An armed man in Kenosha, Wisconsin on August 25, the night two people were killed by a vigilante.Chris Juhn/Zuma

Three months after the 2016 election, in which Facebook facilitated the spread of fake news stories and disinformation from Russia, the company announced a pivot. Under pressure, Facebook laid out plans to “build a safe community that prevents harm” and “helps during crises,” with “common understanding” and increased civic engagement. The company said the path to this better world would go through the platform’s groups function, which Zuckerberg touted as a way to “support our personal, emotional and spiritual needs” and build “social fabric.”

But instead of ushering in a new era of community and safety, the social media giant’s decision to prioritize the discussion spaces bred disinformation and vigilantism. Facebook groups have been used to organize armed responses to this summer’s protests that have turned deadly, a track record that suggests they could fuel chaos during or after this November’s election, catalyzing violent reactions and disseminating destabilizing false information.

Groups “are the biggest vulnerability the platform has,” says Nina Jankowicz, a fellow at the Wilson Center who has studied them as part of her research into disinformation and democracy. When using private groups, Facebook users are primed to think they are in safe, trusted spaces, which she says heightens their vulnerability to radicalization and disinformation. Even inside the groups, Facebook’s algorithms prioritize sensational content.

Facebook made another fateful decision last year that made groups even more dangerous. In April 2019, the company announced a “pivot to privacy,” a response to both the increasing popularity of rival private chat forums like Discord, and a reaction to the Cambridge Analytica scandal in which Facebook failed to protect user data. As part of this reorientation, Facebook made groups even more prominent, redesigning its platform to push more of them to users. “Groups are now at the heart of the experience just as much as your friends and family are,” CEO Mark Zuckerberg explained. According to internal memo written this August and leaked to the Verge, posts to groups grew 31.9 percent over the previous year.

Taken together, the steps have created a radicalizing platform with the potential to unleash damage far worse than in 2016. Closed groups now exist as a largely unpoliced, private ecosystem, where users can quickly spread content that will largely remain off-the-radar—including from journalists and Facebook’s own moderators—who are not inside the spaces. Both private and public groups can become spaces for planning and coordinating violence, which Facebook’s moderators and artificial intelligence tools have proven unable—and perhaps unwilling—to stop.

In July, Jankowicz co-authored an op-ed in Wired warning about the danger of Facebook groups and the role they can play in radicalization:

If you were to join the Alternative Health Science News group, for example, Facebook would then recommend, based on your interests, that you join a group called Sheep No More, which uses Pepe the Frog, a white supremacist symbol, in its header, as well as Q-Anon Patriots, a forum for believers in the crackpot QAnon conspiracy theory. As protests in response to the death of George Floyd spread across the country, members of these groups claimed that Floyd and the police involved were “crisis actors” following a script.

Jankowicz’s example maps closely to trends that arose after the first waves of stay at home orders in response to the coronavirus, which pushed American lives to migrate even further online. Membership in Facebook groups about health began to circulate content about the coronavirus, including some skeptical of its existence or severity. New groups arose to push to immediate re-opening after lockdowns, which included crossover to militia groups and white nationalists. Some of these groups have also featured users pushing the QAnon conspiracy, whose adherents believe President Donald Trump is rescuing children from a deep state sex-trafficking cabal, among other insane ideas.

Facebook’s recommendation algorithm plays a big role in this pipeline by recommending similar groups. “That’s where the bubble generation begins,” a Facebook engineer who works on groups told the Verge, explaining how the company’s programming profiles and then isolates people. “A user enters one group, and Facebook essentially pigeonholes them into a lifestyle that they can never really get out of.”

Since the pandemic started, membership in QAnon Facebook groups has surged, often through this pipeline Facebook created. One prominent recruit is the woman dubbed “QAnon Karen,” who went viral after an anti-mask meltdown in a Target. As she later explained to NBC News, her QAnon journey started in new age wellness groups before the pandemic. Once she was bored in lockdown, content algorithms and pandemic-induced doomscrolling led her to the conspiracy. While Facebook announced in August that it would and remove 790 QAnon groups from the platform and limit the ability of its followers to organize , a month later the New York Times found that the conspiracy was still thriving on the platform. After the restrictions were announced, the newspaper tracked 100 still-active groups, finding that they were adding an average of 13,500 members a week. In some cases, the Times reported that Facebook algorithms continued to push users toward groups where the conspiracy was being discussed.

One of Jankowicz’s biggest fears about the upcoming election is the potential for groups to latch onto and share planted disinformation, whether from a Russian agent or someone creating chaos from within the US. “All they have to do is drop the link in a group,” she says. “Then Facebook’s ready made engagement mechanisms will drive that content, the more outrageous or outlandish it is.” Instead of having to purchase ads or create thousands of troll accounts to spread a message, now one person can drop an incendiary link in a Facebook group and the platform’s own algorithms will do the work of amplification.

This fall, Jankowicz is particularly worried that false news about voter suppression, mail-in ballots, and fraud will spread unchecked in groups. “People have been primed to listen to these narratives because of what the president has been saying,” she says, noting that she’s already observed misinformation about voting gain traction in groups. While Facebook has made a public commitment to remove misinformation about voting from its platform, this moderation often doesn’t reach into private groups. A Facebook spokesperson touted the company’s artificial intelligence as a tool to combat voting misinformation. “We’ve trained our systems to identify potentially violating content so we can remove it before anyone reports it,” the spokesperson said. “Once a piece of content has been fact-checked, our technology finds and labels identical content wherever it appears on the platform—including in private groups. We also continue to remove groups that violate our policies, including hundreds of QAnon and militia groups in the past month.”

Along with the threat of election disinformation comes the threat of violence, plotted online but carried out on in the real world. Ben Decker, the founder of Memetica, a digital investigations firm focussed on disinformation and extremism, fears that Facebook groups could become a place where people plan to bring weapons into the streets. “We don’t really use the term ‘lone wolf’ anymore,” he says. “We’re talking about stochastic terrorism, in that there is this random unauthored incitement to violence without explicit organization.” As Decker explains, the groups serve as forums where people put out calls to violence or echo calls for violence from figures like President Trump that someone may answer, though it’s unpredictable who. But those lone responders are finding each other online. “That stochastic threat is now becoming something that’s increasingly organized.”

What happened in Kenosha, Wisconsin last month is a prime example. Multiple groups used Facebook to coordinate bringing guns to a Black Lives Matter protest staged in response to the police shooting of Jacob Blake. A militia group called the Kenosha Guard used a Facebook event page to bring armed vigilantes to the protests on August 25. Meanwhile, a public Facebook group was created to encourage an armed response to the protests called “STAND UP KENOSHA!!!! TONIGHT WE COME TOGETHER.” According to the Atlantic Council’s digital forensic research lab, members of this group used it throughout the night to coordinate, posting many comments encouraging lethal force against protesters. One of the people drawn to Kenosha that night was Kyle Rittenhouse, a 17-year-old Trump supporter. He shot three BLM protesters, killing two.

Facebook has repeatedly shown that even when violence is being organized on its platform, it is ill-equipped to respond. The Kenosha Guard’s event page was public, allowing 455 people to report it to Facebook. Despite the complaints, the company’s moderators and algorithms repeatedly determined the page did not violate its policies. Facebook now says that it was a mistake to leave it up, blamed contracted moderators for the error, and said that militia groups are no longer allowed on the site, though many remain there. (This week, four people sued Facebook, saying it provided a platform for right-wing militias to plan to murder and terrorize protesters in Kenosha.) But even if Facebook improves its ability to respond to troublesome public events and groups, activity can quickly move to new groups. When Facebook removed QAnon groups, some sprouted up under new names, using slightly tweaked language to avoid detection.

Kenosha wasn’t the first time that Facebook has allowed armed protesters to organize on its platform. As early as 2015, Muslim Advocates, a civil rights non-profit, warned that Islamophobic groups were using Facebook event pages to stage armed rallies. In 2016, the group met with Facebook policy chief Monika Bickert and showed her images of gun-bearing demonstrators assembled outside of mosques who had organized using on Facebook event pages. Nothing changed, and in the following years the organization continued to see armed anti-Muslim groups organize on Facebook. “We’ve run into this problem again and again with Facebook, where they’ll point to some line or something in their very, very broad policies, saying like, ‘Oh, we prevent hate here’ or ‘We take action against bigots here,’” says Eric Naing, a spokesperson for the group. “But if you look at when the rubber meets the road, when Facebook actually is put into use by the public, it’s constantly being used to organize hate and violence.”

Facebook knew that groups were a problem even before it redesigned its systems to foreground them. In 2016, a company researcher found that extremist content was flourishing in a third of German political groups, most of them private, and that the groups were growing thanks to Facebook’s own recommendation algorithms. But rather than stop this trend, the next year they expanded on this model in the name of community and security.

In 2017, Facebook was used to organize the fatal white supremacist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, after which the company finally began to remove white hate groups. But many evaded removal, while others have cropped up undeterred. The boogaloo movement, which seeks to spark a civil war, thrived on the platform until this summer after federal prosecutors charged several members with crimes, including murder and plotting to use violence at a Black Lives Matter protest. In response, Facebook took down hundreds of affiliated groups, pages and accounts, although others have since risen to take their place.

Accustomed to a peaceful democratic process and transfer of power, it may seem alarmist to worry about chaos, armed riots, and mass disinformation this November. But the stage for disaster is set, not just by the radicalizing channels Facebook and other social media platforms provide, but by Trump and his Republican allies. Their message, coming with increasing frequency, is that if the president doesn’t win reelection it will have been stolen. “The only way we’re going to lose this election is if the election is rigged. Remember that,” Trump said in Wisconsin in August. “Be poll watchers when you go there,” he told a crowd in North Carolina earlier this month. “Watch all the thieving and stealing and robbing they do.” In a Fox News interview a few days later, Trump said people who would protest against him after the election are “insurrectionists” and endorsed lethal “retribution” against a figure in the Portland protests this summer, Michael Forest Reinoehl, who allegedly killed a far-right counter-protester.

This message has quickly filtered down to his allies. On Facebook live last week, Department of Health and Human Services spokesperson and Trump loyalist Michael Caputo warned Trump would win in November but that violence would ensue. “When Donald Trump refuses to stand down at the inauguration, the shooting will begin,” he said. “The drills that you’ve seen are nothing.” (Caputo’s rant prompted him to take a leave of absence from the agency.) The message from these examples and others is to prepare for violence.

Late last year, a bipartisan group concerned about Trump’s norm-breaking presidency formed the Transition Integrity Project. In June, they brought on experts in campaigns, polling, media, and government from both political parties to run through simulations of what might happen after the election. The group explored four potential outcomes: A Biden landslide, a narrow Biden win, Trump wins the electoral college but loses the popular vote, and a long period of uncertainty akin to 2000. The results were terrifying. “With the exception of the ‘big Biden win’ scenario, each of our exercises reached the brink of catastrophe, with massive disinformation campaigns, violence in the streets and a constitutional impasse,” wrote Rosa Brooks, one of the project’s co-founders and a law professor at Georgetown University, in the Washington Post this month.

The group’s findings put an emphasis on social media platforms, of which Facebook is by far the largest, and the importance of their moderation practices in the sensitive post-election period. “Social media in particular will undoubtedly play a heavy role in how the public perceives the outcome of the election,” the report states. “Political operatives, both domestic and foreign, will very likely attempt to use social media to sow discord and even move people to violence. Social media companies’ policy and enforcement decisions will be consequential.”

Last week, Facebook announced new measures to combat disinformation and violence, including changes to its group recommendation algorithm. The company says it will no longer recommend health-related groups, and that groups tied to violence—including QAnon and militia groups—will not only not be recommended, but will be removed from users’ search results and soon have less of their content presented in users’ news feeds. Facebook also says it will remove groups that repeatedly feature content violating company rules, and will not recommend groups that repeatedly share information judged false by Facebook’s fact-checking partners. While the promised steps could have an impact, Facebook’s struggles to stem the growth of QAnon over the past month demonstrate a limited ability to quickly and efficiently enforce new restrictions.

With voting already underway, experts fear the moves are too little and too late. Even with new limits on their reach, Facebook groups already serve as a robust and radicalizing infrastructure. Tweaks to the algorithms are ultimately small changes in an already dangerous ecosystem. “I’m just really not holding my breath for Facebook to change the infrastructure of how groups work ahead of the election,” says Jankowicz. Even if they wanted to, she says, “unfortunately, there’s not much time left, and these big changes on platforms of this size take a really long time.” Facebook has not indicated that it has any contingency plans in place should its platform, and groups in particular, become a hub for organizing violence and spreading disinformation after Election Day.

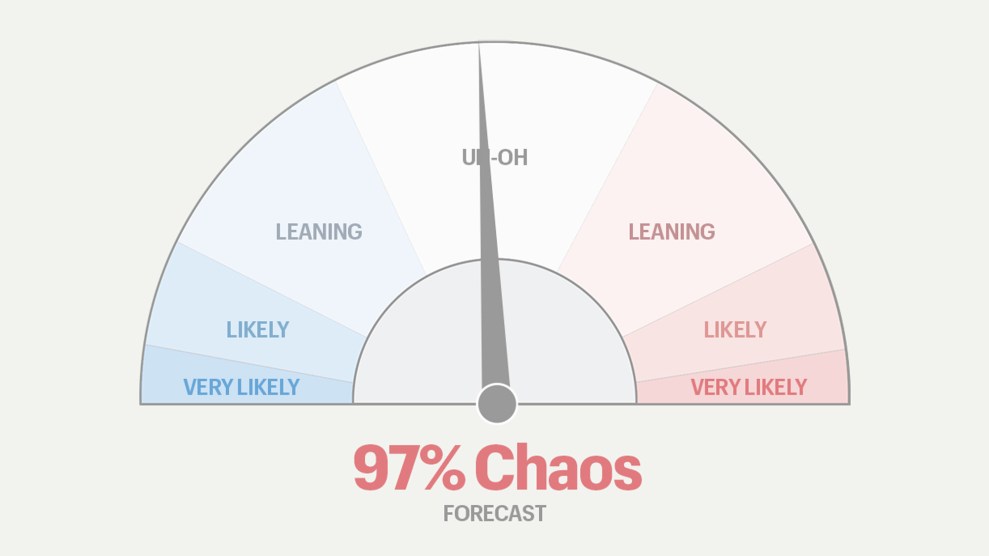

There are scenarios in which the outcome of the election is clear on election night. But Decker is thinking about what will happen in the more likely event that it takes days or weeks to count or recount decisive votes. “Who’s going to mobilize offline because of these group echo chambers, and how?” he wonders. “Facebook’s created an environment where this chaos theory can all play out.”