At the entrance of the University of Mississippi campus in Oxford, the statue of a white marble man sits among the magnolia and oak trees. The gift from the Daughters of the Confederacy, a soldier, his arm in salute, a rifle at his side, has presided over passersby entering the university since 1906. He is perched atop a matching white marble spire so that the tip of his hat reaches toward the treetops. A plaque at the base of the monument, revised in 2016 as part of a historical contextualization project, allows that the statue was one in a series of memorials that “were often used to promote an ideology known as the ‘Lost Cause,’ which claimed that the Confederacy had been established to defend states’ rights and that slavery was not the principal cause of the Civil War.”

Still, it stands.

But now, after more than a century, the anonymous soldier will finally be ousted from his premier spot—a move that’s the direct result of a sustained campaign led by University of Mississippi students. “We still have a long way to go, but it’s still a victory, and I think we are allowed to celebrate it,” Arielle Hudson, a recent graduate and the university’s first Black female Rhodes scholar, tells me.

But it wasn’t easy to get here. More than a year ago, the Associated Student Body Senate for inclusion and cross-cultural engagement unanimously passed a resolution that stated, “Confederate ideology directly violates the tenets of the university creed that supports fairness, civility, and respect for the dignity of each person.” While plans were made with the university to move the statue, the Mississippi Institutions of Higher Learning stepped in, declaring that the marble soldier falls under its purview and putting the plans on indefinite pause.

But in this moment of broader racial reckoning spurred by the killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, the already thinning tolerance for hand-wringing over such symbols has largely evaporated. In mid-June, the IHL agreed to move the statue to a less-prestigious placement, keeping watch over the dead in a Confederate cemetery in an area with less foot traffic, behind an old coliseum that’s no longer in regular use.

Undoubtedly the ultra-conservative IHL relaxing its grip is an important step. Persuading the university five years ago to discontinue the use of the Mississippi state flag—which, until Gov. Tate Reeves signed a law to retire it this week, was the last state flag to feature the Confederate battle flag design—was a similarly important one. And so was the university’s pledge, just last month, to review its “admissions and judicial review policies and protocols” to deal with prospective students whose social media pages include racist posts.

Even so, each step away from the school’s “Old South” image ultimately seems marked by ambivalence. Soon after the announcement that the entrance’s Confederate statue would be moved, plans surfaced to renovate the cemetery to create a sort of “shrine” effect (though the university says the design is not final). And while it is unclear what exactly will change for its admissions and judicial review policies, the university’s stance has long been that it is unwilling to court costly First Amendment lawsuits, even as schools like the University of Alabama have expelled students over racist social media posts.

And, crucially, no matter what happens with these measures, there remains an implicit tribute to white supremacy on campus that has proven tougher to exorcise, one many people don’t even realize is there. The “Ole Miss” moniker has long informed the core of the institution’s identity and the surrounding community, not to mention its powerful brand. But this is not merely a convenient abbreviation of the long official name. It’s a phrase that’s long haunted Black students, faculty, and staff as a lingering nod to the days when it seemed unthinkable that a place like the university would ever accept them only because of their skin.

While statues all over the country come down, and the United States reckons with its racist past, it is time to confront the more insidious forms of white supremacy—especially those so easy to take for granted that it becomes harder and harder to recognize them for what they really are. They are not monuments or flags, but they are hidden in our language and our customs, their origins masked by time and intent.

When Zaire Love was accepted into the University of Mississippi’s documentary program to pursue her MFA, she was thrilled. In July 2018, she posted a photo to share the news that she would attend her dream school on full scholarship, no less; she looks uncertain but triumphant. Under a camo jacket draped perfectly off her shoulders, her white T-shirt is one she made herself: navy blue scripted letters sing “Ole Miss Mane.”

“I thought I was putting my Blackness and my Black flavor on it,” she says. She didn’t know just what it meant at the time, but she remembers her bitter disappointment the day she found out.

That summer, Love left her home in Memphis to mentor teenagers on campus through the William Winter Institute for Racial Reconciliation. She was eager to get involved in a new community, and the program seemed like the perfect way to jumpstart a new chapter in her life. While she was there, the origin story of the name “Ole Miss” came up.

Love learned that a student, Elma Meek, proposed the name in 1896 for a new yearbook that was being created by an interfraternity group. Her inspiration reportedly came “from the language of the Ante-bellum ‘Darkey,ʼ who knew the wife of his owner by no other title than ‘Ole Miss,ʼ” according to the student newspaper, then called The Mississippian. In an interview with that paper in the 1930s, Meek said she felt the name “connoted all the admiration and reverence accorded the womanhood of the Old South.” This intervention afforded Meek herself a vaunted spot in Oxford mythology; long after she had stopped attending classes at the university, Meek lived in a house near the campus that was built by a Confederate general. (For a while, William Faulkner and his wife lived with her there; it’s actually where he wrote much of As I Lay Dying and “A Rose for Emily.”) Today, the house is fiercely protected from any attempts at change, down to its air ducts, by the local Historic Preservation Commission. But more than Meek’s sentimental history, the name she proposed has stuck, so wildly outliving its origins that many, many people who pass through the Oxford campus or tailgate in the Grove or simply follow the sports teams with mild interest are unaware of the horrors hidden therein.

(The university did not respond to multiple interview requests from Mother Jones, but sent a statement from Chancellor Glenn Boyce: “Ole Miss is a term of affinity for many of our people that is intrinsic to the university’s identity and carries strong, positive national and international recognition. We understand the complex history of its origins…at the same time, it is a term whose meaning has changed over time, and we are committed to living by what it means today to our students and alumni who embrace it as an expression of caring and community.” The email also included a chapter from a book titled, The Other Mississippi: A State in Conflict with Itself; written by David Sansing, the University of Mississippi’s late historian, the selection emphasizes that the term “Ole Miss” was one of “respect and endearment” used by slaves, and twice says that Meek’s intention was not to “reminisce or regale” slavery, rather she only meant to “link her alma mater to those grand women of the antebellum South.”)

Upon learning this history, Love was determined not to use the casual nickname again. “I’m going to stand up and say this is not what I want to use,” she says. But, she admits, it’s not exactly easy to just remove yourself from something so wrapped up in campus culture—“It’s also the lay of the land. It’s a damned if you do, damned if you don’t–type situation.”

There are so many people—not all of them white—who do not know the university as anything other than “Ole Miss.” It’s everywhere around you in Oxford; on billboards that advertise the university as you drive into town, on signs and on campus, on T-shirts, ball caps, stickers, school supplies, tacked onto the end of every student’s and faculty member’s email address. There is no University of Mississippi; there is only “Ole Miss.”

For most of my life, I was among the oblivious. The historical context of “Ole Miss” was news to me when late last year a former high school classmate of mine posted a 2019 Chronicle of Higher Ed article on Facebook detailing origins of the university’s hoary nickname. I am a Southern white woman who has always spoken those words, “Ole Miss,” in the context of a dearly held rivalry between the university in Oxford and Mississippi State University, where most of my family has attended school for generations. It once vaguely connoted home to me, recalling Thanksgivings at my grandmother’s house in Tupelo, the television in the living room blaring the Egg Bowl, the annual football faceoff between the schools, as we cleaned up the kitchen and carefully put away the leftovers.

Jonathan Bachman/Getty

I’m not sure I’ve ever heard anyone refer to it as the University of Mississippi until recently, but the discovery that words that I once regarded as neutral, even charming, contain a bitter connotation has changed that. For weeks, I couldn’t stop thinking about this new context. I quizzed everyone I encountered about the once-beloved nickname; in bars, at work, on the phone with folks back home—no one knew. That racism often hides in language is not a new concept to me; I grew up as a white girl in the South. But that also means I hid from those realities behind my privilege and youth for an unforgivably long time. Even as a child, I often sensed some lingering evil when racism was dressed up as something innocuous—yet in the name “Ole Miss,” for nearly three decades, I heard only a folksy alternative to an unwieldy school name.

A few weeks after reading the article, I wandered the campus with my cousin, struck by the depth of the school’s commitment to the branding—wondering how I went so long without knowing, becoming fixated on how the name that literally looms over everyone’s heads affects life for students and staff of color. The student population is 76 percent white and only 13 percent Black; similarly, the faculty is 78 percent white and only 6 percent Black. “If you talk to students—and this is both students in general, Black, white, and otherwise, but especially with students of color—they will say that it weighs on their everyday experiences on this campus—the ‘it’ being the racial history of the campus,” says Brian Foster, an assistant professor in the sociology department, who is Black.

Interviews with students add further dimensions to Foster’s assessment. While Love is careful to point out that as a graduate student she is not on campus as often as undergraduates are, she notes, “Our ancestors already paid the price. We don’t need to add tax by continuing to have those symbols of oppression at the University of Mississippi.”

For her part, Yasmine Malone, a rising senior at the university, likes the nickname itself, stripped of its origins, but it bothers her that she feels like the school is less than clear about where it comes from. A classmate, Isabel Spafford, says she heard the claim on a campus tour that the name is taken from a train that supposedly ran through the state from Memphis.

Malone notes that despite efforts to move forward, there is also still an undeniable pattern of racism in behavior at the University of Mississippi—whether it’s the Black fraternity house that was burned to the ground in 1988 or the Confederate rally held on campus in February 2019 or the powerful old Southern families who donate to the university on the condition that the Confederate imagery remain intact and undisturbed. “I would like for us to adopt a mindset that we no longer want this to represent who we are,” Malone says. “But the fact of it is, that is exactly who we are. The political, economic, and social forces that guide decisions around Ole Miss are all very much still racist.”

She clarifies that she’s being more candid with me than she feels she can generally be in her life on campus.

While the University of Mississippi has grappled with its Confederate history for decades, wrestling with these demons never makes for a straightforward fight. And in the broader context of the state of Mississippi, where strains of white supremacy persist from the not-so-distant past, it has been even more fraught.

In 1848, the university was “very explicitly founded as an institution where slaveholder sons can attend rather than going to those fanatical colleges and universities in the north where they might imbibe anti-slavery ideology, and come back hostile to the institution,” says Anne Twitty, an associate history professor at the University of Mississippi. “The overwhelming majority of the University of Mississippi’s first students came from slaveholding families.”

As Twitty points out in a recent piece for the Atlantic, when the various monuments and memorials to the Confederacy began to appear on campus in the late 1800s and early 1900s, they were constructed not in grief for lives that had been lost, but rather in celebration for the power structure preserved through Jim Crow.

The university did not accept its first Black student, James Meredith, until 1962, and Meredith’s acceptance came only after a lengthy legal battle. Violent protests ensued; two died and some 300 more were injured.

“It’s a practical matter,” Foster says. “If Black folks have only been allowed to be here, either as students, as faculty, as administrators, for a fraction of the university’s history, it only follows that they will be underrepresented in those spaces to which they haven’t historically had access.”

He adds, “Why would we expect this to be a habitable place? Why would we expect this to be a welcoming and vibrant place?”

In 2006, a statue of Meredith was erected on campus. In 2014, three fraternity brothers flung a noose over its neck.

The university has made attempts to tackle some of the most glaring representations of this racism, but its official actions don’t always translate to the broader culture on campus. For the better part of the 20th century, for instance, the school’s mascot was Colonel Reb, a mustachioed caricature of a plantation owner who wears a haughty expression, leaning heavily on a cane. He is sometimes depicted against a backdrop of a Confederate flag. The university officially retired him in 2003—but the image is far from defunct. Independent groups attend sporting events with stuffed Colonel Rebs for children; men dress as the former mascot and pose with sorority girls and fraternity boys.

Mark Humphrey/AP

In 2009, former Chancellor Dan Jones asked the university’s band, known as the Pride of the South, to stop playing “From Dixie With Love,” which blended the Battle Hymn of the Republic with Dixie that builds toward a chant: “The South will rise again.” In 2016, they were asked to stop playing any variation on the unofficial anthem of the Confederate States of America. Like the mascot, both songs have disappeared officially, but that does not stop tailgaters from blaring the anthem from booming speakers in oversize pickups anyway.

Even though the school banned the Mississippi flag on campus because of the Confederate symbolism prominently displayed therein, there’s still the Our State Flag Foundation, a group of people pissed that the university no longer flies it. The Facebook group, which hovers around 25,000 members, is a forum where angry white people bemoan diversity and inclusion efforts on their best days and attack specific people of color in the university community on their worst. They have a booth in the Grove on game days.

The way the university has dealt with the name has been even more opaque. In 2014, a Sensitivity and Respect Committee, comprised of administrators and other faculty, and a handful of students, aimed to make the campus more diverse and inclusive, releasing a report that alludes to the moniker but avoids addressing its racist history directly. While the official recommendation is, the University of Mississippi should “consider the implications of calling itself ‘Ole Miss’ in various contexts,” most of that section of the report appears to brush the roots of the name aside: “Regardless of its origin, the vast majority of those associated with our university has a strong affection for ‘Ole Miss’ and do not associate its use with race in any way. And the vast majority of those who view us from a distance associate the term ‘Ole Miss’ with a strong, vibrant, modern university – and the Manning family, The Blind Side, The [sic] 2008 Presidential Debate, and great sports teams.”

In June 2017, another report, this one from the Chancellor’s Advisory Committee on History and Contextualization, was released. It held specific instructions for clarifying the history of the Confederate iconography on campus—everything from the names of buildings to the 12-foot-tall Tiffany stained-glass window depicting the University Greys, the students who fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War (all of whom were killed or wounded in combat). It was, in many ways, a massive victory for the Black students and faculty who had long been fighting for a more inclusive, reflective campus. “Ole Miss,” though, was not even mentioned in this report.

“Those efforts for change have always registered to me as symbolism, surface level, more than tangible, material, structural,” Foster says.

Part of this may be because if the University of Mississippi is a formal name, “Ole Miss” conveys a powerful emotion—and a lucrative brand. As Hudson put it to me, “We have not moved on from [Ole Miss] because of capitalism…they’re making money off of that.” Forbes estimates that the annual revenue—over an average of three years—brought in from the “Ole Miss” football program alone is $84 million, making it one of the top 25 most lucrative college teams in the country. In 2016, the school expanded Vaught-Hemingway Stadium to hold 64,038 football fans; it is now the largest stadium in Mississippi.

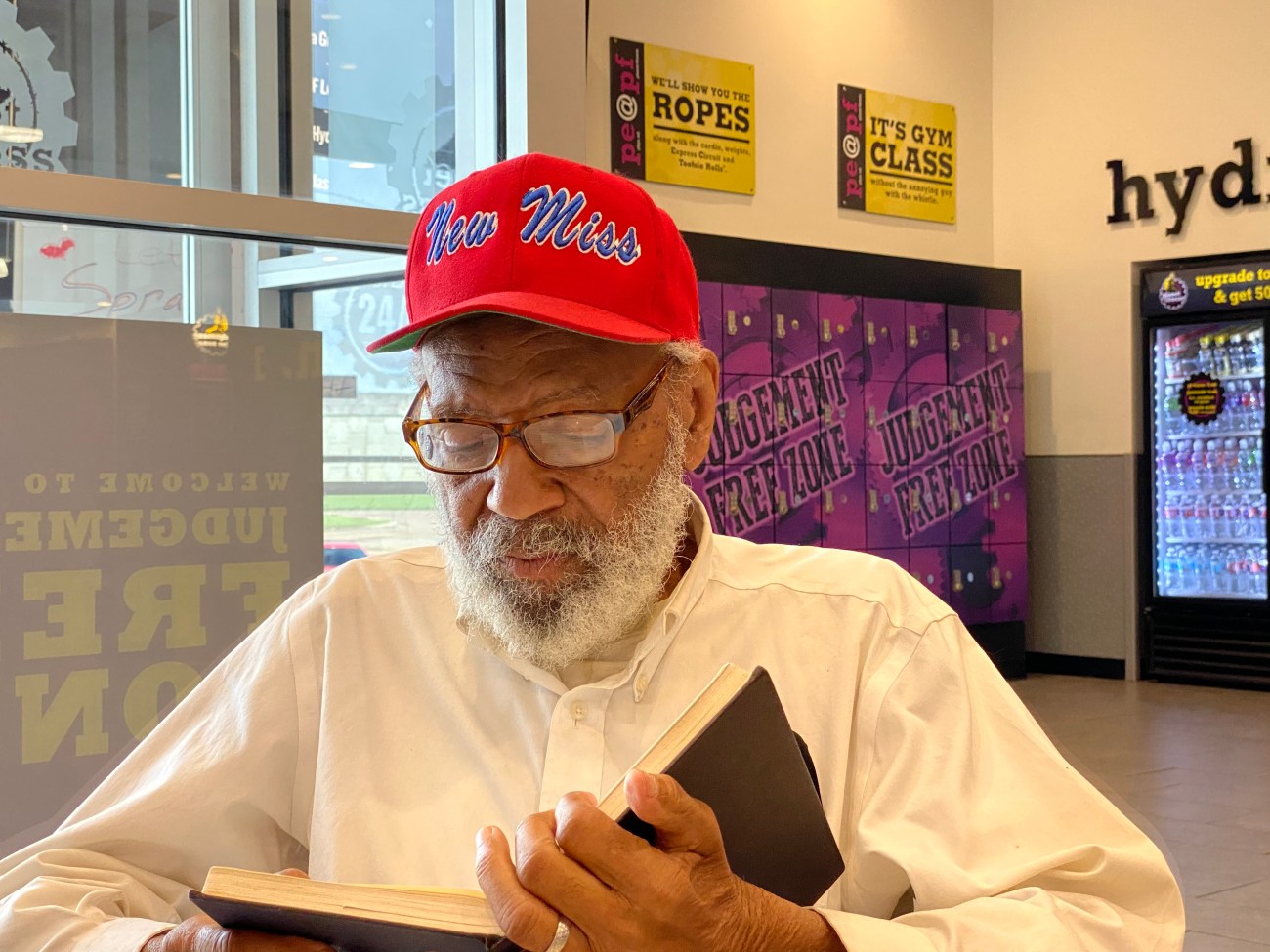

Still, grassroots efforts to change the name have come in small fits and starts over the years, though the overall conversation has lacked the urgency that has toppled other Confederate symbols. And when it has come up, it has typically inspired only lukewarm response. Torie Marion White, who serves as an assistant director at the Ole Miss Alumni Association, overseeing alumni relations for the School of Applied Science and the School of Engineering, as well as the Black Alumni Advisory Council and the Grove Society, tells Mother Jones that several of her fellow Black alums have taken to referring to the school as “New Miss,” she says, creating T-shirts and tumblers with their moniker featured in place of the old. Nevertheless, such swag is hard to come by; when I searched for anything like that online, I came up only with beauty pageant references.

Just this year, Zach Borenstein, a white graduate student, wrote an op-ed in the student newspaper, the Daily Mississippian, calling for the death of “Ole Miss.” “Language matters, but we often get used to saying things that normalize harm,” he wrote in early February. “Certain phrases diminish or denigrate groups of people, and if not addressed, these phrases become so commonplace that those using them do not even consider their origins and effects.” (At the end of May, Borenstein was arrested for defacing the Confederate statue at the campus entrance. He slashed his hand with a knife to cast bloody handprints upon the white marble, framing the words “spiritual genocide,” spray-painted in black.)

A week after Borenstein’s op-ed published, another appeared, this one by a white then-junior named Lauren Moses. It was headlined “Let’s keep saying ‘Ole Miss.’”: “My friends and I recently discussed the waning respect for tradition on our campus. From changing the school mascot to governing bodies voting to move the Confederate statue to contextualizing many buildings on campus, Ole Miss has lost its identity.” The core of her argument is that history fades, and that those symbols are not celebrated for their origins, but in spite of them.

Her point isn’t particularly novel; it is in fact all too familiar. It ripples through the campus and an extended community of (mostly white) fans and alumni in all sorts of forms. Alumnus Jon Rawl, co-founder of the Colonel Reb Foundation, lobbies the university to bring back the mascot from the early aughts. I asked him what he’d say to Black students and faculty who are disturbed by the Confederate imagery on campus, including the mascot. He replied simply, “Well, the Confederate stuff was there before they were.”

Over the past few weeks in particular, I’ve considered what it means to love the South, as I deeply do. What once was partially buried under decades of careful erasure is now stark and exposed. I cannot look away from racism, especially where it flourishes in my home.

Harm is difficult to quantify, which in turn makes it a tricky defense against the thing that harms. When people who have been actively disempowered are those being harmed, it makes those voices harder to hear, or maybe easier for those in power to ignore.

As I talked to more and more people in the campus community—most of them Black—I couldn’t help but feel the magnitude of all they are up against. Before Foster was a sociology professor, he came to study at the University of Mississippi as a student. He tells me it was the first time he feared for his safety based on his identity. Oxford was the first place he was ever called the n-word by a white person. It was the first place where two white boys pulled up next to him at a stoplight, rolled down the window, and asked, “Where you boys going tonight?” like they were entitled to know. While scrolling through the Our State Flag Foundation’s Facebook page, I came across a screenshot of Foster’s staff page, and my stomach churned, alongside a photo of two Black female graduates. They had drawn the ire of the group for their activism to remove the state flag from campus. There are 69 comments below.

Similarly, Marion White, who runs the Black Alumni Advisory Council, says she’s “been the only minority in a room my entire life,” and still, the day came when she was manhandled by a campus police officer because she was in the parking area for elite alumni on game day. When she told him she worked for the university, he wouldn’t believe her. (Marion White says the officer remains on the force.)

My conversations with students echo these experiences. Malone, the senior, tells me that while she’s found a vibrant Black community at the university, she has stepped back from activism and fighting back against the university’s Confederate symbols. It’s become too much for her emotionally; she has to focus on her studies, which is a tall order in itself when attending classes means passing former slave quarters and hearing her university referred to in antebellum language.

Love is still committed to getting her MFA, but concludes, “You really do have to have a lot of strength and a lot of energy to continuously put your Black or Brown body in these spaces and fight for those things, because it is not for the faint of heart.”

Most of the men and women I interviewed also mentioned a photo that went viral in July 2019 of three white fraternity brothers, wearing broad smiles and posing in front of the bullet-ridden sign memorializing Emmett Till, the Black 14-year-old who was tortured and lynched in 1955 after a white woman falsely accused him of whistling at her. Two of the boys in the photo held guns. The sign itself is so often vandalized, so frequently shot at, that it’s impossible to know if the bullet holes are from the guns clutched in the hands of the Kappa Alpha brothers. They were suspended from their fraternity, but ultimately allowed to remain enrolled as students.

“I just feel like if those boys were Black men who shot up a Confederate sign, there would probably be way more consequences, way more outrage, way more punishment for them,” Love tells me. “You understand that the underlining thing about it is this deeply entrenched white privilege and to me, being a woman of color, a Black woman, particularly…it just makes you feel powerless.”

This incident reveals a bright line for these individuals on campus, where all the changes made so far seem to stumble short of addressing a larger cultural problem. The university has put a significant amount of time and money into trying to leave the past behind, but it cannot truly overcome its legacy when it chooses to retain an identity that romanticizes a time when Black people were considered so subhuman that they could not address a white woman directly.

A name that is so intertwined with the identity of a place is tough to disentangle. Some of the students who make a conscious effort to use the full name of the university would slip up in our conversations; I have promised myself to make the same effort and sometimes my tongue still catches on it. To stay vigilant enough to thwart the connection between your eyes and your ears and your mouth and your mind requires a kind of prickly awareness that feels uncomfortable at first, but soon, it dissolves into normalcy.

It is difficult to imagine the University of Mississippi as anything but “Ole Miss.” It is also impossible to completely divorce the school from the values held in its Confederate past without going all-in on moving forward and making the change. Moving statues, contextualizing symbols, building committees, and scheduling programming toward a more inclusive and diverse campus are all good and important. But that work feels dwarfed by the name of the place, when the words on the lips of everyone in that community are an homage to the antebellum South. Language provides all sorts of nook and crannies for white supremacy to hide; can it be truly overthrown without addressing what’s really in a name?

Suzi Altman/Zuma

Names, though, even the ones so tied up in a community, in its identity, can change. Look around. This reckoning over what’s in a name, which has played out time and time again, and time again, is once again doing so in the names of schools and parks and military bases and even country music bands. With time, few will remember what they once were. Once, the University of Mississippi was simply that. It could be that again; it could also be reborn as something better.

It may not happen today or tomorrow. But it will. It must. Of course changing the name will not magically dissipate centuries of systemic racism and inequality, but it is a simple step forward. Until then I feel somewhat heartened thinking about the fight itself—which, Love says, “is important because it shows that we are here, it shows that we belong, and it does not validate our worth, but it does validate us being here.”

“It shows that hey, we’re here, we’re staying. We acknowledge that these things, these symbols, hurt.”

Correction: An earlier version of this article applied a term for the original Confederate States flag, in use 1861-1863, to a later version formerly displayed in the state flag of Mississippi.