Voting in the Rockaway neighborhood of the borough of Queens, New York, after Superstorm Sandy in 2012. Craig Ruttle/AP

In May, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration predicted the approaching hurricane season, which runs from June through November, would be “above-normal.” By late September, the season had already seen twice the number of named storms of a comparable period. Hurricane Laura, the strongest hurricane to hit Louisiana since 1856, was responsible for about $10 billion in damage.

With less than a week before Election Day Hurricane Zeta, a category two storm, left over 2 million people without power in the South and at least six people dead after making landfall in Mississippi and eastern Louisiana. Meanwhile, residents in the West have fled wildfires that have engulfed millions of acres across Colorado, Utah, California, Washington, and Oregon, and states across the South are still picking up the pieces left by storms from earlier this year. By one estimate, more than a million Americans are displaced by natural disasters each year.

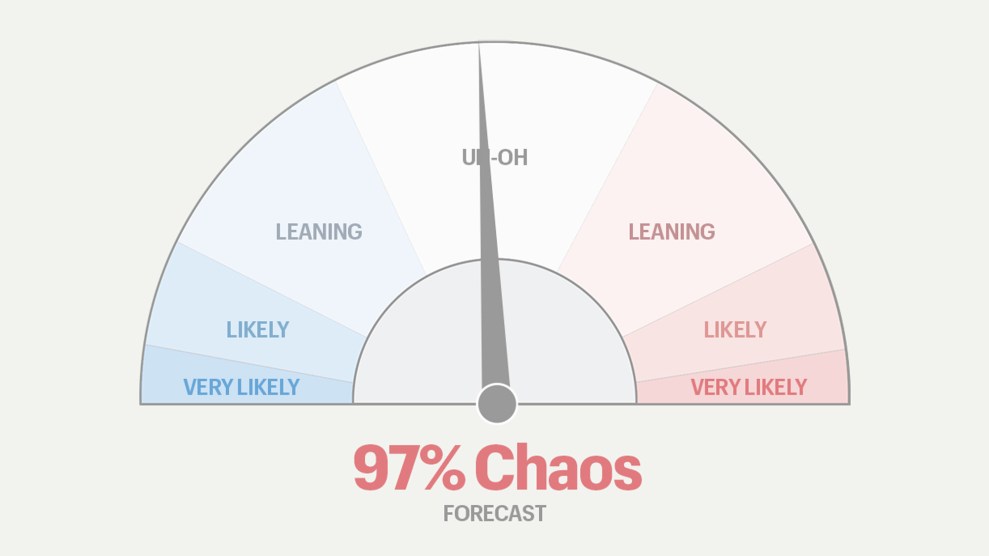

Against this backdrop, the most tumultuous presidential campaign season in modern history will culminate on November 3, a date that cannot be changed no matter how extreme the weather might be. As a result, states in potentially hard-hit areas have made extra efforts to insure votes can be submitted in a timely fashion. But what happens if portions of a state can’t participate in a national election due to an unforeseen natural disaster?

“You could have a redo, basically, on a subsequent day,” says Michael Morley, a law professor at Florida State University who has written extensively about Election Day emergencies. Federal law mandates that all presidential and congressional elections happen on the Tuesday after the first Monday in November, but allows states to postpone Election Day if necessary. “During the congressional debates that led up to the Presidential Election Day statute, one of the reasons for this provision was that somebody from Virginia said that they get a lot of flooding, and that people have trouble getting to the polls. Sometimes they’re not able to complete their elections. Natural disasters were one of the main things that the enacting Congress had in mind when they adopted this law.”

When Hurricane Sandy pummeled the East coast a week before the 2012 election, displaced New Jersey residents scrambled to vote by email and fax, overwhelming the county clerks charged with transmitting their votes. Meanwhile, in New York City, in-person voters faced long lines and ballot shortages. Four years later, Hurricane Matthew walloped North Carolina’s coast, and the state Democratic party successfully sued the state to extend the voter registration deadline for affected residents. Still, voter turnout dropped slightly in counties hardest hit by the storm.

One of the nation’s most devastating storms was Hurricane Katrina, which struck New Orleans in August 2005, killing nearly 2,000 people and causing $40 billion in damage. Municipal elections, including for mayor, scheduled five months after the storm had to be postponed an additional two months. “If Hurricane Katrina were to hit on Presidential Election Day, or the day before Presidential Election Day, it would be extraordinarily unlikely, I think, for the people in New Orleans, to be able to vote at a later point,” Morley says.

That’s a huge problem. Whether or not Louisiana would be counted in the electoral college without submitting its votes isn’t clear. “We don’t know what would happen if, for example, you had Mississippi, Alabama, Louisiana, and Florida unable to vote on Election Day,” says Norman Ornstein, a resident scholar at the American Enterprise Institute, a public policy think tank. “Do you postpone the whole election, which would require a change in the law? The idea that you’d have a do-over in a region of the country after knowing how everyone else had voted is fraught with peril.”

How prepared states are to handle an extreme event—whether a hurricane, earthquake, or a wildfire—on the eve of an election requires looking at what provisions are already in place, and how they’ve been used in the past. In the last two decades, multiple elections have been disrupted, but never thwarted. Still, even if a natural disaster doesn’t postpone the election, it could further complicate an already murky situation in states like Texas and Florida, where victory margins promise to be razor thin.

“Hurricanes, unlike efforts by some of our elected officials, are indiscriminate in whom they target,” says Daniel Smith, chair of the University of Florida’s department of political science. “The question is how well will local elections officials be able to respond—and to whom they will be responding—in those damaged communities.”

Most state governments have an array of tools to expand election access during a natural disaster. The governor, via the secretary of state, can extend deadlines for early voting and mail-in ballots, allow ballots to be forwarded to temporary addresses, permit local election officials to add new voting and polling places, or even postpone an election altogether.

In California, for instance, residents displaced by fires are not permitted to have their ballots forwarded to a new or temporary address, but they can re-register before or even on Election Day using a new address. In Santa Cruz, where the CZU Lightning Complex fire burned more than 86,000 acres in August and September, the county clerk’s office hosted biweekly Zoom meetings to keep displaced voters abreast of their voting options. They’ve also dispatched a “mobile voting unit” to shelters and other parts of the county to allow wildfire victims to register, vote, and request replacement ballots.

The Shasta County Registrar of Voters has said they plan to reach out to voters affected by the Zogg Fire—which destroyed more than 200 structures in late September and early October—who haven’t yet cast their ballots.

“Probably a week before the election, we are also going to go through our voter history file,” the registrar told the Sacramento NPR-affiliate CapRadio. “We probably will just do phone calls at that point to try and find folks and make sure they know what their options are.”

To the east, Colorado is in the midst of the largest wildfire season in its history, with firefighters battling East Troublesome, the second-largest blaze on record. After the fire incinerated an “unheard of” 100,000 acres in one day in October, a local sheriff called the spread, “the worst of the worst of the worst.” That could make voting difficult for the several thousand residents who quickly evacuated, especially if they’ve left ballots behind. Perhaps unsurprisingly, “[voting] may not be the highest on their priority list quite yet,” Angela Myers, county clerk in Larimer County where East Troublesome is burning, told the Colorado Sun earlier this week.

But in some ways, Colorado was already prepared. In 2013, the state overhauled its election system. As a result, voters automatically receive mail-in ballots, which they can submit at voter service and polling centers (VSPC) across the state—even outside the jurisdiction in which they’re registered. For registered votes who had to evacuate and left their ballots behind, VSPC also distributed replacement ballots. The Colorado Secretary of State’s Office also activated its electronic ballot delivery system for evacuees and firefighters, which allows them to print an emergency ballot and envelope.

Early voting has made a difference, in spite of still-burning wildfires. Colorado announced that it had already received two million ballots, nearly half of the number that were received by this time in the 2016 election. Almost 130,000 of those votes are from flame-ravaged Larimer County, only 50,000 short of the 2016 voting total. “All of those features were always good for voters,” said Amanda Gonzalez, the executive director of Colorado Common Cause, to the Colorado Sun, “[They] are particularly good for voters now.”

“Hurricane season is generally during voting season,” Hillsborough County, Florida, Supervisor of Elections Craig Latimer says. When Hurricane Andrew, a category five storm inundated the state in 1992, Latimer remembers contingency efforts used to bolster voting access. “I was with the Hillsborough County Sheriff’s Office, and I took folks down on a mutual aid response to Miami. We had this fabulous navy mess tent, and on the third day it was off limits—it became a voting site.” Asked if he was concerned about getting Florida’s electoral tallies in on time in the event of a hurricane, Latimer replies, “Hypothetically, no.”

In the run up to this year’s election, he says the Florida Supervisors of Elections have run “tabletop exercises.” But hurricane damage can be difficult to predict, and storms “are pretty specific in where they hit, they don’t hit the whole state.” Extra resources for voting in the aftermath of disaster are deployed at a local level, but, Latimer says, “It’s the state calling the shots.” Smith, from the University of Florida puts it this way: “I don’t really think it matters ultimately what’s in that tool box, because it’s the governor who’s going to determine whether to open it or not.”

The state’s current governor, Republican Ron DeSantis, hasn’t been keen to expand voting access, one need only look at his efforts to prohibit convicted felons from voting, despite a 2018 statewide ballot where Floridians voted to end the state’s longstanding ban. “My fear is that political calculations might rule the day, rather than making sure that all voters have an opportunity to exercise their vote in the eyes of a storm,” Smith says.

In October, 2018, Hurricane Michael slammed into Florida, causing $25 billion in damage and throwing state elections into disarray. Within days, secretary of state Ken Detzner announced orders to expand early voting and gave local election officials permission to add voting sites. Notably, Detzner only extended voter registration by a single day in counties where election offices were closed by the storm. In Bay County, the local supervisor of elections opened controversial “mega-voting sites” that the local NAACP chapter said were geographically inaccessible to the Black community.

Even small disruptions, or ones that are limited to a specific location, could have huge implications if they happened during a national election. The 2000, the presidential contest between George W. Bush and Al Gore was decided by a margin of fewer than 600 votes.

In 2020, things are even more complicated. With the pandemic, Smith estimates that half of the state’s10 million votes this year are being cast early or by mail. By Election Day, many more voters will have cast their ballot than usual. A hurricane might disrupt more mail-in votes if it strikes before November 3, but a voting day storm would be less of a threat. “The more people take advantage of things like early voting, in-person absentee voting, absentee voting, the more opportunity there is to mitigate, or at least lessen the impact of a cataclysmic event like Katrina on Election Day, or, the day or two before Election Day,” Morley explains.

Florida may have an array of election disaster tools, but Texas has an actual manual. The state’s plan for election-day natural disasters is summed up in three words that appear four times in their manual: “Voting Must Continue!” The Texas Secretary of State’s election disaster planning guidance, says that in cases where elections offices or polling stations lose power, or are inaccessible due to floods or structural damage, the state recommends election officials have back-up generators or batteries on hand. If all else fails, they tell officials to relocate affected polling locations.

There’s no official procedure for relocating polling stations laid out in Texas’ election code, so the logistics are left to local officials. (A spokesperson for the Secretary of State’s office told Mother Jones they do provide county election offices “with templates regarding continuity of operations, incident response, etc.”) Local officials are also permitted to close polling locations at their discretion, but need a court order in order to extend voting hours at any given location. If disaster strikes before Election Day, the Secretary of State’s guidance explains that “[a]dding additional hours is usually not necessary since the early voting period allows a large window for voting.”

The Texas Secretary of State also has a FAQs page specifically for evacuees who want to vote, but most of the guidance is to assist voters with registering in new home counties or applying for absentee ballots. Texas voters who lose important documents in disasters are allowed to waive voter ID requirements, but they have to cast a provisional ballot that only counts if a natural disaster affidavit is submitted shortly after the election. The website reassures voters, “Even during this difficult time, it is still the voter’s responsibility to make certain decisions as to what he or she considers home in time to vote, and to file the necessary paperwork. As to your ballot being counted, Texas counties count ballots mailed to them from applicants from all over the world.”

In the aftermath of Hurricane Harvey, the deadliest storm to hit Texas in nearly a hundred years, the NAACP’s Legal Defense Fund sent multiple letters to the Secretary of State, warning that strict voter ID requirements combined with the disproportionate impact of the disaster on low-income communities of color would further disenfranchise an already vulnerable group of people ahead of the November 2017 statewide elections. Even the natural disaster affidavit process, which was meant to address that problem, was insufficient, they said.

“It is unrealistic to expect a vulnerable population of displaced victims of the hurricane to travel to vote on or before Election Day, and then later return to the Registrar’s office to execute an affidavit,” the NAACP wrote. “This two-step process will effectively deny victims of natural disaster their right to vote.

But despite provisions that allow for postponing Election Day, the Constitution is far less lenient with Inauguration Day and a handful of other election deadlines between early November and January 20. On December 14, each state’s electors get together to officially cast their votes for President, and it could be considered unconstitutional if all votes aren’t submitted on the same day.

“One of the giant black holes of the Constitution is what happens if a state doesn’t wind up finishing their vote count for a month and a half?” Morley says.

Disaster recovery is a long, drawn out process, but elections aren’t supposed to be. Although the Constitution allows for the popular vote to be postponed if necessary, it doesn’t say anything about the Electoral College’s contingency plans. There’s no clear solution to the worst case scenario: A state so damaged that it’s incapable of conducting a legitimate election on the timeline set by a national election. Whether the electoral college would wait for a state with an interrupted election to submit its delegates, or even count them at all, isn’t clear. “There’s no plan for a postponement,” Ornstein, AEI’s resident scholar, said. “None of these are easy issues to answer.”

According to Ornstein, the problem with past election disruptions is they’ve never been destructive enough to force change. “We don’t tend to do things in a government that doesn’t act easily to begin with, unless and until there’s a crisis,” Ornstein, who’s been raising the alarm on constitutional crises that could come out of this election, said. “If it passes and there aren’t consequences, it’s easy to let it go.”

Sometimes, lightening needs to strike twice. “We’ve had instances in which presidents were assassinated without an adequate plan in place for succession,” Ornstein said. Even then, “It took two presidential assassinations to get a change in the Presidential Succession Act.”