one of the family defense clinics to take her case, but her case had already dragged on for more than two years, and these lawyers are reluctant to take on an open case. “I strongly believe if I had been represented by CFR or one of those other providers, my case could have had a better outcome,” she says. Montauban had regular phone calls with Christine Gottlieb, the co-director of the NYU Family Defense Clinic with Martin Guggenheim. Whenever Montauban had a question about something she’d call Gottlieb, who had knowledge about the workings of the New York family court system that Montauban’s lawyer lacked.

After about 50 court appointments over the two and a half years after her son was taken away, Montauban’s fact-finding hearing was finally scheduled for March 2016. In family court, the fact-finding hearing is when the judge decides, based on a “preponderance of evidence” standard rather than “guilt beyond a reasonable doubt,” whether the parent is guilty of having committed the abuse or neglect that ACS claimed in the petition. Gottlieb explains that parents are extremely vulnerable in this situation because, with the weaker burden of proof and no trial by jury, it’s much more common for judges to reaffirm the ACS decision than to dismiss the ACS claims. “There is deeply systemic feedback that create pressure for judges to rubber stamp family separations,” says Gottlieb. In cases like Montauban’s, her child had already been in foster care for over two years before a judge ever ruled that she was guilty of child maltreatment.

One month before Montauban’s fact-finding hearing, ACS submitted a revised petition to the New York County Family Court. This document no longer claimed, as did the initial petition filed in 2013, that Montauban’s son was being neglected and put in unsafe situations by his father, nor did it mention abuse or neglect. The new petition argued that Montauban was mentally unstable. “When they were asking me for mental health evaluations, it wasn’t to help me,” she says. “It was to build a case.” Joyce McMillan says it’s not unusual for ACS to require parents to get mental health evaluations, then use the results of the evaluations against the parents. “They often say [parents] have mental health issues,” she says. “I see it every day in the programs that I run.”

In March 2016, at the fact-finding hearing, the judge ruled with ACS. Montauban was found guilty.

In November 2017, after another year and a half of court delays, Montauban appeared at the New York County Family Court for the hearing on her parental rights. If the court ruled to terminate her parental rights at this hearing, her son would be put up for adoption. Judge Susan Knipps, 16 years on the bench, ruled that Montauban’s parental rights should be terminated on the basis of a mental health report conducted by the New York County Family Court. According to the judge, the report indicated that Montauban was too mentally unstable to parent her son. In addition, the court claimed that she hadn’t complied with court-ordered services.

The process felt profoundly unfair to Montauban. All the evidence was provided by ACS. The court hadn’t interviewed Montauban’s family, employer, friends, or community to get a sense of what kind of parent she was. She requested a copy of the crucial mental health evaluation that they had conducted in the New York County Family Court’s mental health department, which was located just a few floors away from the court room itself. The judge made her request an additional appointment through a lawyer. When Montauban finally got the 50-page report, she was dumfounded. There was no indication of any mental health issues justifying the removal of her son.

In a Kafkaesque twist that eventually worked to Montauban’s advantage, the court ruled that her parental rights should be terminated because she didn’t complete her required court-ordered services. But Montauban’s dispositional hearing took place one year after the fact-finding hearing and three and a half years after her son had been taken away from her. It was only after she had been found guilty that she could be ordered to do services. Because it had taken so long to have her dispositional hearing, Montauban was found guilty of not doing services that had never been ordered by the court. She fought back and reversed the termination of her parental rights. On August 16, 2018, after fighting a complicated bureaucracy for five years, Montauban was reunited with her 7-year-old son. Finally, he came home.

A growing band of child protective services critics claim that the small reforms have not been enough, and the system is too broken to be repaired. ACS has touted recent numbers showing that over 8,000 children are now in foster care in New York City, down from a whopping 42,000 in 1996, as proof that it’s improved. But a recent report from the Movement for Family Power shows that as the number of children in foster care has decreased since 1996, the number of children under ACS supervision through various service programs increased proportionately, from around 13,000 in 1996 to over 44,000 in 2017. Though fewer children have been separated from their families, ACS’s sphere of influence has not shrunk.

Lisa Sangoi, a former family defense lawyer and the co-founder and co-director of the Movement for Family Power, an advocacy group, points out that the main tools of child protective services are family separation and surveillance. “They retained all the money they were formerly using for the foster system and instead used that to build a very extensive apparatus for family surveillance and control,” she says. With advice from ACS, the courts stipulate what kinds of jobs people keep, what kinds of homes they live in, who lives in the home with the child, drug testing, parenting classes, and anger management classes. Sangoi and her co-founder, Erin Miles Cloud, would like to see government funds go directly into communities and rely on community interventions to keep children safe. “We must envision a world where families are safe not because we have threatened, punished, or policed them, but because we have built up community, prioritized equitable distribution of material resources, and regarded families and neighbors as the first response to trauma,” writes Cloud for the Scholar & Feminist online journal.

Sangoi and Cloud are part of a growing chorus of critics who claim that child protective services do more harm than good. According to Ketteringham, only a small percentage of calls to child protective services across the country are reporting cases of real physical or sexual abuse. A 2004 study showed that 30 percent of children in foster care were removed because their parents did not have stable housing. “The most pressing needs to raise healthy, thriving families are around secure housing, secure employment, nutritional assistance, childcare assistance, and transportation assistance,” says Sangoi. “Those are by and far the deepest needs interim of raising safe, healthy, thriving families.”

Christine Gottlieb, the co-director of NYU’s Family Defense Clinic, has seen how the family court system perpetuates inequalities through structural intransigence and incompetence. “These families are undervalued,” she said. “If you compare the New York Supreme Court, where custody questions related to divorce are handled, versus family court, where poor people’s custody suits are more likely to be handled, it’s just a different world.” The court delays and adjournments and faulty reports that kept Montauban’s son in foster care for five years may have looked different in a legal system that was well funded and running smoothly. It is the same phenomenon of racial inequalities that’s reflected everywhere in the United States, from prisons to schools to healthcare. “You walk into a family court in a diverse area, you see that the system is reserved for Black and Brown families,” says Ketteringham.

The consequences of ACS investigation can follow a parent around for years. Parents with an indicated case of abuse remain in the Statewide Central Register of Child Abuse and Maltreatment until their youngest child is 28 years old, which can affect their employment opportunities. New York Gov. Andrew Cuomo recently signed a bill that would shorten the length of time that a parent’s name will remain in the system. Reforms will go into effect in January 2022.

ACS maintains that they are saving children’s lives. “Our Child Protective Specialists have been our unsung heroes at ACS during this pandemic,” an ACS spokesperson writes me in an email. “They are essential workers who have continued to investigate reports of alleged abuse or neglect and provide support to families across NYC, while leaving their own families and children at home to make sure others are safe.”

For Joyce McMillan, implicit bias training just recycles money back into a multi-billion-dollar system. Instead, she would like to see that money go directly to families to help them get stable housing, access to medical care, and food on the table. McMillan doesn’t even like to call it the child protective services system. She calls it the “family regulation system.” For Montauban it’s the “family destruction system.”

At the Black Families Matter march, Montauban’s 8-year-old son sat behind her, wearing a New York Knicks T-shirt and swinging his legs. At the end of her speech Montauban handed him the megaphone. He took it without hesitation and shouted: “Defund ACS! Defund CPS!” The crowd responded: “Defund ACS! Defund CPS!” After going through the call-and-response a few more times, he handed back the megaphone, smiling shyly. He had dimples just like his mom.

Correction: The original version of this story misstated the action of the judge during the disposition. A dispositional hearing occurs after a judge has found neglect or abuse.