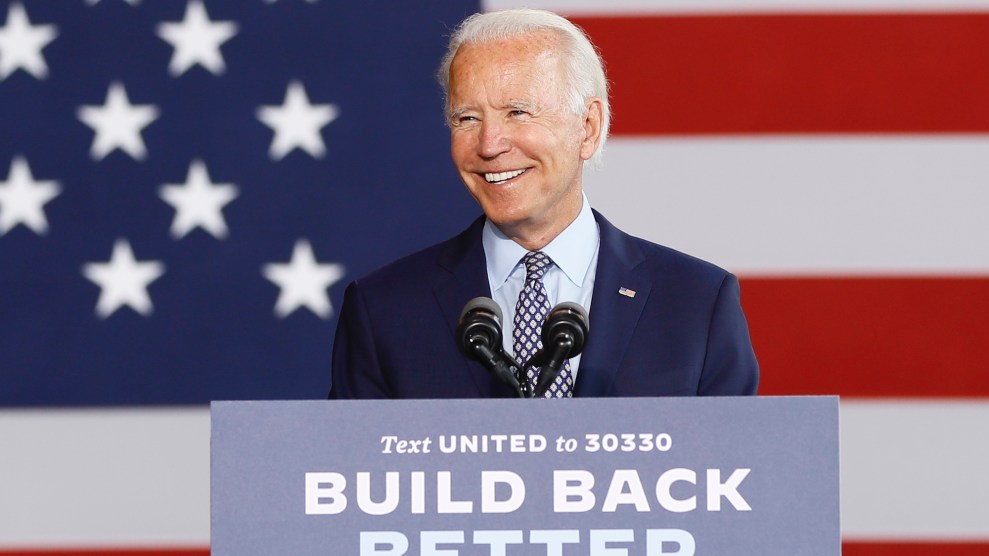

Joe Biden’s euphoric campaign staff had overtaken Philadelphia’s National Constitution Center. It was March 10, and Biden’s three primary victories that night, with two more on the way, all but confirmed he would be the Democratic nominee. The celebration for the momentous feat was supposed to be at a large rally in Ohio, not in a foyer in a museum down the street from his campaign headquarters, but as the coronavirus gained a toehold in a few US cities, a large gathering was deemed too dangerous. The shift in venue, for the moment, did nothing to dampen staffers’ spirits as they rushed to embrace one another and danced awkwardly to a Whitney Houston remix that blared through the speakers after their boss finished his victory speech.

Back at Biden HQ, the quartet of television screens hung along an office wall began to broadcast grim news about the staggering rate of infections and possible death toll. The next day, the World Health Organization would declare COVID-19 a pandemic, and smaller gatherings, too, would soon be scrapped. The outbreak would not only curtail future campaign events, but also plunge the nation into a public health crisis, the likes of which the country hadn’t experienced in a century.

Until that point, Biden had threaded the primary gauntlet with a message based on big-picture themes—electability, experience, and his frequent campaign pledge to restore America’s “soul.” For much of the campaign, his policy shop consisted of just three to four generalists huddled at a few desks near the communications team in Biden HQ; they produced a platform that largely hewed to Democrats’ consensus agenda. But as the coronavirus spread misery and death through March, it became clear that the nation’s soul might not be the first thing that needed saving in a Biden presidency.

By April, the Biden team had begun fleshing out its policy ranks with dozens of outside advisers. Jake Sullivan, who became Biden’s senior policy adviser this summer, organized two daily Zoom briefings for the presumptive Democratic nominee: One with public health experts and another with economists. But just as Biden assumed the mantle of the Democratic Party, Bloomberg reported that one of those advisers was Larry Summers, the Harvard economist who served as Treasury secretary during the Clinton administration and as chair of the National Economic Council—which drives the White House’s economic strategy—under Obama. A reviled figure on the left, he epitomized a coziness with Wall Street that they had hoped to purge from the party. Among progressives who favored Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren, Summers’ apparent role confirmed that Biden was the status quo candidate they’d believed him to be. In May, more than two dozen left-leaning groups—from MoveOn to Greenpeace to the Justice Democrats—signed a letter demanding Summers’ removal from the campaign.

The Summers contretemps quickly died down (and Summers later announced, to the relief of the left, that he was leaving politics altogether). But to the Biden camp, the episode was exactly the type of intraparty skirmish they had hoped to avoid. Since the Obama years, economic policy had become the bloodiest theater of Dem-on-Dem clashes, and Biden still hadn’t fully won over the supporters of his former primary opponents. In its aftermath, the campaign became increasingly reticent to discuss who Biden was turning to for economic advice. Stories written on the subject skated over the specifics and produced headlines such as this one from the New York Times: “Biden’s Brain Trust on the Economy: Liberal and Sworn to Silence.” Aides downplayed the influence of individuals while taking pains to stress that they’ve cast a wide net to include the whole spectrum of Democratic thought, ranging from Obama-era bureaucrats to the sorts of lefty thinkers embraced by Bernie Sanders.

Still, I wanted to understand who was shaping the Democratic candidate’s economic vision, since the economy would be an immediate and critical battlefield for a Biden administration. I spoke with nearly 40 campaign aides, outside experts, Democratic operatives, and Obama administration alumni who pointed me in the direction of the three PhD economists who have regularly briefed Biden since the beginning of the pandemic: Jared Bernstein, Ben Harris, and Heather Boushey. Each hail from distinct wings and eras of Democratic economic thought. Bernstein, who served as Biden’s chief economist in the White House, is a lefty labor-aligned thinker who has been waiting for the political moment to meet his ideas. Harris, who succeeded Bernstein, came up through a neoliberal branch viewed with suspicion by progressives but has emerged as a key translator for Biden’s populist and pragmatic tendencies. Boushey is a liberal economist whose ideas about inequality—particularly, how it affects families—have made her a wonk for this time of pandemic and peril. While each of them are informal advisers with no official campaign role, they have been key influences on Biden’s economic thinking and plans, and will likely continue to be if Biden wins the White House.

If elected, Biden will inherit an unprecedented economic crisis. Unlike the 2008 meltdown, this mess is complicated by a virus that does not respond to Keynesian remedies. But one lesson does carry over: The wonks in the room matter. Biden is likely to face a familiar political dynamic: a progressive movement wary of his centrism and a Republican Party horrified anew by government spending with Biden in the White House instead of Trump. What will Biden consider as he navigates treacherous economic conditions and political dangers? The cadre of economists who regularly have his ear provide some hints.

Jeff Connaughton, a longtime Biden aide, offered a scathing view of his former boss’s economic acumen in a 2012 tell-all memoir: Biden and Obama were “financially illiterate” when they entered office and took charge of (what was then) the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression. During his 36-year Senate career, Biden was best known for chairing the Foreign Affairs and Judiciary committees, neither of which directly dealt with economic matters. Hailing from Delaware, a state where corporations outnumber citizens, he became known as the “Senator from MBNA,” and he famously championed a 2005 bankruptcy bill backed by big banks and credit card companies that made it harder for debt-ridden Americans to relieve their obligations to creditors.

“I think Biden in 2005 was pretty different in this space than he was in 2009—he’s really different,” Jared Bernstein told my colleague Tim Murphy last year. Indeed, bearing witness to the economic carnage of the last recession reshaped much of Biden’s thinking. But so, too, did Bernstein, the man chosen in December 2008 to fill the newly created role of chief economist to the vice president.

Bernstein was a bit of an oddity among the team of Harvard, MIT, and University of Chicago-trained economists in the Obama White House. For one thing, his first passion was music: He’d spent his undergraduate years studying jazz double bass at the Manhattan School of Music. A stint as a New York City social worker inspired Bernstein to pursue a PhD in social welfare at Columbia University, where Bernstein learned traditional economics, but as a means to examine how markets had failed vulnerable populations. He became enchanted with the work of John Maynard Keynes, the British economist best known for prescribing government intervention during economic downturns, an idea that challenged the notion—especially ascendant during Bernstein’s grad school days in the 1980s—that free markets fixed themselves. Bernstein is still quick to rhapsodize on the long-dead scholar who nudged FDR to spend expansively on the New Deal. “If you read Keynes,” he told me, “you’ll see something else that I try to live by: an unending optimism that we can do better—that good, inclusive, empirically driven ideas can beat out bad ones.”

Bernstein arrived in Washington in 1992 to work under labor economist Lawrence Mishel at the Economic Policy Institute, a left-leaning, labor-aligned think tank founded six years earlier at a time when pro-free trade, anti-union philosophy dominated economic thought. The duo—”the Lennon and McCartney of economics,” Mishel recalls Bernstein calling them—uncovered what was then a new and concerning development: The economy was more productive than ever, but workers’ wages remained flat. They placed the blame for that on the policy choices that had decimated worker power. “[Bernstein and Mishel] were pushing that at a time when that was seen as a very, very strange view,” says Dean Baker, a labor economist who worked with Mishel and Bernstein at EPI and co-authored books with Bernstein on full employment.

Jared Bernstein at a town hall meeting on the economy at the White House in March 2009.

Mandel Ngan/AFP/Getty

Not surprisingly, they found themselves at odds with top economists in the Clinton White House, populated by disciples of deregulation, such as Larry Summers and Robert Rubin, who had blamed the plight of American workers on automation. Bernstein spent a year working as a junior economist in Robert Reich’s Labor Department, though he largely focused on pushing the Clinton administration to the left from outside the government. Occasionally, he penned essays for the American Prospect, the magazine co-founded by Reich, where he made clear that he saw neither political party as friendly to his beliefs. In a 2002 piece, Bernstein bemoaned “the ceaseless and sole emphasis on supply-side economics” in which Democrats prescribed job training and Republicans prescribed tax cuts. “You’ve got to be willing to mess with markets,” he wrote. “You need to embrace the conviction that there are times when the invisible hand needs a nudge in the right direction.”

During the 2008 Democratic presidential primaries, Bernstein lent his expertise to all of the candidates running—though he favored John Edwards’ populist economic agenda. Once the field narrowed and the economy jumped the tracks, he became a more regular adviser to Obama. “I think he reached out to progressive economists, among others, who had a narrative similar to his own,” Bernstein recalls of Obama. “Among others” turned out to be the same Rubinites Bernstein had clashed with more than a decade earlier.

After Obama’s victory, Summers took the helm of Obama’s National Economics Council, while Timothy Geithner was installed as Treasury Secretary. Bernstein was hired as Biden’s adviser, a match in keeping with Biden’s touted ties to labor and the vice president-elect’s interest in ensuring ways the economic recovery could, in particular, boost the middle class. Among his new White House colleagues, Bernstein almost always represented the most liberal perspective in the room, though he tried to downplay any tensions at the time; he and Rubin even wrote a New York Times op-ed together to prove it.* But his view was not always welcome. Baker remembers Bernstein recounting an uncomfortable episode with Summers after Obama invited Bernstein to join a meeting of his top advisers. “Obama sees Jared and goes, ‘Oh, why don’t you come to this?’” Baker recalls. “And apparently Summers is glaring at him the whole time, like ‘What are you doing here?'”

Bernstein advocated for an “all gas, no brake” approach to the stimulus that the Obama White House was crafting to revive the economy, wanting more than what some of his White House colleagues and the politics would allow. He liked the idea of singling out US manufacturing for government support to resuscitate failing industries, even when Obama’s other wonks were much more skeptical. As journalist Michael Grunwald explained in his book, The New New Deal, Bernstein heeded Obama’s call for transformational New Deal-style programs, pitching programs akin to a Works Progress Administration, such as grants to help cities hire the unemployed for a range of jobs, such as cleaning up blighted neighborhoods and digitizing public records. Biden had been a champion of the administration’s job creation efforts, but Bernstein’s specific ideas ultimately went nowhere. “There wasn’t a lot of appetite for a new WPA,” Bernstein told Grunwald.

Democrats and economists of nearly all walks now agree that the stimulus was too small, but Republicans couldn’t be persuaded to pass another package, and in the 2010 election the Obama administration paid the price. Democrats lost control of the House of Representatives, and the White House signaled a return to balanced budgets and austerity. Bernstein left his job with Biden a few months later. In May 2011, he reemerged with a new blog, explaining that his departure had not been, “as some accounts suggested, because ideas that I was associated with, like more stimulus, are off the table”—though he added he was “not happy about that.” Instead, he said he had been frustrated with the political economic discourse. “When you’re on the inside at a time like this, you’re constantly balancing the risk of losing the support of people you need to lead,” he wrote. “I’m going to try to do my part to improve the debate from the outside.”

The vice president’s chief economist post sat vacant for three years after Bernstein’s departure. A GOP-controlled House held the hopes of further recovery funding hostage, and when Republicans seized control of the Senate during the 2014 midterms, the rest of the Obama administration agenda was about to be railroaded, too. After those midterms, Steve Ricchetti, then Biden’s chief of staff, reached out to an economist from a different school of thought than Bernstein’s to fill the role: Ben Harris, policy director of the Hamilton Project, a neoliberal think tank within the centrist Brookings Institution that had been founded by Robert Rubin.

Politics had been Ben Harris’ first love; economics, by his own admission, was an accident. As a high schooler on Bainbridge Island in Washington state, he was a sports busybody, student body treasurer, and attended Boys Nation, the highly selective weeklong government crash course for high school juniors in DC, where he met then-President Clinton. At Tufts University, he majored in economics because it offered an easier pathway into the school’s competitive semester in Washington program. “It was a good early lesson in game theory—a branch of economics that accounts for the actions of others when deciding what’s best for you,” Harris told his hometown newspaper in 2015.

Save for completing his undergraduate work in 1999 and a pair of masters’ degrees from Columbia and Cornell, Harris never really left DC after that Washington semester. He took a job at Brookings working under William Gale, a Brookings fixture who had briefly served as an economist in George H. W. Bush’s administration. Their research focused primarily on taxes and budgets; their conclusions often warned of the nation’s unsustainable fiscal deficit while calling for tax increases, often on high earners. Their proposal for a value-added tax—essentially, a sales tax on every stage of the production process—gained traction among lawmakers in the wake of the Great Recession to fill the gaping fiscal hole the downturn and stimulus spending caused. As he churned out white papers by day, Harris attended classes for his PhD at George Washington University at night.

Gale recommended Harris to Austan Goolsbee, chair of Obama’s Council of Economic Advisors—the White House’s in-house economic think tank—who was looking for someone with a public finance background to round out his team of staff economists. Harris had plenty of experience in that and, unlike the typical CEA egghead, he’d actually done policy work in Washington, not academia. Among his projects, he provided the research underpinning Obama’s proposed 2012 corporate tax overhaul that would have lowered the corporate tax rate to 28 percent. His unrealized recommendations have resurfaced in Biden’s campaign platform (though Biden now wants to raise the tax to that rate after Trump slashed it to 21 percent). In 2013 he went back to Brookings, but was back at the White House nearly two years later.

The role of chief economist had been resurrected because Biden, in the twilight of his vice presidency, wanted to dive back into economic policy. By the end of 2014, unemployment had retreated from its Great Recession peak, but as the recovery unfolded, Biden had two chief concerns. One was stagnant wages—a side effect, Biden believed, of weakened worker power. Another had to do with a troubling corporate trend: Public companies that had received massive infusions of taxpayer funds at the dawn of the financial crisis were now using their earnings to buy back their stock, a strategy that improved share prices and passed that value onto investors, not workers. Before taking the job as Biden’s economic adviser, Harris met with the VP’s policy director, who plopped a tall stack of literature on stock buybacks down in front of him. “From a macro perspective, things were looking pretty good,” Harris told me this spring, “but when you looked under the hood, things weren’t so good.” (Harris declined to comment for this story.)

Ben Harris hosts a panel at a Brookings Institution-Biden Foundation event in 2018.

C-SPAN

With the House and Senate firmly under GOP control, the only available pathway to achieving any of Biden’s ambitions would be through executive orders, which offered some success: In May 2016, Biden announced new rules that extended overtime benefits to more than 4 million workers. (The Trump administration has since rolled it back). During his second stint in the Obama administration, Harris encountered a vice president whose ideas about labor in the post-Great Recession economy had been pretty firmly set, thanks in no small part to the work he’d done with Bernstein. Harris brought his own set of pet issues: taxes, budgets, corporate governance, and public investment. Biden showed an openness to new ideas Harris brought him; unlike Obama, who often leaned on his economic advisers for a final-sign off, the vice president and his chief economist would have hours-long discussions about economic philosophy. Over the next two years, an economic vision emerged that bore the influence of both Harris and his predecessor—and previewed economic themes like worker protections, a modern tax code, and improved infrastructure that would define Biden’s 2020 run.

Harris kept a lower profile than his predecessor, but Harris’ former White House colleagues have described him as a Biden whisperer, someone who demonstrated an encyclopedic knowledge of the vice president’s positions and a loyalty to put them above any of his own. “I think that he feels unusually comfortable with the vice president, and I think they communicate a lot, they see eye to eye,” says Adam Looney, an economist who preceded Harris as the Hamilton Project’s policy director. “And I think he’s good at identifying what the vice president wants to achieve and channeling them.”

When the Obama administration ended, Harris advised an asset management company and opened his own consulting firm, but he never really left Biden’s orbit. He worked with the former vice president on his speeches, wrote occasional policy memos for Biden, and edited the Biden Forum, a blog that elevated ideas from a cross-section of Democratic wonks on the future of the middle class. Harris’ recent research on competitive labor markets showed up in a 2018 speech Biden gave on conditions to support higher wages. When Biden weighed whether to enter the 2020 race, Harris was among a small group of former aides he consulted, and Biden brought Harris on as an informal economic adviser as soon as the campaign kicked off.

Harris and Bernstein were old Biden hands, but in March the campaign recruited another economist: Heather Boushey, the president and CEO of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, a left-leaning economic think tank spun off from the Center for American Progress.

Boushey’s upbringing in the 1970s Seattle suburbs was an object lesson in the middle-class squeeze. Her father was a union machinist who built for Boeing; her mother worked as a bookkeeper to make ends’ meet. When Boeing laid off Boushey’s father in the early 1980s, her mother told her middle school-aged daughter that her swim team membership, $100 a month, might be on hold until her father resumed work. “That was the moment that I realized that actually economics—whether or not my parents have a job—affects whether or not I get to do the things that matter to me in my life,” she told the New York Times earlier this year. (Boushey, who has a strict policy of not discussing her work with the Biden campaign, declined to comment for this story).

Boushey resolved to become an economist in high school; an AP US History teacher suggested it might be the best application for her exceptional math skills and nascent fascination with political philosophy. But she got there via an iconoclastic route. She attended Hampshire College, the avant-garde liberal arts school where students design their own curriculums and receive written evaluations in lieu of grades, and then an economics PhD at the New School, a program at the New York City institution known for producing scholars who challenge neoclassical economic thought. (In the staid world of DC professional fashion, Boushey is the sort who showed up for that recent New York Times interview wearing a Stephen Malkmus and the Jicks t-shirt.)

Heather Boushey, testifies on Capitol Hill in 2011.

Manuel Balce Ceneta/AP

Her unconventional training prepared her for a career in DC’s left-leaning think tanks: Boushey cycled through EPI and the even-leftier Center for Economic Policy and Research before she landed at the Center for American Progress in December 2008. Her early research, like Bernstein’s the previous decade, argued that boons of a productive economy were barely realized by its workers, but she zeroed in on a particular symptom of wage stagnation she’d seen in her childhood: How women moving out of the home and into the labor market created its own set of expensive disruptions. Boushey frequently appeared on Capitol Hill to testify that raising the minimum wage, paid sick leave, and affordable childcare weren’t the job killers they’d long been touted as, but crucial to a productive economy because they reduced absenteeism and workforce turnover. The Great Recession’s path of destruction only served to crystalize what Boushey had observed about the structural weaknesses that left families vulnerable.

Boushey first met Biden in 2009 when she participated in a roundtable for the vice president’s Task Force on the Middle Class, but she would end up being another Democratic politician’s star wonk. She joined Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign as one of its first informal policy advisers. Clinton’s first major economic address of the campaign—delivered at the New School, Boushey’s alma mater—touched on Boushey’s greatest hits: A decline in workforce participation among women, childcare, and paid family leave. Throughout the campaign, Boushey would raise her argument that equality and economic growth go hand in hand to defend Clinton against attacks from her opponent, Bernie Sanders, whose own run prized redistribution above all else.

“Heather [looks] at how a society treats its workers—in the beginning of her career, women workers, but now all workers—as a way to judge a society,” says Teresa Ghilarducci, a economist at the New School who, like Boushey, informally advised Clinton’s campaign.

As the campaign neared the general election—and Clinton’s victory looked all but guaranteed—Boushey was named chief economist of Clinton’s transition team and she was rumored to be in the running for a top economic post in the new administration. But, of course, Clinton didn’t win. Boushey returned to the think tank she founded and wrote a new book on inequality and its drag on individual and aggregate growth. As the 2020 race heated up, Boushey’s advice was consulted by nearly all of the candidates, but once the pandemic hit, her ideas became urgent. “There’s kind of two core ideas that have animated a lot of Heather’s work: One is about gender and the economy, and one is about inequality in the economy more broadly,” says Michael Linden, a founder of the Groundwork Collaborative, a left-leaning economic think tank. “Both of those are ridiculously relevant right now.”

The Build Back Better plan, Biden’s four-pillar federal stimulus proposal developed in the wake of the coronavirus crisis and introduced in July, is in many ways a redo of the 2009 stimulus law—a combination of public spending and tax credits—except with far more ambitious goals: $2 trillion to boost clean energy and infrastructure, $300 billion to spur US-based research and development, $400 billion aimed at American manufacturing, a $775 billion caregiving proposal, and billions more to fund clean energy and address stark racial inequities that the coronavirus crisis laid bare. And every Biden aide goes out of their way to stress that the ideas are all Joe Biden’s. After nearly a half-century in federal office, they argue, the former vice president knows who he is and what he wants.

“I understand why some people are trying to pinpoint where the vice president is headed based on who is advising him, but I think, respectfully, that is the wrong way to do it,” Stef Feldman, the Biden campaign’s policy director, tells me. “It almost also doesn’t matter who is advising him because they are not shaping his values and principles. They are shaping the data that gets input so he can shape policies that align with those principles.”

The data, of course, matters—it’s the grounding Biden leans on to move comfortably on any policy decision. Sources close to the campaign say Harris hews a little closer to Biden’s own political instincts: While quite liberal on matters of labor, he’s been described as a more moderate influence, primarily in the way he raises concern about what the long tail of Biden’s proposed several trillions in stimulus spending might do the country’s fiscal stability. “I worry really deeply about the deficit—I have for my entire career and that hasn’t changed,” Harris told me in July, but added that he supports swift and intense government intervention in emergencies like the one currently facing the country. “If moderate means that he thinks about the costs as well as the benefits, then yes, he’s a moderate,” William Gale, Harris’ old Brookings boss, tells me. “If moderate means pessimistic about what government can do, then no, I don’t think he’s a moderate.”

Bernstein and Boushey, meanwhile, are among those urging Biden to the left and to embrace more ambitious proposals. “I’m really delighted that both of them are there,” Dean Baker says. “They bring somewhat different perspectives, but they’re both very important. And, you know, to my view, it’s a world of difference from 2009 when Jared was there but very much on the outside, and Heather wasn’t there at all.”

If you look closely at Build Back Better, you see the trademarks of Bernstein, Boushey, and Harris. The various fiscal and monetary recommendations for getting to full employment show Bernstein’s touch. Aspects of Biden’s proposal to expand affordable child care—and to pay those who provide that care well—appears lifted from the pages of Boushey’s book on the subject, Finding Time. The $4 trillion tax proposals to pay for the permanent pieces of the plan are, as Gale put it to me, Harris’ “bread and butter.” (Bernstein also reunited with a conservatory classmate to write a theme song for the proposal.) Where Biden may have entered the White House last time with economic views shaped more by his home state’s pro-corporate ethos, it’s clear Bernstein and Harris’ stints working with him at the White House led to different, more sophisticated views on the economy, and since Boushey joined the squad, Biden’s plans have reflected more expansive thinking than they did during the primary.

In the campaign’s final stretch, Harris has continued to work closely with Jake Sullivan on the development of economic-related policy. Boushey led an outside advisory group of hundreds of economists shaping how Biden might turn his campaign platform into executable policy. Bernstein has joined the transition’s advisory board. The economic briefings have continued, but on an ad-hoc, not daily, basis. On a campaign that’s been conducted largely over Zoom and email, it’s impossible to gauge what influence any one person is having, and that influence can vary from day-to-day. A broader group of regulars—including Austan Goolsbee, former Clinton and Obama NEC chair Gene Sperling, and AFL-CIO economist Bill Spriggs—also weigh in on policy details. Jeff Zients, another Obama NEC chair and a wealthy investor with deep business ties who now co-chair’s Biden’s transition team, also has the candidate’s ear on economic matters. And, of course, there’s a tight-knit team of longtime political advisers who touch every decision Biden makes.

In the words of one Obama administration alum who knows all three well, they feel confident in Bernstein, Boushey, and Harris’ influences because “you can see the imprint of their work in what’s happening” and “they fit very clearly into the vice president’s mindset” about the current crisis. “It’s a team that helps you manage, if you’re a president, your human capital in your society,” the New School’s Ghilarducci said, citing Bernstein’s focus on the poor, Boushey’s emphasis on workers, and Harris’ technical expertise.

The tea leaf reading is about to be rendered moot, anyways. If Biden wins, he’ll set in motion a massive transition operation that will bestow official government titles, and Bernstein, Boushey, and Harris are all expected to have some kind of role. Some progressives are pushing to see Boushey chair the CEA and for Bernstein to get a promotion to NEC chair (though folks in the Warren and Sanders wings of the party will tell you that Bernstein and Boushey are not as progressive as the people their candidates would have hired.) The opinions speak to the fact that the relationship between the moderate and progressive wings remain uneasy.

Democrats have uniformly gotten over whatever sticker shock plagued the 2009 recovery—especially since Congress already passed $2.2 trillion in stimulus earlier this year. The deficit hawks have been relatively assuaged by the fact that interest rates—the key ingredient to making a bad debt worse—have remained low, and they accept the ongoing recession will only be remedied by a massive cash infusion. What a President Biden would hope to pass in January probably looks a lot like the $3 trillion program the House Democrats passed in June.

It’s what comes after this stimulus that might trigger a fight within the party, with friction between those in Biden’s ranks pushing for bolder policies and those more cautious about the political impacts. Boushey, at least, has hinted that she (and likely Bernstein) is already thinking about more ambitious structural change. Speaking to the New York Times last week, Boushey noted that a “timely, targeted, and temporary” stimulus made sense for the 2009, but not now. “This problem feels different,” she said, “because it’s unearthed these really important structural challenges that need to be solved.”

A lot could stand in the way of even the most modest planks of Biden’s platform. Without an end to the Senate filibuster—something Biden has yet to support—there’s a good chance Senate Republicans can block his promised policies, even if they are bounced to the minority. But how the White House approaches those battles will begin with which wonks control the flow of information that reach a would-be President Biden and shape whether he ends up championing a massive social works program that restructures the economy or a band-aid that patches up the problems of pandemic-era America.