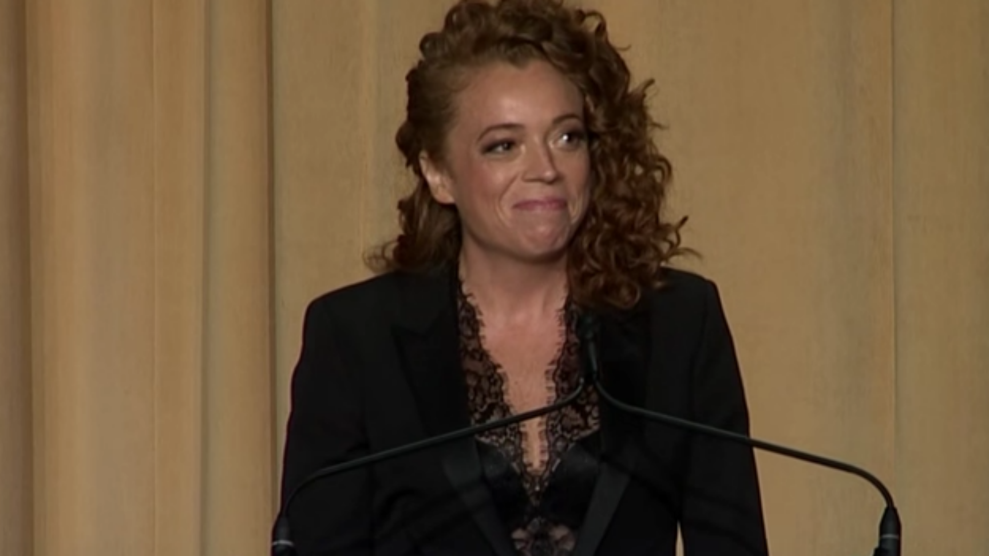

Mark Helenowski/Mother Jones

Actor, activist, author, and educator John Leguizamo loves that his comedy makes people feel angry. In his 2018 one-man Broadway show, Latin History for Morons (now available on Netflix), the 55-year-old star splices raunchy jokes with history about the genocide of Native American people, his experience being racially profiled, and a welter of statistics about the underrepresentation of Latinx people in American media. Born in Colombia and raised in Queens, New York, Leguizamo grew up seeing negative portrayals of Latinx people in Hollywood and in the pages of the New York Times. This feeling of being an outsider, of not belonging, was a power that he eventually came to value—and harness as fuel for his comedy and acting career.

In January, Leguizamo sat down with Mother Jones’s DC Bureau Chief David Corn onstage at the Comedy Cellar, the historic New York City stand-up venue, to talk about his work, his ego, his process, and his favorite subject: Latinx history.

Corn’s interview with Leguizamo is one of several notable guests featured over the next three episodes on the Mother Jones Podcast—a special summer series with a very “2020” origin story. Earlier this year, the coronavirus pandemic stalled work on a new podcast, co-produced by Mother Jones and the Comedy Cellar, but not before three fascinating guests joined Corn for in-depth interviews about art, politics, comedy, and the philosophies that infuse their work. These chats were too good to simply shelve; in the coming week’s you’ll also hear from music icon Debbie Harry, and talkshow host Samantha Bee.

Listen to the full interview with John Leguizamo on the Mother Jones Podcast:

A transcript of Corn’s interview with Leguizamo is below, edited for length and clarity.

David Corn: In October 2016 you were working to register Latinx voters. You said Trump was good for Latinos because he was bringing together a group of people, people from Mexico, Cuba, Puerto Rico, Colombia, Venezuela, in the Dominican Republic, who hadn’t always seen themselves as part of a larger unified community. Well, what happened?

John Leguizamo: He’s a horrible human being who does a lot of horrible things, but he’s so horribly blatant about it that he galvanizes us. We were asleep at the helm, bro. All of us—white liberals, moderate Republicans, independents, Latin activists, black activists. He got us woke. We are in a moral correction right now in our society, trying to make everything right because he does everything so wrong.

I was never as political as I am since he was elected. I went to Florida, stumped for Hillary. I went to Vegas, stumped for Hillary. I’ve never done that for anybody. I went to Florida and I flipped the seat that was red for 30 years in Hialeah, a Republican city. We flipped that blue. Beto and I tried to flip Texas because we believed we could flip it with Maria Teresa Kumar. Texas is 40 percent Latin, 12 percent black. It should be a blue state, but for gerrymandering, voter suppression, and all the horrible things. This is a democracy! How do you make it so difficult for people to vote? Maria Teresa Kumar, she and her lawyers came up with a way around that is called VoterPal. We have to be so clever now and so active. It’s not a spectator sport anymore, being an American, you have to throw your hat into the ring now.

In your book Pimps, Hos, Playa Hatas, and All the Rest of My Hollywood Friends: My Life, you noticed that you felt like a second class citizen in the United States. And then 14 years later in Latin History for Morons you say the same thing. And I was just wondering if there’s been any change, any progress, or do you look at it a different way?

Look at these facts: We Latinx people are the second oldest ethnic group in America after Native Americans, with the largest ethnic group in America after white people. Where are we? What are our percentages of success? Less than one percent of government officials. Less than three percent of the faces in front of the camera in Hollywood or behind the camera. Less than one percent of the stories in the New York Times, New York Magazine, New Yorker or any other rag that has the city’s name on its banner, when we’re equal to whites in population in New York City. We’re 40 percent of the population in Texas and less than seven percent of the government officials. That’s not okay. That’s not alright. That’s cultural apartheid. I’m living in a cultural apartheid. It’s demoralizing. It’s demeaning. It’s painful. And you have to fight this with yourself. You have to build yourself up every day before you leave your house. To be able to confront all this, these micro aggressions, upon you daily.

With all your success, do you still feel this?

Yeah, of course. It’s hard to get rid of. I see it happening. New York City has three of the best gold standard public schools in the country: Bronx science, Brooklyn Tech, and Stuyvesant. It’s supposed to be the schools that help the poorest children in New York City make it. Less than five percent of those children are Latin. Why is that? How is that? that should not be happening. That outrages me. How can I feel okay with all my success and fame, and this is happening to kids that look just like me? That’s not okay.

You’ve been very critical about Hollywood, where you make your make a lot of money, for not casting Latinx people in a positive role, but even more importantly, not having them in the decision making positions.

Well that’s where I find that the problem is. [Los Angeles] is 50 percent Latino, and less than three percent of the faces in front of the camera or behind the camera are Latinx. That’s cultural apartheid. It’s like we don’t exist. How is that possible? It’s not for lack of talent. It’s not for lack of trying. It’s that executives don’t see our stories. They don’t see us. They don’t understand us. I’ve been trying to sell scripts for the last 30 years of my life. It’s been impossible. The movie I just did, Critical Thinking, is a true story about five Latin and black kids in the ghetto-est ghetto Miami who became United States chess champions in 1989. It was impossible to get it done. I had raised the money myself. And it was a brilliant story. But dude, it’s hard without Latin execs.

Mark Helenowski

Now isn’t there a market imperative? The accelerated growth of the Latinx population in the United States, doesn’t that get them thinking, hey, we’ve got an audience out there?

We’re 25 percent of the US box office. We added $2.3 trillion to the US economy. If we Latin people had our own country, we’d be the eighth largest country in the world, the second largest state in America. They know that, but until you have a Latin executive who understands us, who sees us, until you have editors at the New York Times who live in our culture and appreciate our culture, where are you going to get the better stories about Latin people? Who knows that Prince Royce sold out Yankee Stadium twice, two nights in a row. No white or Black artists or any other artists in America has done that. Why isn’t that in the New York Times? Why isn’t it in the New York Times that we Latinx people have the 10 top hits internationally in the world in music today? Where’s that a big feature in the New York Times or New York magazine? That’s crazy. I got more facts. I got more shit to say. I ain’t done yet. An hour may not be enough.

I did watch Latin History for Morons, and you talk a lot about the conquest of the Americas by the Spaniards and what you call the “Great Extermination.” You can give us statistics because they are absolutely overwhelming. We all know how many people perished in the Holocaust. We

don’t really talk about the numbers of Native Americans, let alone indigenous people throughout North America and South America. And I wonder why you think the terminology, calling this the Great Extermination, why it hasn’t been more widely used and accepted?

Because once you start acknowledging the oppression, the exploitation of Latinx people and Native Americans, once you start accepting that this country was stolen, it’s hard for people to live with that. It’s hard for people to accept that because then you feel like you have to do something about it—reparations and whatnot. And and when you knew that there were 100 million Native American people in North, Central, and South America, and then 95 percent of them vanished through disease brought in by the Europeans, extermination, mutilation…. I mean, all kinds of horrors. Columbus was a horrible, horrible human being. He raped nine year old Taíno girls and bragged about them in his journals.

Tell us who the Taínos were. I have to say I learned a lot from Latin History for Morons. There was some elemental facts about the history of our culture that I forgot. And to think about these stunning gaps in our collective ignorance.

I love that. That’s the name of my next show, “Collective Ignorance.”

So can you talk about the Taínos?

There were 3 million Caribbean Native Americans under the under the Arawaks, and Taínos was was a branch of them. They were in Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Hispaniola (Dominican Republic and Haiti). And they were completely exterminated. Except a lot of my friends who did their DNA from Puerto Rico, Cuba, and Dominican Republic found that they have like 5/10/20 percent Native American, so it’s got to be Taíno. So that’s the beauty of knowing that their DNA is that we know they still they’re still alive, somehow, you know.

Yeah but basically it was a whole people completely wiped out.

Yeah it’s called the Caribbean Holocaust.

Now I have to say Latin History for Morons is pretty funny.

I know, it’s hard to believe that it’s a funny show!

We’re talking about genocide, extermination here, but I don’t want to give anyone the wrong impression.

But dude, that’s what my comedy has always been about. And that’s what my fight with American comedy was. It was like it never really captured life the way I grew up. I grew up laughing and in pain and oppressed and racially profiled but I still laughed, I still enjoy my life, and that’s what I tried to bring to American comedy through all my work.

What do you think resonates most with the audience? I mean, I’m sure every audience is different. But you’ve been doing this for over a year now longer. Can you tell from the stage what has truly connected?

There are moments of like raw honesty, of expressing the angst of what it’s like being Latinx in America still. I feel like I have to defend myself all the time. Sometimes you feel like everything is against you. And then the audience gets so quiet. I can hear sometimes people sniffling and quietly trying not to cry. I hear that in those incredible moments of silence. We sit there as if we were in church, and we meditate on that, and then I start doing some other crazy things. I wanted to show people that our history and knowledge of it can be weaponized, that it’s a call to action, that we need to spread this information. We got to get it into American history textbooks. We got to get it out there. There has to be that Ken Burns documentary on it. There has to be that Spielberg inclusion of our contributions to World War One and World War Two, because they’re massive.

We fought in every single war America’s ever had. I’m talking about the American Revolutionary War, where 10,000 unknown Latino patriots fought. Cuban women in Virginia sold their jewelry to feed the Patriots. [Bernardo de] Gálvez gave $70,000 worth of weapons to George Washington. He was General in Louisiana. He had a misfit army, like the Mets of armies. His blockade, with 3000 Puerto Ricans, Cubans, Mexican, Native Americans, and freed slaves, blockaded the British from the south. So they couldn’t surround the Patriots from the south and ambush them. Cuba gave over $200,000 worth of contribution donations to the American patriots.

Now we know about Lafayette, but where’s the Mel Gibson movie about this?

Right. I know it’ll be up to me and and Latinx executives that we get into power.

There’s a moment in Latin History for Morons where you say something like, if we were placed back in the history books, can you imagine how America would see us? How we we would see ourselves? You keep coming back to the way your culture internalizes the way it’s portrayed in the mainstream culture, right?

Or the lack of seeing yourself. Equally the negative images that Hollywood puts out about us, or New York Times just reporting the negative without equally putting positive. If you don’t see yourself positively or see yourself at all, the unspoken message is you’re not worth it. You’re not worthy. You’re not going to make it. And that’s what gets imprinted on the kids.

You can’t be what you can’t see.

Yeah, how can you project yourself into the future without seeing yourself in someone else in the past? Who looked like you, spoke like you, and had success? How do you, as a young person, build your self esteem? How do you build your self worth? I mean, your parents can try, but if society is saying the opposite, it’s a it’s a tough internal battle for Latinx kids and youth.

How did you do it?

I had a lot of mentors. I had a ton of therapy. I’m still in therapy. I’m still working on it. You know, it was rough. It was hard, man. I was a very troubled youth for all those reasons. High school forced me to go to therapy, thank God. And and that saved me. I started looking at myself in my life in America and I always felt like an outsider. And now I started to value my outsiderness, my sort of lack of placement in this society. It gave me some kind of power.

I really enjoy comedy. I always have. And I wonder what it is that makes something funny. And there are people like you who’ve made a career on being able to make others laugh or think something is funny. And I wonder to what degree do you think about how that process works: why do we find things funny? How can you as performer do something, say something that makes us laugh, and how often do you think something’s going to be funny that actually isn’t?

I still think shit that I say is funny, even though people don’t laugh. I still think it’s funny. It’s funny to me, that’s good enough for me. Laughter is just life’s greatest mechanism to keep us going, it’s the best thing ever. I’ve always had to be funny because to keep bullies from beating me up, from my dad beating me up. Funny was a thing that helped me through life. I still love it, it still keeps me going. Comedy is a science in a lot of ways.

When did you know you were funny?

I guess when I was like 13 and 14 because I would make people laugh and that’s how we would hang. All of us would be trying to crack each other up, all day, all night. I always tried to hang out with the people who love to groove like that, to vibe like that. We would just make each other laugh.

In the book, you basically call yourself an asshole a lot. You say actors are not human beings. Work is everything. We’re not really fit to cohabitate with other people. And I was wondering how true is that? Is that a shtick? Is there something about performers that make them more difficult?

Yeah, I mean, have you ever hung out with actors? It’s hard. They’re beautiful. But, especially the successful ones, there’s a level of narcissism that sometimes it’s hard to get through. You don’t make it to this level without a healthy dose of narcissism. And sometimes that’s a lot to put up with. My poor wife and my kids have to deal with it. I do like to talk about myself a lot. I do like to do voices and I like to, you know, sometimes steal all the attention. It’s just a natural thing that you’ve been sort of groomed for, but sometimes it’s too much.

You said not too long ago that American movies are so shallow. Do you think that’s still the case or do you think the rise of all these streaming networks, which produce so much content now, movies and unlimited series which are basically long movies…

Well it’s flip-flopped, right? Back in in the ’70s, which was the golden age of American cinema, and those were some great masterpieces of writing, of auteurship. Easy Rider, Harold and Maude, M*A*S*H, Annie Hall, Godfathers, Mean Street, Taxi Driver, Raging Bull, Apocalypse Now, Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, The Last Detail, Five Easy Pieces. It was masterpieces after masterpieces. So many great, great films. And then, not so great. Then American cinema became very much about the blockbuster, about getting butts in seats. It was no longer about the artists’ storytelling. And it’s getting worse and worse. I don’t really go to the movies anymore. Independent film is suffering. But, now TV is the place you go. Streamers and television are where the greatest writing, the the greatest acting, the greatest storytelling is happening now.