Like many people, Minu Aghevli watched January’s impeachment proceedings in horror. It wasn’t just because she was outraged that Donald Trump had abused the power of his office. Nor was it because she thought Trump was the victim of a nasty partisan “witch hunt,” as he loves to put it. What shook her was how the intelligence community whistleblower—whose complaint kickstarted the whole impeachment process—was being treated.

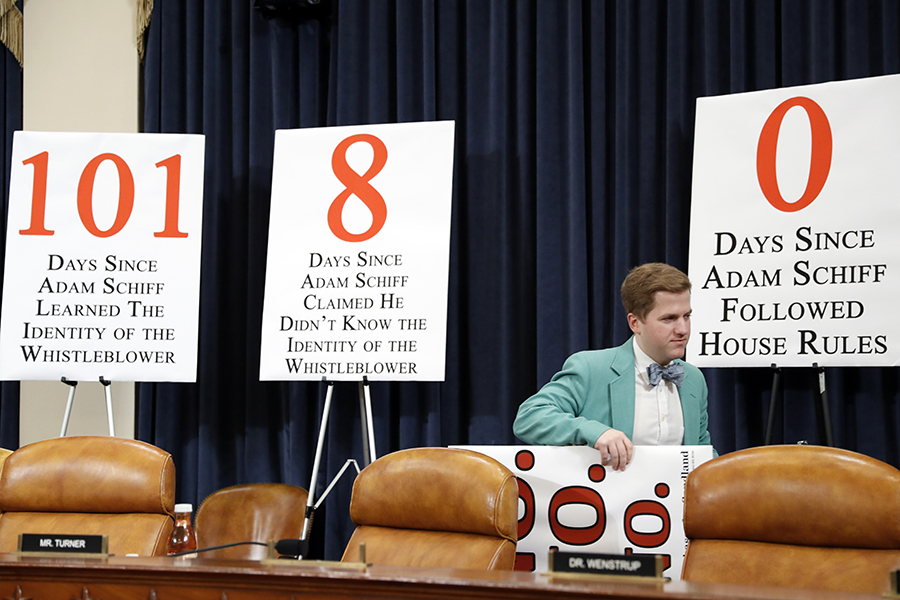

In hundreds of statements about the whistleblower—from bullying tweets to negative comments made to reporters—Trump didn’t just publicly question the person’s motives and dispute their account; he threatened retaliation and called for the person’s identity to be revealed. Several Republican members of Congress also claimed to know the whistleblower’s identity and repeatedly tried to name them. When the House Intelligence Committee released its official impeachment inquiry report, it offered a particularly grim summary: “Most chillingly, the President issued a threat against the whistleblower and those who provided information to the whistleblower regarding the President’s misconduct, suggesting that they could face the death penalty for treason.”

Aghevli, herself a federal whistleblower, felt sick watching all this play out on such a public scale. “It made me cry,” she tells me with a quiver in her voice. “Because I felt like, ‘Oh God, I know exactly what that feels like.’”

Andrew Harnik/AP

That feeling would only get worse for Aghevli—and for the thousands of public servants who report misconduct in the federal government each year. In the months since the Senate acquitted Trump of two impeachment charges, the president has declared an all-out assault on whistleblowing. Beginning in April, the president dismissed inspectors general—the very people whistleblowers can confidentially turn to in order to report corruption, waste, and abuse of power—in five different departments in the span of just six weeks, starting with Michael Atkinson, the intelligence community inspector general who alerted Congress to the whistleblower complaint about Trump’s Ukraine phone call.

In the midst of this IG firing spree, Aghevli sent me a panicked email late one night: “It’s hard to express how depressing and scary it is to be required to do your annual Whistleblower Protection and Accountability training while the president is firing the IG for taking a report from a whistleblower and the Secretary of the Navy is essentially threatening the sailors of a ship and publicly disparaging their captain who was fired for reporting a health crisis.”

“It’s literally the definition of gaslighting,” she added.

Aghevli spent nearly two decades as a Department of Veterans Affairs clinical psychologist at an opioid treatment program in Baltimore before she blew the whistle in 2014 on a program manipulating wait lists to reduce the number of patients being treated. She thought filing a whistleblower complaint would solve the problem, but it only made her life worse over the years. She received intimidating emails from superiors urging her to keep quiet. Coworkers treated her like a traitor. Her superiors barred her from seeing patients, some of whom she’d treated for 15 years. Eventually, in early 2019, she was reassigned to menial administrative work at a front desk. Then, on June 24 last year, the day before she was set to testify before the House Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, the VA sent her a letter threatening to fire her.

While VA whistleblowers in particular have long faced a culture of retaliation and intimidation—it was an issue that notoriously plagued the Obama administration—it has dramatically worsened in the Trump era. Since Trump took office, the climate for whistleblowing at the VA and across the federal government has never been worse. Federal workers who want to report wrongdoing or corruption in their workplace don’t just risk becoming a professional pariah like Aghevli, but can be turned into pawns in a hyper-partisan political landscape. Retaliatory actions against whistleblowers are increasingly common and GOP lawmakers threaten to dox and punish these public servants for exposing corruption. And it’s all legal thanks to the weak federal whistleblowing laws that the Trump administration has skillfully exploited.

The danger extends far beyond the well-known names most people associate with whistleblowing, the civil servants who sounded the alarm on large matters of national security—the Ukraine whistleblower, National Security Agency executive Thomas Drake, who was prosecuted during the Obama administration, or Edward Snowden, who leaked thousands of pages of classified NSA documents. The reality is that most whistleblowing is far more quotidian, often pertaining to small-scale good governance that doesn’t make headlines. Between 2014 and 2018, more than 14,000 federal employees filed whistleblower disclosures or retaliation complaints, according to data compiled by the Government Accountability Office. And while advocates were outraged by the treatment of the intelligence officer in the Ukraine matter, they’re more concerned about the atmosphere of rank-and-file corruption that has flourished within the Trump administration and the less obvious attacks on the system, and how the current political atmosphere might impede the sort of whistleblowing that is required for competent government. The same month as the House impeachment proceedings concluded, a poll conducted by the Government Business Council, the research arm of Government Executive, revealed that one in three federal workers are now less likely to report wrongdoing in their workplace after attacks by the president and his allies on the Ukraine whistleblower.

“On paper, the United States has some of the strongest whistleblower laws around,” says Mark Zaid, an attorney who represented the Ukraine whistleblower. “But they just don’t work, because the policies aren’t implemented properly.”

Consider the fate of the Merit Systems Protection Board, a small agency where federal workers who believe they have been unjustly disciplined or fired can appeal—at least in theory. In practice, it has lost all its ability to address federal whistleblower and retaliation complaints. It has lacked a quorum for the entirety of Trump’s tenure, and since February 2019, it hasn’t had a single member sitting on its board; meanwhile, it has a backlog of nearly 3,000 cases waiting in limbo. It’s a “disastrous situation” for whistleblowers who face retaliation, says Liz Hempowicz, the director of public policy at the nonpartisan Project on Government Oversight.

This dismantling of whistleblower protections is culminating at a dire time, when the Trump administration scrambles to dig the country out of the biggest economic recession since the Great Depression, and as the $3 trillion allocated by Congress to help the country fight the coronavirus pandemic trickles out to local and state governments and countless private companies. But anyone who wants to blow the whistle on fraud, waste, or corruption has essentially no protections. Rick Bright, the former head of the US office tasked with developing a coronavirus vaccine, is one early casualty of the system’s failure. In a whistleblower complaint in May, he alleged that he was booted from his position after his warnings about the seriousness of the virus were ignored, as well as his concerns about the potential harm of hydroxychloroquine, Trump’s preferred drug to treat COVID-19. Bright was essentially demoted and his reputation was tarred by the president and his allies.

“Right now I think it is completely unreasonable to expect any whistleblower to go to any inspector general office within the federal government,” Hempowicz says. “Because there’s no guarantee that the president won’t replace that inspector general with another political appointee whose loyalty is to the administration rather than to the administration of the law.”

Zaid echoes Hempowicz’s concerns: “I don’t think there’s any way that people cannot look at where we are in 2020, and not believe that people would be deterred from coming forward.”

In many ways, the VA under Trump is a perfect microcosm of how oversight in his administration works: Don’t just discourage people from speaking out; make it so their lives will be hell if they do.

It didn’t always seem like it’d be that way. In April 2017, Trump signed an executive order to establish an office to help protect whistleblowers at the Department of Veterans Affairs, which had been plagued by scandals and corruption for years. Months later, the Office of Accountability and Whistleblower Protection (OAWP) became permanent law after it passed through Congress with overwhelming bipartisan support—a moment that offered some hope early in Trump’s tenure that despite the conflicts of interest presented by the president, perhaps his administration could work across the aisle to pass laws to stamp out corruption and mismanagement.

Whistleblowing, after all, has a long history of bringing lawmakers together. Ever since the Revolutionary War, when 10 American naval officers reported on their commodore torturing captured British soldiers, Congress has recognized that protecting the rights of whistleblowers is the best defense against corruption. That episode led to the world’s first whistleblower protection law, which was passed on July 30, 1778—two years after the Declaration of Independence was signed. Since then, Republicans and Democrats have traditionally been united in the idea that protecting whistleblowers is “critical to keeping our democracy alive,” explains Allison Stanger, a professor at Middlebury College and author of the book Whistleblowers: Honesty in America from Washington to Trump. The Whistleblower Protection Act, which passed through Congress with overwhelming bipartisan support in 1989, set up modern whistleblowing laws, granting several federal offices with the authority to properly investigate any disclosures while protecting the employees who filed them. In 2012, Barack Obama signed the Whistleblower Protection Enhancement Act into law, which added more protections from retaliation for federal whistleblowers. It had passed Congress with unanimous consent.

“It’s really a democracy preserving system, consistent with the Constitution,” Stanger says of modern whistleblowing laws. “It’s specifically rooted in law, and it’s something that both Republicans and Democrats alike, until very recently, supported.”

That changed with Trump. While his allies like Rep. Devin Nunes (R-Calif.) and his current chief of staff, former Rep. Mark Meadows (R-N.C.), have long records of supporting whistleblower laws and federal whistleblowers, they have been some of the people most vociferously attacking the Ukraine whistleblower. “If I had a degree of certainty who the whistleblower is, I promise you I would tell you,” Meadows told reporters in October amid the House’s impeachment inquiry hearings.

“This administration has brought the worst out in people at so many different levels,” Zaid says.

Jay DeNofrio, an Obama-era whistleblower at the VA, has been similarly disillusioned by how Trump and allies have worked to silence his peers. Like that of Aghevli, DeNofrio’s experience was maddening and isolating. In 2013, while working as an administrative officer at a VA hospital in Pennsylvania, he suspected that a doctor he had a close working relationship with was suffering from dementia. The last thing he wanted was to get anyone in trouble, but he noticed severe peculiarities—the doctor would forget recent conversations, or the names of employees he had worked with for years. There were complaints about the doctor forgetting to ask about patients’ medical histories, performing invasive exams without gloves, and giving out severely false medical advice, including a near-fatal episode in which he allegedly sent a patient with double pneumonia home with only the instruction that the patient’s spouse massage their ribs as a treatment. DeNofrio reported his concerns to the hospital’s director and chief of staff in a letter. Since another doctor at the hospital attached his name to the letter as well, DeNofrio expected that the hospital would act accordingly and take the doctor off duty to protect patients from more potentially fatal errors. Instead, the hospital ignored DeNofrio’s warnings for months. Finally, the hospital’s leadership gave in to his concerns and agreed to administer a cognitive test—which was later determined to be faulty. The doctor passed and the hospital’s administrators warned DeNofrio to “no longer report concerns related to impairment.”

DeNofrio continued to sound the alarm for two years, going up the chain until it came to the attention, in 2015, of the US Office of Special Counsel—the federal watchdog agency charged with protecting whistleblowers and investigating their claims. All the while, DeNofrio says the leadership of the Altoona VA kept trying to silence him. He claims they’ve retaliated against him through denied promotions, low job performance ratings, denied overtime pay, and threats of dismissal. “I didn’t fully think of it as whistleblowing,” DeNofrio says. “I was just trying to keep patients safe.”

DeNofrio was able to find solace by connecting with other VA whistleblowers, like Aghevli, through a group called the VA Truth Tellers that formed in 2015 as a way to help connect whistleblowers with resources, educate them on their rights, and advocate for stronger protections. Eventually, he became one of the group’s strongest advocates, helping guide other potential whistleblowers through the process. “I would tell them to do what’s right,” DeNofrio says. “That’s the hardest part; it’s trying to show people that you’re going to face retaliation, but I stress that the strongest right you have as a whistleblower is your First Amendment right.”

But as Trump and his allies took control of the VA—both in official leadership and in more behind-the-scenes maneuverings—DeNofrio discovered that the new law meant to protect VA whistleblowers had been manipulated into a tool for the agency’s leadership to single out and impose even more retaliations against whistleblowers. Peter O’Rourke, a Trump loyalist and veteran with experience in government consulting, was appointed the first director of the Office of Accountability and Whistleblower Protection (OAWP). This new office was supposed to offer whistleblowers a direct line to report mismanagement and wrongdoing to an independent office whose sole purpose was to investigate these claims, rather than reporting them directly to their supervisors. Trump said the office would be one of the “crown jewels” of his administration.

Instead, O’Rourke, the very person charged with safeguarding whistleblowers, used his position to retaliate against them, according a blistering report released late last year by the agency’s inspector general. “OAWP leaders made avoidable mistakes early in its development that created an office culture that was sometimes alienating to the very individuals it was meant to protect,” the report states.

Even though both Aghevli and DeNofrio became whistleblowers in the previous administration, they say that because they’d been so public about their experiences, they were targeted by the new office as problematic employees. In one instance, on the eve of the annual Whistleblower Summit on Capitol Hill in 2017, where DeNofrio was scheduled to speak, he says a group of whistleblower attorneys in DC called him with a warning: “They said Peter O’Rourke said that if you come to this summit, he’s going to go to the Republicans on the Hill and tell them to shut it down for the entire whistleblowers summit.”

Not long after the OAWP formed, DeNofrio began hearing that many of the whistleblowers in the Truth Tellers group were increasingly being threatened and fired. “If someone had an issue, they would call one of us in this group and we would get them an attorney, or help them with an administrative investigation, or get them with a reporter, whatever they needed,” DeNofrio says. “Before Trump, you could do this and you weren’t going to get fired.”

The inspector general report confirmed what DeNofrio had heard from the Truth Tellers, and in turn eviscerated O’Rourke’s leadership. The IG found that the office was only willing to open cases if a whistleblower was willing to reveal their identity—effectively discouraging people who feared reprisal. Meanwhile, some individuals who attempted to raise concerns about management ended up becoming the target of a probe by the office. O’Rourke and other OAWP officials also “made comments and took actions that reflected a lack of respect for individuals they deemed ‘career’ whistleblowers,” like DeNofrio and Aghevli. One troubling instance in the report “involved the OAWP initiating an investigation that could itself be considered retaliatory”: At the behest of a senior official with social ties to O’Rourke, the office investigated a whistleblower who had filed a complaint against the senior leader. After a brief investigation, the OAWP substantiated the senior leader’s allegations without even interviewing the whistleblower.

O’Rourke was forced out in December 2018, but his ouster didn’t change much. Tamara Bonzanto, who took over the OAWP in January 2019, promised during multiple Senate confirmation hearings to turn around the problems that plagued the department, but a POGO investigation released this March found many of the same issues still festering in the VA. “Employees of the accountability office say it is beyond dysfunctional and that people are ‘terrified’ now that efforts to reach out to Congress and communicate with higher-ups in the department have failed to keep the office’s leaders in check,” the report says.

Brandon Coleman, a high-profile former VA whistleblower who was tapped by O’Rourke to work in the OAWP—initially seen by many as another promising sign that the Trump administration would be friendly toward whistleblowers—has gone on the record about how bad the OAWP became. He filed a complaint last summer, which was also sent to members of Congress, that described the work environment as “toxic” and called the office a “dumpster fire.” Coleman said he and other colleagues in the OAWP had been shut out of important meetings and worried they’d be demoted for speaking out. Last spring, the OAWP even shut down Coleman’s whistleblowing mentorship program, which he had established as a way to help victims of retaliation in the VA. “How can you treat your employees the exact way we’re trying to protect employees from being treated?” Coleman told USA Today.

DeNofrio still works at the VA, though he was recently demoted to a teleworking position. He believes the only reason he hasn’t been fired in the past three years is because of how public he’s been about his whistleblowing—though the OAWP has tried. According to internal OAWP communications that DeNofrio obtained through the Freedom of Information Act and subsequently shared with Mother Jones, investigators in the office interviewed his coworkers and encouraged them to immediately document and report “any instances of poor behavior” by DeNofrio, stating that just because he was a protected whistleblower doesn’t mean he gets to “walk on water.”

Despite the current circumstances, he’s still managed to maintain a loose network of VA whistleblowers who are able to give advice, offer connections to legal support, and provide other resources to potential whistleblowers, albeit much more discreetly than when he was with the Truth Tellers, which essentially disbanded after the failures of the OAWP became apparent. But everything that happened with the Ukraine whistleblower, he says, has spooked some of the people he’s connected with recently.

“Everybody’s scared to death of saying anything,” he says, “which is bad during a pandemic.”

Still, people are saying something: As of July 28, the Office of the Special Council recorded that 73 whistleblower disclosures related to the pandemic have been filed. There’s also been “92 complaints of prohibited personnel practices related to COVID-19,” a spokesperson for the agency tells me in an email. But the risk remains immense. At least 15 of those whistleblowers have filed complaints alleging that they’ve been retaliated against for raising concerns.

“We’re entering a highly unstable period in our history with the public health crisis and economic crisis on top of that,” says John Kostyack, who heads the National Whistleblower Center, a nonprofit organization that connects whistleblowers with legal assistance and advocates for stronger whistleblower protection laws. “We think that the need for whistleblowers is going to grow and the obvious benefit that they deliver will become even more obvious.”

COVID-19 continues to paralyze the country in ways we could never have imagined, and the federal and state response to mitigate the effects of the pandemic has opened up mountains of opportunities for malpractice and corruption. It’s already clear how critical the ability for whistleblowers to act without fear of reprisal is in this moment. Back in February, one senior official with the Department of Health and Human Services raised alarm that the workers receiving the first Americans evacuated from Wuhan, China, did so without proper training or protective gear. And in early April, Christi Grimm, then the acting top watchdog for HSS, signed off on a report that said that the nation’s hospitals were struggling to combat COVID-19. Days later she was criticized by the president, and on May 1, she was ousted when Trump nominated a permanent inspector general to replace Grimm, who had held the position on an acting basis since January. Then, later this spring, Trump also fired Glenn Fine, who had been the Defense Department’s acting IG since early 2016 and was briefly appointed to lead a watchdog panel overseeing the White House’s coronavirus economic relief. Fine hadn’t even been given the chance to begin an investigation.

One of the biggest challenges to pandemic oversight, according to Stephen Kohn, a whistleblower lawyer who also works with the National Whistleblower Center, is finding ways to both encourage whistleblowers to come forward and protect them when they do—and not just ones working for the federal government.

Flaws in whistleblowing laws make it harder for nonfederal workers to flag corruption or negligence, which Kohn says is particularly crucial as certain front-line sectors are being rushed back to work despite hazardous conditions. One particular area of concern is in the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA)—the federal agency where these workers can alert the government about fraud and corruption in private corporate action. Kohn explains that OSHA’s whistleblowing laws essentially stymie any worker who files a complaint alleging that their employer broke the law because it creates a “legal mechanism” in which Trump runs the show with no judicial appeal. In other words, any worker who files an OSHA whistleblower retaliation complaint cannot take that complaint to court; it’s up to government officials in the Department of Labor, which houses OSHA, to determine if the complaint has merit. Kohn says it’s an outdated law that he fears Trump administration officials will exploit to reinforce the president’s desire to reopen the country and send people back to work, even if it’s not safe to do so. “If Trump decides that it’s time to return people to work, he can literally give every single business in this damn country a pass, and that puts workers in the same position that these national security whistleblowers found themselves in,” Kohn says.

That puts essential workers, such as health care professionals, at particular risk for reporting wrongdoing. There’s already been a number of health care first responders who have come forward to expose a wide variety of issues in hospitals struggling to fight COVID-19: an appalling lack of N95 masks and personal protective equipment; nurses in New York City hired from out of state and placed in units where they have no experience; and too many cases of workers fired for speaking out against dangerous conditions that unnecessarily put themselves at risk.

The medical field is far from the only industry flooding OSHA with whistleblower complaints; at a House hearing in May, it was revealed that OSHA has already received nearly 5,000 complaints related to COVID-19, and it’s taken enforcement action in only one of those cases.

“We want to believe that the world is basically fair,” Aghevli says. “So the deeper we sink into this climate of intimidation and unethical behavior, the harder it will be for people to keep a clear head and change course.”

There’s no better example of Aghevli’s theory than the plight of Rick Bright, the vaccine expert and HHS whistleblower. In late June, Bright filed an update to his original whistleblower complaint, alleging that since he was ousted from his role in overseeing the federal development of a COVID-19 vaccine in April, HHS Secretary Alex Azar has been “on the war path” to punish him. The complaint alleges that Bright was reassigned to the National Institutes of Health, where he was supposed to be working on coronavirus testing, but his role had been essentially confined to “making contracts with diagnostics companies.” Azar also allegedly told HHS employees to “refrain from doing anything that would help Dr. Bright be successful in his new role,” according to the complaint.

It’s all because Bright dared to cross Trump in his attempt to push hydroxychloroquine as a potential treatment for the coronavirus. Since news of Bright’s whistleblower complaint broke, Trump has used the same playbook that he did for the Ukraine whistleblower: Disparage and discredit. In comments to reporters and on Twitter, both Trump and Azar painted Bright as a “disgruntled employee,” who was unfit for his job and just collecting a paycheck. “I don’t know the so-called Whistleblower Rick Bright, never met him or even heard of him,” Trump tweeted, “but to me he is a disgruntled employee, not liked or respected by people I spoke to and who, with his attitude, should no longer be working for our government!”

“When you see that kind of conversion from the idea that whistleblowers are something that helps keep us on the rails to the rhetoric that they’re an enemy of the people, you’re saying that it’s all political,” Stanger says. “And that’s how democracies die.”

Image credit: Mother Jones illustration; Drew Angerer/Getty