The transformation from fowl to meat begins with carbon dioxide. The gas knocks the turkeys out; a blade finishes the job. It’s all surprisingly clean, down to the vacuums that suck out their lungs. Stripped of organs and feathers, the line of identical denuded carcasses splashes into a cooling bath.

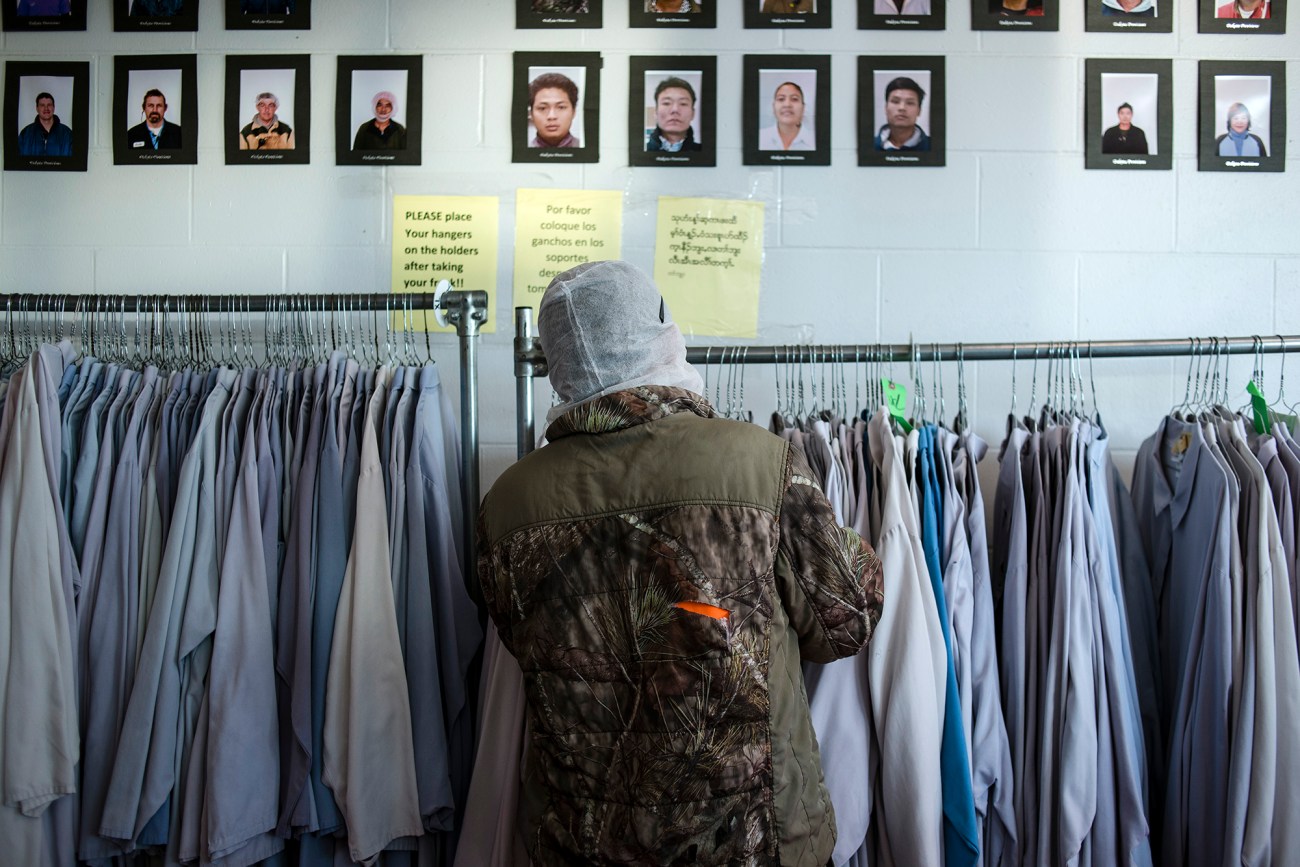

The work is monotonous, but the workers are markedly diverse. They hail from Brazil, China, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, India, Nepal, South Korea, Vietnam, Puerto Rico, and the Micronesian archipelago of Chuuk. But most of the 1,200 employees are Karen, members of an ethnic group from Myanmar (historically known as Burma) whose families came to the United States as refugees. Their presence in Huron, South Dakota, 8,000 miles from their homeland, is an accident of history that has revived a dying city.

Just before the turkey plant opened in 2005, about 97 percent of kids in Huron schools were white. Today, just over a third of kindergartners and first graders are white. In 2018, the Huron area took in more people from abroad and Puerto Rico, as a share of its 18,800-strong population, than any other place in the United States. In less than 15 years, the community has gone through a demographic transformation that usually takes generations.

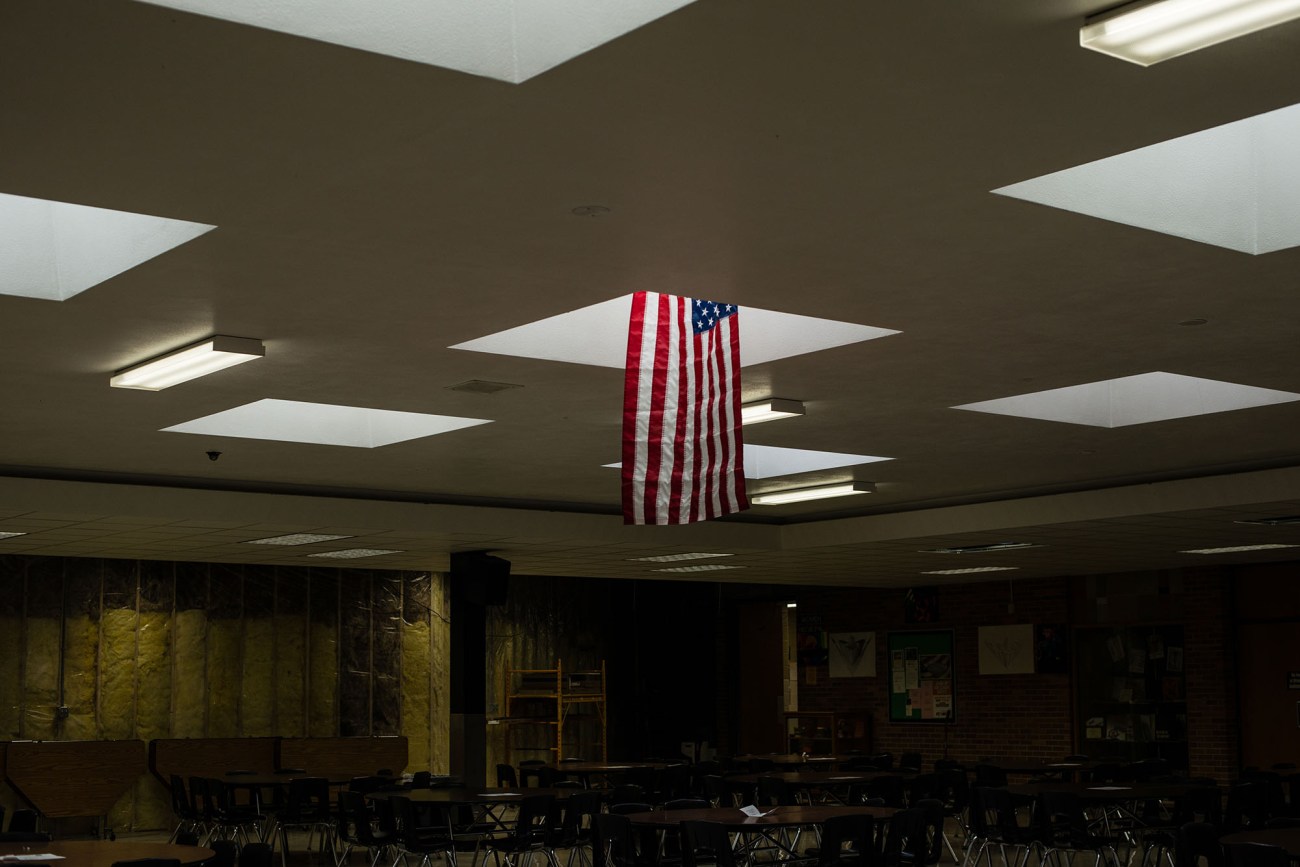

This is the story of how Huron—the only sizable town in Beadle County, which Donald Trump carried by 37 points in 2016—became not only a magnet for immigrants but a place where they are celebrated. It’s the story of how the deepening divide over immigration can break down when newcomers are neighbors, not abstractions—and how a small town in a red state embraced change when the alternative was decline and decay.

It’s also a complicated story. More than half of frontline meatpackers are immigrants, according to a Center for Economic and Policy Research analysis, and roughly 80 percent are people of color. Relatively few US-born white people take notoriously grueling jobs in an industry where the average wage is about $14 an hour. For hundreds of first-generation Karen Americans, whose job prospects were often limited by not speaking English, the turkey plant was the best option available. It was that reality that made Huron’s recovery possible.

But its success was neither immediate nor inevitable: The first Karen (kuh-REN) refugees were greeted with wariness, sometimes hostility. But city leaders were determined to overcome it. Immigrants and their supporters spoke to churches and clubs to explain how Karen people had been forced out of their homeland. They patiently answered questions, even the ones about whether the newcomers would eat their neighbors’ dogs. The superintendent restructured the school system to make segregation impossible. Huron’s experience provides lessons for the nation, although most Huronites are happy to stay out of the spotlight.

That reticence was on display in November 2018, when President Trump pardoned two Thanksgiving turkeys, named Peas and Carrots. They’d come from Dakota Provisions, whose chairperson stood alongside the president in the Rose Garden. “Love South Dakota,” Trump said about the state where a crowd at one of his appearances had recently chanted “Build the wall!”

No one mentioned the plants where the rescued turkeys had nearly met their end, or the immigrants who would have slaughtered and processed them. Huron, a town that quietly undercuts so much of the narrative about immigration, was invisible.

Until suddenly it wasn’t. Two months after I visited in January, Huron made news as South Dakota’s first COVID-19 hotspot. As the virus spread through the Dakota Provisions workforce and the local Karen population, it laid bare the inequities that had always lurked behind Huron’s immigrant-led revival.

Huron’s claims to fame are the state fair it hosts each September and the world’s largest pheasant sculpture (28 feet high, made from 22 tons of steel and fiberglass). Local heroes include Cheryl Ladd, who went on to play one of Charlie’s Angels, and Hubert Humphrey, who worked at his dad’s drug store on Huron’s main drag before becoming a Minnesota senator and vice president. But Huron is not white Americana in amber: Alongside the old mom-and-pop standbys are new Asian and Latino churches, restaurants, and grocery stores providing a new sense of vitality.

Huron’s status as a meatpacking town began to change when the Armour plant shut down in 1983 after workers rejected a pay cut. Paul Aylward, who served as Huron’s mayor until June, remembers being shocked at his first paycheck when he started working at the plant in 1968. At about $120 for the week, it was similar to what he’d been making each month in the military. By the time the unionized plant closed, Aylward was earning nearly $30 an hour in today’s money. He’d go on to lead the state’s AFL-CIO, but the era of high union wages in meatpacking was fading away.

Huron lost another meatpacking plant in 1990 and then another seven years later. The day of the 1997 closure of a hog slaughtering operation that employed 850 people became known as Black Thursday. The town’s population declined from around 14,000 in 1970 to less than 12,000 in 2005. The school system, which once had about 200 students per grade, now had barely 100 in the lower grades.

Huron’s revival began with the Hutterites, an Anabaptist group that shares roots with the Mennonites and the Amish and whose members live in isolated communities, called colonies, across South Dakota. Many Hutterites, who speak a language derived from 18th-century German dialects, are turkey farmers. Rather than send their turkeys to be slaughtered out of state, 44 colonies came together to form Dakota Provisions. In 2004, the new company announced that it would build a plant in Huron that would employ up to 1,000 people. A headline in the Sioux Falls Argus Leader summed up the importance of the news: “Huron: from Gloom to Boom.”

The challenge was how to get people to work in Huron, which is a 120-mile drive from the nearest major airport, in Sioux Falls. The task fell to Dakota Provisions’ human resources director, a Huron native named Mark Heuston, whom everyone calls Smoky. A white-bearded bear of a man—the pelt of an actual black bear he shot is splayed across the wall of his office—Smoky resembles a muscled Santa Claus, a role he has sometimes filled at local Christmas events.

Smoky had experience with refugees from Southeast Asia; he’d worked with Hmong people from Laos at a meatpacking plant in Wisconsin. When it came to finding out about the Karen, he said, “Truthfully, I got lucky.” He knew that the Twin Cities had among the country’s largest Hmong populations. So in 2007, as he struggled to find enough workers around Huron, he went to Minnesota to recruit at a Hmong community center.

“When I was interviewing individuals, I kept walking by this one room with 40, 50 people in it,” Smoky recalled. The people showing Smoky around said not to bother with the people in the room, who were Karen ESL students, since he was there to recruit Hmong workers. “I don’t care what nationality they are,” Smoky told them. He knew nothing about the Karen, but it didn’t matter. If they wanted a job, there was one waiting for them in Huron.

Tha Gerh “Tiger” Paw, her six siblings, and their parents were the first Karen family Smoky recruited to live in Huron. In 2005, they’d migrated from Bangkok to St. Paul after fleeing what was then the world’s longest-running civil war. During World War II, the Karen, some of whom had converted to Christianity, fought alongside the British against the Japanese and Burma’s Bamar ethnic majority. British officers promised Karen soldiers a nation of their own after the war. Instead, the British government established a united Burma in 1948, and civil war broke out. Of the roughly 5 million Karen in Burma, hundreds of thousands fled the Burmese military’s attacks into the jungle and across the border into Thailand. By the late 1990s, nearly 100,000 were living in refugee camps in Thailand.

Paw, now an employee of the South Dakota Department of Labor, was about 8 and hiding with her family in the Burmese jungle when soldiers surrounded their village. “We’re going to run,” her father told her. The troops opened fire, killing a blind elderly woman. A friend of Paw’s father was shot in the neck, and as he bled out, he told her to leave him behind.

Her family, mostly barefoot, managed to escape over a mountain. When her two teenage sisters became ill, her dad carried them. They walked for two and a half days without food before reaching a village. Eventually, they made it to Bangkok, where they would spend five years waiting for the US government to vet their application to resettle here as refugees.

When Paw came to Minnesota as a 15-year-old in 2005, she knew essentially no English. She assumed Huron would be as diverse as the Twin Cities but found that she was the only Karen student at the high school. Her dad helped recruit some Karen friends from Minnesota to join him. Those friends brought their friends. Lah Maypaw Soe, founder of Huron’s Karen Association, puts the size of the town’s Karen population now at about 2,500.

On Soe’s first day in Huron in 2009, she and her three kids played outside, devouring the snow she’d dreamed of seeing while growing up in a Thai refugee camp. A white woman who was driving by yelled at them to stop eating it.

In refugee orientation sessions in Thailand, Soe had been told that some Americans wouldn’t welcome them and that she should respond with patience and kindness. She didn’t know what her neighbors meant when they said “fuck you,” so she initially replied with a polite “thank you.” When she got a job as a caseworker at Lutheran Social Services, someone left a note on the office door threatening to cut off her leg if Karen people kept coming to town.

Rather than withdraw, she tried to educate her neighbors. After many nights spent learning English, she began a campaign to explain what had driven Karen people to the United States. She spoke to anyone who would listen—the Lions Club, local Democratic and Republican groups, church ladies—and answered all their questions. Why can’t you live in your own country? Are you legal immigrants? Are you going back?

Smoky did his own presentations. He addressed groups like the Elks and Sertoma clubs, since elderly residents were the most critical of the new immigrants. At first, he was frequently asked about cats and dogs “disappearing.” No, Smoky would say, Karen people aren’t eating them. They may have eaten wild cats and dogs in the refugee camps, but that was because there wasn’t enough food.

What about the fish tanks in their basements? The live chickens in their cupboards? Smoky assured them that he visited Karen people’s homes all the time. No basement fish, no cupboard chickens. If he heard a new rumor spreading, he’d ask Karen people about it. Then he’d address the rumor at the next meeting before he was even asked about it.

On a typical day, Soe, now 31, volunteers for the Karen Association from 8 a.m. to 11 a.m., works a full shift at a center for people with disabilities from 11 a.m. to 9 p.m., and does another half-shift at a clinic, before returning home well after midnight. Her eldest daughter, Mu Mu, who was born in the refugee camp when Soe was 15, is distressed that her mom’s hair is already going gray.

If a Karen person needs money, she goes door to door soliciting donations from members of the community until she has enough. But Soe’s ambitions extend beyond South Dakota. Her eventual goal is to split time between Huron and Thailand so she can help people who remain behind in the camps. She’s already taken Mu Mu, now a rising high school senior, back to visit.

Schools are often where the veneer of tolerance is torn off. As decades of opposition to busing have made clear, many white parents who say they’re open to diversity revolt as soon as they think integration is hurting their kids. Huron started down a similar path.

Laura Willemssen, Huron’s middle school principal, remembers when Tiger Paw and her siblings started school. Karen kids who couldn’t read were arriving in Huron fresh out of refugee camps. But the middle school was committed to keeping ESL students in the same classrooms with native speakers. Local parents weren’t pleased. There were four elementary schools in town, and they quickly self-segregated: As immigrant kids began to populate the schools on one side of town, white parents petitioned to move their children to schools on the other side of town, or out of the district entirely.

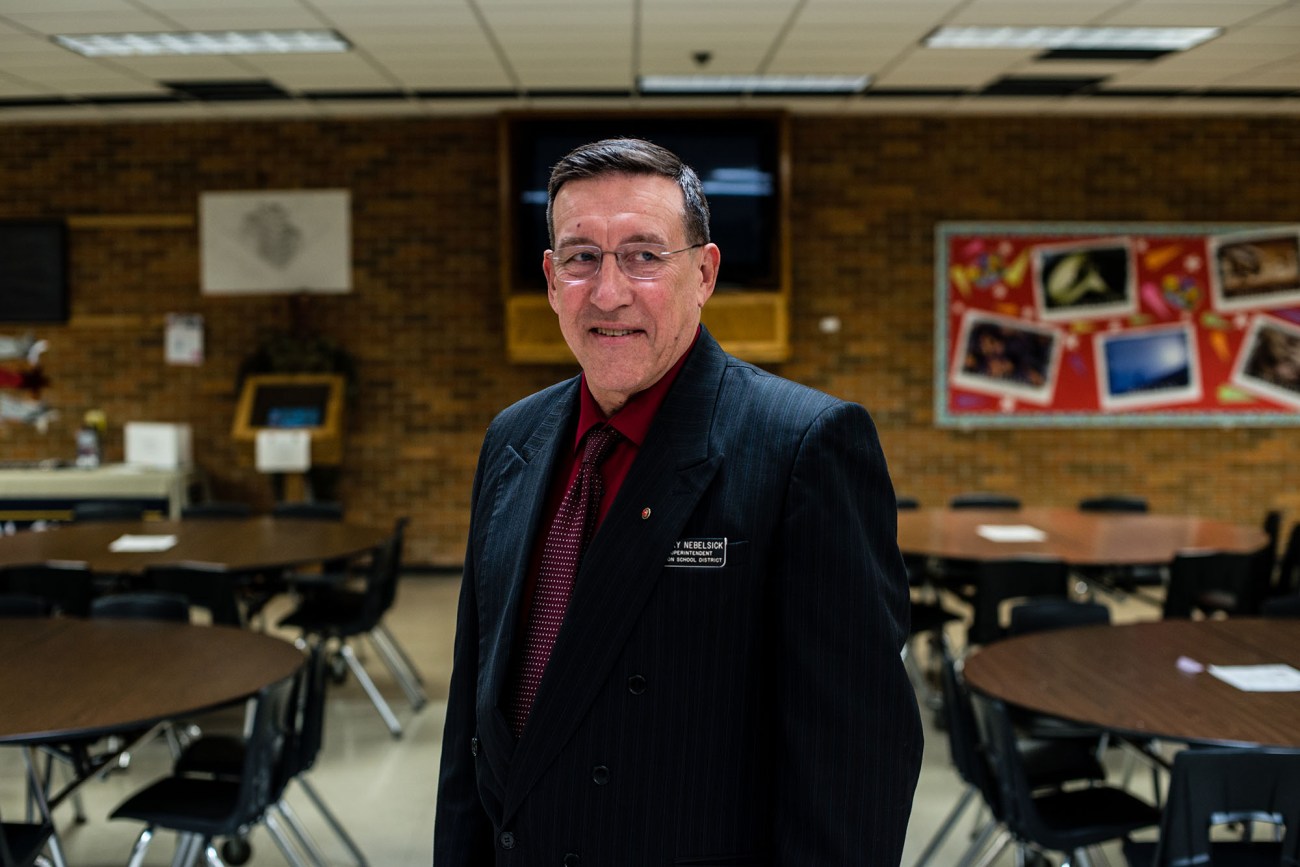

Superintendent Terry Nebelsick decided that Huron wasn’t going to be a place with “poor sections and rich sections.” Nebelsick says he was guided by “agape” love, a Greek term for the universal and unconditional devotion modeled by Jesus. In 2011, he and his staff arrived at a radical solution: They would replace the four elementary schools with three new schools. One would serve all of Huron’s kindergartners and first graders, another would cover second and third grades, and the last would be fourth and fifth. Instead of starting out segregated, kids in Huron would grow up in the same schools.

The plan faced obstacles, starting with the $22 million price tag. Its supporters promoted a ballot measure to secure a bond issue. It would require a two-thirds majority to pass. Huron residents were being asked to tax themselves in part to pay for school integration. Nebelsick and the measure’s backers talked to anyone who had questions and made a point of showing respect to those who disagreed. A citizens’ committee promoting the measure adopted an unlikely tag line in a county that then-President Obama lost by nearly 20 percentage points: “Yes we can.” The measure wound up getting 72 percent of the vote.

Thanks to the new immigrants, the number of babies born each year in Beadle County nearly doubled between 2005 and 2015. To accommodate the growing student body, Huron schools have added about 115 employees. The elementary school band and orchestra have grown from about 25 to more than 100, while the soccer team, whose players are predominantly Latino and Karen, nearly won a state championship. “The legacy of Huron is that if South Dakota is going to prosper—if its cities are going to be here for the next century—we’re not gonna look like we did 100 years ago,” Nebelsick said. “We’re gonna look like the world.”

As Huron became known for its immigrant population, opposing crowds at high school games would yell, “You’re from Huron.” It was meant as an insult, but the town’s kids came up with a chant of their own: “We are Huron!” “I think people come to Huron and say, ‘Look at the diversity,’” Willemssen said. “I don’t see the diversity as much anymore. I just see our kids.”

Two of her students took me on a tour of the middle school. We stopped in on a girls’ choir class. After learning that I was there to write about immigration, the teacher asked her students born outside Huron to share where they were from. The first responses—Illinois, Florida, New Jersey—weren’t what she was looking for. “Okay, that’s very cool,” she said. “Internationally, where do we come from?” Thailand. Cambodia. Malaysia. Vietnam. “We’re quite a melting pot,” she said. Then the girls launched into a tune. “Now let us all sing together,” they sang, “of peace, peace, peace on earth.”

No place, of course, is a blissful chorus. Just before I got to Huron, two Karen residents, ages 17 and 21, were arrested for allegedly shooting at (and missing) a police officer. A white Huron man responded to the news on Facebook by writing about immigrants, “GET THEM OUTTA OUR STATE AND COUNTRY.” But on a platform not known for moderation and restraint, the vast majority of commenters made no mention of the suspects’ ethnicity. Then-Mayor Aylward said none of the people who called him about the shooting brought up immigration.

I’d come to Huron in January to observe its 10th annual celebration of the Karen New Year. Several hundred people, mostly Karen, attended a ceremony that felt like a cross between a pageant and a civics lesson, with troupes of boys and girls performing Karen dances and songs interspersed with upbeat speeches from Soe and Aylward.

Smoky, who, like the mayor, was wearing a Karen tunic, struck a somber tone that irked some Karen people in the audience. He said God had called on him to discuss two emerging problems in the Karen community: drugs and suicide. He made clear that the issues weren’t unique to Karen people, but he worried that parents weren’t spotting the signs of drug dealing and weren’t taking advantage of mental health services. A Karen worker at Dakota Provisions, who requested anonymity, later told me that he felt it painted his community with an overly broad brush. The same things don’t get said when a white person does something wrong, he explained.

A banquet of Karen samosas and noodles restored the mood. The food was prepared with the white attendees’ spice-averse palates in mind, but there were also McDonald’s burgers stacked on the tables just in case. Smoky had introduced me to the crowd during his speech, and an older white woman stopped by to chat. She intimated that she’d been opposed to the immigration at first but had eventually come around to it. She left before I had a chance to ask why.

In 2012, the Burmese government reached a cease-fire with Karen separatists, ending a 63-year civil war. The number of Karen refugees arriving in the United States has plummeted in the last decade, falling from more than 12,500 in 2008 to 1,658 last year. There is no longer a steady stream of Karen people for Smoky to bring in, and many of the original recruits have moved on to jobs at other local businesses.

At the turkey plant, I spoke with Oscar Luque, the man Smoky is grooming to replace him when Smoky retires in three years. Luque, a Panamanian who came to the United States to play college baseball, said he couldn’t blame young Americans for not wanting to work in meatpacking. It’s repetitive and gory work. One job involves removing turkeys’ testicles, which are then fried and sold at baseball games as “Fowl Balls.” One Dakota Provisions job announcement began: “Kill. 1st Shift Only. Will be operating gas chamber…Will hang turkeys on line and keep production line going.”

Today, there are people from across the world following in the Karen’s path. In 2000, just one person moved to Beadle County from abroad or from Puerto Rico. In 2018, 499 did. With fewer Karen people to draw from, Smoky has turned his attention to places like Vietnam and Cambodia, where he recently went on a recruiting trip. His goal is to bring over families using a visa that provides green cards for up to 10,000 “unskilled” workers annually. His approach is unusual in an industry that has often relied on unauthorized workers from Mexico and Central America.

Although local leaders don’t mention it as much, there is a large Latino population in Huron, too. Twenty-eight percent of kids in Huron schools are Latino, while 21 percent are Asian. Latinos are an essential part of the local economy but a less visibly organized presence than the Karen. As refugees, Karen people quickly got green cards. Latinos in Huron often have no choice but to remain undocumented. Attention is not always helpful, and the Karen Association lacks a Latino counterpart.

At the high school, a young woman I’ll call Florencia told me in Spanish that she’d come to the United States in 2016 from a 500-person Guatemalan village where many lacked electricity and running water. After crossing the border alone, she joined a cousin in Huron and was now, at 21, in her last semester of high school. She’d gained a potential path to citizenship by marrying a Puerto Rican man, and they had a 9-month-old daughter.

Many others who cross the border do not have that option. They can work without authorization, but the open life led by Karen refugees is out of reach. Despite those differences, Florencia and other Central Americans I spoke with said they did not feel discriminated against, even though they were isolated by a language barrier that is fading as a new generation of Latino and Karen kids go through Huron’s schools.

I paid a visit to the high school journalism class to lead a discussion about past press coverage of Huron. I played a 2014 clip from a BBC report on refugees in the town, in which a man complained about the Karen arrivals. “I have ’em on both sides of me,” he said, pointing to his neighbors’ houses. “I’ve actually seen ’em slay a hog in the backyard. This is a retirement community. It’s very befuddling to see what’s happened.” Hei Say, an easygoing junior who hopes to become an elementary school teacher, was the only Karen student in the class. The man, she said, was her next-door neighbor.

As the class wrapped up, a senior named Bethany brought up a quote from a 2005 Argus Leader article that stated that Huron had a choice: It could accept immigrants or fade away. “I think that was the generation before us,” she said. “That was their choice. It wasn’t our choice. And they chose to accept and move forward and not to decline.”

She continued, “Now it’s our generation’s choice to choose to integrate, to combine what we have and combine forces and then keep growing. We don’t want to flatline at the acceptance.”

During the pandemic, there have been signs of what that might look like in practice. When COVID-19 came to Huron, rumors started spreading that immigrants had brought it to town. Aylward put out a statement making clear that wasn’t the case: All of the 13 cases recorded by late March were among white people. Eight more people soon got infected, but then the virus appeared to recede, and there were no new cases for more than 40 days.

In May, COVID-19 returned to Huron. By later that month, the town was battling 122 active infections, the large majority of which were tied to Dakota Provisions and a Jack Link’s beef jerky plant south of town. Blanca Ramirez Gonzalez, a 23-year-old Jack Link’s worker and mother of three who came to the United States from Mexico as a child, died at the Huron Regional Medical Center after testing positive. A GoFundMe page started by her aunt to help support Ramirez’s children, who range in age from 1 to 4, has raised about half of its $30,000 goal.

Smoky told me in early June that Dakota Provisions was taking people’s temperatures at the start of each shift, requiring masks, and placing partitions between workers on the line and in the cafeteria. He credited those measures with preventing a massive outbreak. (The Smithfield Foods plant in Sioux Falls is now connected to roughly 1,100 infections.) But the reality of the industry makes it hard to stop the spread. The Karen worker at the plant who requested anonymity said he thought the plant was doing a relatively good job when it came to protecting people from the virus. Still, he said, meatpacking means working elbow to elbow. More than 80 of the plant’s roughly 1,200 workers had tested positive by late last month.

As more workers fell ill or were exposed at home to relatives with the virus, Dakota Provisions found itself short on staff. Tensions rose as the company scheduled those who remained healthy for longer hours and came to a head last month when the plant stayed open for a Saturday shift. Roughly 100 workers, many of them Karen, decided not to show up as a form of protest.

Smoky responded with an internal memo to staff. “Getting together and purposely hurting Dakota Provisions today will hurt the company financially forever,” he wrote. “I do everything I can [to] support the Karen community every way I can.” He added, “When you do something like this, I struggle convincing the owners they should help you. Dakota Provisions has paid thousands of dollars building homes for you, educating you, paying for your celebrations, soccer tournaments, and recently paying you when you are too sick to attend work. You have greatly disappointed me!”

It served as a reminder that the Karen community had been coaxed to Huron to fill an economic void. Their activism threatened to upend the terms of that arrangement. The Karen worker asked me to imagine what it was like for older Karen residents to start work at the plant. “You don’t speak English and you walk into this place,” he said. “They just ask you to work, work, work. Do this. That. Overwork you. You want to speak up, but you don’t want to lose your job.” The memo left him “frustrated” and “speechless,” particularly because Smoky had been there for his community “high or low.”

The memo provoked an immediate backlash after it was shared on Facebook and covered in the local press. Young Karen people came to their community’s defense. Rebekah Htoo, whose family had moved to Huron in 2008, told a South Dakota reporter that she’d known Smoky since she was a kid and appreciated what he’d done for Karen people. The problem was the suggestion that people like her parents, who still worked at the plant, owed him something. “We were fine before him and we will be fine after him,” she said. “We can be angry and critical, without undermining everything positive that he has done for us.”

Dakota Provisions CEO Ken Rutledge responded by telling workers in another memo, “Smoky has been told never to allow this situation to happen again. To those employees who were upset, I humbly and sincerely, apologize.” Smoky told me in late June that he’d apologized in person to all of the Karen workers and that things were mostly back to normal. New infections in the county had slowed down and the work was continuing. Employees were about to come in again that Saturday for a half-shift to kill turkeys that were born before the pandemic had begun.

The night after the journalism class, young Karen bands played covers of Creedence Clearwater Revival and Guns N’ Roses on the stage where the new year’s celebration had taken place. I spotted the older woman who had approached me after Smoky’s New Year speech.

She told me her name was Emma. She was 80, and away from the music, she explained that her views on immigration had been reshaped by two Karen girls who visited her church group about five years ago. Emma brought them over. One was Khu Kle Shee, an energetic junior. The other was Hei Say, whom I’d met in the journalism class.

I apologized to Say for putting her on the spot with the video of her neighbor. “We had a misunderstanding with our neighbors, but it’s all right,” she said. She noted that the man was wrong to call the police on them for slaughtering a hog. “We were just skinning him,” she said. “The police didn’t care.”

Neither of the girls had known their grandparents, and Emma had become an improbable stand-in. They called her Grandma Emma; she called them Cookie and Hershey. “She’s watched us grow up,” Say said. “She’s given us a lot of advice. Relationship advice. Religion advice.”

“How to be young ladies,” Emma said.

When they wanted to learn how to bake, Emma taught them. They made her Karen food, but she couldn’t handle the heat. They laughed as they described other cultural divides. White people let the apples on their trees go to waste. They went to all-you-can-eat buffets, then didn’t eat that much. Kids at the high school didn’t always get the blunt Karen sense of humor. “You’re kind of ugly today,” Karen students might tell each other. The differences could make it hard to be friends with the classmates they sometimes called “English.”

Say and Shee found themselves caught between their peers and their parents, who worked in meatpacking. Both girls knew they’d never be able to handle that kind of work. “If we were there just for an hour,” Shee said, “we’d collapse.” Her mom and dad came home with backaches, but the girls weren’t exactly sure what their parents did all day. Neither had ever set foot inside the plants. Shee said she hoped to go someday, but just as a visitor.