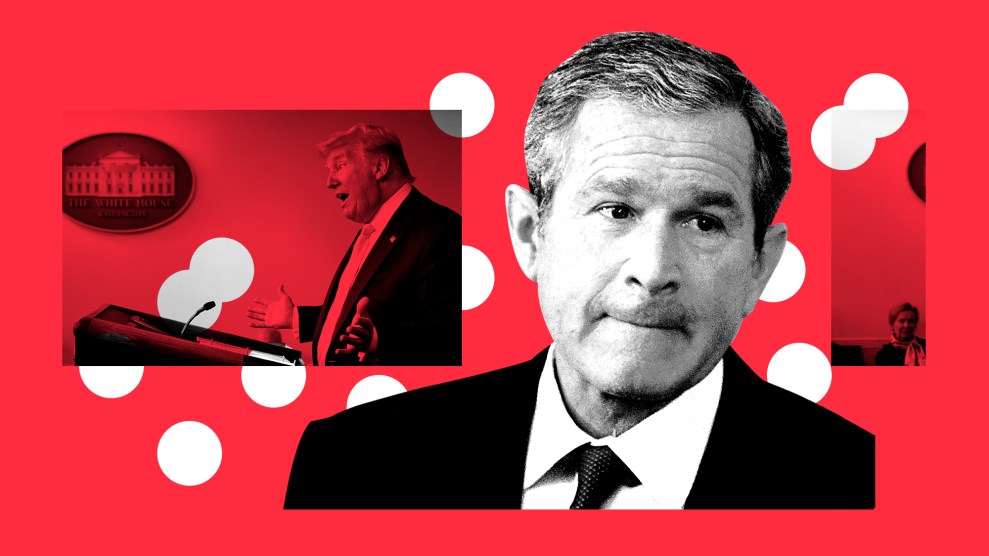

Mother Jones illustration; Michal Dolezal/CTK/AP; Evan Vucci/AP

The threat of a terrible disease loomed, and the race was on to vaccinate Americans. Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infection Diseases, warned that the Republican administration had to act responsibly and credibly. “The need to be forthcoming is of particular importance,” he cautioned. “Because the population feels powerless, it must rely heavily on the deliberations and decisions of government leaders.”

The year was 2002. The nation was reeling from the 9/11 attacks the year before, and the Bush administration sought to prove its mettle by rooting out the threats around the world. Most of us remember the fruitless search for weapons of mass destruction. Fewer recall another quixotic attempt to protect the nation against terrorism: the campaign to vaccinate Americans against smallpox, a disease that kills 30 percent of people who contract it. Early in 2002, the Bush administration identified a smallpox bioterror attack as a likely threat. Congress sent scientists into overdrive to revive a 40-year-old vaccine. The immunization was far from perfect: It could cause a fever in as many as a third of the people who got the shot and severe complications, like inflammation of the heart, in a much smaller number. One or two out of a million people would die.

Public health officials knew it would be a tough sell. Weighing the relatively small chance of a smallpox bioterror attack against the significant risks of the vaccine itself, an expert panel recommended that the president push to vaccinate only 500,000 frontline medical workers, rather than the entire American population. But the Bush administration defied that advice and aimed bigger: It announced a goal of vaccinating the half a million medical workers first, and eventually at least 10 million Americans from the general public. To reassure the nation about the safety of the vaccine, President George W. Bush took the first dose himself. “The president feels fine,” a White House spokeswoman triumphantly announced later that day. Administration officials believed that his example would be enough to convince Americans to get vaccinated in droves.

But as soon as the program launched, news of uncomfortable side effects began to spread. Many people who got the shot felt sick enough the next day that they had to miss work. Others had severe arm pain. “I just wanted to go to bed for a day or two there,” one 24-year-old graduate student who received the vaccine told the Washington Post. “I thought, ‘Can you just chop off my arm?'” These reactions came as a shock, the patients said: No one had warned them this could happen.

By 2004, just 39,213 first responders had been vaccinated—less than 10 percent of the president’s goal—along with a negligible share of the general public. The reasons for the underwhelming turnout, a 2005 report by the Institute of Medicine found, were failures of both leadership and communication. The president had ignored advice from the experts, and the White House never explained its recommendations. Rather, the government’s messaging around the vaccine was confusing and inconsistent. Officials never provided clear information on who was at greatest risk for severe reactions from the shot, what patients should do if a reaction occurred, or how individuals and families would be compensated if something went seriously wrong.

What’s more, the report found, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the agency tasked with implementing the vaccination plan and explaining it to the public, “seemed constrained by unknown external influences.” A later report elaborated that it “became apparent that security-related constraints were placed on CDC’s ability to communicate with key constituencies.” Some Americans came to believe that the vaccine program was a hasty political stunt performed by a president obsessed with proving to the nation that he had won the war on terror.

Sometime in the next year, when a COVID-19 vaccine becomes available, the government will roll out the largest immunization campaign in history. Public health officials fear that unless the Trump administration learns from those past mistakes, a similar scenario could unfold, but with far more dire consequences.

In July, a group of epidemiologists from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security published a report finding that Americans already see the COVID-19 vaccine project as a rush-job—part of a last-ditch effort by Trump to turn around his abysmal polling numbers before the election. In June, prominent vaccine scientist Paul Offit and bioethicist Ezekiel Emanuel wrote an op-ed in the New York Times titled “Could Trump Turn a Vaccine Into a Campaign Stunt?” The answer, the authors said, was yes, and they laid out a scenario in which Trump administration officials “badger the [Food and Drug Administration] to permit use of the vaccine” before scientists are certain it’s safe. “We must be on alert to prevent [Trump] from corrupting the rigorous assessment of safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines in order to pull an October vaccine surprise to try to win re-election,” they wrote. (Just this week, Russia hastily approved a new COVID-19 vaccine without proving its safety, raising concerns that President Vladimir Putin was making exactly the sort of political calculation that public health experts fear from Trump.)

But recent months have brought increased public pressure on the FDA to uphold safety standards, giving Offit and other public health experts more confidence that vaccines won’t be compromised. “The president would have a hard time circumventing those processes,” said Peter Hotez, a vaccinologist at Baylor College of Medicine. “The scientific community has a much bigger voice now than we’ve had in the past, especially on the cable news networks and in the media.” Last week, Sens. Maggie Hassan (D-N.H.), Mike Braun (R-Ind.), and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska) introduced legislation that it would require pharmaceutical companies and the federal government to share more data about vaccines’ safety and efficacy. Saad Omer, a Yale University epidemiologist and expert on vaccine safety, said he found the increasing calls for transparency “reassuring.”

The American public, however, is a different story. The damage to public trust in the COVID-19 vaccine may already be done. A Gallup poll last week found that Americans are so worried about the safety of the coronavirus vaccine that one in three plan not to get it. In an AP poll in May, half of respondents said they planned to forgo the shot. Offit believes that the language the White House has used to describe the vaccine development process is partly to blame. “The race for a vaccine, ‘Operation Warp Speed’—it does feel like it’s being done in a rushed manner that doesn’t allow you to do what you would normally do, which actually isn’t true,” he said. Hotez, who wrote a book about the damaging campaigns mounted by vaccine skeptics, said he has watched in horror as more Americans have expressed doubts about vaccines in recent months. He worries that the anti-vaccination movement could move from the fringe to the mainstream. “Rather than it going into retreat with COVID-19, as one might expect, it’s actually been enabled by the lack of communication, or miscommunication, coming out of the White House,” he said.

If public wariness of COVID-19 vaccines persists, it won’t matter how safe and effective the shots are—the project of vaccinating Americans could fail as miserably as the smallpox campaign did, only this time on a much grander scale. In order to avoid repeating those missteps, the government will have to level with Americans. The experts I spoke to all agreed that messaging must begin before a COVID-19 vaccine is approved. A first step, said Omer, might be for public health officials to describe exactly how vaccine developers can speed up the process without compromising safety. Americans should know, for example, that COVID-19 vaccine candidates will go through the same, three-phase trial process as any other vaccine.

The messengers of vaccine information may be as important as the message itself. Because evidence suggests that most Americans trust their doctors, physicians will likely play a key role in disseminating vaccine information. In its guidelines for communicating about vaccine safety, the World Health Organization recommends that doctors “be well informed and confident in their own minds about these issues” so they can clearly explain the risks and benefits to their patients. A recent report on COVID-19 vaccine communication from the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security emphasized that doctors and public health officials will also have to tailor their messages to the communities they serve. For example, while African Americans have suffered disproportionately from COVID-19, the AP poll found that just a quarter of Black Americans would trust a vaccine.

The worst thing the White House could do, Hotez said, would be to overstate the effectiveness of the vaccine. That’s because, at least at first, it probably won’t be a silver bullet. “People like [White House trade adviser] Peter Navarro always tend to veer towards magical thinking—we’re going to hydroxychloroquine our way out of it, or we’ll vaccinate our way out of it—and that’s not the way it works,” said Hotez. Rather, the first vaccines will be more like an additional layer of protection: We’ll likely still have to wear masks and avoid crowds. Offit, who believes the first vaccines probably won’t be more than 75 percent effective, worries that “people will get the vaccine and think ‘great, I don’t need to wear a mask,’ when they probably still do.” Omer, who is more bullish on the prospect of life returning to normal after a vaccine, warns that even if the vaccine itself is highly effective, distribution will take months, maybe longer. “Even with a solid vaccine, we’d have to keep some measures in place during that period,” he said.

In a 2002 commentary on the smallpox vaccination campaign in the New England Journal of Medicine, Fauci wrote, “The general public must understand the decision-making process as well as the rationale behind decisions that may affect their health and their lives.” Of all the advice that Fauci has offered the White House over the years, this 18-year-old pearl might be the most important. Let’s hope that this time around, someone listens.