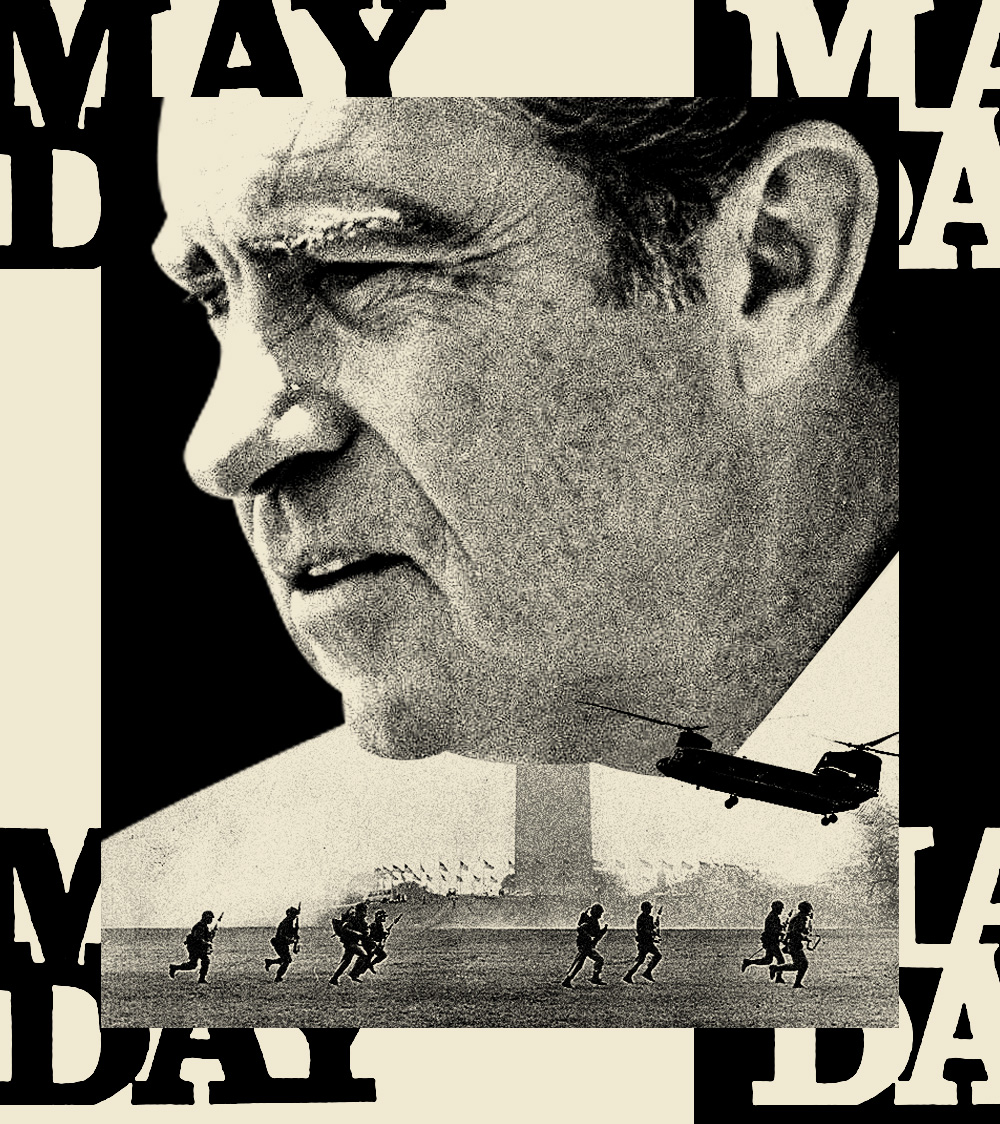

This article is adapted from Mayday 1971: A White House at War, a Revolt in the Streets, and the Untold History of America’s Biggest Mass Arrest (published Tuesday by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).

On the first Monday of May 1971, the police chief of Washington, DC, was in his cruiser well before dawn. In the darkness, Jerry Vernon Wilson picked up his police radio and broadcast to all hands the message he’d received on Saturday directly from the lips of Richard M. Nixon. “The desire of the president,” Wilson told them, “is that this city be open for business this week.”

For weeks, demonstrators had been flowing into Washington for marches, rallies, and sit-down protests, demanding an end to America’s war in Vietnam. The nonstop action had exhausted the police force and eroded the patience and confidence of the White House. Now the authorities worried about the finale of those protests, an action that would be the most audacious since the antiwar movement began six years earlier.

When the workweek got underway on May 3, the protesters, who called themselves the Mayday Tribe, planned to stream through the city, using their bodies and their cars to block bridges, traffic circles, and the approaches to government office buildings. Deprive Washington of its workers, and the federal city would stall. Mayday’s leaders hoped this unprecedented show of public disaffection would raise the “spectre of social chaos,” knocking Nixon off course and forcing him to bring all the troops home from Southeast Asia. For months, posters with the Mayday motto had been pasted on walls and bulletin boards at hundreds of universities, coffeehouses, and bookstores across the country: “If the government won’t stop the war, we’ll stop the government.”

Monday loomed as the largest act of mass civil disobedience the nation had ever seen, a coda to the most extraordinary season of dissent in Washington’s history. The chief knew he would be under scrutiny like never before, from the demonstrators, the press, city officials—and of course Nixon’s men. They were breathing down his neck. Richard Kleindienst, the deputy attorney general, arranged for one of his trusted aides to stick close to Wilson for the next three days. This would keep Kleindienst informed and, just as important, make the administration’s wishes known to the police chief in real time.

Still, Wilson permitted himself a bit of overconfidence. The day before, the chief had led his riot squad in an early morning raid on the Mayday encampment by the Potomac River. More than 40,000 people, most of them young, had arrived at West Potomac Park from all over the country, far more than Nixon’s men had expected. An all-day, all-night rock concert was a lot of the draw, but a good portion of the crowd had arrived to get ready for Monday’s blockade. It hadn’t been Wilson’s idea to secretly revoke their camping permit and force them to scatter; in fact he had initially resisted it. But now that it was done, he and his command believed the vast majority wouldn’t be back. The youngsters looked to be undisciplined, and there was no reason to think they had the capacity to act decisively as a group. Surprises were unlikely, since the cops had informants inside the Mayday planning meetings.

John Shearer/Life Picture Collection/Getty

So the police relaxed a little, and the bulk of the department didn’t get going until after 5 in the morning. The wagons, prisoner buses, and patrol cars aimed to get into position by a quarter to six. That would be plenty early, they figured, a good 15 minutes before the Washington traffic got heavy.

But the police were about to reckon with the consequences of their Sunday action. While the Mayday Tribe had appeared meek, the early show of force by the authorities had actually toughened the determination of the exiled campers. As for the thousands of other demonstrators in town—the ones who, instead of sleeping by the river, had found lodging in homes, churches, and dorm rooms—they now had absorbed both the news of the park raid and the early reports of troops pouring into town. It erased any doubt that the government would go to extremes. Perhaps the police and the army would try to bottle them up on the campuses or seal off their targets before they even got started. As a result, many groups decided to hit the streets early, before five. Within an hour, it became obvious to Wilson.

This was going to be a tough day after all.

Police and government agents had been warning for months about the Mayday promise of “mobile tactics,” essentially a kind of hit-and-run civil disobedience by small clusters of protesters called “affinity groups.” Officials largely dismissed it as just another bit of overheated radical rhetoric. But it didn’t take long for everyone to discover its potential.

It never had been a big problem for police to manage a static act of civil disobedience, one in which demonstrators would simply sit or lie down where they weren’t supposed to, refuse to move, and wait to be arrested as a symbolic act. In DC, the white-helmeted riot police typically would contain them with a formation they called a close squad column, planting themselves on the street like a row of intimidating fence posts. Wagons would pull up to the edge of the crowd, and officers would remove people one by one in an orderly fashion. If crowds became unruly, the police would aim for dispersal rather than detention. Their columns would sweep in formation through the area, firing tear-gas bombs to panic the crowd into a stampede. Suspects could more easily be picked off after a chase.

Now there were a couple of new wrinkles. During the 1968 riots after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., hundreds had been swept up for violating a citywide curfew and were held for many hours without specific charges. A blue-ribbon commission was set up to suggest methods that would both protect civil liberties and smooth the courtroom process in the midst of disorder. As part of the revised rules of engagement, police had agreed that during future mass detentions, they would fill out official records on the spot. These field arrest forms, as they were called, were shorter than the paperwork used at the station houses, so they could be completed quickly. In addition, police would have to take a photograph of each suspect with the arresting officer. To that end, the department had purchased a slew of Polaroid Swingers, the first cheap instant cameras, which had created a new mass market for pictures that developed as you held them with your fingers. (“Meet the Swinger,” went the ad jingle, sung by a young Barry Manilow.) Wilson ordered officers assigned to patrol wagons to bring lots of extra film and flashbulbs for Mayday.

All this was supposed to discourage indiscriminate arrests, and to make certain there would be no doubt in court who had busted the suspect and why. The 1968 commission had written, “If we are to be concerned with the quality of the justice, as well as the efficiency of the system, it is obvious that the police must be forced to exercise maximum responsibility in completing the record of the offense.”

Mayday would stretch this system to the breaking point. These new rules would prove “grossly inadequate” to cope with mobile tactics, as one of Wilson’s lieutenants would write in an after-action report.

The police and military response to Mayday was crafted in the weeks before Mayday at a series of war councils convened by Nixon’s men around a conference table in Kleindienst’s office at the Justice Department. They had been taken aback by the size and depth of the Spring Offensive, which was the name that disparate antiwar organizations had given to the series of demonstrations they brought to DC in April and May, a rare moment of unity for their movement. About a thousand embittered military veterans of Vietnam had been first to arrive. They camped defiantly on the National Mall and hurled their combat medals and ribbons onto the steps of the Capitol. Next, on April 24, came an enormous march of more than 400,000 people, almost certainly bigger than any previous gathering in the nation’s capital. “The people that lead this are left-wing sons of bitches,” Nixon declared in private. “They’re not patriots. I’ll lay you money, in that group that’s down here, you won’t find 1 in 100 that ever served in Vietnam. Little bastards are draft dodgers, country-haters, or don’t-cares.”

He and his aides fretted that the veterans’ protest, in particular, was turning public opinion in the wrong direction. The vets may be “the rattiest-looking people in the world,” Chief of Staff H.R. Haldeman told Nixon, but “they’re getting a hell of a play, which is too damn bad, because it’s so totally out of proportion.” Haldeman complained that there were “about six paraplegics” in the crowd and the press was writing “nauseating stories” about them. “God, everything you read would make you think all those guys out there had no legs!” he said. Henry Kissinger, the national security adviser, said, “I’m sure a significant percentage are phonies [who] get five minutes on national television every night.”

Outwardly, Nixon pretended that the demonstrations had no effect on him or his policies. When a caucus of Republican senators suggested a special meeting with the president about the Mayday protest, Nixon refused. In addition, the issue “should not be raised” at the regular weekly policy meeting between the White House and the GOP lawmakers, the chief of staff noted: “If it is, P will not speak to the subject.” Nixon arranged to be out of town during Mayday, at his Western White House in San Clemente, California. But he would stay on an East Coast schedule and would demand hourly updates from the White House.

Brooding at Camp David during the weekend of the April 24 march, the president had been obsessed with developing “a counterattack.” He wanted his aides to get out the word that television had covered the vets “in a totally unfair way” and to “be sure we’re alert to handling the violent demonstrations when they come up.”

Although the White House men had taken to calling the Mayday Tribe “the violent group,” and Attorney General John Mitchell branded its members as “terrorists,” there was no evidence, beyond the whispers from some sketchy informants, of violent actions on the agenda. No one had been talking about putting anything on intersections and bridges other than themselves and the occasional stalled car. But the Spring Offensive had already cost the administration some political points. Nixon’s inner circle was determined to chalk up a victory in the next and final round.

Estate of Fred J. Maroon

To do so, Nixon was trying to thread a very small needle. For his purposes, Mayday needed to be just troublesome and violent enough to obliterate any favorable opinion the average American might hold about the April demonstrations. “The next group comes in, just does a little destruction, that’s about what we need now,” he had told his closest advisers. But at the same time, Mayday couldn’t be robust enough to cripple the government’s operations because that could make Nixon look weak and incompetent; worse, it might reenergize the protesters. So the president had to undermine the protesters and be ready to hammer them down.

Most important, Nixon had to keep both tactics from the public. Revealing his deep concern could embolden the movement. And if things went terribly wrong during the crackdown—Chicago ’68? Kent State ’70?—the White House needed to be able to plausibly deny its role.

Kissinger helped stir the president up. As far as the New Left was concerned, the war wasn’t even the real issue, Kissinger insisted to Nixon. “They want to break confidence in the government,” he said. “They don’t give a damn about Vietnam, because as soon as Vietnam is finished, I will guarantee the radicals will be all over us” for other things.

Let them try, Nixon replied. “They know that they never will influence me.”

Then Kissinger pressed perhaps too far, suggesting obliquely that Nixon hadn’t been tough enough on the radicals. “I am wondering, Mr. President…whether one isn’t on the wrong wicket, batting back the balls they throw? Whether one shouldn’t accuse them of turning the thing over to the Communists?” He had hit one of Nixon’s hot buttons, and the president was stung. He said, “I think I have been on the offensive as much as I can be.”

Then Nixon added, “Or should I do more? I can hit them harder.”

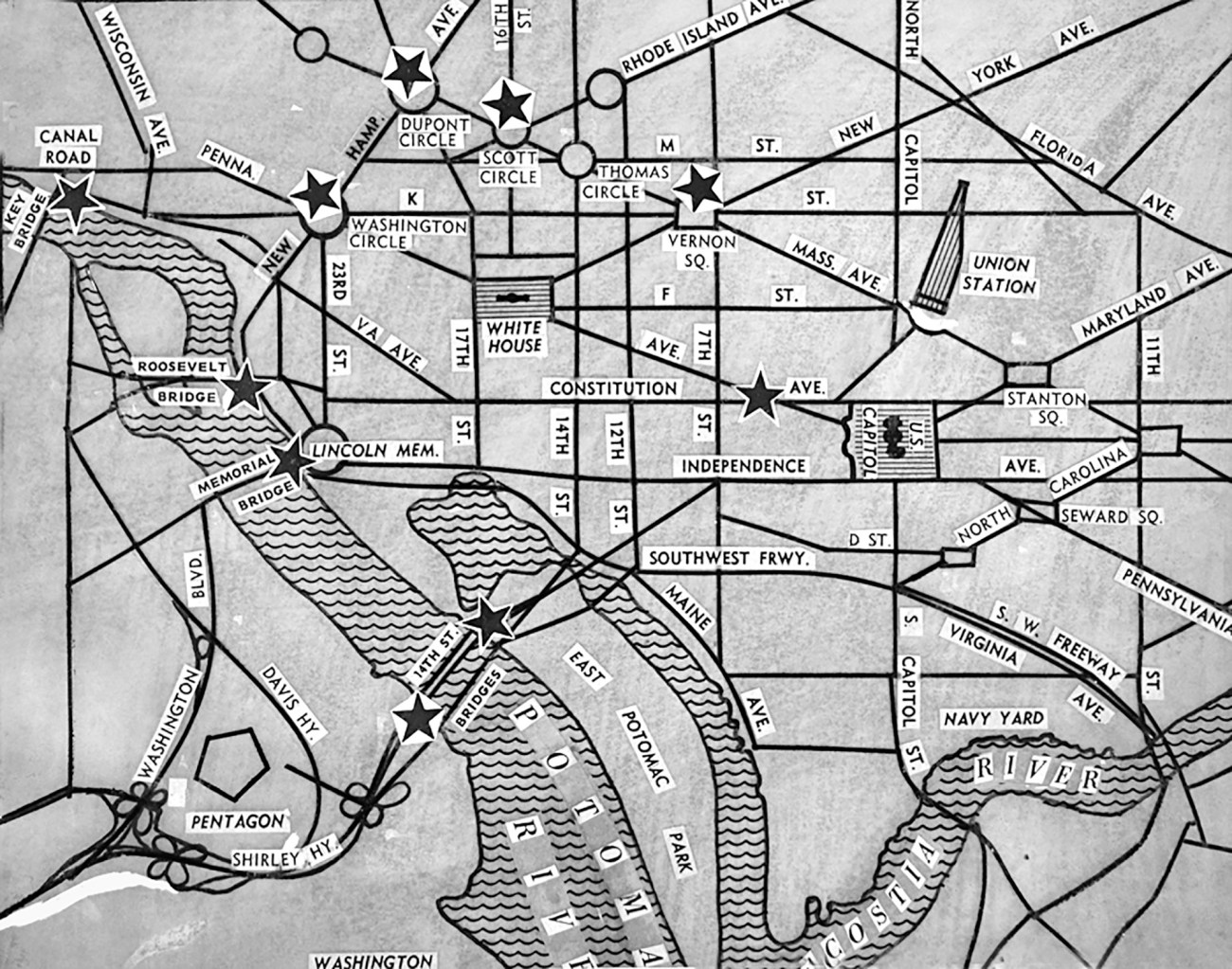

At first Monday’s action unfolded slowly. The Mayday Tribe had distributed thousands of copies of a 24-page “tactical manual,” with detailed maps and photographs of the targeted chokepoints, as well as tips for thwarting police. Site One was a busy intersection of several highways on the Virginia side of the Potomac, just over the Francis Scott Key Bridge. There, the river valley provided “excellent, low, flat, open areas” for a hit-and-run protest. Many of the drivers passing through every day, the manual noted, were bound for the Pentagon to help manage the reviled war.

Police had copies of the manual and thus advance warning about every objective. But demonstrators beat them to this target. A little before 5:30 a.m., dozens of people moved into the main feeder road, the George Washington Parkway, and erected barricades across the lanes, using whatever they could find, including small boulders they rolled down from the adjoining woods.

Across the Key Bridge sat Georgetown, the tony neighborhood that housed many of the city’s political and media elite, including plenty who had long championed the American presence in Indochina. Near Georgetown University, one group drove their car onto a freeway and managed to overturn it. Others sat down in the middle of Georgetown’s main commercial intersection. Still another cluster of protesters began stringing a cable across one of the busiest roads. Traffic was becoming hopelessly snarled. Cops with cruisers, motorcycles, or scooters scrambled to the scene. The demonstrators dashed into the adjacent woods or across the highway. The police fired tear gas and grabbed the few they could catch.

There seemed to be more Mayday people on the streets than Wilson expected. Still the chief thought the chaos seemed controllable. His conviction didn’t last long.

Courtesy DC Public Library, Washingtoniana Division

As the minutes ticked by, the police radio began crackling nonstop with reports from all over town. Several police cars broadcast emergency calls at the same time, talking over each other in rising anxiety. “Let one unit go at a time,” pleaded a desperate dispatcher. The transmissions became more garbled and distorted. “Lots of groups in the city,” reported one cruiser. “Large group at Seventh and D and Ninth and Mount Vernon—can’t tell where they are going,” said another.

Then faster and faster: “Large groups in Rock Creek stopping traffic on overpasses”…“All units — gas is being used on Prospect Street”…“Get your men out and lock them up”…“Expedite transport”…“Need a bus”…“Too big a crowd for the men there to handle”… “North Capitol Street, group heading south”…“Two cars overturned Connecticut and Calvert”…“Fourteenth and Jefferson, large crowd”…“Mount Vernon Park, large group about one thousand”… “a thousand at Nineteenth and New York”…“They have southbound Fourteenth Street Bridge blocked”…“Seventeenth and Q now being blocked.”

And finally, from all over town, with increasing urgency: “Send help”…“Need more help”…“Need people”…“Need more police”…“Need assistance right away!”…“Hurry up!”

By 6:30 a.m., “the entire police operation was in a condition-red status,” as one officer would later report, and it would not be long before both procedures and decorum broke down.

At the war councils the previous week, Chief Wilson usually had been the only city official among the dozen or so in attendance. The rest came from the White House, Justice, the Interior Department, and the military. The district didn’t yet have home rule, and its officials were appointed, so Wilson essentially answered to the president. Forty-three years old and 6-foot-4, Wilson had the calm self-assurance of a big man. He had been running the police department for less than two years but had spent his entire adult life as a DC cop. When he arrived in Washington as a 21-year-old fresh from small-town North Carolina, his drawl was so thick, it stood out even in a city still deeply rooted in the South. The year before, he’d become the first cop to receive the annual brotherhood award from the National Conference of Christians and Jews, which among other things had been impressed by the chief’s performance during three mass marches against the Vietnam War, all of which had gone off without widespread violence by the participants or the police.

Wilson had sought to calm the others, suggesting the threat from the Mayday Tribe was being exaggerated. He just didn’t believe these protesters were fundamentally different than the people who’d been keeping police busy for the past couple of weeks. True, there had been hundreds of arrests for sit-ins and the minor destruction of property. But the overwhelming majority of the demonstrations had been peaceful. And face it, the objective of Mayday was not to overthrow the government but to paralyze Washington for a day or so. Wilson could remember the huge blizzard that blew into the city a few years earlier, closing roads for days, crippling public transport, and triggering food shortages that led to some rationing. It was hard to imagine Mayday’s impact could be as bad, no matter how many protesters it pulled in.

AP

But for Kleindienst, the looming challenge presented a chance for a kind of vindication. The blustery and profane 47-year-old Arizona lawyer, who carried himself in an imposing stance that, as one friend put it, looked “like he was about ready to tee off,” had been one of the inventors of law and order as a national Republican campaign issue. He had warned for years that the New Left would grow increasingly dangerous if the government didn’t come down hard.

In addition to thousands of police and National Guard troops, Kleindienst wanted to call up 10,000 regular troops. He had already overridden the objections of military leaders, who were skeptical that the situation warranted exceptions from the Posse Comitatus and Insurrection acts, which effectively made it illegal to use the armed forces for domestic law enforcement in any but the most extreme circumstances. For example, Nixon’s predecessor, Lyndon B. Johnson, had followed the rules when he called in regular troops to help quell the uprising in DC following the 1968 King assassination. LBJ had issued a formal order that the crowds were to disperse and, when they didn’t, signed an executive order to bring in the soldiers. But if Nixon followed those rules everyone would know he was involved in Mayday planning, something the White House did not want. They wanted to maintain the fiction that all the decisions were being made by the police department.

Perhaps Wilson wasn’t pushing back as hard as he could have. But his job depended on the White House, which occasionally had snapped the leash to remind him. And there was one other thing Wilson couldn’t be expected to forget—the people in the room would have a big say in whether he might get a much bigger job, as director of the FBI. The talk that he could take over from the aging J. Edgar Hoover had been teed up again just the night before. The ABC-TV commentator Howard K. Smith said on national television that Wilson was “possibly the best policeman in the nation” and “would be a fine replacement” for the FBI chief.

By 7 a.m. that Monday, the skirmishes between police and the Mayday Tribe left a heavy fog of stinging gas floating over neighborhoods in Georgetown and along the National Mall, where government workers negotiated their way to the office with handkerchiefs over their faces. Many federal agencies made arrangements to avoid the blockade. Employees considered essential had been told to sleep overnight in their offices or book hotel rooms nearby. Some were ordered to their desks as early as 3 a.m.

Meantime, the police clashed with protesters on the Theodore Roosevelt Bridge and at Dupont Circle. A contingent of several hundred demonstrators from Illinois blocked traffic at Mount Vernon Square. At the sound of the sirens they ran off through streets and alleys. An elderly woman hid a group of them in her basement. She served them milk and cookies.

On scores of side roads, clusters of youngsters cried, “Motorists off the streets!” They linked arms to stop traffic or turned trashcans and construction equipment into barricades. “We are sorry for your inconvenience,” read a leaflet they handed to drivers. “While you are sitting in your car you could take a few minutes to think about things…You may not agree with the tactics being used—you may not agree with the points of view of the participants—but we ask you to consider with us the horror, the death, the destruction and devastation continuing daily in Indo-China…our actions now need to go beyond what we have done in the past.”

Many drivers were furious; many were resigned. Some flashed peace signs. Others gunned their engines and drove straight for the protesters. Among the latter was one of Nixon’s speechwriters, an arch-conservative named Patrick Buchanan, who generally put together the president’s daily news summary. He had just been over to the Watergate apartments to pick up his fiancée—one of Nixon’s receptionists—and they were headed to the White House in his Cadillac convertible when they ran into a Mayday blockade on E Street. Buchanan, who was 32, with a “beefy, beer-drinker’s face,” thought he might get around on the far right-hand side, where fewer protesters were standing. He hit the gas, and one kid jumped out of the way at the last second. Buchanan bragged about it when he got to work.

Some groups tied ropes across the road or pushed cars out of parking spaces into the middle of the pavement, letting air out of tires or removing distributor caps. The police scrambled to respond. They radioed for National Guard jeeps to push disabled vehicles out of the way. They sent squads of cops on scooters and motorcycles after protesters, like cowboys chasing a stampede. At one point, several police cruisers, their sirens screaming, gunned right over the curbs and onto the grassy fields around the Washington Monument, firing tear gas out the windows at sprinting demonstrators. But still they felt outnumbered and outflanked.

The tactical advantage underpinning the Mayday plan was now apparent: the asymmetrical warfare of a guerrilla force against a standing army. It was nearly impossible to defend against small decentralized bands who could shift on a dime, tie up police or troops at one spot, and then get to another place before the authorities could adjust, choosing spots that weren’t even on the original list in the Mayday tactical manual. Wilson realized that the police department’s procedures were being turned neatly against the cops, either on purpose or by luck. Dispersing crowds with tear gas so they could just move on wasn’t going to work, and the new field forms and Polaroid cameras were slowing arrests to a crawl.

From another police cruiser—apparently the one that held the representative from the Justice Department who was shadowing Wilson—came what may have been an order masquerading as a question: “Chief, do you think we should disregard field arrest forms and pictures this morning?”

One of Wilson’s underlings later summed up the dilemma: “We could either keep the streets of Washington open and the government functioning or we could carefully collect written documentation of arrest information for court. At this stage, we could not do both.”

A year before, Wilson had publicly upbraided his riot squad for failing to use field arrest forms in one big bust. And the chief had once promised the district’s chief judge that no prisoners would be accepted at a booking or holding facility without a field arrest form. He realized that if he broke this promise, it would be difficult, if not impossible, to defend the arrests in court. Nevertheless, minutes before 6:30, he made a fateful call: “Cruiser One to Command Center: We will disregard field arrest forms.”

He had taken the shackles off his cops.

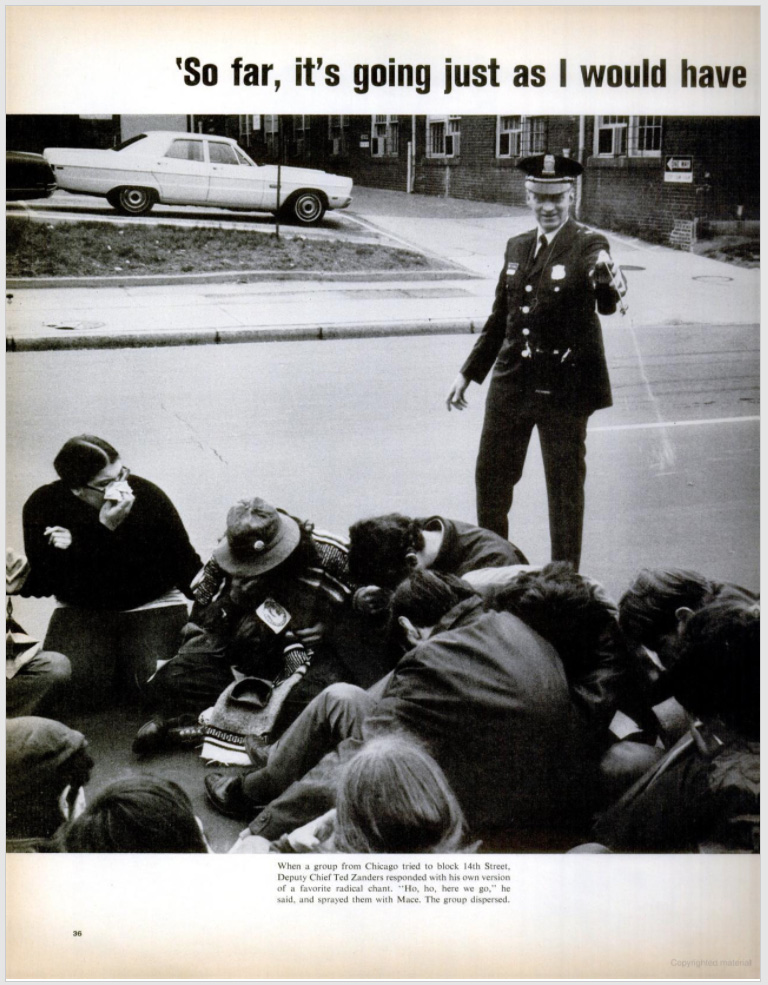

After weeks in a city under siege by dissenters, the cops no longer felt restrained. Their chief had freed them from the rules, and they vented their mounting frustration. Instead of arresting protesters one by one and recording which law each was breaking, the tactical squads began chasing down and grabbing big groups. Police were sweeping areas “clean of the Mayday mobs…We were hauling demonstrators off the streets in wholesale lots.”

Within minutes of Wilson’s order, for example, 100 people were busted in a sweep at Tenth and K Streets. A Life photographer captured the unbridled joy on the face of a deputy police chief, Theodore Zanders, as he sprayed Mace into the eyes and noses of one group. Even though the protesters weren’t breaking any laws at the moment, he felt justified because “the act of one is the act of all,” Zanders later explained.

Vans and buses that had been loading those arrested soon were “jammed to the gunwales.” The cops called in the backup transports; those vehicles filled up just as fast. Then the police started shipping their prisoners in the DC transit buses that had been used earlier to carry cops to the scene. They hastily procured more buses from the Navy and vans from automobile rental companies. On the buses the atmosphere was often festive. “We shall Overcome,” the protesters sang, and “Give Peace a Chance.” They banged loudly on the inside of the buses and shouted encouragement out the windows to young people still free on the streets. On some transports the cops warned everyone to be quiet or to risk being “bus gassed.”

The presence of Kleindienst’s regular troops magnified the image of a city under siege, feeding anxiety on all sides. Two hundred soldiers from the 91st Engineer Battalion at Fort Belvoir in Virginia guarded the bridges. A caravan of National Guard jeeps rolled down M Street in Georgetown. At Andrews Air Force Base, troops from the 82nd Airborne boarded six huge Chinook helicopters. They took off for the National Mall. A couple of smaller helicopters escorted the Chinooks and set down first, laying pink-and-white smoke flares for the landing zone near the Washington Monument. Then the Chinooks came in, their gigantic dual rotors slicing loudly through the air. Their exit ramps dropped, and out of each craft hustled 33 helmeted troops. Off they ran in single file toward the US Capitol, a startling image in a constitutional democracy.

Wally McNamee/Corbis/Getty

About halfway through rush hour, there were already more than 1,000 people in custody. The police had planned to bring most of those arrested to the holding area at the federal courthouse, which had about 50 small cells, the largest capacity in the city. The small dropoff zone outside allowed for only one load of prisoners to be taken in at a time. The buses got stuck in a monster traffic jam. The cops couldn’t discharge their suspects and return quickly to the trouble spots, so police began stashing hundreds of detainees in the middle of parks and median strips—at Mount Vernon Square and Dupont Circle—where they were penned in by National Guard troops and later by busloads of marines.

The tide had turned in favor of the cops. Especially euphoric were the hundreds of members of the riot squad, freed to go full tilt with all their gear and tactics. They were grabbing anyone they could see blocking roads or fleeing the scene. But that could get them only so far. Many Mayday protesters who used mobile tactics had melted into the city. In addition, there were likely thousands of others in town who hadn’t done anything illegal yet. But during the evening rush hour, or later in the week, they might. As long as we’re sweeping the streets clean of these folks, why not get them all?

Police began cruising the streets for likely suspects. The only way to pick them out was by their appearance. An officer near the Mall at 14th Street gave his underlings the order to “arrest anyone that looks like a demonstrator,” not realizing, or not caring, that he was within earshot of a reporter for the Christian Science Monitor. Another journalist, for the Los Angeles Times, observed people being rounded up as police took note of their clothes, the length of their hair, and the political buttons they wore.

It was payback time at the universities. At the George Washington campus, club-wielding police chased protesters who were seeking refuge. The cops pursued them right through the entrance to the law school building and through the hallways. They arrested a law professor who was wearing an armband identifying him as a legal observer. At the university’s hospital, two dozen people who’d been treated at the emergency room for tear-gas inhalation and minor injuries, some of whom had nothing to do with Mayday, were waiting outside for rides home. The police busted all of them, ignoring the protests of doctors and nurses. One of the college’s physical education instructors was dragged off the steps of his office building. In Georgetown, police swept through the streets, arresting kids for any offense they could gin up, such as jaywalking. Young people ran onto the Georgetown campus from the Canal Road entrance with scooter police at their heels. The cops hurled tear-gas bombs against the walls of the Copley Hall dormitory.

Other parts of town also became roundup sites. A teacher’s aide for deaf students was busted on her way to work in Dupont Circle. A lawyer studying at an institute nearby stopped to help a victim of clubbing; police grabbed him by the neck and loaded him on the bus.

Wally McNamee/Corbis/Getty

Caught in the arrests were tourists and all kinds of people who happened to appear young or just dressed as if they were. They included future Washington personalities such as Sidney Blumenthal, a budding journalist who would write for the New Yorker and become a White House adviser to President Bill Clinton. During the citywide fracas, the civilian lawyer for the police department, Gerald Caplan, ventured from his office onto the National Mall to check things out. The tear gas burned his eyes, but he saw enough to be “shocked.” Police chasing kids all over the place, “arresting everyone in sight.” The riot cops had been told not to remove their badges, but he saw that many of them had done exactly that so their prisoners couldn’t identify them later. “They had just disobeyed orders,” Caplan recalled.

By 10:30 in the morning, more than 5,000 people were in custody. The sweeps wouldn’t end until Wilson’s police department had more than 7,000 prisoners on their hands. Many, perhaps most, of the prisoners had been part of the traffic blockade. But thousands had not. Loaded onto the buses, they asked what crime they had committed. Police sardonically answered things like “walking on the sidewalk” or never answered at all. In at least one detention bus, the driver hit the brakes whenever he spotted a young man with long hair, and sent the cops out to force him aboard.

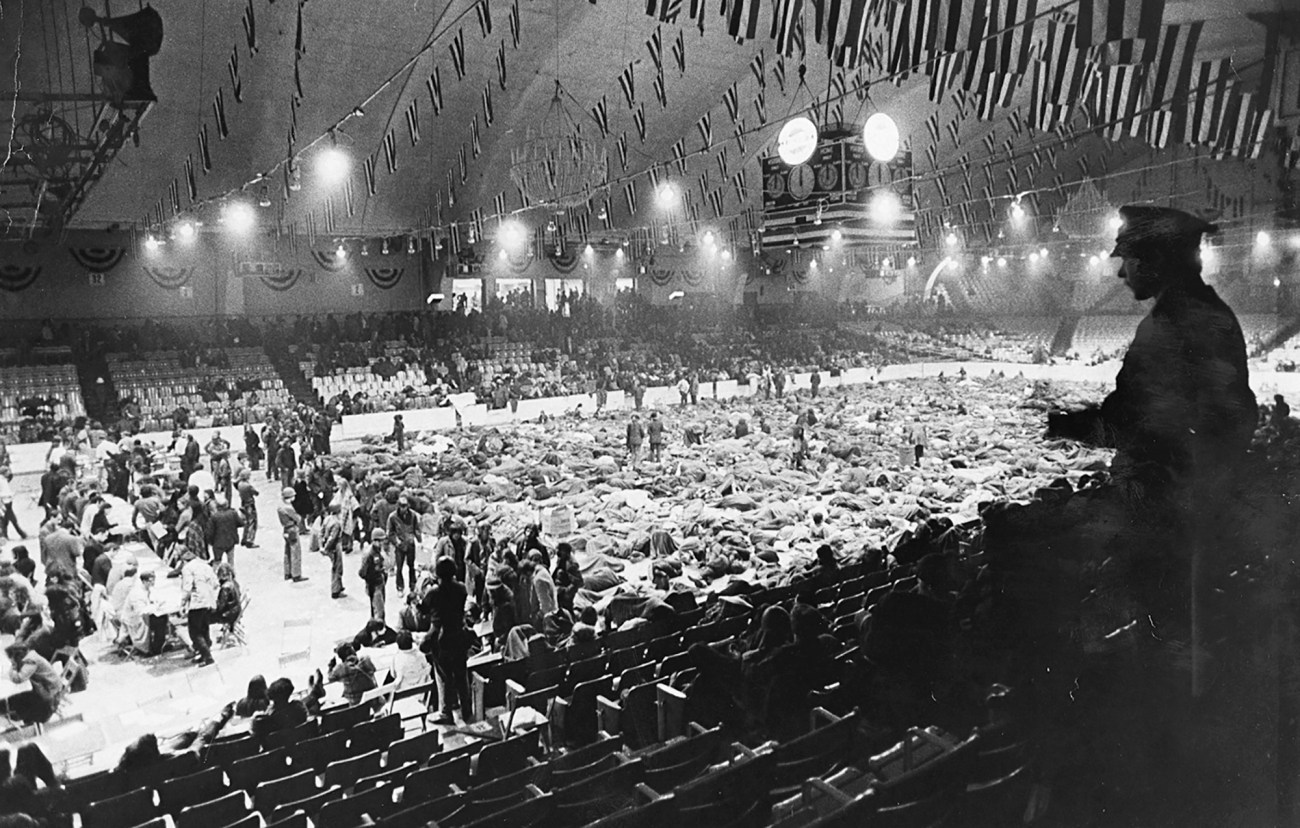

Inside the US courthouse, the cells filled up to capacity. Then the police cleared the exercise yard at the DC city jail to contain more prisoners. That wasn’t nearly enough. The police commandeered a football practice field near the multipurpose stadium recently named for the assassinated Robert F. Kennedy. Nothing but a stretch of grass and dirt surrounded by an 8-foot-tall cyclone fence, the makeshift detention camp had no provisions or shelter. The more than 2,000 detainees found some buckets and trashcans to use as toilets. The temperature remained chilly for May, only in the 40s in the morning, and a stiff and steady wind didn’t help. Few of them had been caught breaking any laws, and almost none had any paperwork filed against them. The authorities had no plans to arraign or release them anytime soon, choosing instead to keep them off the streets. Instead, when the sun went down, they were transported by bus to the Washington Coliseum, where they stretched out for the night on the oval concrete floor. Many would be there for days without contact with anyone on the outside.

Washington Post/Star Collection/DC Public Library

America’s largest act of mass civil disobedience had ended in America’s biggest mass arrest. That Monday, and at protests during the next two days, the dragnet snared a total of more than 12,000 people. They were held incommunicado for hours or days with no proper charges against them.

At first, Nixon and his team crowed about the outcome. But in the end, the justice system turned out to be far less favorable ground for them. The story of Mayday would be reversed. The administration would lose; the demonstrators would win. Public defenders and civil liberties lawyers moved into action, fighting the arrests and detentions in court and filing class action lawsuits. Eventually, judges declared virtually all the Mayday arrests illegal and ordered the government to pay millions of dollars in compensation.

As legal challenges mounted, the White House denied responsibility for the mass arrests, directing Chief Wilson to take all the responsibility, which he did. “I wish to emphasize the fact that I made all tactical decisions relating to the recent disorders,” the chief told reporters, prompting Nixon’s aides to marvel that Wilson “programs beautifully.”

Many observers suspected Nixon and his men were pulling the strings but couldn’t prove it. Nixon’s own accounts, caught on tape, have remained unreported until now. They leave no doubt that the responsibility for the Mayday dragnet can be laid at the doorstep of the Oval Office.

The president discussed it several times, stating it perhaps most clearly to a group of conservative lawmakers he invited to a meeting at the White House in mid-May. Referring to the war councils held at the Justice Department, he said the plan for dealing with the demonstrators had been fully worked out in advance. “Now, you can get into a lot of fine arguments as to whether or not individuals should be arrested under those circumstances,” said the president, but he vowed not to “run away from it just because some people in the press don’t like it.”

He added, “The point is, I had the responsibility…I approved this plan.”

A couple of weeks later, he talked it over with his chief of staff: “We arrested a hell of a lot of people. In a strictly legal sense, it was not legal.”

“That’s right,” Haldeman replied.

“But we had to do it. Now that’s all there is to it. And we’ll do it again. Because keeping this government going is more important than screwing around. Because nobody was thrown in the can, nobody was kept in the can, they were all released. So what are they squealing about?”

Nixon concluded, “And don’t worry about this little technical legal question.”

This article is adapted from Mayday 1971: A White House at War, a Revolt in the Streets, and the Untold History of America’s Biggest Mass Arrest (published Tuesday by Houghton Mifflin Harcourt).