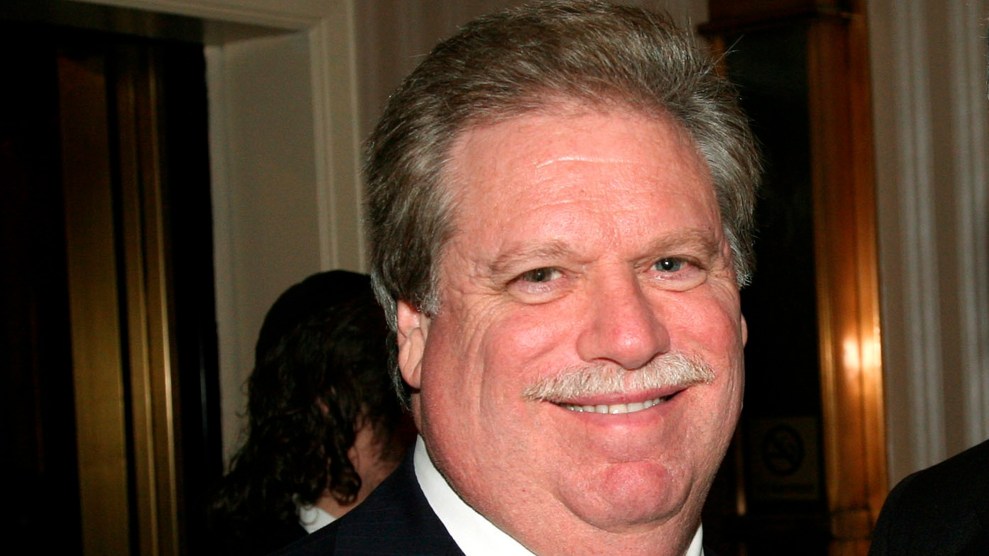

Elliott Broidy at an event in New York on Feb. 27, 2008.AP Photo/David Karp

In October, Elliott Broidy, once a top fundraiser for Donald Trump and the Republican Party, pleaded guilty to charges that he conspired to illegally lobby the Trump administration for a fugitive financier and the prime minister of Malaysia. The plea continued the descent of a controversial businessman and political operative who stepped down from a top Republican National Committee job in 2018 after the news broke that he had agreed to pay $1.6 million in hush money to a Playboy model whom he had impregnated during an extramarital affair.

Now there’s a new wrinkle to the Broidy case. He faces up to five years in prison in part because of what in retrospect seems to have been a dumb mistake. Broidy voluntarily gave the FBI emails from his and his wife’s accounts while seeking the bureau’s assistance in pursuing hackers who he claimed had stolen this material and leaked damaging details about his business dealings to the press. According to a just-unsealed ruling issued in June 2018 by Beryl Howell, the chief US District Judge in Washington, DC, nearly 1,400 pages of emails that Broidy provided to the FBI were subsequently used by the bureau in the investigation that led to Broidy’s guilty plea. Following a secretive legal process, Howell ruled that Broidy had surrendered the material to the FBI and after doing that—when the bureau wanted to exploit the documents for an investigation of Broidy himself—could no longer claim the information was covered by attorney-client privilege or spousal privilege.

A Broidy spokesman did not respond to a request for comment Wednesday.

Here’s what happened. Broidy owns a company, Circinus, that sells what it calls “open-source” intelligence services to foreign governments. In 2017, while the firm pursued a contract with the United Arab Emirates, which it later landed, Broidy emerged as an outspoken critic of Qatar, a regional rival of the UAE. Broidy helped to finance conferences and opinion pieces attacking Qatar as a sponsor of terrorism. That criticism dovetailed with attacks on Qatar by the UAE and its close ally, Saudi Arabia, which resulted in those and other Gulf nations imposing a blockade on Qatar in June 2017.

In late December 2017, Broidy’s wife, Robin Rosenzweig, who is an attorney, was targeted by a phishing attack. The hackers gained access to her emails and to Broidy’s. A few months later, media reports based on Broidy’s emails began to appear in major publications. The emails seemed to implicate Broidy in efforts to leverage his access to the Trump administration on behalf of various foreign interests, including officials in the UAE, Romania, Angola, Malaysia, and China. The leaked material raised the question of whether Broidy had broken the law by failing to register as a foreign agent.

Broidy responded in late March 2018 by suing Qatar, several lobbyists employed by the country, and others, alleging they had planned and executed the hack and the dissemination of his emails to discredit and silence him. “I knew that Qatar and its agents viewed me as an enemy,” he said in one court filing. (The lawsuits have since been thrown out due to Qatar’s diplomatic immunity, but Broidy has filed new cases against some of the defendants.)

At the same time, Broidy also asked the US Attorney’s office in Los Angeles, where he lives, and the FBI to investigate the hack. And he handed over samples of the hacked emails to the bureau.

That may not have been a smart move. Howell’s ruling reveals that the Justice Department had begun investigating Broidy for potentially illegal lobbying by the time he contacted the FBI about the hacking. Through a February 8, 2018 search warrant, the feds, according to the ruling, had obtained emails between Broidy, Rosenzweig, Malaysian businessman Jho Low, a GOP fundraiser named Nickie Lum Davis, and Pras Michel, the rapper and former member of the Fugees. Broidy was apparently unaware of the search warrant.

This year, prosecutors publicly revealed that the Justice Department’s Public Integrity Section had been investigating a scheme in which Low, the alleged architect of a massive embezzlement of funds from a Malaysian state investment fund known as 1MDB, hired Broidy to use his Trump administration connections to try to convince the Justice Department to drop an investigation of that matter. The 1MDB investigation threatened Malaysia’s then-Prime Minister Najib Razak, who has since been imprisoned there due to the scandal. Low also had a personal interest for which he needed Broidy’s help. US prosecutors had launched proceedings to seize hundreds of millions of dollars worth of assets that Low had allegedly obtained with stolen funds.

Michel and Davis had helped connect Low to Broidy, and Broidy, after insisting on a $1 million payment just to meet with Low, agreed to assist him for an $8 million retainer, with the chance to receive far more if the Justice Department dropped the case. Broidy’s ensuing work for Low included pushing for Trump to golf with Najib, who could use the time to request Trump’s help killing the 1MDB investigation, and an effort to convince the State Department that the 1MDB probe was harming US relations with Malaysia. Najib did not get a golf date, but he met with Trump in the White House in September 2017. To hide the payments from Low to Broidy, Low funneled money through a Hong Kong shell company, then sent the funds to accounts controlled by Michel, who moved the money to Rosenzweig’s law firm.

Broidy’s endeavors did not succeed. The US government did not drop the investigation and charged Low in 2018 with conspiring to launder money stolen from 1MDB. He remains a fugitive, but agreed last year to surrender $900 million in assets seized by the federal government as part of the probe. Davis pleaded guilty in August to aiding and abetting a violation of foreign lobbying laws. Michel, who faces charges in an unrelated campaign finance case, remains under investigation. Rosenzweig has not been accused of wrongdoing. After years of denying that he had illegally lobbied for overseas interests and disputing that he was under investigation, Broidy took that plea deal in October.

Back to the hacking case and Broidy’s emails: In April 2018—months after the FBI had launched its probe of Broidy—a lawyer representing Broidy and Rosenzweig gave the FBI 41 PDF files totaling 1,393 pages of the couples emails. These were files that Broidy and his lawyers had received from members of the media who had received them from anonymous sources. Broidy and his lawyers apparently hoped the FBI could use the files as evidence to track down whoever had hacked him. But Howell’s ruling states that the bureau asserted that its agents “made no representations or promises to [the attorney] or others, including Broidy, about how the emails would be used by the FBI.”

That ruling notes that FBI agents had already obtained some emails involving Broidy and Rosenszweig through the February 2018 search warrant and as a result, the FBI already had some unspecified portion of the material that Broidy’s legal team supplied. But the feds seemed to have viewed Broidy’s disclosure as an additional gift. The agents who received these PDFs turned them over to the team investigating Broidy.

In her June 26, 2018 ruling, Howell found that Broidy and Rosenszweig’s voluntary disclosure of those communications meant that “any claims of attorney-client privilege or marital communications privilege in those documents has been waived.” So the FBI could go ahead and use the emails to investigate Broidy.

But on April 18, 2019, Howell issued a new ruling, also unsealed this week, in which she partially reversed her earlier decision. In response to arguments from Broidy’s lawyers, the judge said that prosecutors had failed to sufficiently explain the year before that the emails Broidy had given to the FBI came from outside parties and that Broidy’s lawyer had removed material from this batch to avoid surrendering privilege. Howell vacated her decision that Broidy and Rosenszweig had waived their privileges. But she also said the crime-fraud exception—communication with a lawyer to advance a crime or fraud isn’t covered by the attorney-client privilege—gave the FBI a reason to use many of the emails.

And by then, the investigation into Broidy had advanced significantly. In July 2018, the FBI obtained two search warrants aimed at Broidy, according to Howell’s second ruling. Agents raided Broidy’s Beverly Hills office around that time, ProPublica reported last year.

In 2019, Broidy began negotiations that culminated with his recent plea deal, people familiar with the matter say. He is expected to be sentenced next year and can earn a reduced sentence, if prosecutors are satisfied with the cooperation he provides. Broidy has already agreed to forfeit to the government about $9 million he received from Low.

No one has ever been charged in connection with the hack of Broidy’s email.

Read Judge Howell’s rulings: